The Networker

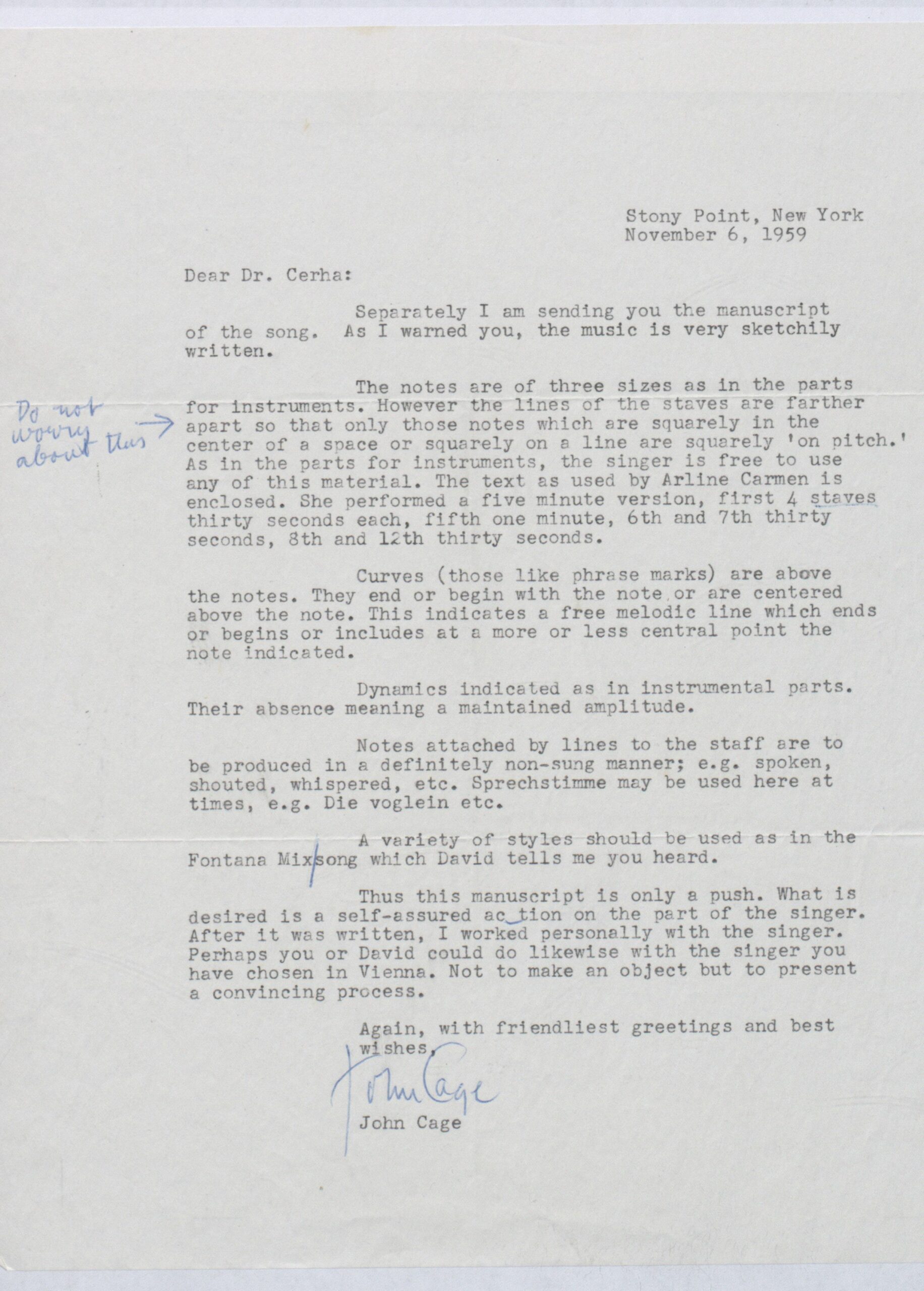

Cerha with Pierre Boulez, Salzburg 1996

Pierre Boulez was one of Cerha’s closest allies among his circle of colleagues. The two were not only composers, they were also active conductors and performed each other’s works. The photo shows them getting ready for a concert of Cerha’s orchestral piece Impulse in the Großer Festspielhaus Salzburg, conducted by Boulez.

Photo: Marion Kalter

In the age of social networking, establishing good connections with other people, both like-minded individuals and casual acquaintances, is more relevant than ever before. Since the digital revolution, the word network has become a common way to describe the benefits of having a certain ease in one’s personal relationships. In order for someone to strengthen their ideas, make them visible, and ensure they become reality, it is necessary to know people with similar interests. Aside from economic implications, networking also enables dynamic creativity—especially in the field of art. Today, the romanticised notion of the isolated artist, working in a quiet little room, a stranger to the world, seems a bit dusty. On the other hand, many of the more recent trends throughout art and music history would hardly have been conceivable without public discourse, the lively exchange of ideas, and the formation of groups.

Friedrich Cerha’s relationship to networking cannot be described without acknowledging a sense of ambivalence. On the one hand, he is an individualist, someone who does not feel he belongs to any school or fashionable trend, someone who chooses his own sometimes daring paths. On the other hand, he is someone with a broad range of interests, someone with eyes wide open and with a broad view of world events and those who make them happen. Cerha, the networker, can be found somewhere within this range between personal independence and openness:

Cerha, the—sometimes—self-isolator. Is this why he worked for years on Brecht’s Baal, discovering a kindred spirit in parts of him? That, too, is only true to a certain degree. It was the topicality of Baal that excited Cerha so, the fact that an organised society can offer up reasonable living conditions that certain individuals neither can nor want to accept. The alternative is to escape, an internal migration, ultimately a path leading to self-destruction. Cerha is realist enough, in spite of his own defensive measures of putting up a shield, to not go down that path, or even want to. Curiosity led him forward.

Lothar Knessl

“Versuch, sich Friedrich Cerha zu nähern”, in: Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 14 f.

Early Infrastructures

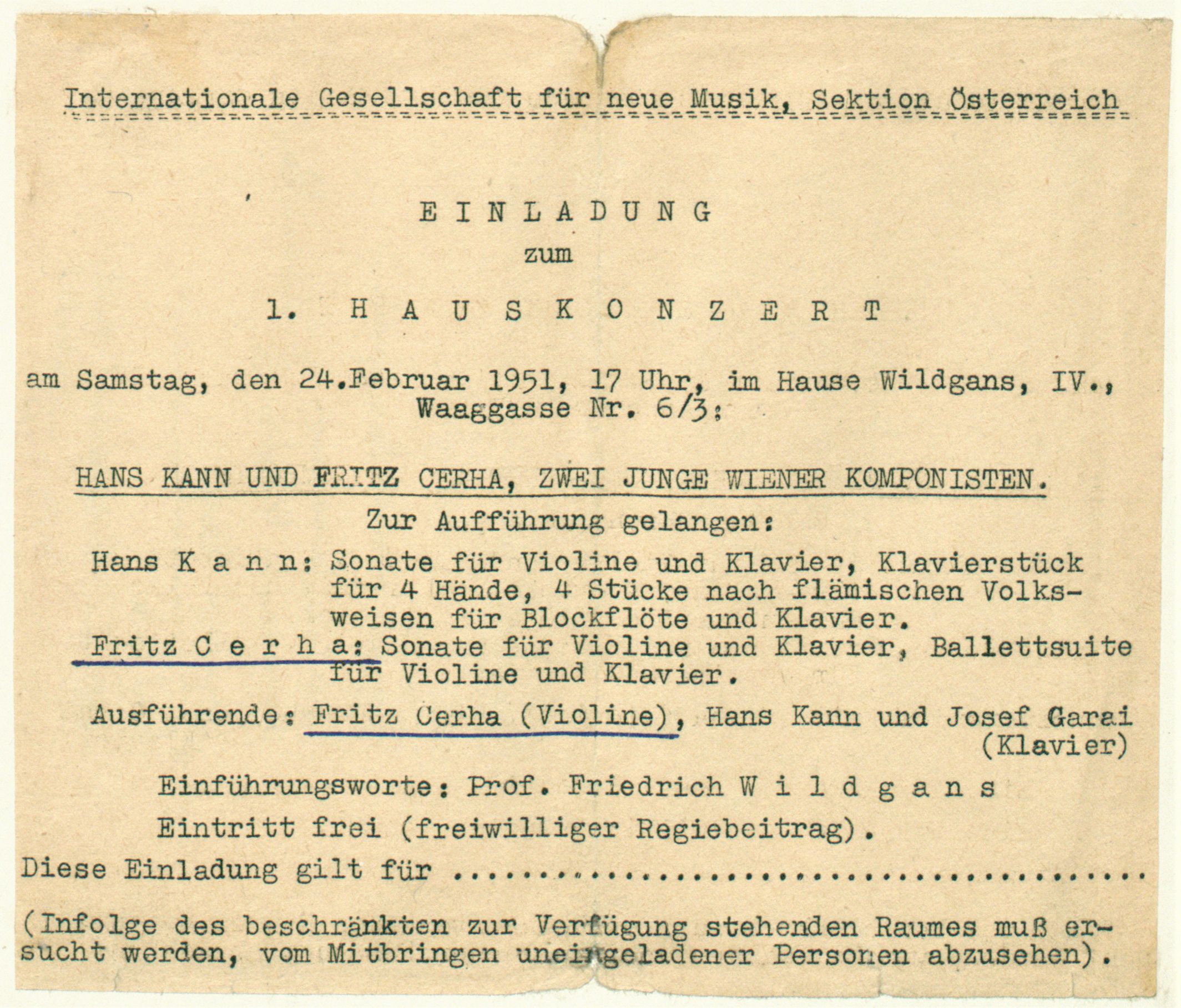

In the early 1950s, Polnauer helped open another door for Cerha: to the International Society for Contemporary Music—the Gesellschaft für Neue Musik, or IGNM for short—a descendant of the “Society for Private Musical Performances” founded by Schönberg in 1922. In the post-war period, the Austrian section of the IGNM promoted all types of contemporary music. At the same time, it was deeply influenced by the “mentality of the Viennese School”Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 45. Although neoclassical or minimalist styles of expression were not excluded from the programmes, they were regarded with some scepticism. Maintaining independence from the commercial cultural scene was highly important for the IGNM, a stance which caused a degree of isolation. Public visibility suffered as a consequence, and concerts were often moderately to poorly attended. The scene itself remained quite small, and efforts to grow it were limited, probably also in order to maintain the ability to fulfil the members’ needs.See Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 43 Early core members included composers Friedrich Wildgans and Hans Erich Apostel, singer Ilona Steingruber, and musicologist Erwin Ratz. Cerha became acquainted with them after being invited to IGNM concerts by Polnauer. His colleagues soon accepted him onto the society’s board, later electing him to position of vice president and, in 1968, president. The financially weak yet ambitious society was only able to put on large concerts “with the help of the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation”.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 51 For this reason, private concerts were held regularly, often at Friedrich Wildgans’s home on Waaggasse, not far from Belvedere Palace, usually for about 40 listeners. On 24 February 1951, this was the site of Cerha’s first musical portrait concert; as a young composer, he was presented alongside his friend Hans Kann.

“Invitation to a home concert”, IGNM Austria, 24 February 1951, AdZ, KRIT0007/12

The house on Waaggasse became a central venue for Neue Musik in Vienna. This withdrawal into the private sphere went hand in hand with the displacement of Modernism from public concert halls. For many years to come, Austrian cultural life was characterised by a tendency towards conservatism, a broadly applied law against “filth and trash”, and a great loss of diversity, much of which had been “imported” by the occupying powers after the end of the war. Thanks to the IGNM’s international network, its events nonetheless developed into a platform for many international personalities. This infrastructure also made it possible for Cerha to meet people with greatly varied backgrounds:

The acknowledgment of the IGNM was not limited to the regional scene, but was instead international. As a result, many representatives of Neue Musik found their way to Waaggasse when they came to concerts in Vienna. I am grateful to the IGNM for the countless meetings, some of which were very important to me, and include names still known today, for example Milhaud, Honegger, Dallapiccola, Peragallo, Messiaen, Rosbaud, Maderna, Adorno, Stuckenschmidt, even Stockhausen, Berio, and Boulez. It was often impossible to discern whether an event was part of the IGNM or purely private—and it made no difference to anyone anyway.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 44 f.

Networking Underground

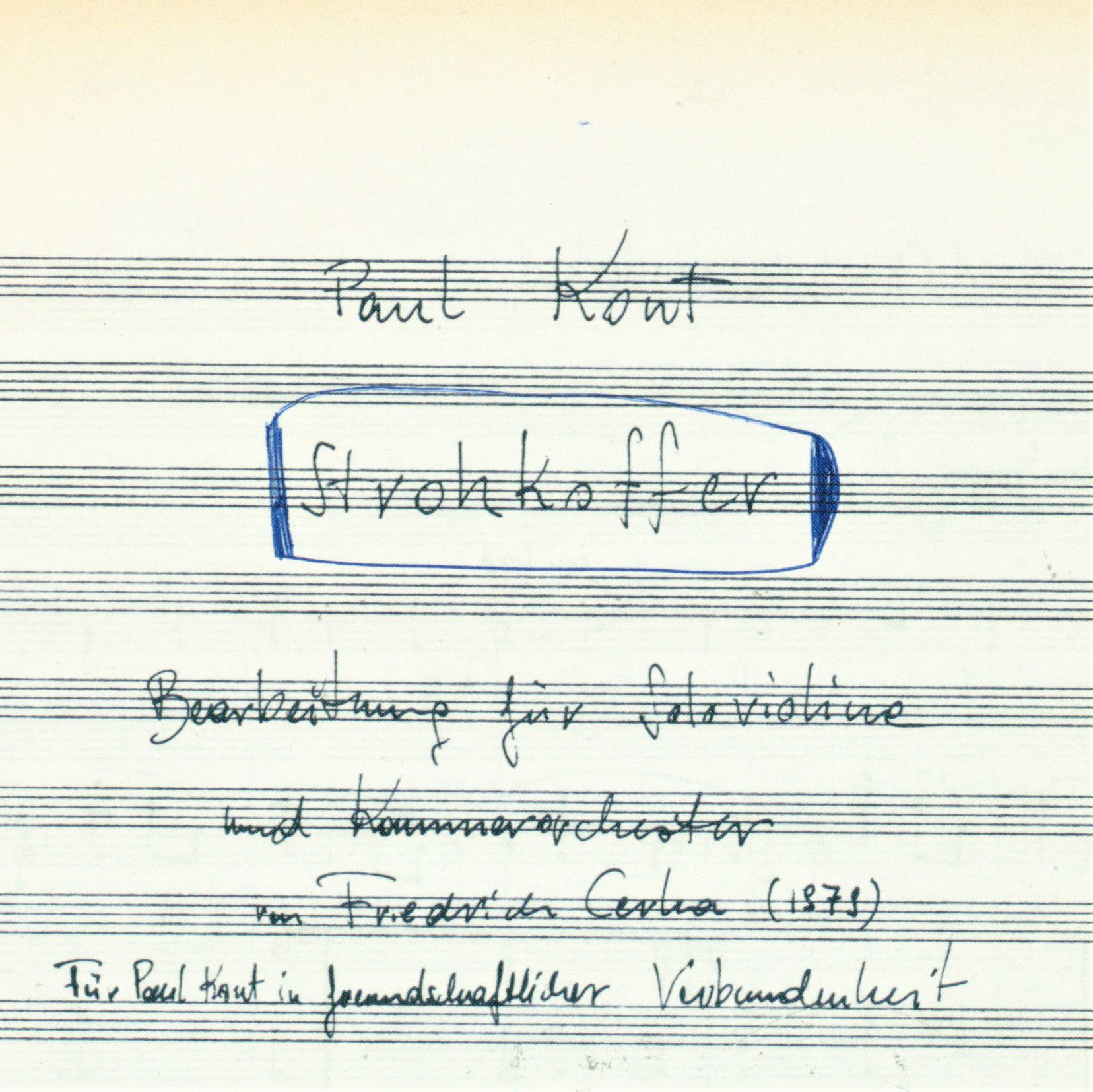

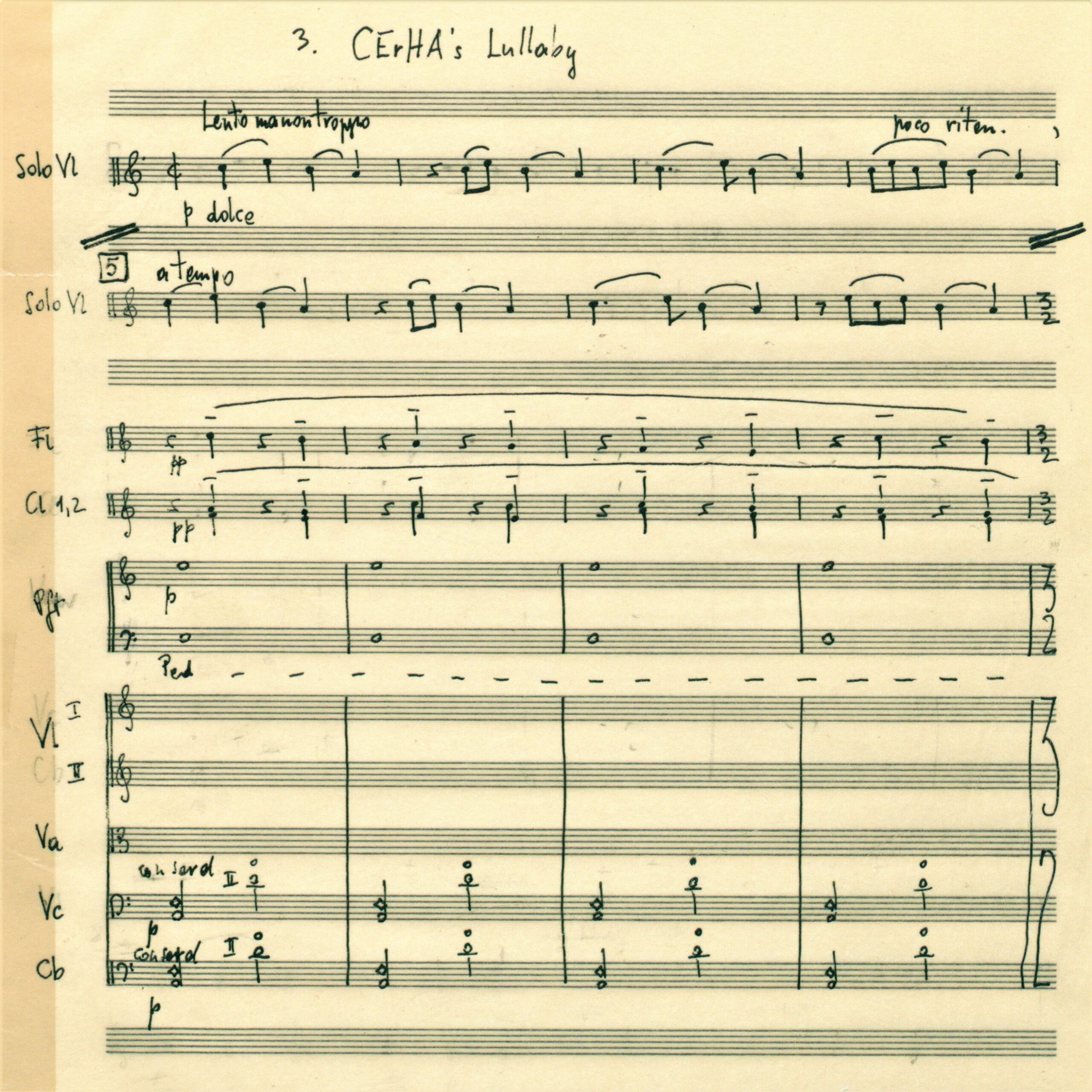

Cerha, Strohkoffer, instrumentation and arrangement of a piece for violin and piano by Paul Kont, “Cerha’s Lullaby”, AdZ, 00000082/16

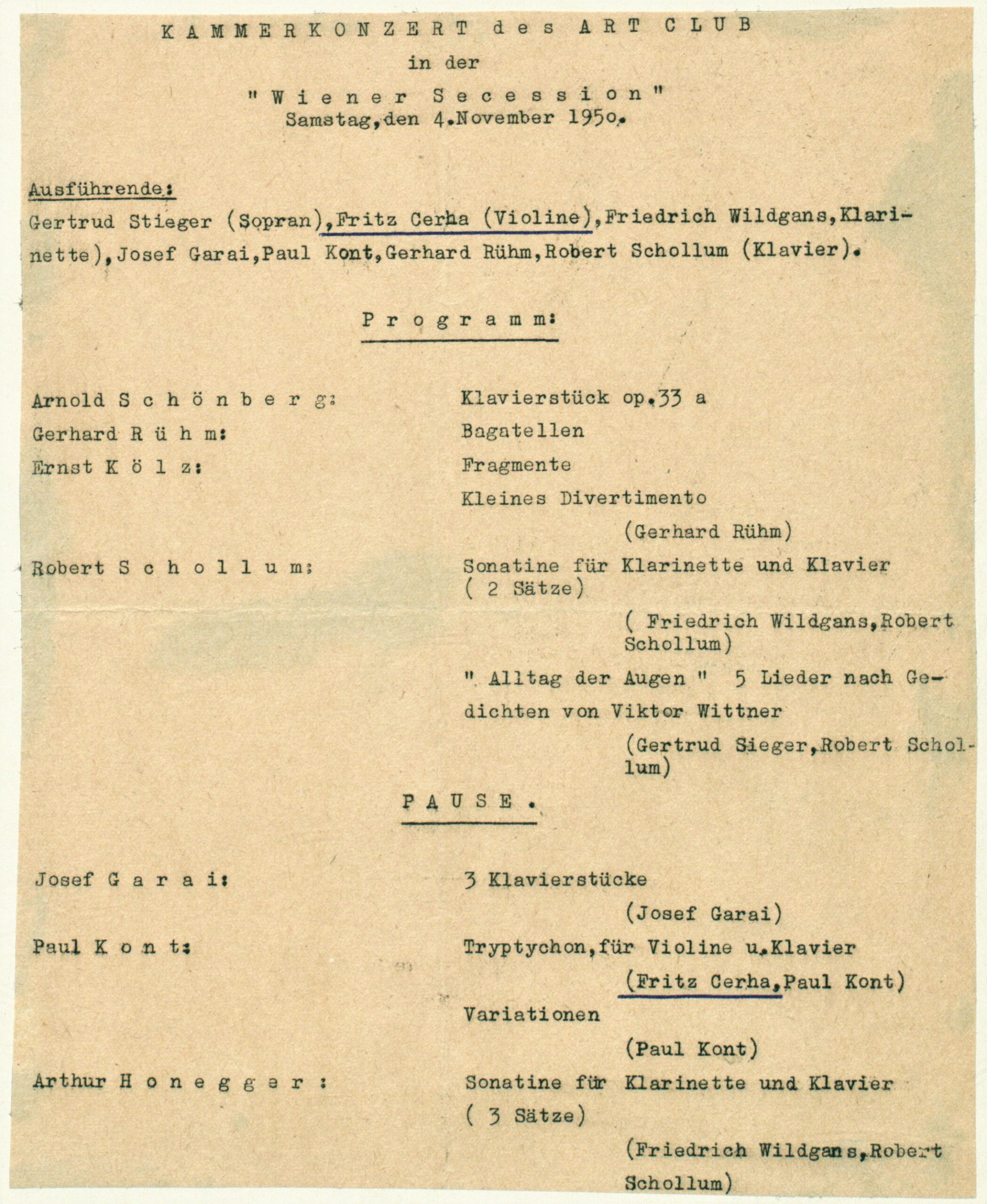

“Art Club chamber concert”, programme page, 4 November 1950, AdZ, KRIT0007/9

International Meetings

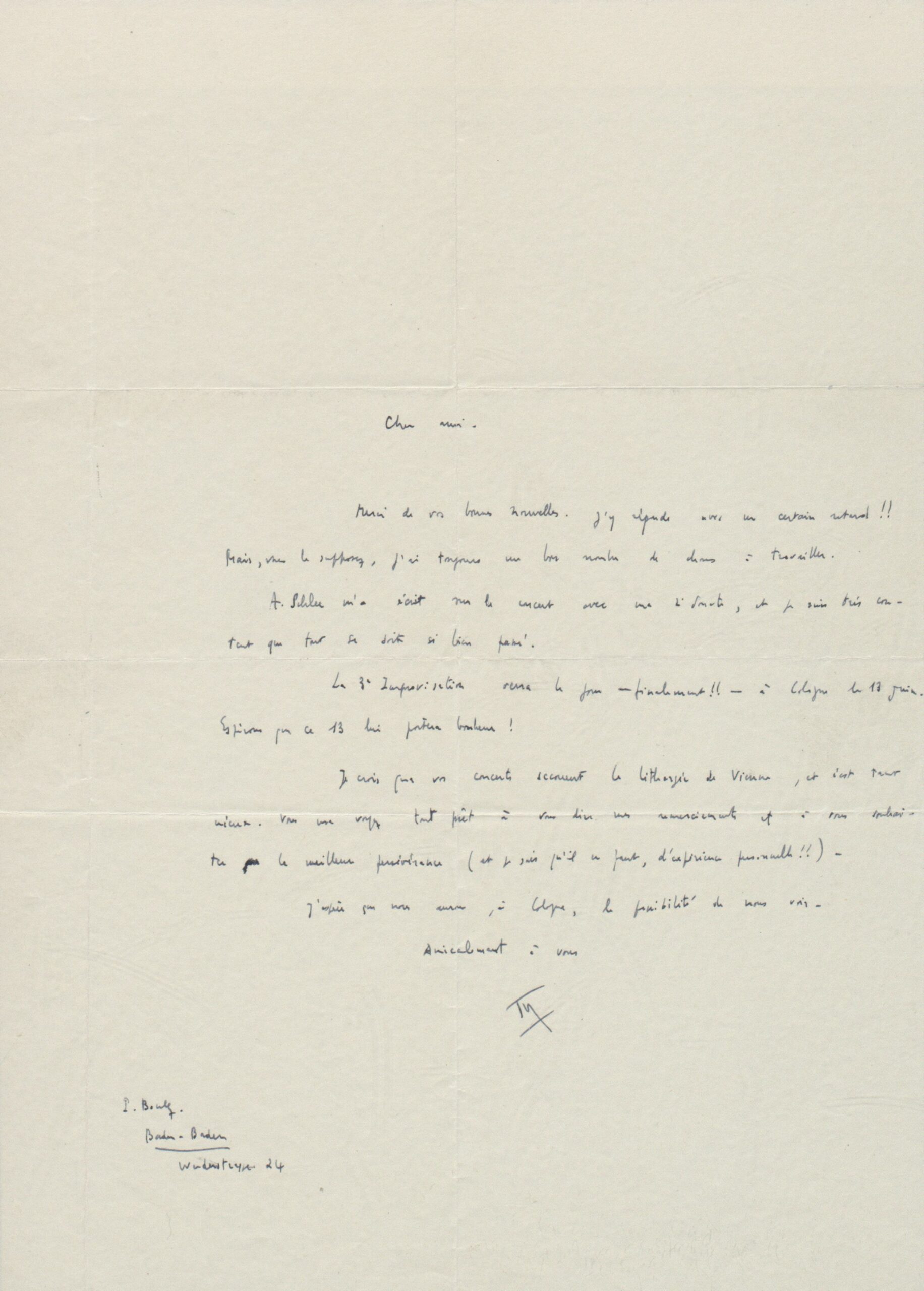

Now liberated from Austria’s deep-seated isolation, in Darmstadt Cerha was able to enrich his personal network with a great many international acquaintances. In addition to Karlheinz Stockhausen from Germany and Pierre Boulez from France, Cerha also met Luigi Nono, Sylvano Bussotti, and Franco Donatoni from Italy, Krzysztof Penderecki and Tadeusz Baird from Poland,See Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 33 John Cage and Stefan Wolpe from the US, Alois Hába from the Czech Republic, and Mátyás Seiber from Hungary. Cerha kept in close contact with several of them, including Cage and Boulez, after the summer courses, thanks in part to his work with the “die reihe” ensemble.

America, France, Italy: Three letters to Cerha from Boulez, Cage, and Nono, AdZ, BRIEF004

I met him in 1954 and continued to meet in various places throughout Europe until his death, most often in Vienna, of course. Our times together were always very enlightening, and he had a sense of humour that made things quite amusing. We told each other about remarkable young composers and interesting pieces, exchanged our experiences with percussive techniques, critiqued organisational methods and notational madness, discussed archaeological issues (a topic we were both very interested in and which he had extensive knowledge of), or simply indulged in malicious gossip accompanied by copious amounts of wine.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 33 f.

We sat for ages over the scores for his works Kette, Kreis und Spiegel, Sestina, and Hexaeder, with him trying to convince me of the logic of his approach, which he really wanted to stick with. Of course, he was fundamentally aware that history doesn’t stand still, and he began to suspect that general developments would at some point also move away from serialism.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Wien 2001, S. 35

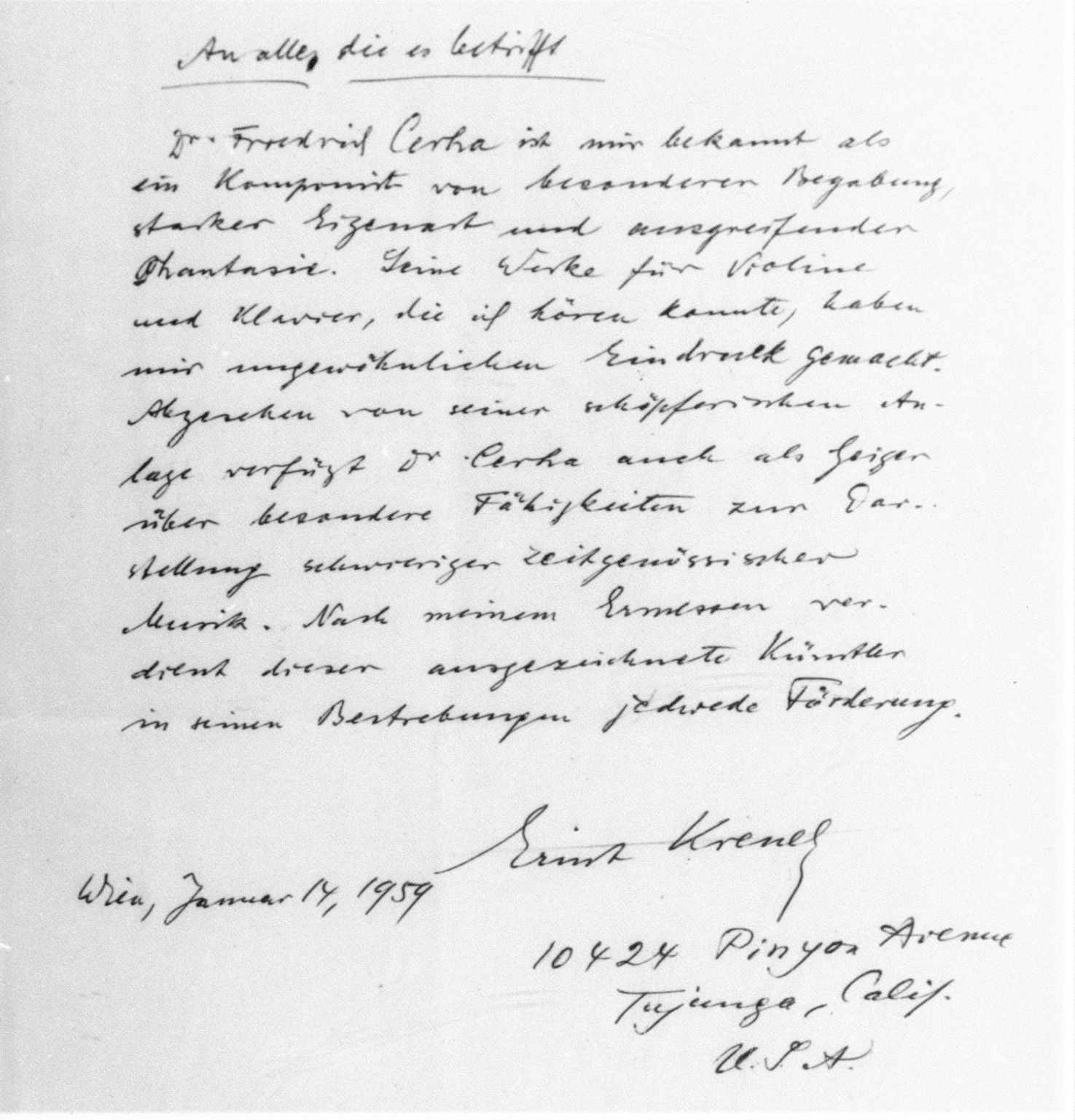

Beyond the summer courses, Cerha stayed in contact with Krenek until his death in 1991. Both strove to create opportunities for their works to be performed: As early as 1960, Krenek conducted the world premiere of Cerha’s Espressioni fondamentali, a central piece from his serial phase. And he supported his young colleague in other ways, evidenced, for example, by a general letter of recommendation dated January 1959.

Ernst Krenek, letter of recommendation for Friedrich Cerha, 14 January 1959, AdZ, BRIEF004/84

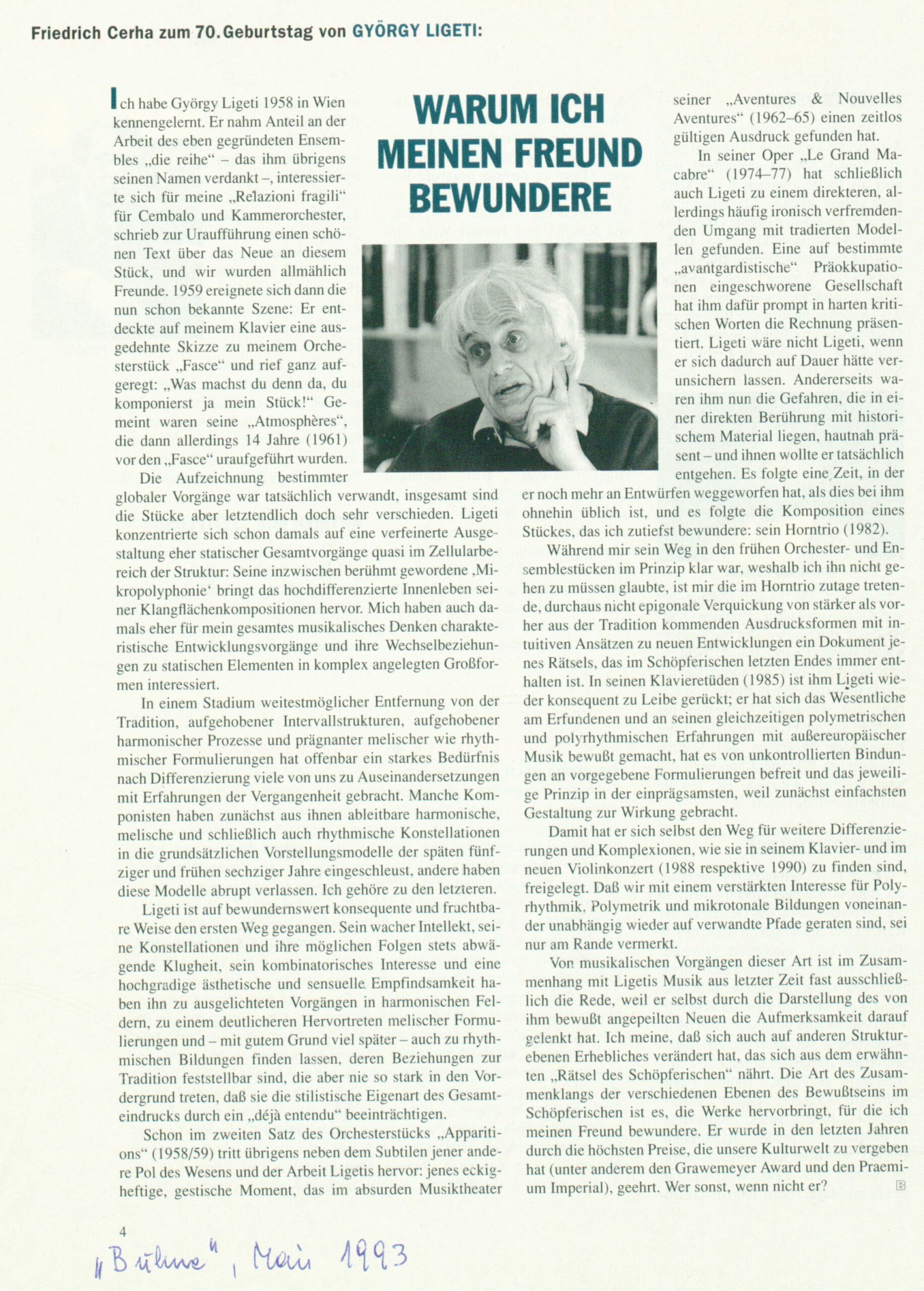

Cerha and Ligeti: Writings, each for the 70th birthday of the other