The Stone Sculptor

Cerha in front of a stone sculpture by Karl Prantl.

Cerha’s friendship with sculptor Karl Prantl provided the basis for Cerha’s artistic work with stones. One of Prantl’s large rocks is set in the garden at Maria Langegg—in the ideal setting, surrounded by largely untouched nature.

Photo: Hertha Hurnaus

As with almost every raw material he collects, Cerha also uses “his” stones as a creative element, though he did not begin to work them using tools until he was middle-aged. This crafting led to sculptures which did not take on “very human”See Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human forms and are neither representational nor artificially geometrical. Some of the stones hewn in this way remained autonomous sculptures, while others were given a purpose within a larger context—in Cerha’s self-built chapel in Maria Langegg, for example—a testimony to his irrepressible creativity, set in stone.

A Cornerstone Friendship

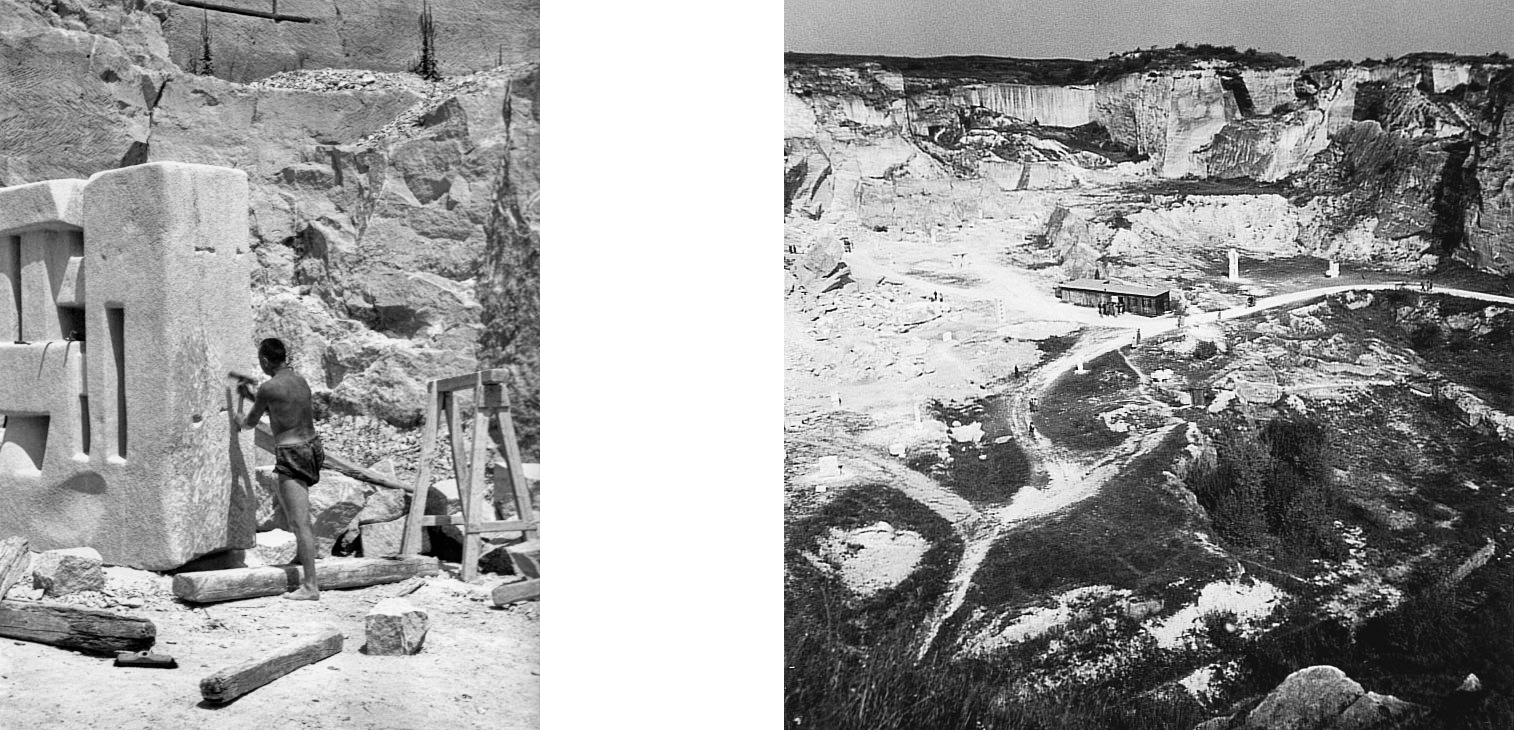

Karl Prantl working on Grenzstein (1958)

The Roman stone quarry in St. Margarethen during the Symposium of Young Sculptors

Photos:

Left: Wikimedia

Right: Karlprantl.at

Robert Neumüller, Die Steinspur. Der Bildhauer Karl Prantl, ORF production, 2002

After the first full performance of the Spiegel in June 1977 in Vienna, a celebration was held in Prantl’s studio in one of the large pavilions of the 1873 World’s Fair in the Prater park. Prantl approached Cerha, who was the last one to arrive, and said: “That was wonderful, Fritz—pick out a stone for yourself.” Cerha pointed to one of the largest, clearly the most beautiful one in his eyes, and said: “That one!” We didn’t hear anything for a while, but the following spring a call came from the Kunsttrans transportation company, informing us that they had a stone sculpture from Prantl to deliver. It now stands near the chapel in Maria Langegg, testimony to a friendship in more than one way.

Gertraud Cerha

Gertraud Cerha, correspondence for Cerha Online

In the decades to follow, the two filled the gap between stone sculpture and music with further tokens of their mutual admiration. In the mid-1980s, Prantl sculpted the Stein für Friedrich Cerha on Pöttschinger Feld; Cerha soon went on to compose an orchestral work titled Monumentum, a tribute to his friend, and wrote the ensemble piece Für K in 1993, its title indicating its dedicatee. Here, the sounds of a hammer and chisel can be heard in sections; like a sculptor, Cerha chips away at the rugged musical material with resounding blows on the anvil and flywheel.

Karl Prantl, Stein für Friedrich Cerha, Pöttschinger Feld, 1984–1987

Photo: Lukas Dostal, www.lukasdostal.at

Cerha, Für K (Ausschnitt)

Klangforum Wien, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha, Produktion col legno 2012

The suggestive sounds raise questions about the relationship between music and sculpture. Cerha searched for the answers by working and sculpting stones himself—supported by Prantl as a mentor and companion of ideals.

Hammer, Chisel, Grindstone

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

Like Prantl, Cerha’s stone sculptures are arranged in contexts with complexity. His property in Maria Langegg features large, covered slabs (see above) bearing numerous found objects. The stones create an “omnium-gatherum”, with differing sizes, shapes, patterns, colours, and potential for association. This reveals something that is typical of Cerha in both his painted as well as his musical works, a recognizable design feature that surfaces again and again: the unity of what is different.

Cerha’s collage of stones reveals his desire to assemble and contrast, while other pieces show an inclination to detail. This design principle, dedicated to timely precision, forms another arm of his branched oeuvre (one reflected especially clearly in his sound compositions). Many of his early sculptures in particular owe their existence to his fondness for collecting. Cerha began working on stones found in nature, polishing them, in the 1960s.

Two sculptures finished in 1967 are good examples of his way of adapting found objects. He discovered the fascinating stones “during a family stay in Istria”, a peninsula situated between Croatia and Slovenia.Gertraud Cerha, correspondence for Cerha Online “The fundamental shapes of the stones” prompted him “to take them with him and later grind them into their final shape.” The finished sculptures have a visibly succinct originality. One sculpture tapers into points on the sides. A hole in the middle is reminiscent of Prantl’s stones, but is less symmetrical and coarser in comparison. The other sculpture is suggestive of a torso. Cerha mounted the stone on a pedestal, increasing this impression. The allusion is vague, however, arrested in the grey area between concrete and abstract. The two stones are both objets trouvés and consciously shaped sculptures.

Cerha, stone sculptures, both 1967

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

Cerha, Mühldorf granite stone, late 1960s

Left: Joachim Diederichs: Friedrich Cerha. Werkeinführungen, Quellen, Dokumente, Vienna 2018.

Right: Christoph Fuchs.

Cerha, Urstromtal, marble, ca. 1980

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

Stone on Stone: “Projekt K”

Cerha in front of his chapel in Maria Langegg

Photo: Hertha Hurnaus

Side and front of the chapel

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

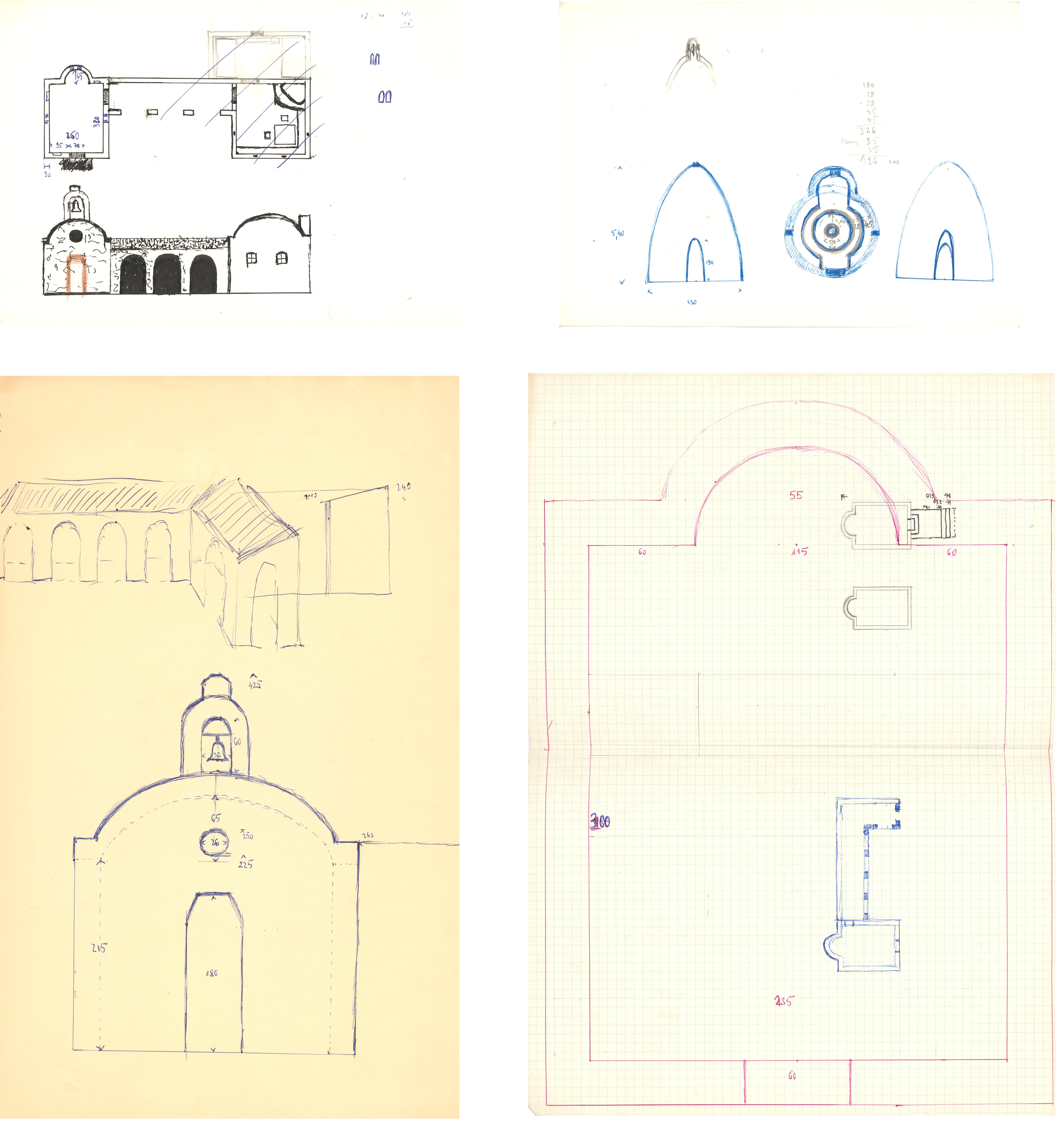

The construction of the chapel may be comparable to the Sisyphean efforts that go into the composition of an opera: They both share the need for careful planning and staying power. It took Cerha about 20 years to complete the chapel; as a busy composer and conductor, he was only able to devote himself to working on it for limited periods of time. He made the first sketches in the 1960s. They are titled “Projekt K” on one sheet—a reference to the German word for chapel, Kapelle—as well as an initial nod to Karl Prantl and the ensemble composition later dedicated to him titled Für K. In themselves, the drafts for the chapel are an artistic achievement, drawings filled with architectural vision and pictorial power. The extent to which Cerha was preoccupied by the project is shown by his sketched sheets for musical works, sprinkled here and there with images of the chapel façade and floor plan—for example, on sketches for Intersecazioni and Fasce, two orchestral works composed in 1959 that Cerha revised around 1973, at a time when he was feverishly working away at the chapel.

Cerha, plan drawings for the Maria Langegg chapel, undated, AdZ

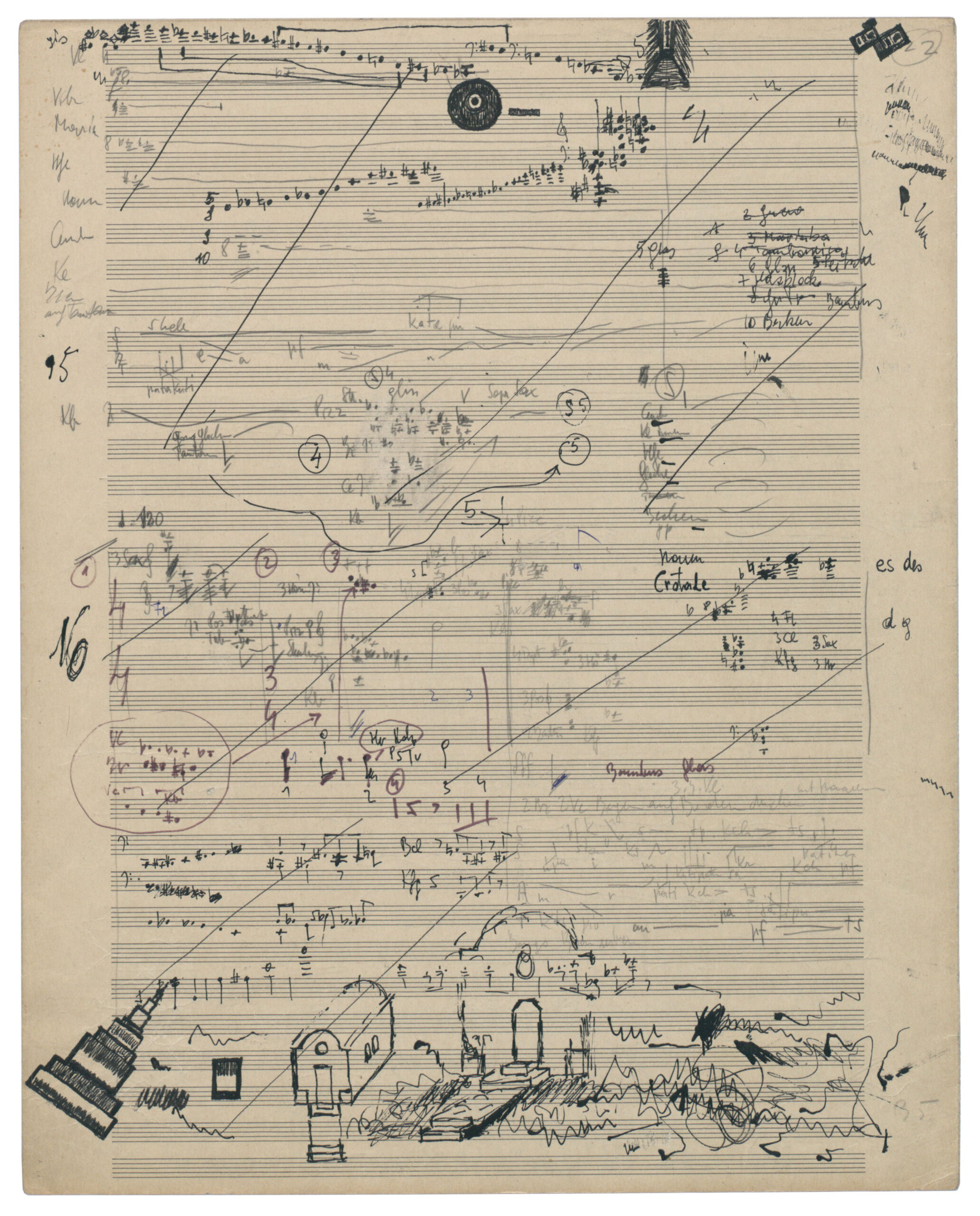

Cerha, sketch for Intersecazioni, 1959–1973, AdZ, 000S0054/36

Cerha, chapel in Maria Langegg, interior

Photo: Christoph Fuchs