The Painter

Cerha in his art studio

The studio in Maria Langegg helped shape the painter: This is where Cerha created almost all his paintings over the course of his life. A small barn in the midst of nature, the studio is a site of artistic contemplation, organic life, and natural experience.

Photo: Hertha Hurnaus

Paintings and sculptures; attic of the Cerha home; Maria Langegg

Foto: Christoph Fuchs

Painting as an Organic Expression of Life

Cerha’s studio in Maria Langegg

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

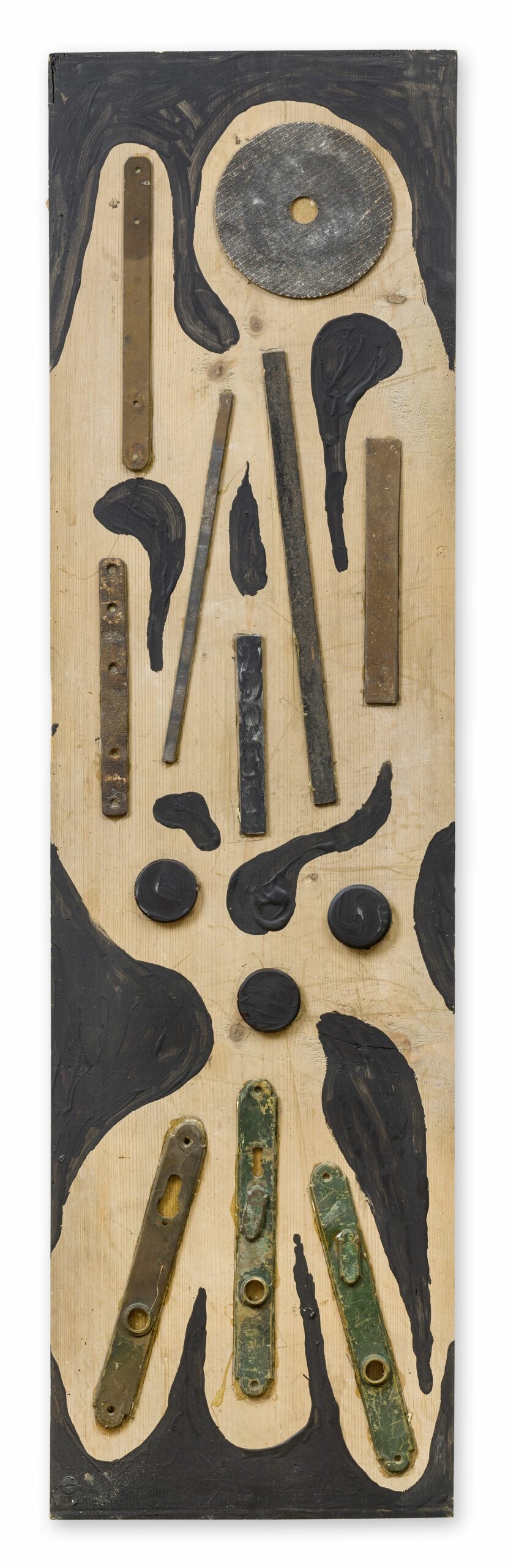

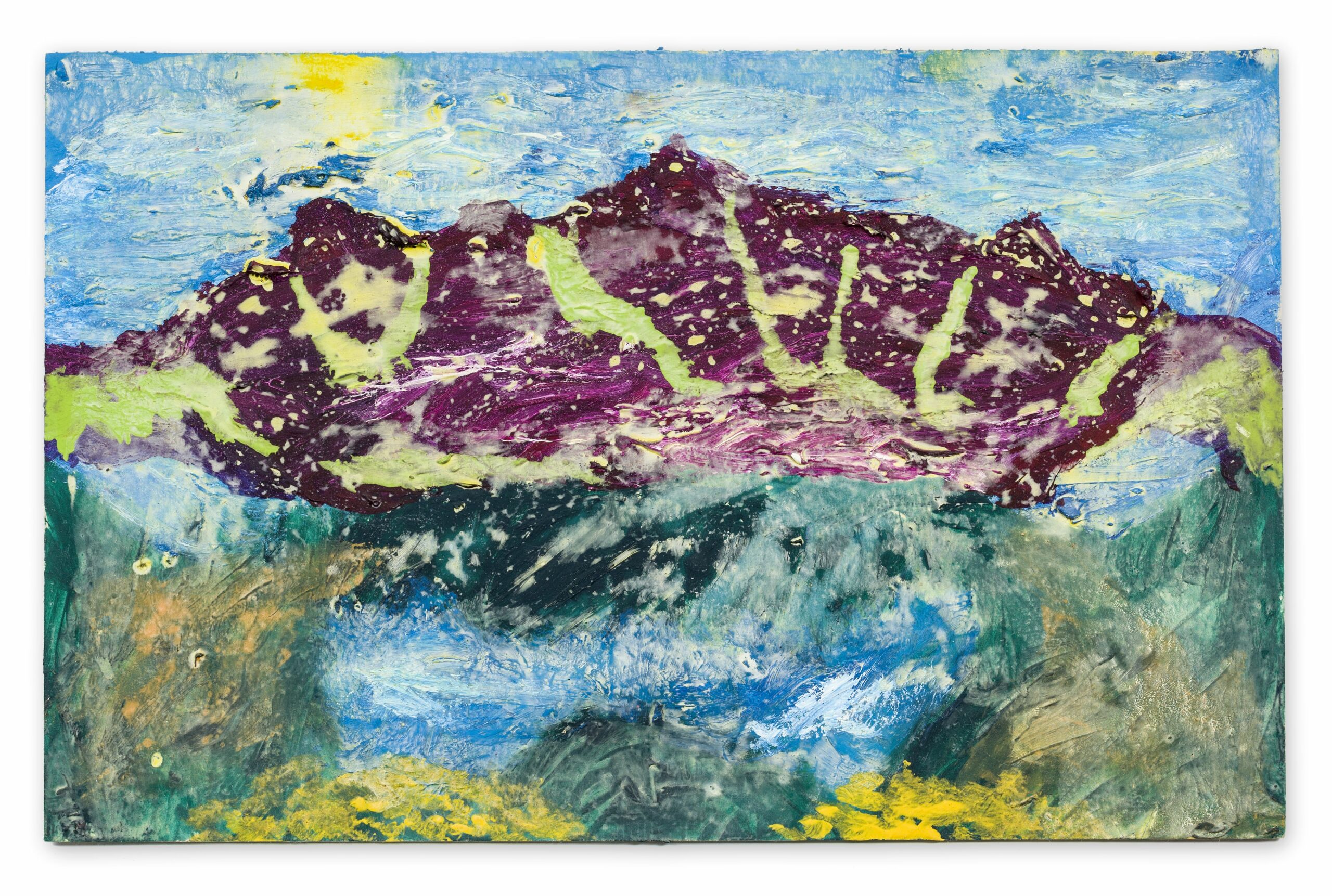

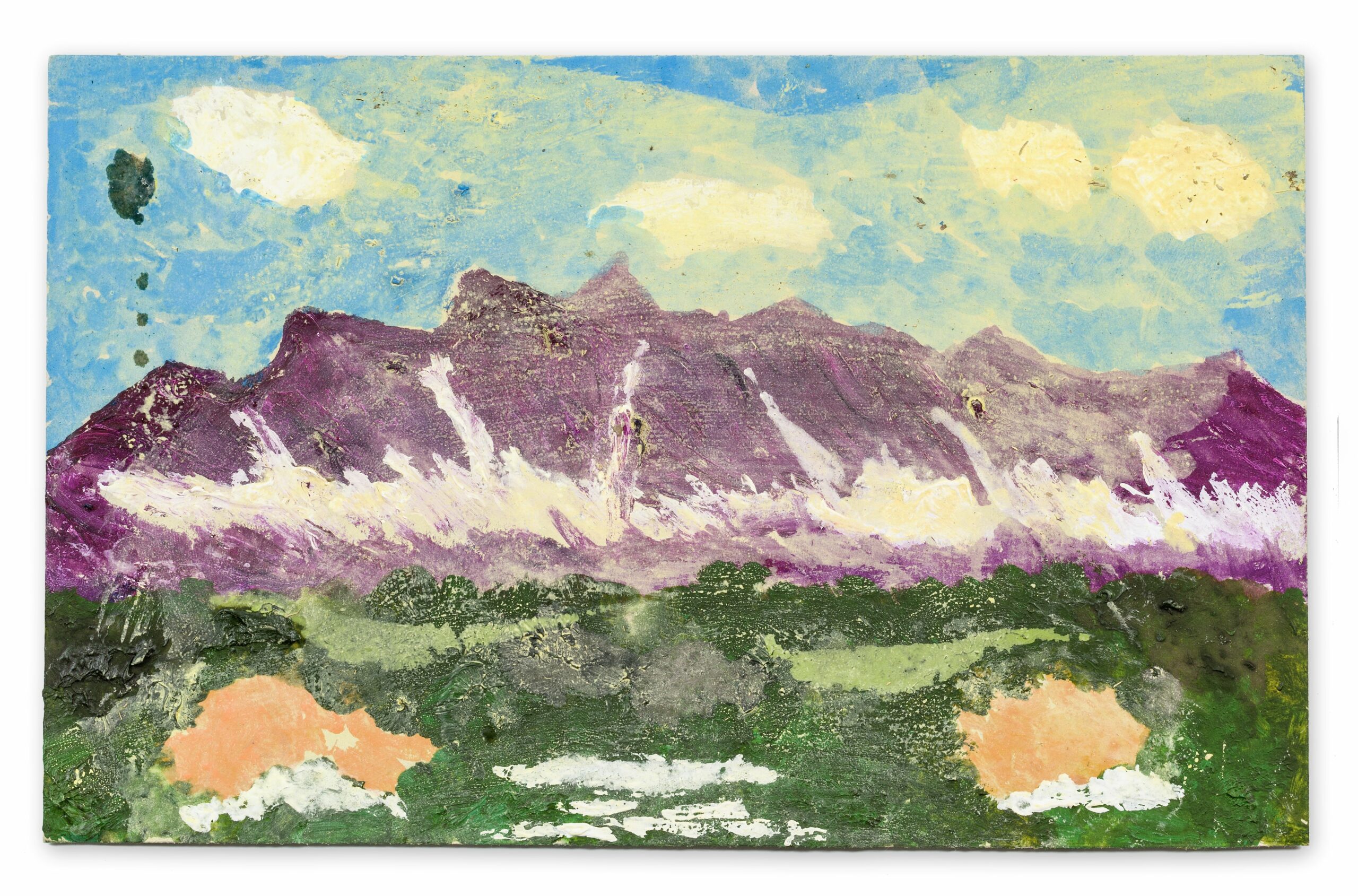

Within this analogy of writing and painting, Cerha’s descriptions of the physicality of shaping can be broadened quite easily: The application of paint puts the creator into direct contact with the material and can likewise be seen as an “organic expression of life”. With Cerha, the reference points of production can also be expanded: His paintings are not only influenced by the colours he uses, but also by the way he attaches objects to them. And even more: This gathering of objects can be understood as an elemental part of his creative work. Behind this productive painter lies a passionate collector. Regardless of whether these things are part of nature or the human world, Cerha has been appreciating and preserving them since childhood.

Over time, his studio—a small wooden hut in the forest, not far from his home in Maria Langegg—became a gathering point. An aura of seclusion envelops the workshop. Some may be reminded of Gustav Mahler’s little composing hut in the midst of a forest glade above Lake Wörthersee: a site of extreme concentration, of the (mental) compression of material. In Cerha’s hut, one finds the countless materials he uses in painting. Scattered objects of various origins (often natural materials), half-used buckets of paint, pots and vessels, spatulas, brushes, pens, fabrics, boxes, wood and paper used to paint on, and unfinished paintings. Here, there is no room for organisation in the traditional sense, yet all the better for creative communion with nature. This is where it becomes clear that Cerha sees painting and design as a means of absorbing the world: Things find ways to come together, always in new combinations. They are redesigned, brushed over (not only metaphorically), and enter into symbioses with other things, sometimes with things that are seemingly opposite. This vibrant interaction of objects is Cerha’s major artistic theme.

Cerha’s studio in Maria Langegg, details

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

A Small Retrospective: Objects of the World

Timewise, the increased focus on assemblage coincides with Cerha’s beginnings in the field of object art—an observation that is indicative of his progressive, yet independently developed, fundamental mind-set. Other influences from art history can also be found in Cerha’s work without being too overtly foregrounded. Theresia Hauenfels compared a 1964 painting with the Arte Povera (“poor art”) that emerged in Italy only a few years later. The artists of this movement, like Cerha, worked with everyday materials (such as stones, wood, earth, ropes, felt, dishes, and pieces of broken glass), emphasising their expressive value. During the same time period, everyday objects also played an important role in Fluxus: They were used to shatter the boundaries to life—in music and elsewhere (think of, for example, Water Walk by John Cages, made with the “instruments” of hand blender, bathtub, bottles, radios, and more).

Cerha’s assemblages are similarly interested in the reinterpretation of familiar objects: With great imagination, screws, nails, coins, fountain pens, and razor blades are reassembled to create a new whole. Sometimes the objects stand almost on their own, remaining clearly recognisable for what they are. Sometimes they are almost “melted down”, as in a 2013 painting with a pile of small keys pasted over with glue to form a fermenting, muddy mass (left).

On the other hand, entirely different paintings use the geometry of the objects to integrate them almost imperceptibly into a structured play of shapes. The basic elements can usually be reduced to only a few denominators. The dying of the wooden panels emphasises the artist’s interest in structure, dividing the image space, and creating a context with what is glued onto it. “For me,” says Cerha, “there is a dialectical relationship between the foundation and the objects. These are simply two levels that each stand for themselves, so to speak.”Theresia Hauenfels, “Sequenz & Polyvalenz. Überlegungen zum bildnerischen Werk von Friedrich Cerha”, in: Gundula Wilscher (ed.): Vernetztes Werk(en). Facetten des künstlerischen Schaffens von Friedrich Cerha, Innsbruck et. al. 2018, pp. 111–117, here p. 112

As in Cerha’s musical work, his visual work contains oppositional ideas. The strictly geometric compositions contrast with images that are characterised by having almost no sharp contours, instead left consciously shapeless. Here, the sculpturality fades into the background or even disappears entirely. Instead, an openly appealing, expressively powerful path based on organic imagery is realised. Colour becomes a dynamic element, as seen in a 1970 painting in which Cerha poured large areas of paint onto a wooden panel, letting it flow down, a technique reminiscent of the informal painting of the 1960s. In Vienna Actionism, it was the large flow painting of Hermann Nitsch that attracted particular attention. He, too, poured buckets of paint on canvasses, creating an almost orgiastic effect. Cerha was, of course, familiar with Nitsch and his fellow adversaries, although by no means can his poured paintings be categorised as Actionism. The colour-rich splash and flow effects dominate the image, but are again only one element in a heterogeneous composition. The ground has been worked with a brush, the area split in half by a long, blue line. The upper part of the paintings is filled with earth and small stones (in some pictures sand is used). Three layers are superimposed one atop the other, yet without diluting the sense of spontaneity.

In terms of my work, the stylistic diversity, the different materials, and the way they are handled are often mentioned. […] And it is indeed true that works with very different natures were created at neighbouring times. This is due to the fact that in several phases of my development, I started with one point and followed it along various evolutionary paths that diverged in different directions. This means that directly comparing things that were created at the same time can lead to a somewhat perplexing determination of “diversity”. If one wants to pursue the evolution of a specific development […], one must therefore relate each work to earlier works along its development path in order to gain insight into the logic of the development line.

Friedrich Cerha

Cerha, comments on Drei Sätze for an orchestra, https://www.universaledition.com/friedrich-cerha-130/werke/3-satze-14495

It is significant that this explanation (excerpted from Cerha’s commentary on Drei Sätze for an orchestra, 2012) is not about his visual, but his musical works. However, it also applies to Cerha’s paintings and assemblages. This ongoing parallel work on music and painting also raises the exciting question of how they are connected.

A Dialogue of Music and Art

To date, Cerha has created more than 1,000 paintings and 200 compositions. Yet hardly any of his paintings explicitly refer to his music, and vice versa. Strictly speaking, there is not a single example of a one-to-one transferral. Certainly, however, a few connections can be observed—ones that are always rooted in the spectrum of a specific topic, and can thus be assessed as a twofold expression of the same subject.

A first interrelationship of this nature centres around a drama with which Cerha occupied himself for almost three decades starting in around 1960: Bertolt Brecht’s play Baal. Cerha did not complete his opera of the same name until 1981. But early on, when he was just immersing himself in the world of Brecht’s outsider, he painted two corresponding pieces: first, a relief titled Baals Frauen (Baal’s Women), an expressive exploration of the mistreated lovers of the antihero. Deformed faces are only vaguely recognisable, while thickly applied paints almost tempt one to touch the surface.

A few years later, a second painting: Now it is the protagonist himself that Cerha captures on the wood foundation. With a similar strength of expression, the crushing personality traits of Brecht’s character are made clear. In his notes from 1968, Cerha writes:

I painted a Baal head, on wood. He stares at the viewer from the front, with a low black forehead, money in his sticky hair, large nails digging purple skies into his temples, the screws of his fangs waiting to be let go and to take life, the gears of his nipples grinding forward on invisible insatiable drive shafts, blood-red juice oozing from the crooked corners of the mouth of his desires …

Friedrich Cerha

Cerha, Notizen zu Baal, AdZ, 000T0079/3

Cerha’s home in Maria Langegg with Baal painting in the background

At the time he was making Baal, Cerha was also busy with another major project: the production of the third act of Alban Berg’s opera Lulu. The elaborate undertaking captured his attention for a total of 14 years, from 1962 to 1978, essentially—and one could almost say logically—rubbing off on his painted works. Berg’s opera came on the heels of the tragedies Erdgeist and Die Büchse der Pandora by Franz Wedekind, and tells about the rise and fall of a seductive protagonist. She ends as a poor prostitute on the streets of London, where she is murdered by her final customer, Jack the Ripper. A 1973 assemblage by Cerha bears the name of this killer. Two large objects, a leather glove and an iron chain with a long handle—the alleged tools of the murderer—are glued to the suggestive painting. The narrative, however, is only hinted at.

Jack the Ripper, 1973, mixed media on wood, 40 x 32.5 cm

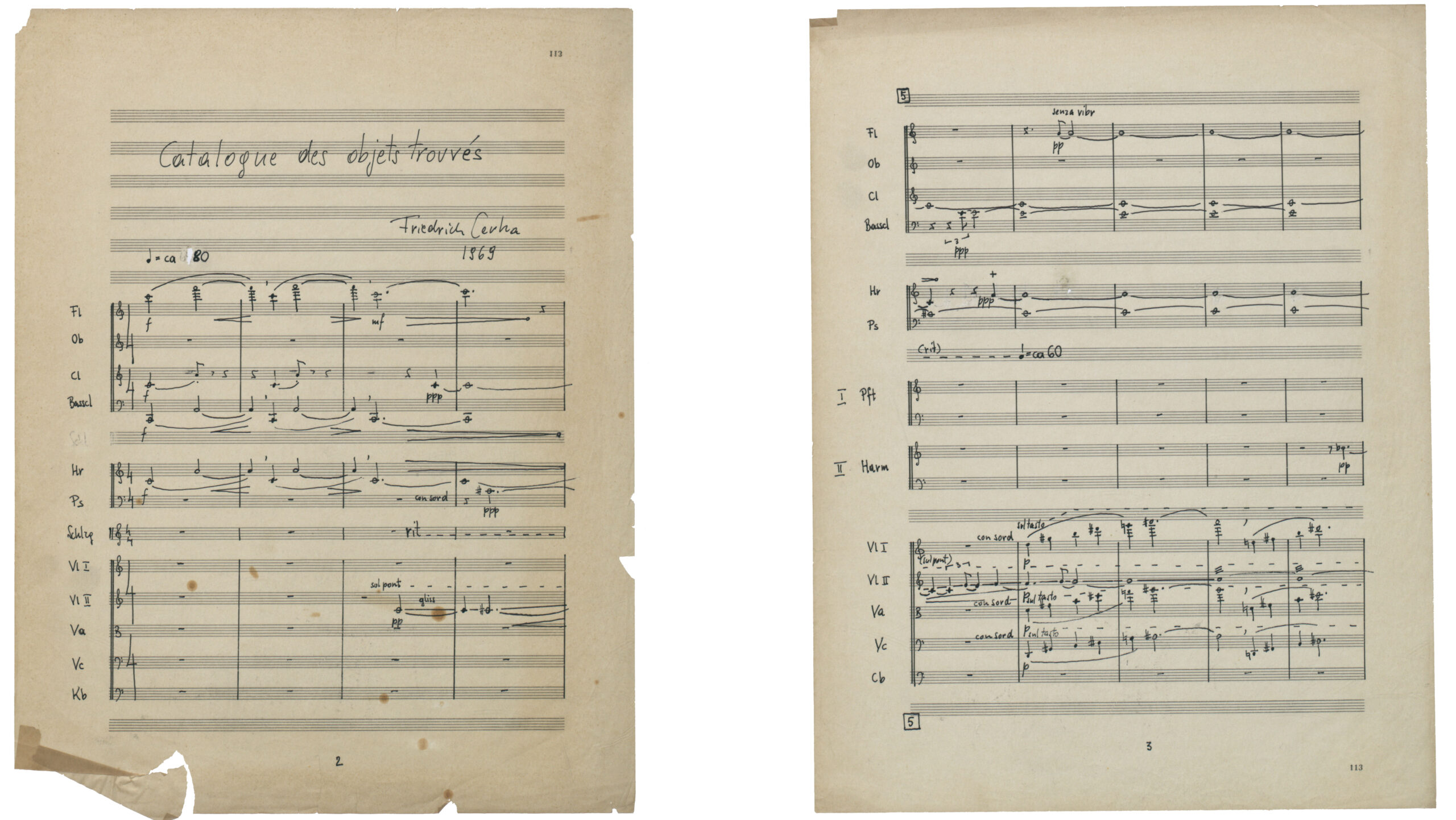

The connection between music and art is much more evident in an ensemble piece Cerha composed in 1969 titled Catalogue des objets trouvés, in reference to the found objects that Cerha regularly integrated into his paintings starting in the 1960s. He uses the term that emerged through the Dada movement during the early twentieth century. French artist Marcel Duchamp’s objets trouvés (also: readymades) are particularly well-known. He even exhibited a standard urinal (Fountain, 1917) as a work of art, sparking a heated debate about the definition of art itself.

Cerha’s Catalogue implements musically what is presented visually by his assemblages: The presentation of found materials and their interaction with wholly different materials. On the topic of the transfer of his painting methods to his music, Cerha states:

I was trying—as with my paintings—to see “objects” in musical material of stylistically different provenance and to “compose” with them. This is based upon a special and earnest attentiveness to “things”, the things we come across, the things we live with—a gentle affection, a love for the objects. This creates a different relationship: not one of using something and carelessly casting it aside when it is no longer needed, but rather allowing a confidential closeness to develop.

Friedrich Cerha

Joachim Diedrichs: Friedrich Cerha. Werkeinführungen, Quellen, Dokumente, Vienna 2018, p. 110

“Each of the musical objects in the piece,” says the composer, “was equally important to me.” And this is how things that did not originally belong together come together: Stylistic allusions to the Vienna School (especially Anton Webern), to Erik Satie (with almost literal quotations), and to his own past compositions stand side by side with other imaginatively discovered musical objects.

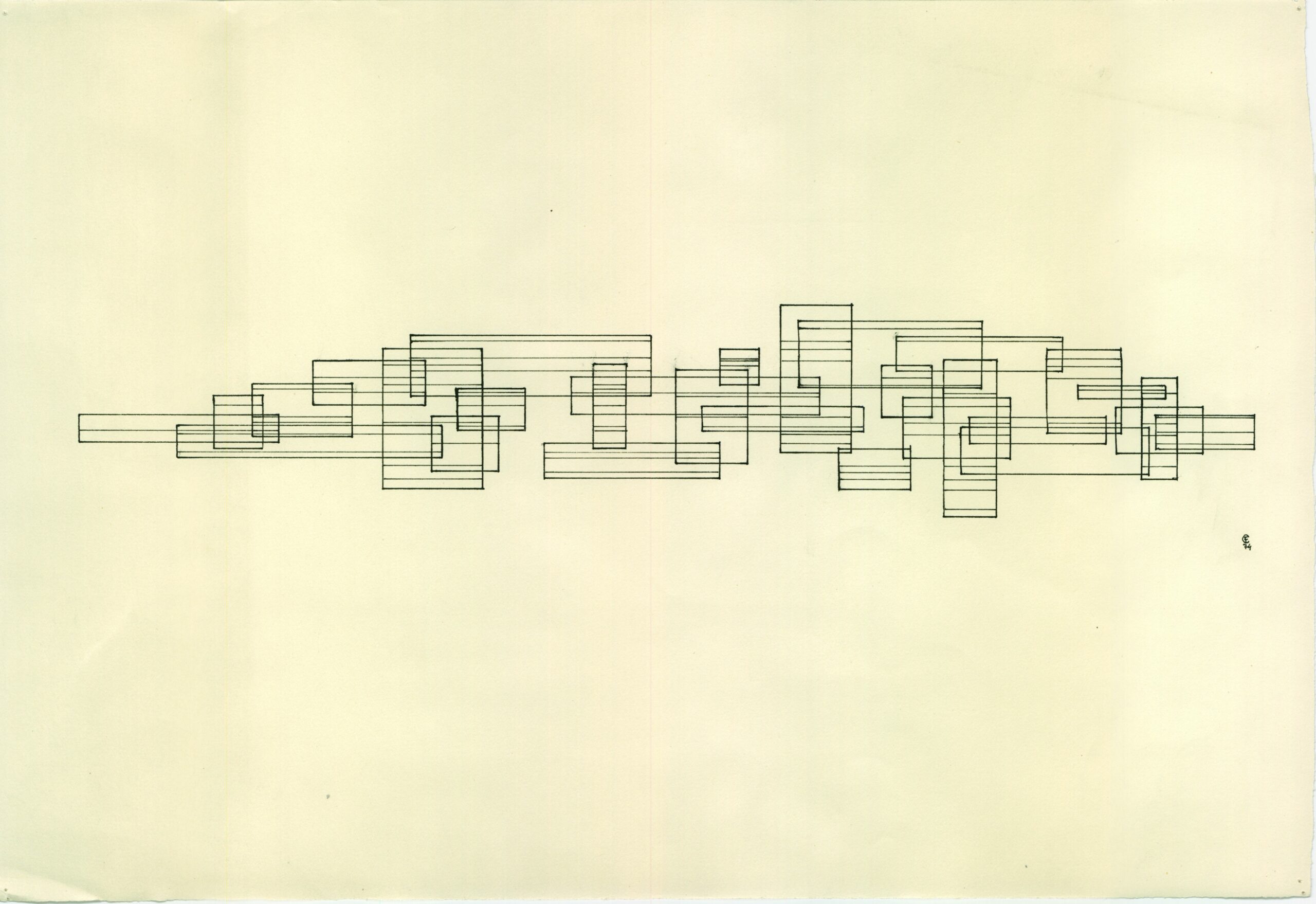

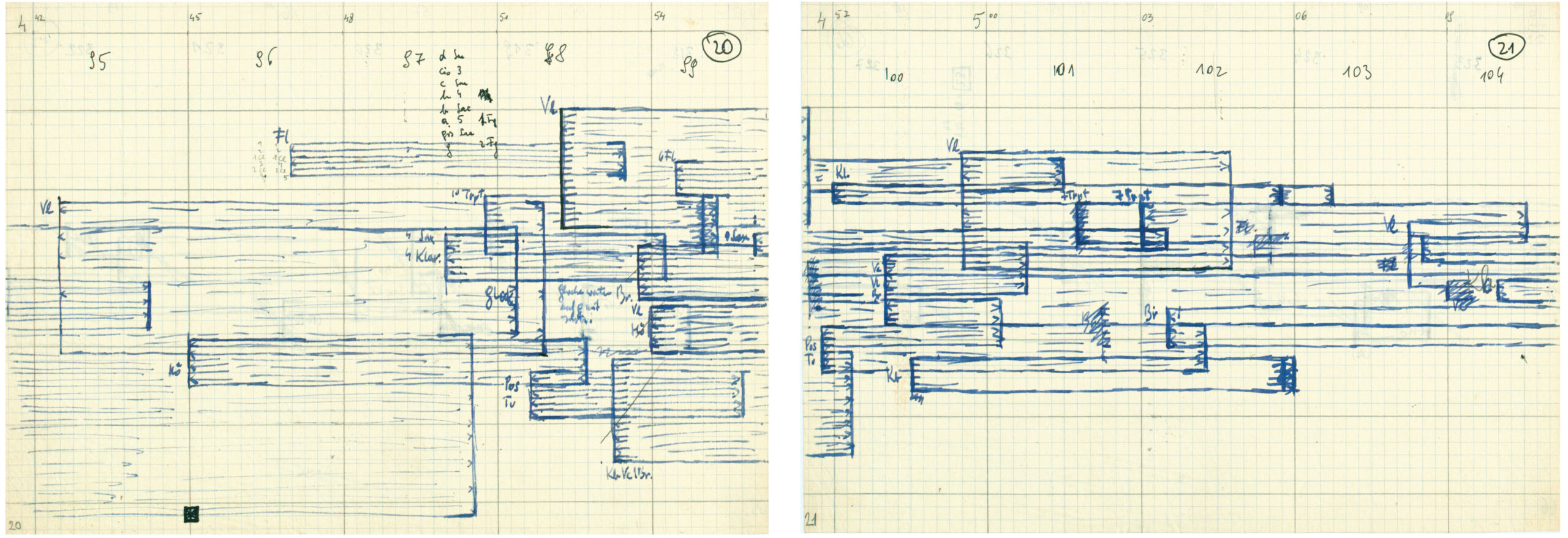

Cerha, Catalogue des objets trouvés, autograph, AdZ, 00000074/101f.

Cerha, Catalogue des objets trouvés, Begin

Ensemble “die reihe”, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha

Cerha, drawing based on a musical idea, 1974

Cerha, Fasce, sketches, pp. 20 and 21, 1959