The Global Citizen

Cerha at Lamsenjoch, Tyrol.

During and shortly after the war, Friedrich Cerha worked as a hutkeeper in the Tyrolean Alps. In 2005, at the age of 79, he returned to that place of freedom. Director Robert Neumüller shot scenes for a film portrait of Cerha, titled So möchte ich auch fliegen können, or “I too would like to fly like this”.

Photo: Robert Neumüller

Cerha’s passport, pages 2–3 with personal data

In the early stages of our modern times, humanity’s relationship to the world began to change significantly. Sea voyages and research expeditions opened up new regions, even continents, previously unknown to Europeans. This “Age of Discovery” did not leave the field of Western art untouched. Artists ranging from Albrecht Dürer to Paul Klee began to travel, gaining stimulating, lasting impressions on their journeys. “Grand tours” took writers such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Hans Christian Andersen to the Mediterranean, for example. Italy became a particularly desirable destination, increasingly sought out by musicians, whether Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, or Hector Berlioz. The inspiration of the distant, of distance itself, stimulated cultural exchange—and with the advent of technology, distances between different cultures have been decreasing (more than just geographically) ever since. Intercultural exchange continues to shape the present day, condensing the “world into a networked system”, something Cerha had already anticipated as early as the 1980s.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 84 And in this networked and interconnected world, he remains a free citizen.

Eastern Roots

Cerha, Sieben Stücke für Mandoline und Gitarre, “I. Fernöstlich”, 2014, AdZ, 00000198/2

Cerha, notes on a possible ancestor, undated, AdZ, SCHR0027/2

Cerha, Slowakische Erinnerungen aus der Kindheit, sketch for “Eine Gänseprozession versperrt den Weg”, AdZ, 000S009/51

Two photos from Cerha’s childhood, ca. 1940

Blossoming Worldliness

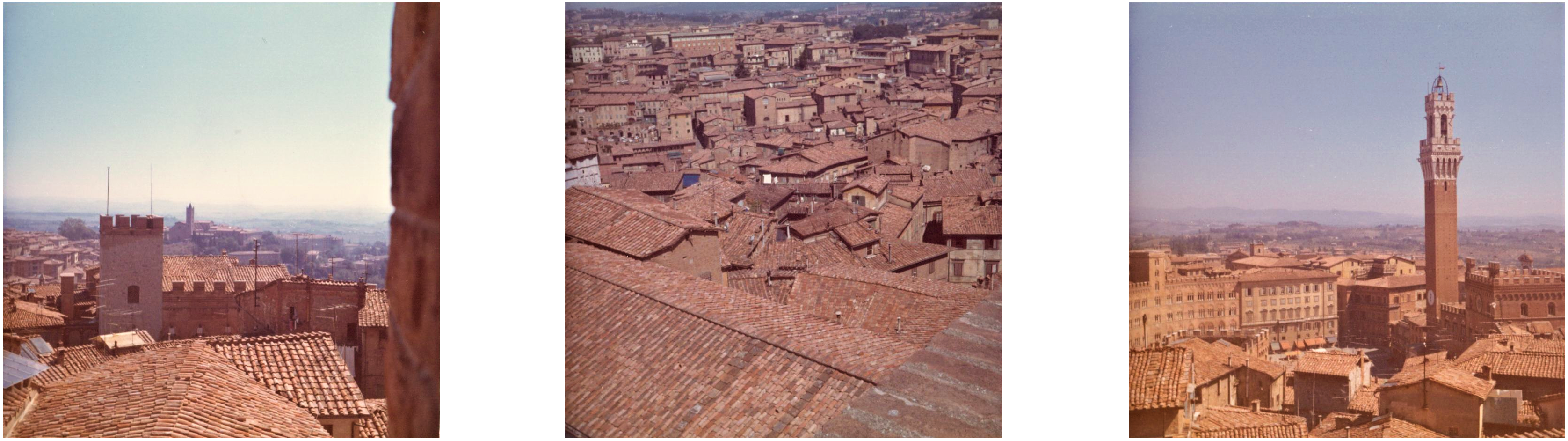

Cerha’s carefree, culturally colourful childhood ended with the war. After this abrupt end, he needed to regain his independence—and the experience of freedom he had gained in 1945 as a mountain guide in the Tyrolean Alps was useful in this regard. His bond with nature, strengthened during this time, made it more difficult for him to re-integrate into society. On the other hand, rediscovering urbanity also opened up countless opportunities for him to explore the “whole wide world”. Cerha soon began travelling to other countries, broadening his horizons. One of his favourite destinations was Italy. In the early 1950s, he travelled to Bologna for the first time. Wanting to shine a light on baroque music, which had been largely forgotten, he visited the Biblioteca del Conservatorio and the Accademia Filarmonica. He copied the scores he found there by hand—with the goal of performing them in Vienna. Further trips to Italy followed: to Florence, Naples, and Rome. Cerha spent the most time in Italy’s capital. He lived there from the beginning of February to the end of June 1957—a sojourn made possible by a grant from the Austrian Federal Ministry for Education. The composer was inspired by the Mediterranean way of life, its culture, and the music of the nation. Relazioni fragili and Espressioni fondamentali, two important works written in Rome, exude an international esprit—and not just due to their Italian titles. Inspired by the debates of the Darmstadt avant-garde, Cerha worked on these critical Austrian contributions to the current compositional style, serialism, while living in the Italian metropolis. Looking back, he says: “For a long time, it was important for me to see myself as a citizen of the world, and I also saw myself as making music that fit this view.”Thomas Meyer, interview with Friedrich Cerha, https://www.evs-musikstiftung.ch/de/preise/preise/archiv/hauptpreistraeger/friedrich-cerha/interview.html

Photos from a trip to Italy, from Cerha’s private collection

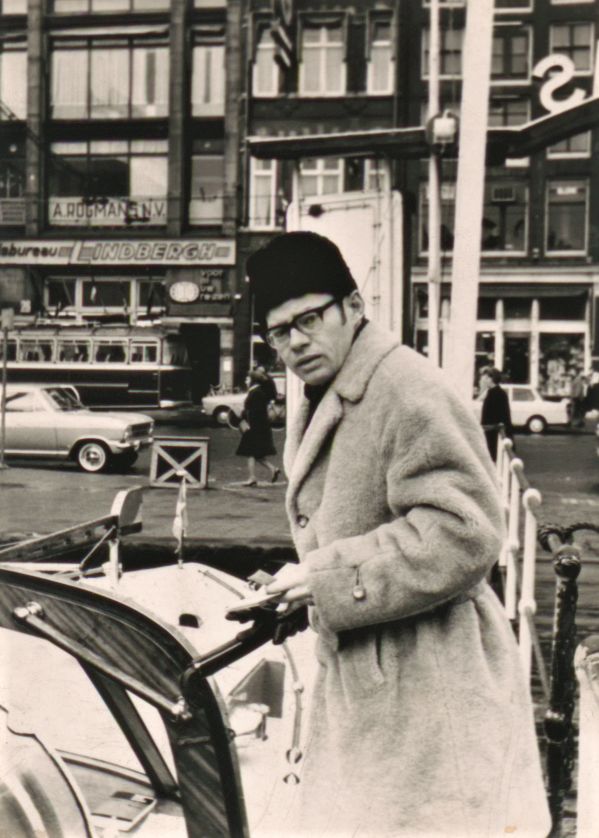

It was not only as a composer that Cerha felt open to the world. The activity that most ushered him into the international arena was conducting, above all as the leader of the “die reihe” ensemble, which he co-founded in 1959 in order to bring new international music to Vienna. His achievements as head of “die reihe” soon resulted in numerous guest performances: in Paris, Warsaw, Hamburg, Stockholm, Brussels, Prague, Zagreb, Rome, Berlin, Budapest, Amsterdam, and Venice (to name just a few). As a result, Cerha began receiving increased attention beyond the ensemble, as a conductor and specialist in contemporary music, and as such received invitations both at home and abroad.

Cerha in Amsterdam, 1962.

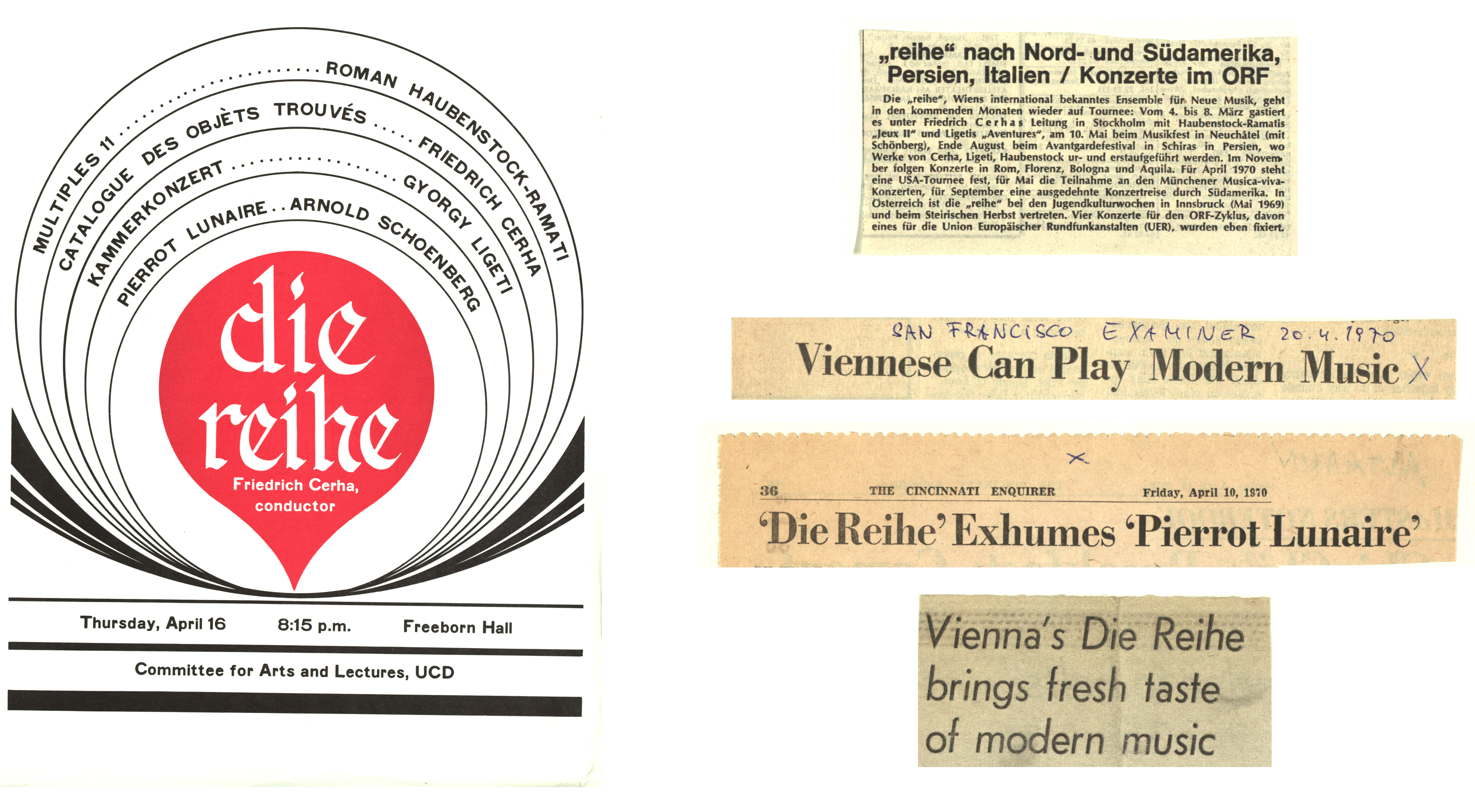

One concert tour of “die reihe” stands out. In April 1970, after many successful European performances, the group made the great leap across “the pond”. For a month, Cerha travelled with his musicians through North America, from the Canadian capital of Ottawa and on to the USA: Maryland, Massachusetts, Cincinnati, Ohio, Wisconsin, Illinois, and finally California. The musicians mainly performed in university auditoriums. The programme: pure Austria, an “exported hit”. The core repertoire included Arnold Schönberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, Cerha’s own Catalogue des objets trouvés, Roman Haubenstock-Ramati’s Multiple II, and György Ligeti’s Kammerkonzert, which was written for “die reihe” and premiered in Ottawa. With the exception of Schönberg’s 1912 melodrama, none of the key pieces were composed before 1969. Cerha was steadfast in his aim of presenting a refreshing, up-to-date programme, thus giving Viennese music a place on the world stage.

Documents on the American “die reihe” tour, all from 1970

University of California concert poster, Davis (left), Vienna newspaper article (top right), headlines from the San Francisco Examiner, the Cincinnati Enquirer, and the Chicago Sun-Times

In America, Cerha was met by audiences that were as knowledgeable as they were enthusiastic. The media also celebrated the ensemble. It almost seemed as if “die reihe” was more welcome here than in Vienna. Slowly but surely, however, the tide began turning in Austria as well—thanks to Cerha, who had been bringing international Modernism into the capital for years.

The era of such grand tours came to an end over the course of the 1970s, although “die reihe” continued to make guest appearances abroad—in London, Madrid, and Barcelona, for example. Travelling remained important to Cerha not only in his role as a conductor; increasingly, his artistic work was deeply influenced by inspiration from around the world.

“die reihe”, returning from their American tour, 1970

Traces of the World

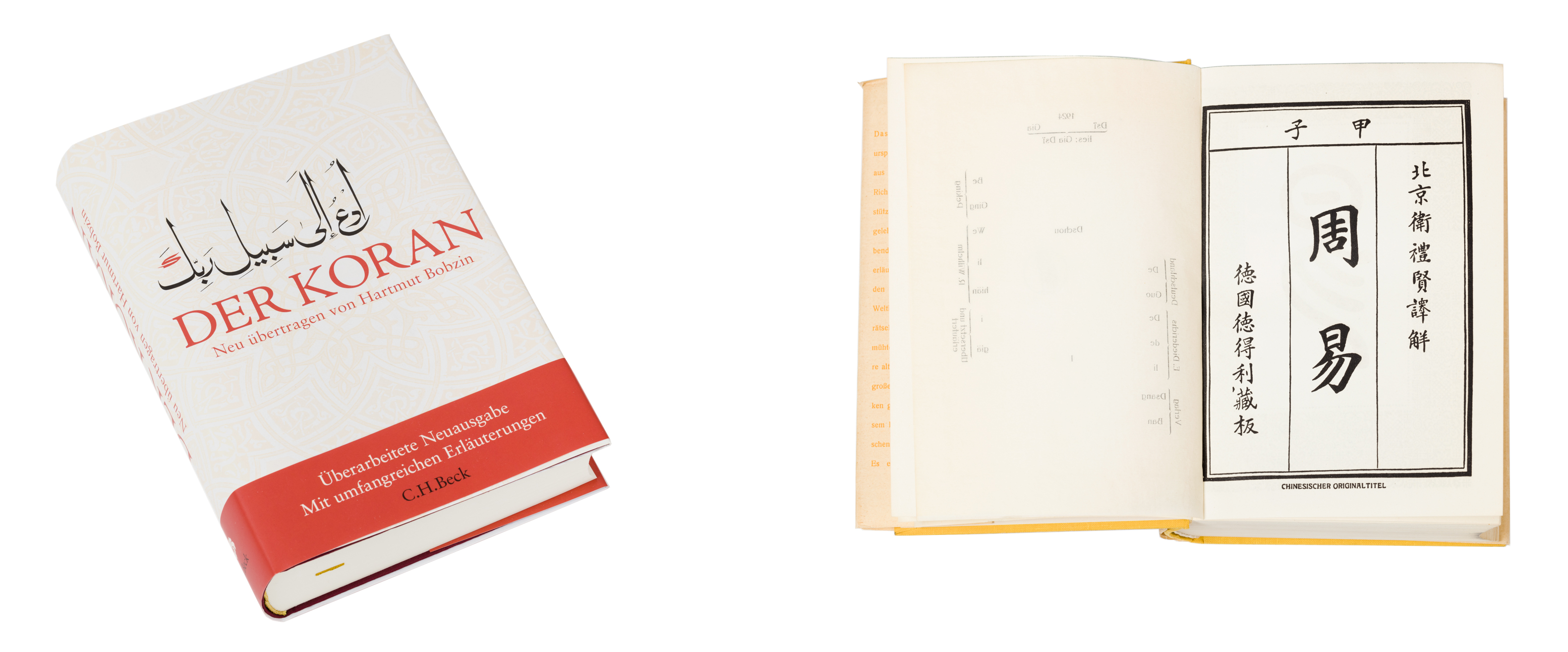

He was also influenced by Asian spirituality, inspired by the “Far Eastern worldview”Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 32 of Josef Matthias Hauer, and Zen Buddhism à la John Cage, colleagues with whom Cerha also formed personal friendships. In 1952, fascinated by “thinking in changes” and “developmentlessness”,Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 219 he set to music a section of the Chinese I-Ching, an ancient collection of calligraphy and sayings from the third millennium BC. Unfortunately, the manuscript of this fragment has been lost.

Koran and I-Ching, Cerha’s private copies

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

Cerha’s visual works also reveal a kind of universal spirituality. Private photographs of his travels tell of his love for architecture, sculpture, and nature. The family travelled to Crete in 1969, visiting ancient archaeological sites such as the Minoan palace of Knossos—sunken worlds that never lost their aura. The sight of these magnificent columns and ruins, thousands of years old, turned Cerha into a builder: His Mediterranean-esque chapel in Maria Langegg is his only architectural creation, but it is an eloquent example of how his impressions of the world interacted with his (literally) hand-made design.

Impressions from Crete, Cerha’s private photos

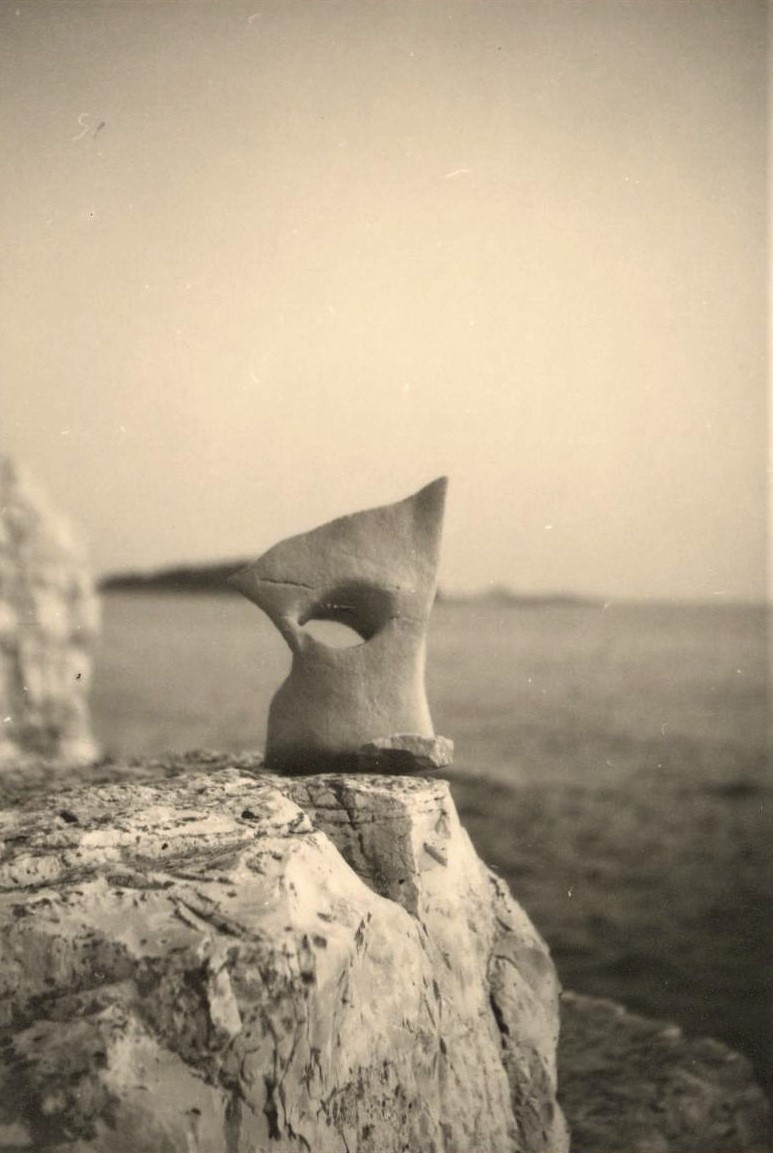

A sculptor and collector, Cerha tracked down raw materials for sculptures and assemblages during his travels. How much of his travels he integrated into his creations is difficult to say—after all, it is impossible to guess the origin of many of the found objects he used. Other artworks, in turn, boldly announce their inspiration: In the northeast Italian port city of Trieste, he found unusually shaped rocks in the 1960s—natural materials in the best sense of the term. He transformed them into art, sanding them down and placing them on a base. The resulting objets trouvés are a combination of the dual joys of creation and discovery.

Rock from Trieste, presumedly at the location where it was found, Cerha’s private photo, 1960s

Elsewhere, it was sounds that sparked Cerha’s imagination. In 1989, at the same time he was rediscovering and processing the Slovak melodies of his childhood, several non-European cultures entered his field of vision. He was strongly influenced by a spring trip to Morocco. He stayed in the south of the country for a long time, and was thus able to research the musical culture and history of the region. “Experiencing live Arabic music” was ultimately the “direct triggering moment” for his first string quartet, which he composed largely on site.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 259 Cerha had not been entirely oblivious to Moroccan culture before this. At university he had studied Islamic culture, as attested to by his compositions from the time, Zehn Rubaijat, which are set to ancient Persian poetry. But in the late 1980s, for the first time, the sounds of far-away truly began to settle into his music. The way he processed them is revealing: Cerha incorporated quarter tones in the quartet for the first time (something not found in Western music) and used the old Arabic “maqam” technique alluded to in the subtitle. However, the piece does not sound particularly oriental. Rather, it shows “how the creative imagination was inspired by musical conditions and constellations that do not exist in our part of the world,” says the composer.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 259 Other pieces can be interpreted the same way—for example, a work with its “ear” tuned towards Oceania, Zweite Streichquartettor the multicultural Phantasiestück in C.’s Manier. Cerha did not visit all the places that can be heard in his music. He didn’t need to travel to Papua New Guinea, for example, to become fascinated by the ancient indigenous culture situated around the tropical Sepik River, a culture that survives to this day. Curiosity was enough to inspire him to strike out from his own familiar world into unexplored horizons.

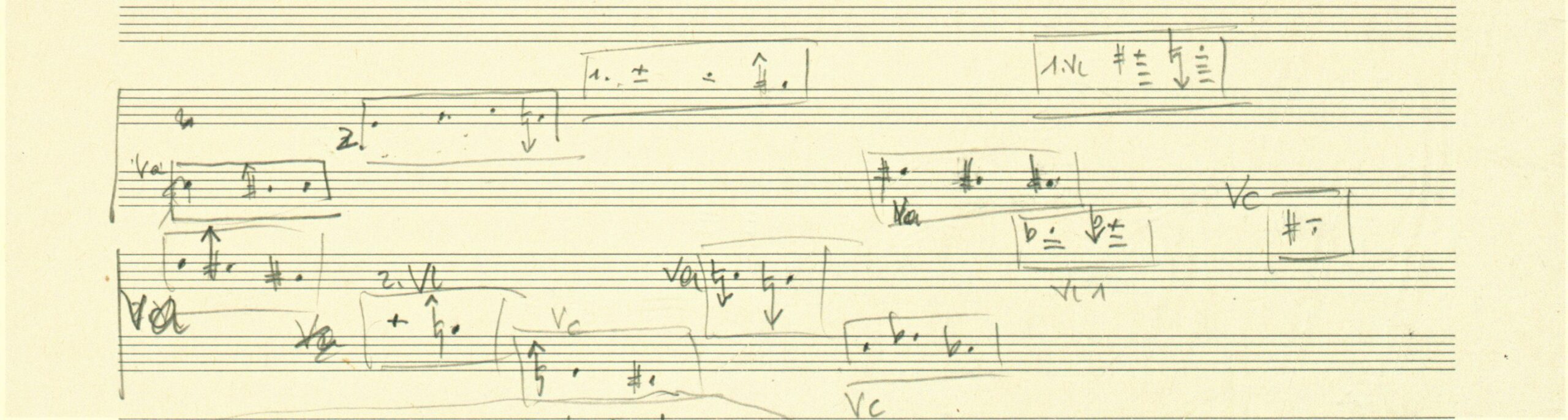

Cerha, 1. Streichquartett “Maqam”, sketch with quarter tones, 1989, AdZ, 000S0104/14