Zehn Rubaijat

des Omar Chajjam

Of Wine and Honey

Zweites Streichquartett

Phantasiestück in C.’s Manier

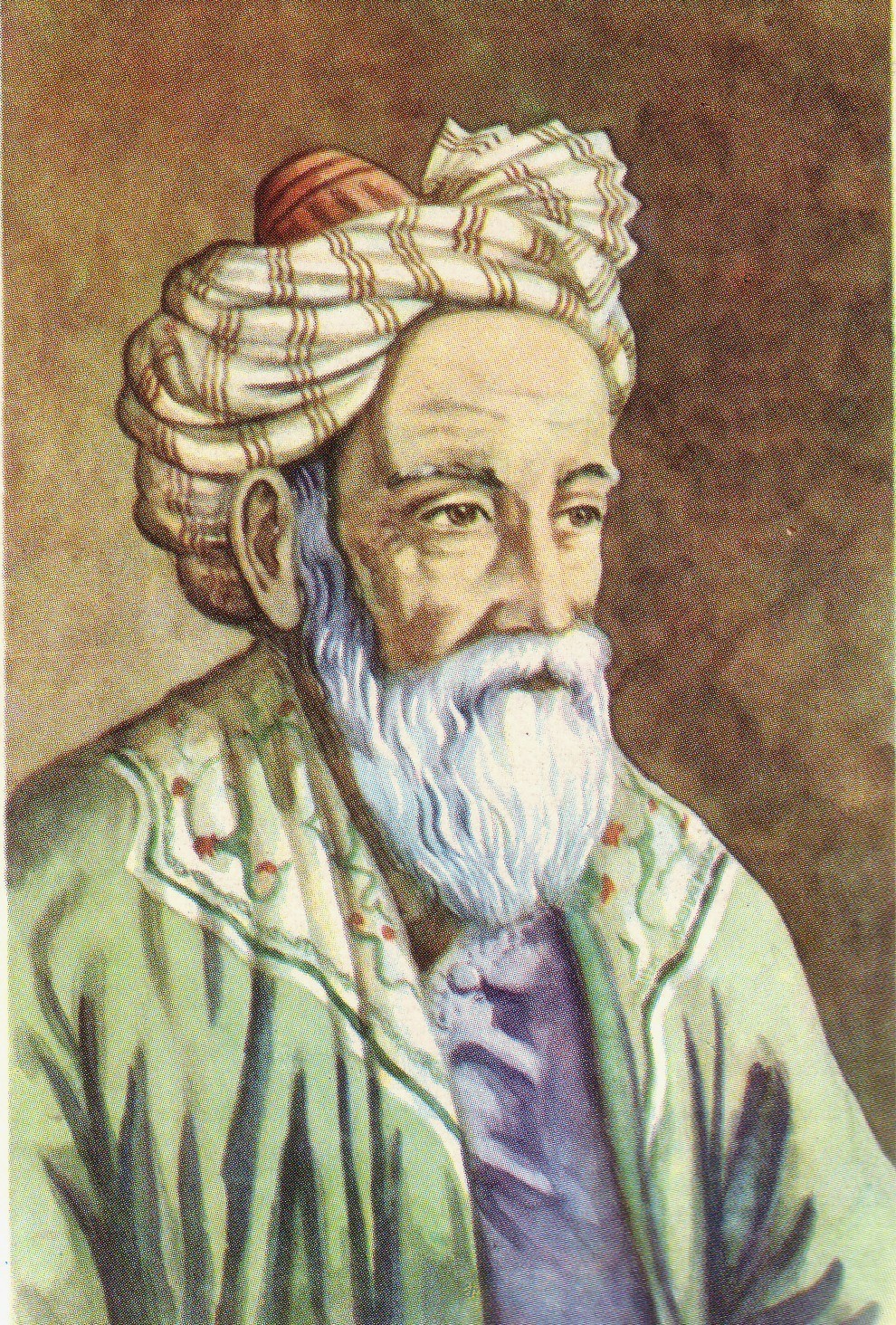

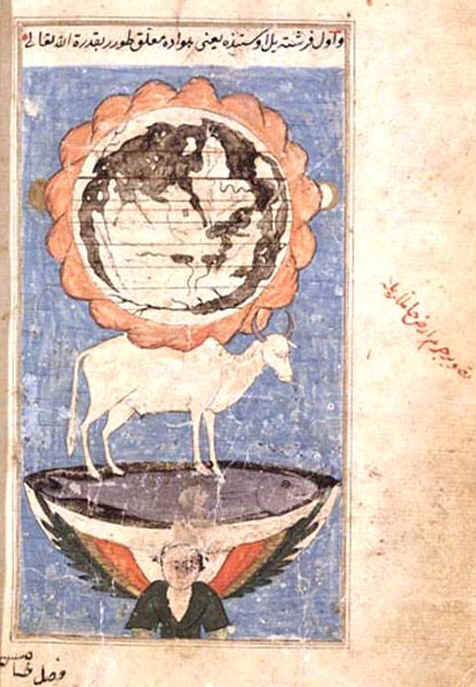

Edmund Dulac, Rubáiyát illustration

from: Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, London: Hodder & Stoughton 1909

In Dulac’s illustration, the figure of the Oriental scholar in a sensual night scene is also quite apt for poet Omar Khayyam’s character. His poetry is an intellectually refined nod to the pleasures of this earthly life.

Source: Crossett Library/Flickr

Magical worlds open up behind many a book cover.

Source: Crossett Library / Flickr

The illustrations by Franco-British graphic artist Edmund Dulac, who became one of the leading book illustrators of the early twentieth century, are like scenes from One Thousand and One Nights. The narrative images are no coincidence, as Dulac also illustrated fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. Here, however, the illustrations were not created for a book of fairy tales, but for an edition of Omar Khayyām’s Rubaiyat published in 1909—quatrains written in the eleventh and twelfth centuries attributed to the Persian polymath. Some of these form the basis for Friedrich Cerha’s Zehn Rubajjat des Omar Chajjam.

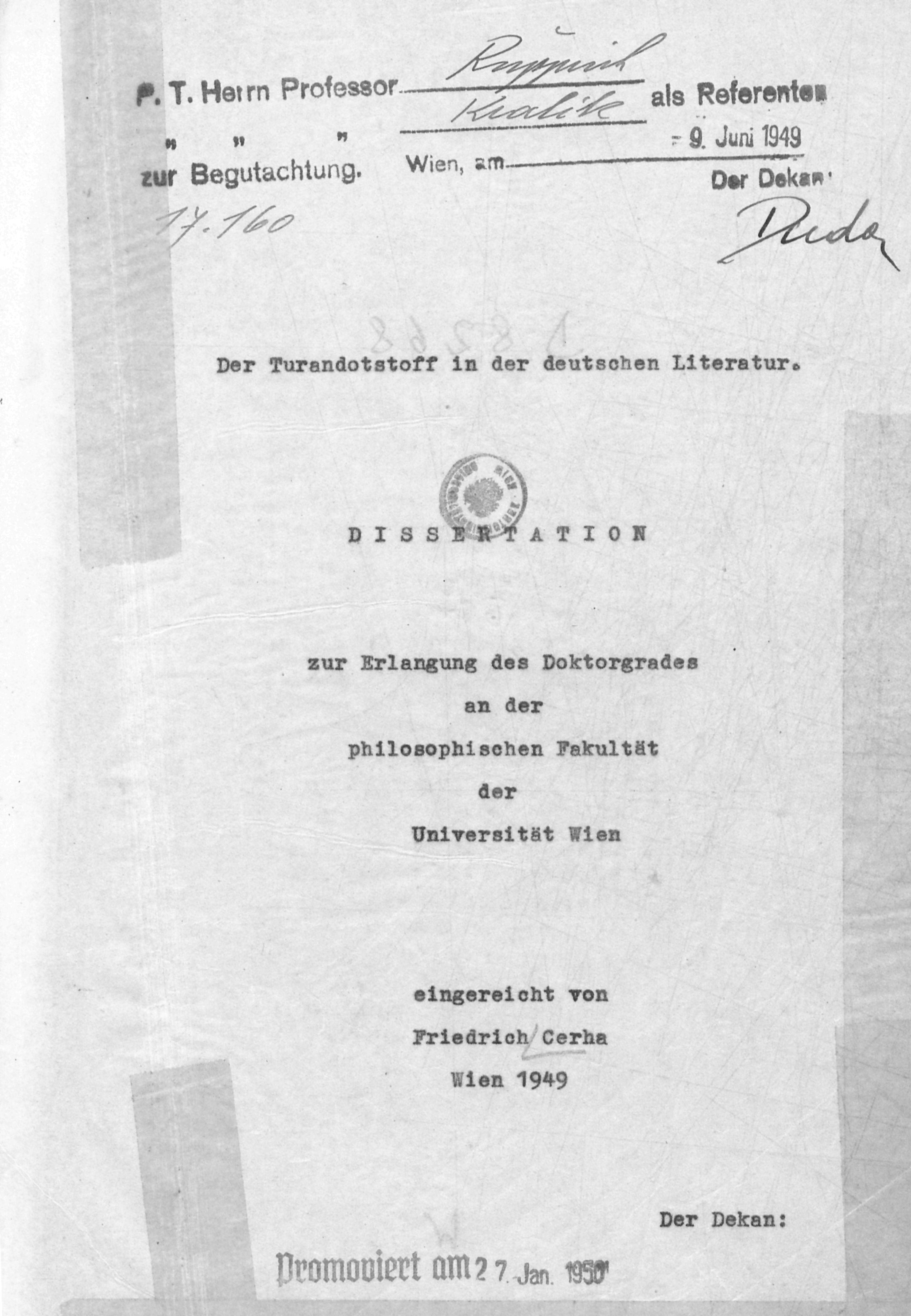

Außenansicht

From an early age, Cerha had an intense level of contact with Persian cultural history. As a student at the University of Vienna in the late 1940s, he decided to write a doctoral thesis on the mythology surrounding Chinese princess Turandot, whose origins lie in Persian literature.

In the course of his research, Cerha came across a volume of poems by Omar Khayyām, often also called Omar the Tentmaker (most likely the profession of his father, Ibrahim). The poems were centuries old: Omar was born in 1048 in Nishapur, a flourishing intellectual and cultural centre of Persia (today Iran), and one of the largest metropolises of the time. During Omar Khayyām’s lifetime, the world’s largest university libraries were located there and in Baghdad.

Considering the environment, it is not surprising that Omar grew up to be one of the greatest scholars of his time. His most important discoveries include ground-breaking mathematic innovations—solving, for example, cubic equations—the construction of an observatory, and the creation of a solar calendar at the behest of Sultan Malik Schah I. The Arabic lunar year and the Persian solar year were both replaced in 1079 based upon this work. In addition to these numerous significant scientific achievements, it is above all his poetry that Omar Khayyām is remembered for today. Around 600 short poems called “Rubā’īyāt” (or Rubaiyat) are among the greatest cultural assets of the Middle East. Translated into English by Edward Fitzgerald in the mid-nineteenth century, they helped fuel the Orientalism of the fin de siècle. Countless versions of the Rubaiyat have been published since, one of which came to Cerha’s attention, inspiring him to write choral pieces.

Portraits of Omar Khayyām

Omar Khayyām Mausoleum, Nishapur, Iran

Brücke

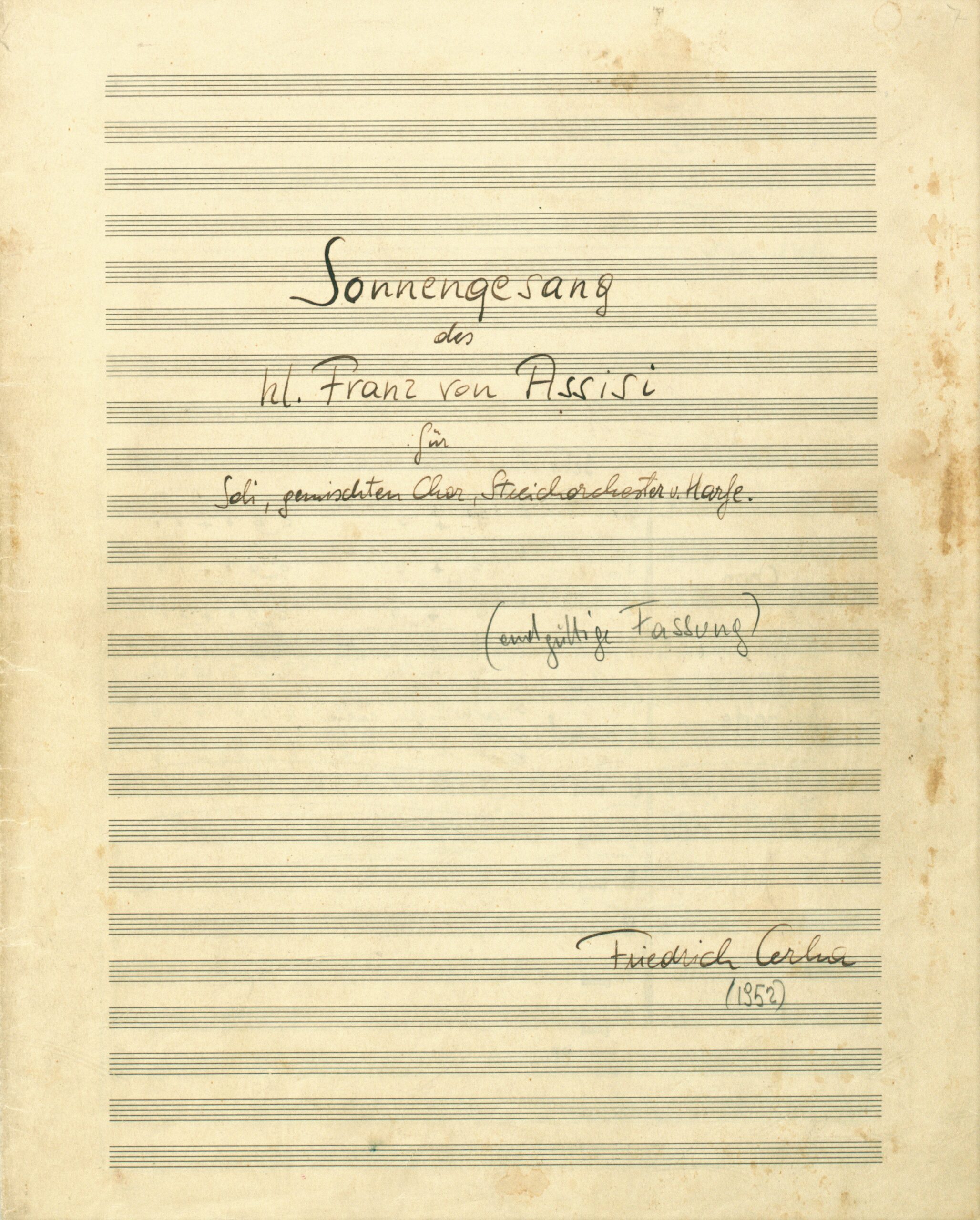

Cerha’s decision to use a choral treatment of the Rubaiyat is not entirely atypical for the late 1940s and early 1950s. In the same period, he wrote the Sonnengesang des hl. Franz von Assisi and the cantata An die Herrscher der Welt, two more choral works underpinned by a religious subject matter.

The Rubaiyat were placed in a spiritual context during Omar’s lifetime, and while one could easily assume that Cerha was drawn to this aspect as a young composer, the opposite is actually true: It was the poems’ polemic against a lifestyle bound by faith that attracted Cerha:

“In the course of my occupation with Persian literature […] I came across the Omar Khayyam’s early twelfth-century Rubaiyat and was fascinated by the satirical sharpness, pointedness, and expressionistic approach to life behind them, which allowed them to remain highly topical. Their content was seen as religious at the time of their writing—something which looks like camouflage to us today.”

Friedrich Cerha

Begleittext zu den Zehn Rubaijat, Archiv der Zeitgenossen, Krems, Signatur 000T0029, S. 2.

In fact, Omar’s writings contain a secular, almost serene sophistication, which does not quite align with the doctrines and dogmas of religion. In the present day, the lyric “I”, often seeking pleasure and bewitched by the sensual stimuli of the everyday world would likely be labelled hedonistic. A frequently recurring symbol is wine—the Rubaiyat could almost be characterised as drinking songs. In addition to the plea for enjoyment, a protest against Islam’s ban on wine can also be read between the lines, adding a layer of political weight. Criticism of Islam is not spared in other places either, for example, questioning the Koran’s promises of Huris—virgins waiting in paradise—as in the following (freely translated) Rubai:

You say there will be wine flowing through your streams,

is paradise then a tavern?

You say every believer will be rewarded with two virgins,

is paradise then a brothel?

The extent to which these short poems have remained explosive today becomes clear from the fact that, in 2013, an Istanbul court sentenced Turkish pianist and composer Fazil Say to ten months in prison for posting the above Rubai on Twitter. Omar was also criticised for his poetry during his lifetime, above all by the Sufis, a branch of Islam advocating an ascetic lifestyle.

In a certain sense, Cerha’s selection of the writings is almost a political act, although his interest lay not so much in criticising Islam itself (a culture he valued), but rather in the act of resistance and in highlighting a commitment to life on earth. The specific writings he chose place particular emphasis on transience, sensual enjoyment, scepticism of doctrines, and criticism of power.

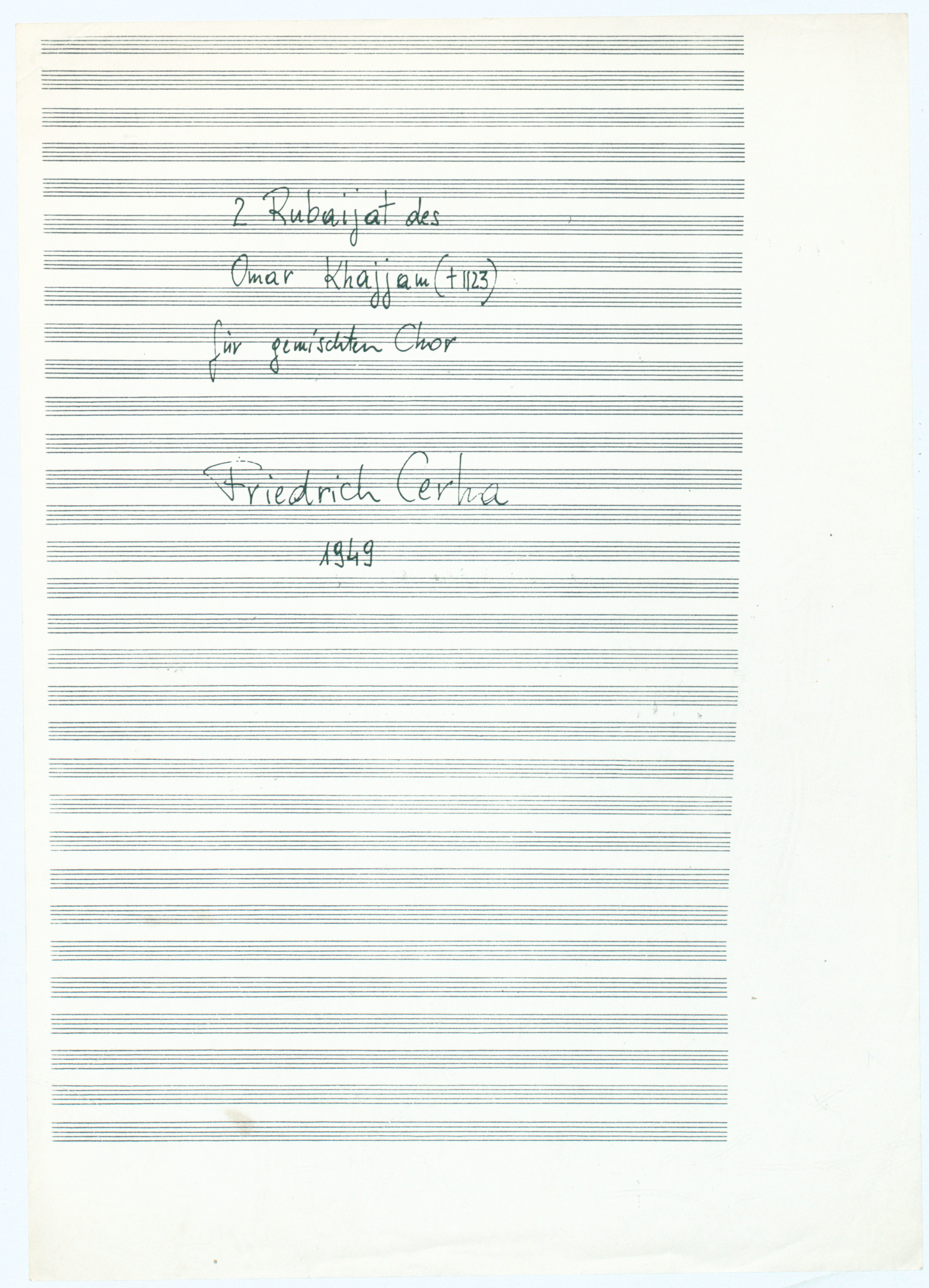

Cerha set two Rubaiyat to music in 1949 and developed a plan to write a full collection several years later. In the early 1950s, he combined the individual pieces he gradually composed into bundles—evidenced by manuscripts from the time.

Title pages of several versions of Cerha’s “Rubaijat”, 1949–1955

Innenansicht

In order to truly understand Cerha’s Rubaijat, a few notes on the tradition and poetry of the short texts are essential. Omar’s Rubaiyat are often referred to in German translations as “aphorisms”, as is the case in the 1922 edition in Cerha’s private library. This translation emphasises that the Rubaiyat were and are predominantly perceived as adages with a certain punch line. The rubaiyat also all follow a specific form. The Arabic word Rubāʿī means “quatrain”—a form of poetry that was particularly popular in Persian literature during the ninth to twelfth centuries. In keeping with this, the rubaiyat classically consist of four verses with a distinctive rhyme scheme. Of the four verses, the first, second, and fourth usually rhyme, while the third deviates to take things in a different direction. A conclusion or summary is drawn in the final verse.

Exceptions, however, confirm the rule: There are also rubaiyat in which all the verses rhyme.

The economical nature of the poems provides fertile ground for musicalisation: Cerha’s compositions also are characterised by brevity, expressiveness, and tight lyric-tone interactions. Each rubai stands on its own, as there was originally no intention to bring the pieces together to create a unified message. Friends of Omar used to collect and copy the scholar’s quatrains for preservation, meaning that in some cases the true authorship remains questionable. Only a few out of this loose collection of material have been singled out for translation into other languages. However, the bundles of rubaiyat from the 1950s have a noticeable tendency to create a certain drama and conclusion—i.e., to relate the pieces to one another, as can be seen in the final collection of ten pieces. Cyclical unity is achieved by the calm and meditative qualities of the first and last pieces. The chosen poems are also existential, asking questions about the meaning of life. Between these framework pieces is space for lighter, even humorous compositions. A list of all pieces in the final arrangement can be found below:

Als Du das Leben schufst, schufst Du das Sterben:

Uns, Deine Werke, weih’st Du dem Verderben.

Wenn schlecht Dein Werk war, sprich, wen trifft die Schuld

Und war es gut, warum schlägst Du ’s in Scherben?

Ein Vogel saß einst auf dem Wall von Tûs,

Vor ihm der Schädel Königs Kaykawûs.

Und klagte immerfort: Affssûss, Affssûss!

Wo bleibt der Glocken und der Pauken Gruß?

Ein Stier ist, der drunten auf seinem Horne die Erde hält

Ein anderer Stier strahlt hell dort oben am Himmelszelt.

Doch an die Menge von Eseln denk ich mit Grausen,

Die zwischen den beiden Stieren hausen!

Was heut hierher mich trieb? Ich sag es unverhohlen:

Ich hatt’ in der Moschee einen Betteppich gestohlen,

Der ist jetzt alt und schlecht, drum kam – ein seltner Gast –

Ich heute wieder her, einen neuen mir zu holen.

Von Wein und vom Honig im Paradies

Sprecht ihr und von Huris, den schönen

Und was der Prophet uns da drüben verhieß,

Das wollt ihr auf Erden verpönen?

Du zerbrachst mir, Herr, meinen Krug mit dem schönsten Wein.

Zum trunkenen Glück verschloss mir die Türe Dein Spott.

In den Staub rot gossest Du selbst den lieben Wein

Mir dankbar Durstigem – warst Du betrunken, Gott?

Die Weisen erzählen ein Märchen

Vor Schlafengehen

Uns unartigen Kindern

Und fallen selber in Schlaf

Dem Töpfer sah einst im Basar ich zu,

Wie er den Lehm zerstampfte ohne Ruh.

Da hört’ ich, wie der Lehm ihn leise bat:

„Nur sachte, Bruder, einst war ich wie du.“

Zwei oder drei Tröpfe, an Geiste blind,

Sind ’s die auf Erden als Herrscher walten.

Lass du sie schalten. Für Ketzer halten

Sie alle, die keine Esel sind.

All unser Leben und Streben – was taugt ’s?

All unser Wirken und Weben – wer braucht ’s?

Im großen Schicksalsofen verbrennt

So vieles Edle und Gute – wo raucht ’s?

Here, a closer look at three of Cerha’s Rubaijat.

Arnold Schönberg Chor, Ltg. Erwin Ortner

The first Rubai is the most thoughtful of the ten pieces—a meaningful entrance if one considers that the other poems usually make the listener smile. With this decision to place reflections of mortality at the very beginning, Cerha also puts the subsequent choral pieces into perspective, placing them under the umbrella of an existential questioning of life.

Omar’s is divided into two halves: In the first, the focus is on human mortality, while the second poses questions to the Creator, which remain unanswered. This Rubai is a good example of the typical Persian rhyme scheme: Only the third line does not rhyme with the first word sterben (to die), instead bringing in a different thought.

Cerha’s musical setting is primarily based on this rhyme scheme, but also highlights the poem in a very special way. The music is closely linked to Omar’s lines. The piece begins with a step-by-step building up of voices: Over the first few bars, the solo tenor is followed the alto, then the soprano, and finally the bass. This choral build-up from the centre clearly follows the emerging life of which the poem speaks. At the word sterben, which the different voices (like individuals) reach at different times, a marked clouding is noticeable, created especially by the outer voices leading the melody downwards, mostly in semitone steps. This creative element draws from the old rhetorical passus duriusculus (the hard walk) that has been used to represent pain and death since the seventeenth century.

After the first line glides gently into a closing F-major chord, Cerha begins a second build-up, this time with more urgency, reflecting the self-examination of the lyrical speakers of the poem (Uns, deine Werke). The three upper voices are staggered in the beginning yet within a single measure, while the notes become shorter and the movement thus has a more agitated feel. The line clearly leads to the word Verderben, to decay: The soprano reaches a top note with the word, reinforced by the low note of the bass. The line again closes with a major chord, this time with an E-flat [D-sharp] root.

The driving densification and growing tension are brought to a climax in the third line, paralleled in the lyrics by the first question, almost an accusation to the Creator. Dissonant friction increases in parallel with the declaration of the poem—as do volume and articulatory stridency. The ambitus splays apart, leading the marginal voices into extreme areas in parts, ending in a chord that stretches across almost three-and-a-half octaves on the last word of the line, Schuld (guilt). Unlike before, all voices reach the last word at the same time, giving it special weight. The interesting thing about the last chord is that it contains both major chords of the previous line endings—soprano and tenor together form an E-flat major chord, and the alto makes the F-major sound with a slight variation. By continuing the tenor, the chord reaches eight voices at its end.

The final line of the rubai is completely different. It does not continue the pressing complaint, instead returning to the emotion of the beginning: The choir voices return at a lower, more relaxed register, cease to make great leaps, and create longer arcs. The connecting melody lets the word warum emerge from the delicate vocal network with particular frequency. The piece ends with extreme finesse and glory on a dark and mysterious four-note chord with a hidden C-minor chord. Life is shattered.

Arnold Schönberg Chor, Ltg. Erwin Ortner

The earth is on water, the water on rock, the rock on the back of an ox, the ox on a heap of sand, the sand on the back of a fish, the fish on the still wind, which is surrounded by darkness; the darkness rests on the damp earth reached by the knowledge of creatures.

al-Muqaddasī

Cf. translation in: Hans Daiber, Aetius Arabus. Die Vorsokratiker in arabischer Überlieferung (Veröffentlichungen der orientalischen Kommission, Vol. 33), Wiesbaden 1980, p. 448

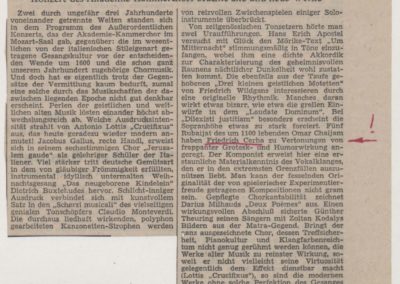

The legend of the prehistoric fish named Bahamūt, which carries the ox that bears the earth, has many variation in mythology. An old illustration made after Omar’s time can be found in the cosmology of Zakariya al-Qazwini.

The ironic coding of the tenor voice as that of a donkey continues after the solo. The tenors come together in a free melody that reproduces the text, entering between the bass (symbolising the earthly ox), and the female voices (the celestial ox). The two-bar patterns are articulated by the marginal voices, in turn building a bridge to an increasing implementation of Arabic rhythmic patterns, this time more reminiscent of joyful festivities or ritual music. After another interjection creates a “crowd of donkeys” through vocal imitation, the piece closes on the following dance-like note.

[1] Koran, Sura 31:19

Illustration des Bahamūt in Zakariya al-Qazwinis Kosmologie ʿAjā’ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā’ib al-mawjūdāt (deutsch: „Die Wunder des Himmels und der Erde“)

Bildquelle: Wikimedia

Arnold Schönberg Chor, Ltg. Erwin Ortner

Number 4 of the Rubaijat cycle is not only smart and humorous, it is probably the most sharp-tongued. It allows the poignant reminders of our mortality in the first Rubai, for example, to be quickly forgotten, addressing nothing existential at all (making it an exception among the pieces). The scene is that of a mosque—quite special, considering that while hints of religious topics are quite usual, specific places and institutions are rarely addressed directly. Only No. 5, Von Wein und von Honig, plays as openly with the teachings and practices of Islam by critically questioning the otherworldly promises of the prophet.

The poem describes, from a first-person perspective, a thief stealing a bed carpet from the holy walls and not re-entering the mosque until he wants to steal a new carpet. This allows the listener to infer the motives of the bigoted believer, who, untouched by the spiritual ceremonies, continues to succumb to the commission of sinful acts. A similar motif, but with a different undertone, can be found in Gustav Mahler’s song Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt, which is based on the folk poems of Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Here, a preacher speaks to the fish, who listen to him with great interest, yet quickly forget the sermon and learn no lessons nor draw any conclusions from what they have heard.

Cerha’s musical setting of the quatrain aligns itself strongly with the drama of the narrative, which is almost a crime thriller. Accordingly, the composition embodies great variety: Each line implements a different scoring technique. The first line of the rubai stands out in particular. Cerha divides the poem almost word for word into the various choral voices, creating a splintered, broken sound. A closer look at the notes reveals twelve-tone fields: The first field spans the first three bars, the second the next three. Diversity is reflected in the rhythm, which allows both sustained notes and extremely short, punctual durations to interweave. Suddenly, changing volumes appear, a sign of instability. The entire dissociation of the design elements is an indication of the serial age, when the splitting of musical components was particularly brought to the fore. However, the opening passage is not serial—it can’t be, as Cerha wrote Rubaijat prior to his first visit to the Darmstadt Summer Course for New Music.

A completely different technique prevails in the second line, with symbolic value, as it were. The tale of the earlier theft is represented by successive imitations of the motif by the voices. The tonal sequence B-A-C-H is prominent here, which can in a way be considered Johann Sebastian Bach’s musical signature, a noticeable allusion to the grand master of polyphony. This line of the rubai comes right after “What drove me here today …”, and as such can be interpreted as Cerha making a statement: As a composer, he followed the trail of Bach.

The third line proves that the tonal sequence was not just a simple coincidence. Almost as if speaking, the alto tells of the “old” carpet, while the male voices beneath him form a literal carpet of sound woven from long notes. The tones of the tenor correspond to a different pitch of the B-A-C-H sequence. Concealed irony cannot be denied, if one considers that Cerha allegedly insinuated that the teachings of the baroque master were antiquated and dusty. The criticism, hardly meant as serious, corresponds in any case to the cheeky and teasing message of the text.

The renewed vocal imitations, describing the walk into the mosque, seem extremely mischievous in this light. They begin hesitantly and are suddenly interrupted by two solo interludes, by the tenor and the alto. These sing of the new carpet, their high position and tone of voice reminiscent of the calls to prayer (adan) heard so often in the Islamic world. Cerha integrates the sound of the mosque itself into his setting, before renewed vocal imitations casually resolve the brazen theft.