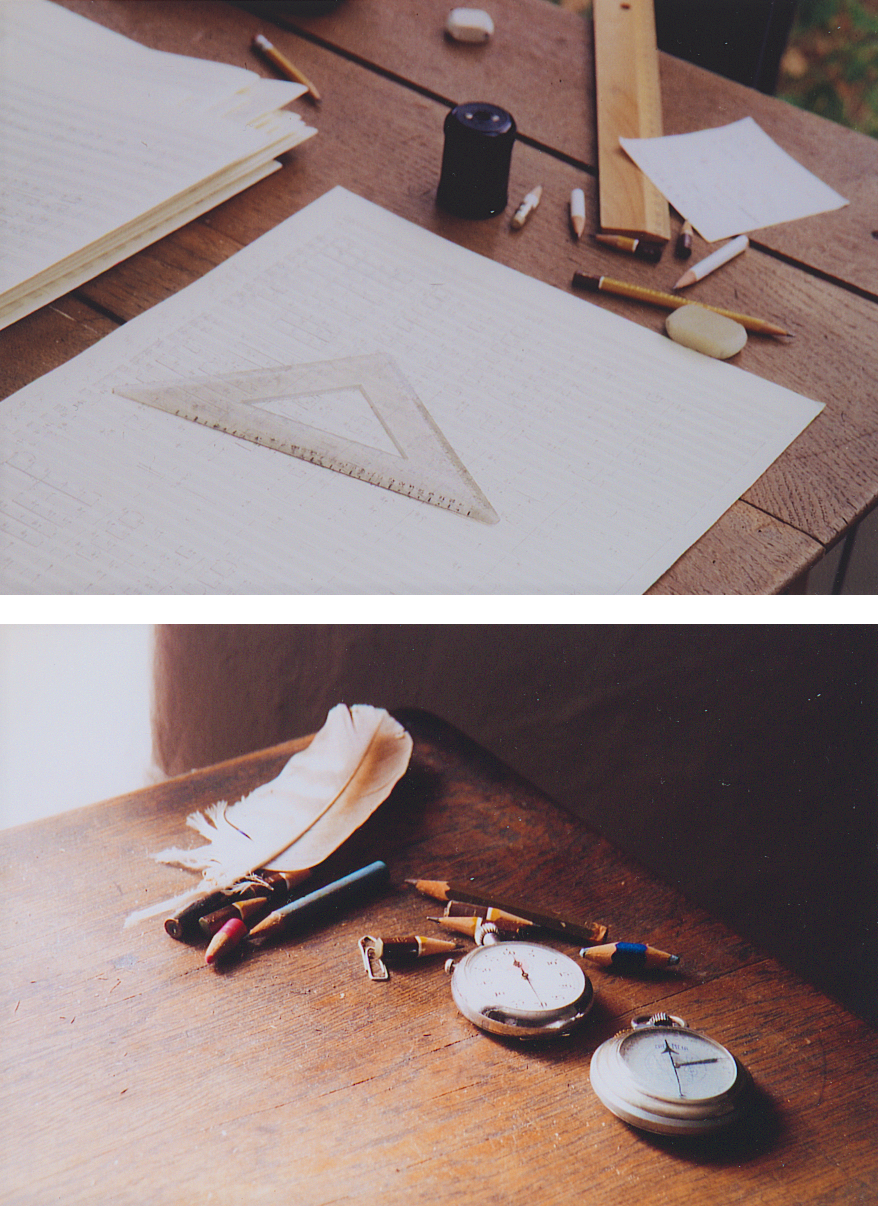

The Composer

Cerha while composing

Friedrich Cerha primarily composed in two places: A glasshouse overgrown with plants in Maria Langegg and the composing room of his Vienna apartment (where this portrait was taken).

Photo: Hertha Hurnaus.

A Short History of Composer Friedrich Cerha

After 1945, Cerha sought out new musical arenas, preferably those that were little known, with the curiosity of a researcher. He absorbed everything he was not yet familiar with—including music that was only a few decades old but had been blacklisted during the war. He was inspired by French Impressionism, Slavic music, the Neoclassical, and soon by 12-tone works from the Vienna School, which was rarely played at the time. Cerha took home scores from the academy library by the suitcase, studying and playing them—often in a duo with his companions Hanns Kann, Gerhard Rühm, and others. Happy to experiment, these Viennese composers gradually formed a loose-knit group “who sympathised with the young artists and writers of the Art Club.” Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 218 Though people were leery of anything that suggested the appearance of a strict collective (after all, the abolition of individual freedoms had led to immense catastrophe just a few years earlier), common ground did emerge. An independent musical language turned against the prevailing academic style. The keyword was reduction: A kind of Austrian minimalism was created through the conscious renunciation of the process of developing using themes and motifs. Cerha’s Buch von der Minne (1946–1964), a gigantic song cycle, is particularly influenced by such ideas.

At the same time, Cerha’s great sensitivity allowed him to discover new in the old. He was particularly interested in the early Baroque, a time in which an unprecedented, deeply human expression was revealed through art and music. Works such as Aria und Fuge for eight wind instruments (1946) and Ricercar, Toccata und Passacaglia (1951–1952) conjure up centuries-old genres with their names, yet they are addressed from a contemporary point of view. Cerha remained a mediator between the old and the new his entire life, not least by building bridges through the concert series “Wege in unsere Zeit” (Paths to Our Time).

Darmstadt in the 1950s was a place where composers grappled with the future of music . “There was sense of setting sail for new musical worlds,” says Cerha, “a feverishly tense atmosphere in which new possibilities for structuring and organising music were discussed in heated debate from breakfast until late in the night, that was an exciting experience for everyone involved.”Cerha, “Viele Anregungen vom Rande. Stimmung des Aufbruchs in neue Welten”, in: Rudolf Stephan et al, (ed.): Von Kranichstein zur Gegenwart. 50 Jahre Darmstädter Ferienkurse. 1946-1996, Stuttgart 1996, S. 188-191, hier S. 188 The trends of that era can be found in Cerha’s compositions from the time; ideas of a formal openness, for example, yet framed by the catchphrase “aleatoric”, emerged in the 1959 ensemble piece Enjambements, one of the last works of the Darmstadt period. That same year, Cerha turned to completely new, undreamed-of worlds of sound, for which he “clearly no longer needed additional external stimuli”.Cerha, “Viele Anregungen vom Rande. Stimmung des Aufbruchs in neue Welten”, in: Rudolf Stephan et al, (ed.): Von Kranichstein zur Gegenwart. 50 Jahre Darmstädter Ferienkurse. 1946-1996, Stuttgart 1996, pp. 188–191, here p. 191

After these phases focussing on experimentation, Cerha again set sail for new shores in the 1960s. His attention to detail in his sound compositions, and their tendency to create a monolithic mass, aroused an interest in the opposite: transparency, flexibility, and tradition. Cerha expressed these longings in Exercises (1962–1967), all without overlooking his previous experiences as a composer. Within a sound system made up of different levels that were mutually influential, he integrated everything that he had previously worked on: serial orders, overgrown sound structures, motif variations and mixtures—he even invented his own artificial language for the piece. His compositional ideas were largely nourished by cybernetics, a young universal science dealing with the equilibrium of systems and their disturbances. In Fasce, Cerha had already implemented ideas from this field to create dramatic processes, but within an unadulterated world of sound. Cerha now stopped limiting himself to a certain material, to one exclusive way of writing music. In the late 1960s, pieces emerged that almost seemed to play with a forced versatility: the Catalog des objets trouvés, for example, or the first of his three Langegger Nachtmusiken (both 1969). In these works, foreign music enters the listener’s ear; citations and allusions subtly evoke the music of the past. This confrontation with tradition seemed inevitable, the only way to work through the impasse of the avant-garde.

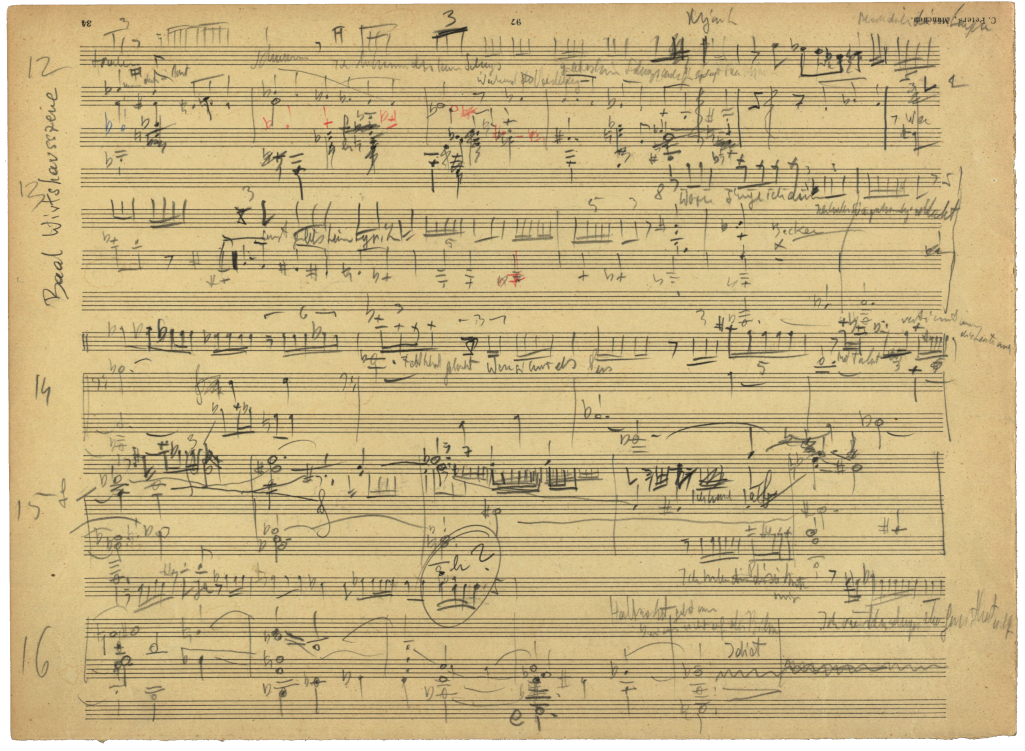

Cerha composing in Maria Langegg

Photo: Hertha Hurnaus

In the new millennium, many aspects of Cerha’s work have seemed to reappear, but in a different form. More than ever, highly dissimilar works are created in parallel. Monumental orchestral pieces like Hymnus (2000), Nacht (2013), and Eine blassblaue Vision (2013–2014) tie into his early sound compositions. Contrasts between the collective and the individual become reality in filigree frameworks such as Musik für Posaune und Streichquartett (2004–2005), as well as on large scales, such as the virtuoso Konzert für Schlagzeug und Orchester (2007–2008) composed for Martin Grubinger. Cerha counteracts his academic compositional style with works that celebrate small and poetic forms: Momente (2005), Instants (2006–2008), and Kurzzeit (2016–2017) all express the “joy of a spontaneous idea, a flash of intuition”.Cerha, text for Momente, AdZ, 000T0137/2.

The reason for the pronounced diversity of his work, explains Cerha, “is that at several stages of development, [I] followed different evolutionary strands, each starting from a single point, that then diverged.” Joachim Diederichs: Friedrich Cerha. Werkeinführungen, Quellen, Dokumente, Vienna 2018, p. 126 His oeuvre resembles—to use one of his most emblematic titles—a network.