Monumentum

Do you know that trees talk?

Monumentum

Kreuzweg

Exercises

Baal

A grove of trees in the Central Siberian Botanical Garden

Trees are social beings. If you look up into a canopy of leaves, you will see curious gaps between the treetops in certain places, a phenomenon called “crown shyness”. This “polite” distancing is a sign of the hidden communication that takes place between these gigantic living beings.

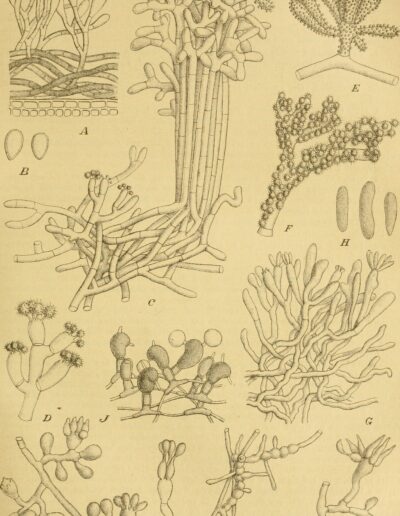

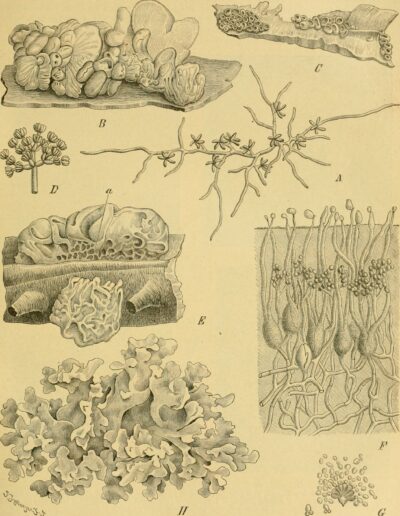

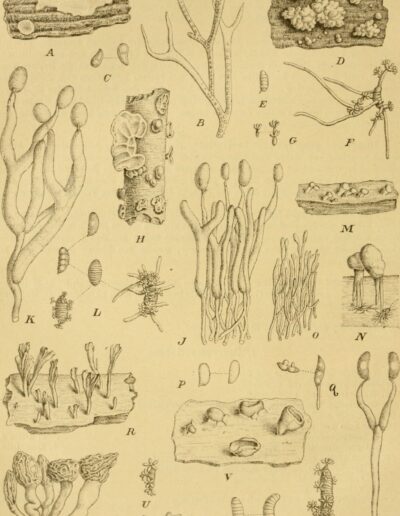

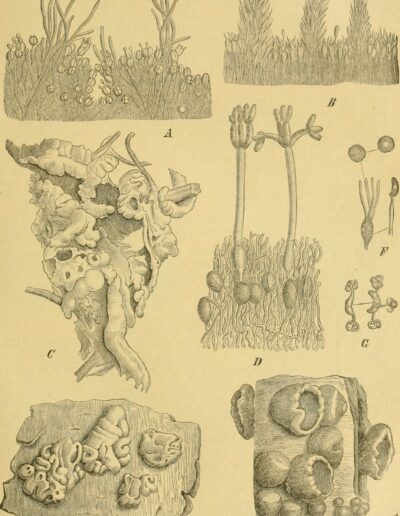

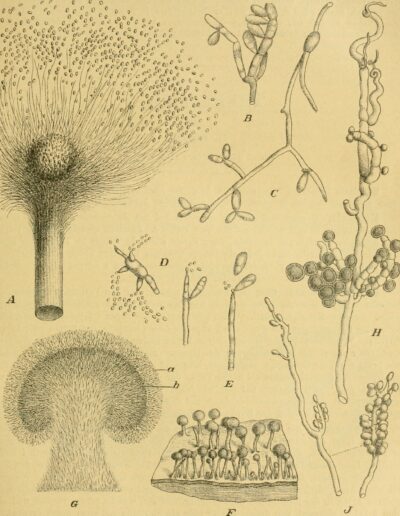

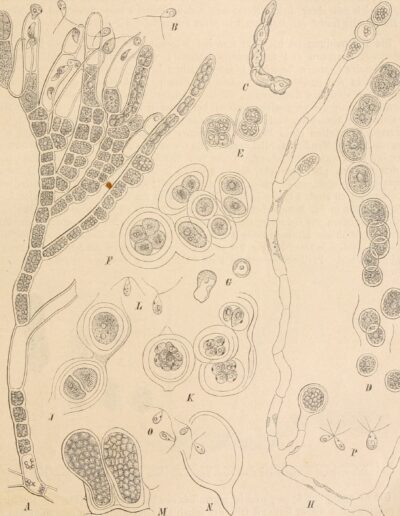

Karl Prantl is the author of one of the most important treatises on the topic of botany: In an unbelievable 23 volumes, Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien unravels the mysteries of our world’s vegetation.

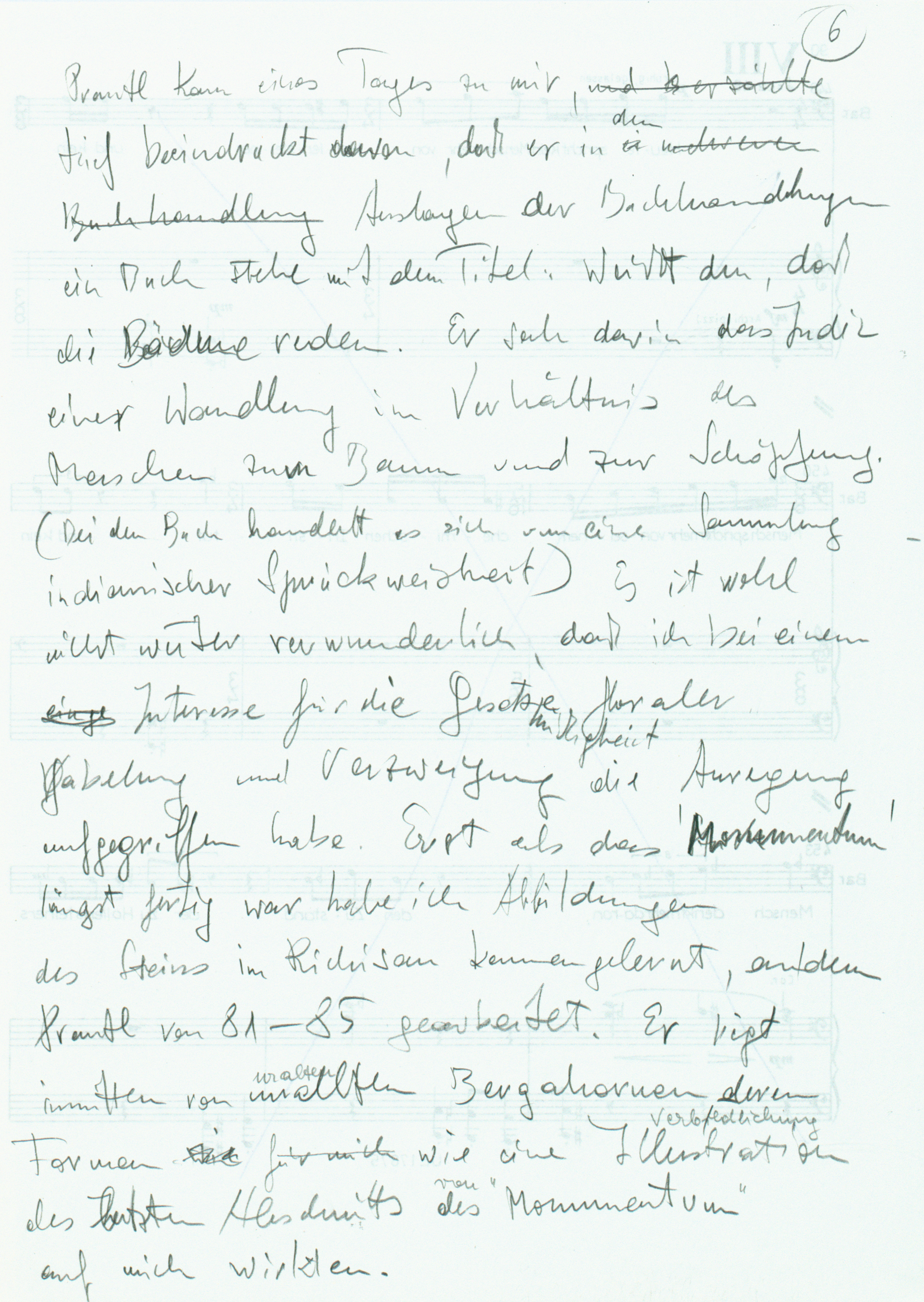

The topic of Prantl’s volumes has little to do with music. And although Karl Prantl is one of the most important artists in Friedrich Cerha’s circle of friends, the name is actually a bit misleading—the author of the immense encyclopaedia of plants merely shares a name with the Austrian sculptor who was a close friend of Cerha. Botanist Karl Anton Eugen Prantl was born 1849 in Munich, while sculptor Karl Prantl came into the world in 1923 in Pöttsching, Austria. Nevertheless, there seems to be a subtle connection here: Both Cerha and his sculptor friend were fascinated by the illustrations of variegated root systems, sprouts, branches, and cells.

Außenansicht

In southern Africa there is a genus of plants that, at first glance, hardly seems like a plant at all. Its botanical name Lithops consists of the Greek words λίθος (Lithos for “stone”) and ὅψις (opsis for “appearance”), revealing much about the look of the bizarre plant. These plants are commonly called “living stones”—not only because of their resemblance to stones, but also because they thrive amongst them, camouflaging themselves to match.

“Living stones” of the genus Lithops karasmontana subsp. Eberlanzii in a rocky landscape

Ragnhild&Neil Crawford / Flickr

The common name seems strange only because stones and plants seem, in many respects, to be opposites. Both are products of nature, yet they are fundamentally different: Hardness and solidity characterize one, elasticity and growth the other—or, to state it even more pointedly: here death, there life. Cerha’s friend Karl Prantl, who devoted his life to making art with stones, would likely disagree with this statement. For him, stones are living beings—something he explains in the opening of the documentary Die Steinspur:

Die Steinspur – Karl Prantl, directed by Robert Neumüller, 2002, 45 min

Prantl’s train of thought provides essential insight into this worldview. There are no opposites between things that exist, only durations: the duration of time on this earth.

Stones are first, then trees, and only then, at some later point, are there humans. And this is true in the other direction as well: I am the one that will pass next. Then the trees that we planted in the garden, the cherry and the nut trees. And then, sometime, the rocks will also pass. Crumbled. Turning to soil.

Karl Prantl

Karl Prantl, acceptance speech for the Grand Austrian State Prize 2008, cited from Andrea Schurian in: Der Standard, 16 November 2008, http://www.andreaschurian.at/der-standard/karl-prantl-kein-kraftemessen-mit-dem-stein/andrea-schurian/

In Prantl’s philosophy, trees become the connecting link between stones—prehistoric beings—and humans, temporary creatures. They combine the durable and the robust with the changeable and active. Stasis and evolution are the two poles, but they are not mutually exclusive. It is precisely this tension that cast a spell over Cerha as a composer. On Monumentum, his first piece dedicated to Prantl, he states:

I find the hecticness and excitement in much music of our time to be senseless. Prantl once said: Art is help. The focussed, simple serenity and power of his stones helped me discover the language of Monumentum. I am thankful for this and gladly pass it on if it can help

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 257

Brücke

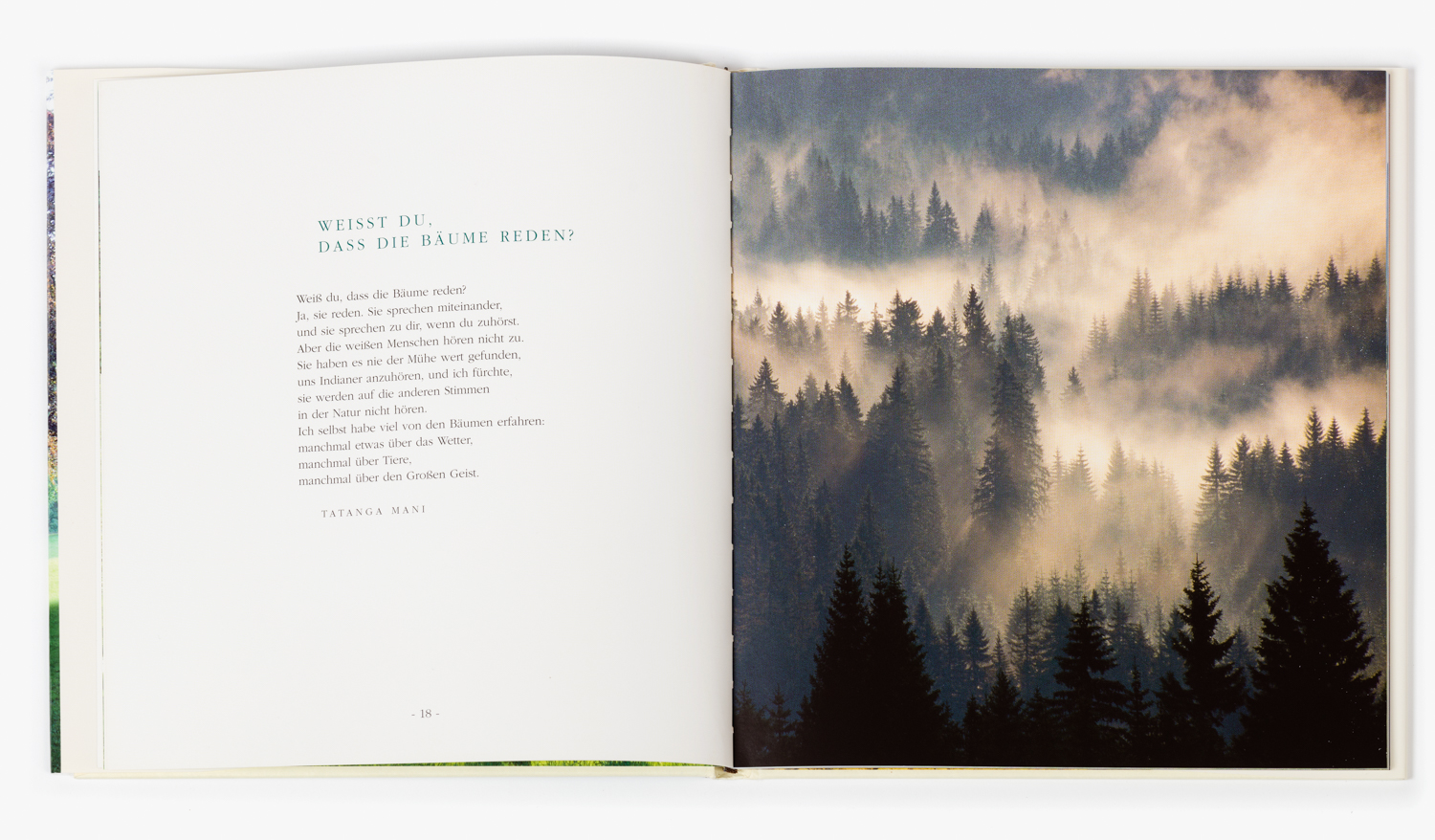

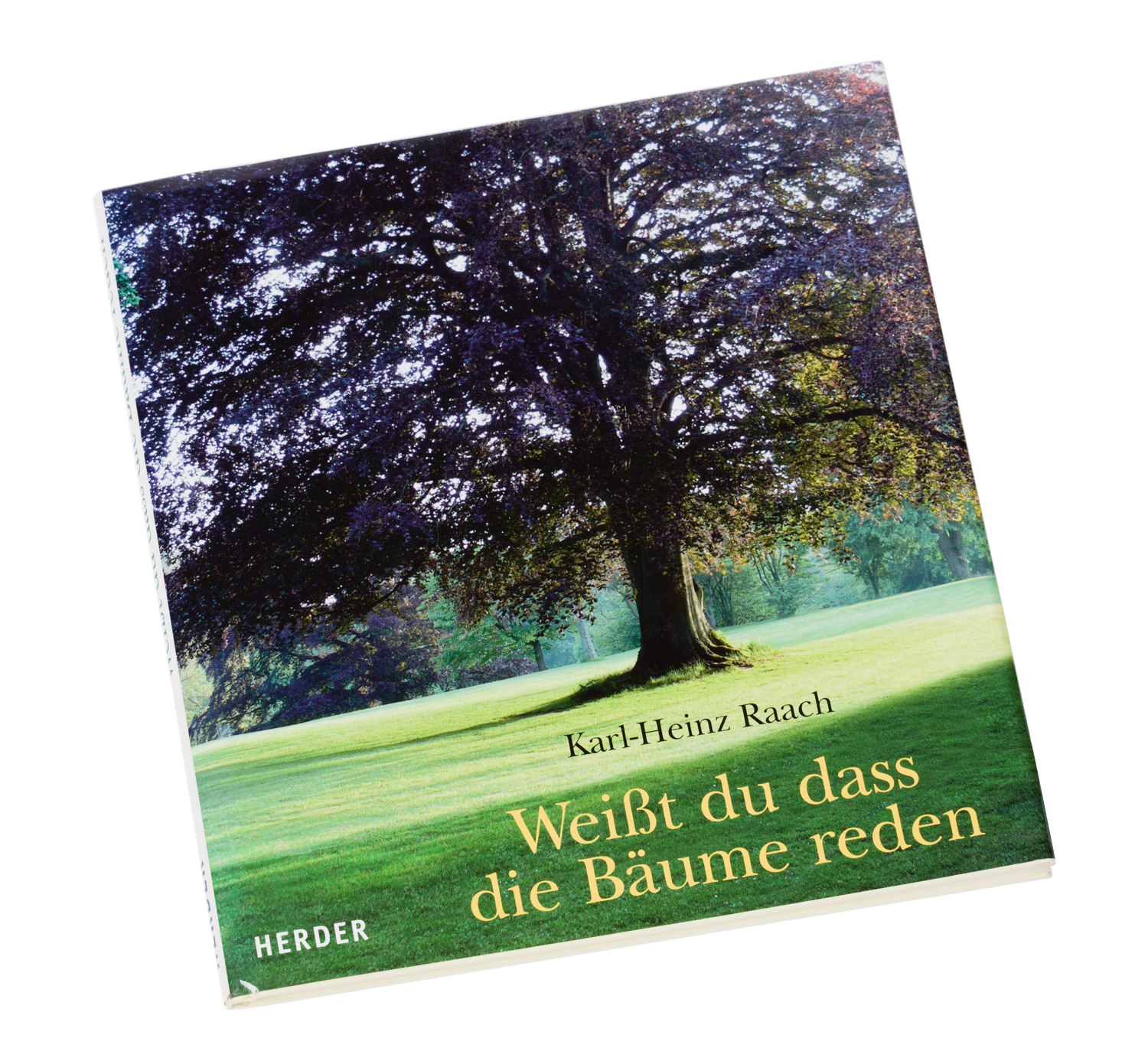

Weißt du, dass die Bäume reden, Friedrich Cerha’s private copy

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

This holistic experiencing of nature also provides a source of deep inspiration for Cerha, both as a person and as an artist. There is an interior point of view that ties into this; just as Prantl’s stones emerge “from a wonder and humility before the beauty and abundance of nature“Marlen Dittmann, speech at the Sparda Bank Award for special achievements in art in public space at the Electoral Palace in Mainz on 3 May 3 2007, https://www.karlprantl.at/biografie, Cerha also sees his approach to a work of art as being humble:

And I think something else unites us with clarity about the significance of analytical instruments: Humility for the incomprehensibility, the inexplicability of creativity, the true work of art. This humility (what an outdated term!) has become rare in an era when works of art are traded as a commodity and in which individuals—especially “professionals”—are often arrogant and calculating about art.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften – ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 256.

Cerha’s interest in botanical root systems leads directly to Monumentum, a piece dedicated to Prantl. One part of the work stands out in particular: the finale. Each section of the nine-part work is dedicated to one of Prantl’s stone sculptures—except for the last, titled “Verzweigungen”. The evocative subtitle “Do you know that trees talk” is an allusion to a book of Indian wisdom published in the 1980s by the Herder publishing house, a copy of which Prantl came across around that time. He told Cerha about the book with great excitement—and it became an inspiration for Cerha in writing Monumentum. Although the idea for the last section initially evolved independently of Prantl’s stones, that idea was ultimately combined with a sculpture in Switzerland:

Only after Monumentum had long been finished did I run across pictures of Prantl’s Stein in Richisau, which he worked on in 1981–1985. The sculpture is situated amidst ancient sycamore maples, the shapes of which are a “visualisation” of the final section of Monumentum

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 257

Innenansicht

Karl Prantl, Der Stein im Richisau, Blautöniger Bahia-Granit (Brasilien), 110 x 165 x 170 cm, Alp im Klönal (Kanton Glarus, Schweiz), 1981-1985

Photos: Rolf Schroeter

In light of the unmistakable anchoring of Prantl’s stones in nearly pristine areas, it is not surprising that studying them led Cerha into musically related fields. As he reflects:

In fact, my observation of Prantl’s archetypal forms stimulated my intention to increasingly include elements from this period in my field of vision, something which would have an audible impact on some pieces in the 1990s.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 258

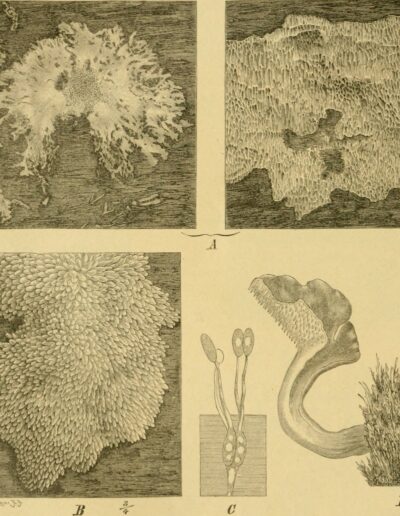

Austrian photographer Lukas Dostal captures the subtle structures, patterns, and imaginative inscriptions of Prantl’s sculptural work:

Karl Prantl, Stein für Friedrich Cerha, Krastaler Marmor, 130 x 190 x 870 cm, Pöttschinger Feld, 1984-1987

Lukas Dostal

www.lukasdostal.at

The equivalent of Prantl’s precision and thoroughness in working the material is, with Cerha, a love for fine and meticulously developed aural structures. The shadowy contours of nested intricacies repeatedly appear throughout the varied sections of Monumentum, mostly in the strings, creating a musical image of vine-like vegetation slowly growing in one direction. The first of the four meditations—the interludes to the five main sections—illustrates this sound concept perfectly. Network-like vocal interweavings alternate with brief rests.

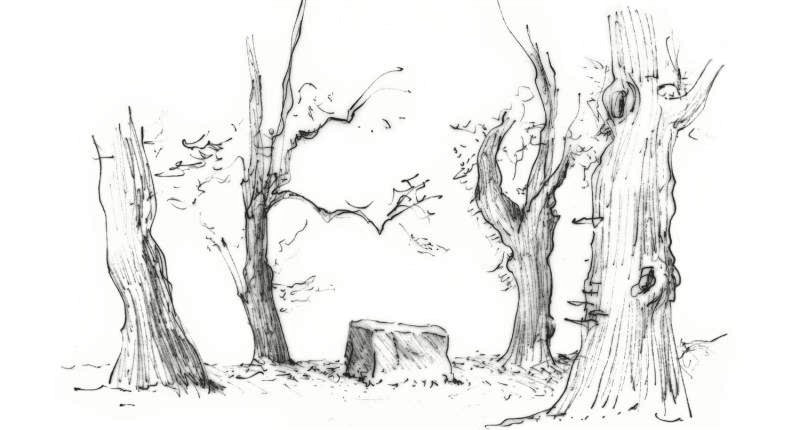

Jean-Daniel Wyss, sketch of Prantl’s Stein in Richisau

Bildquelle: Gasthaus Richisau, mit freundlicher Genehmigung

Cerha, Monumentum, „Meditation I" (Ausschnitt)

RSO Wien, Ltg. Dennis Russell Davies, Produktion Kairos 2010

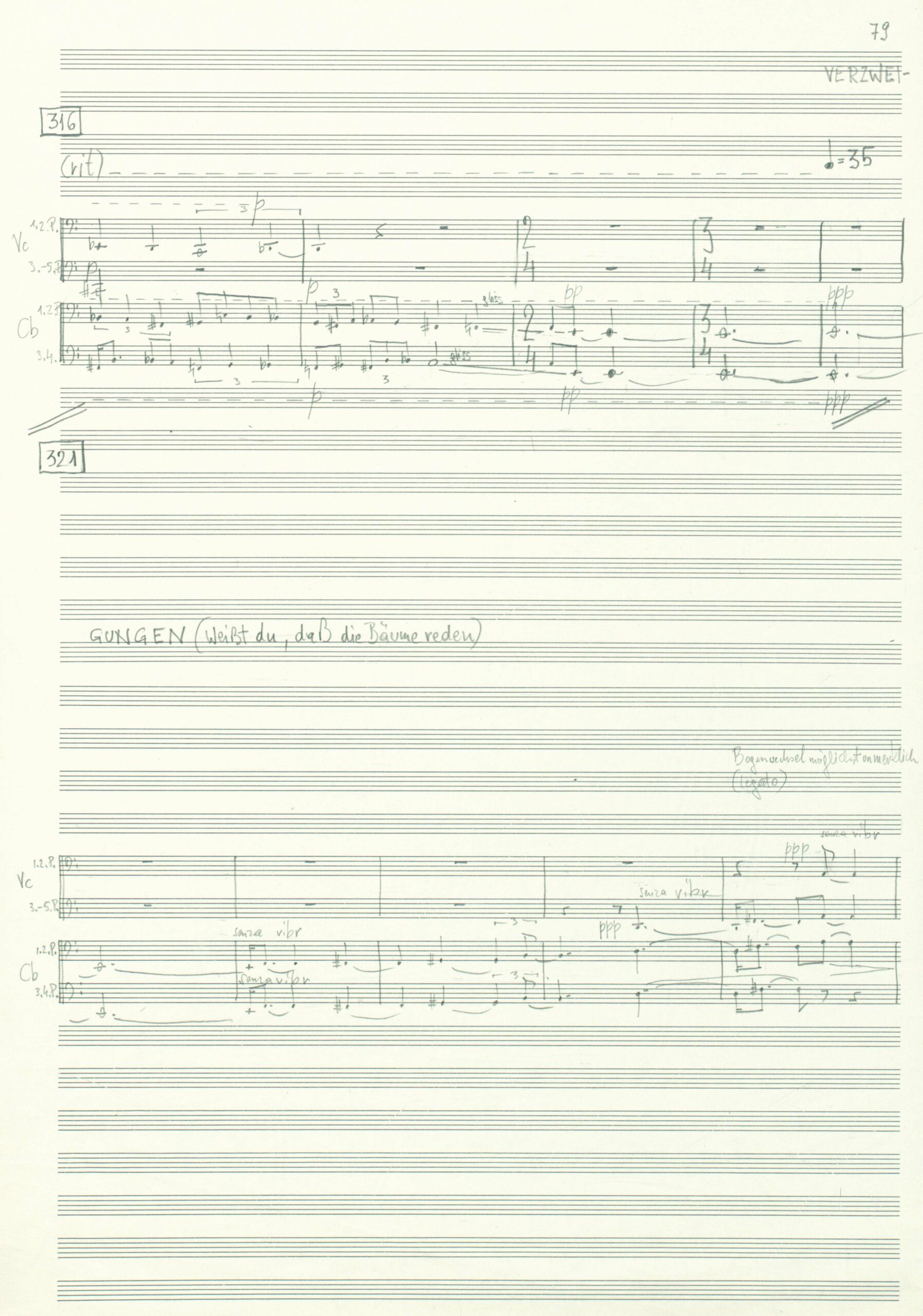

These “tonal root systems” are only momentarily hinted at in the first meditation before they disappear, returning at various points in the composition. Sometimes they stand alone, sometimes they extend underground through a field—as in Kreuzweg—or counteract massive blocks of sound that are in turn reminiscent of Prantl’s sculptures—as in Zeichen. However, this botanical music concept truly culminates in Verzweigungen. Meticulousness and elaboration are elevated to become the sole focus, causing a music of almost endless growth to emerge.

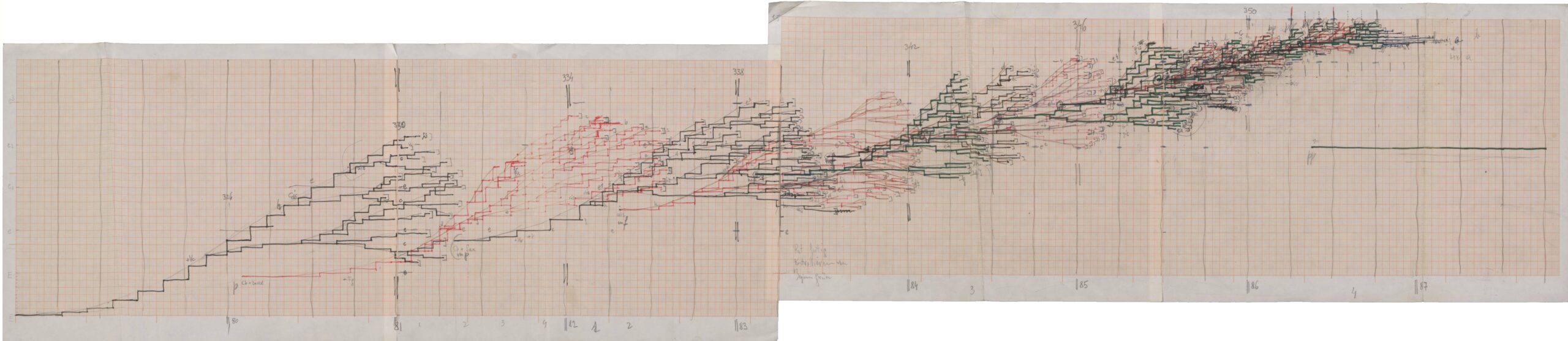

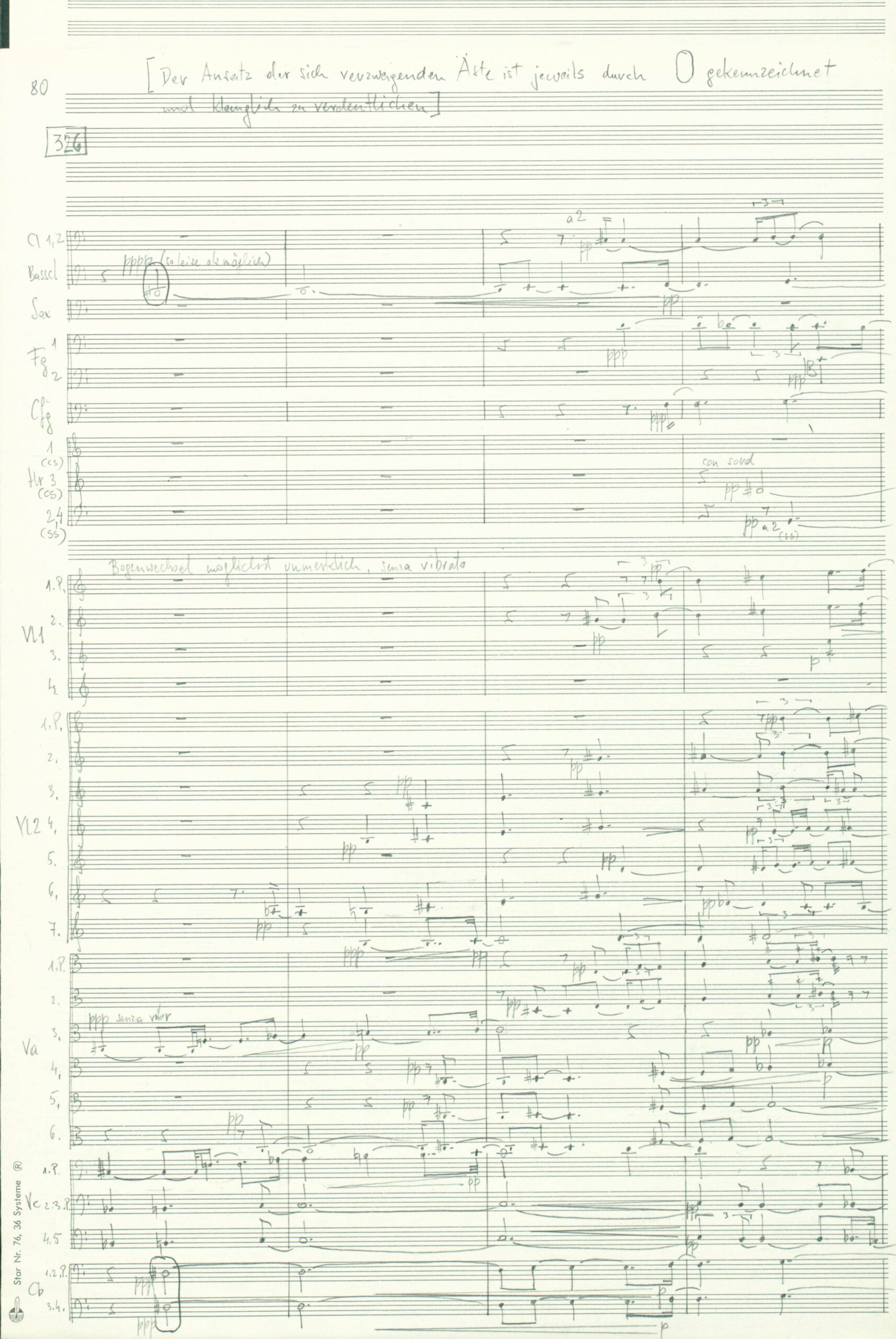

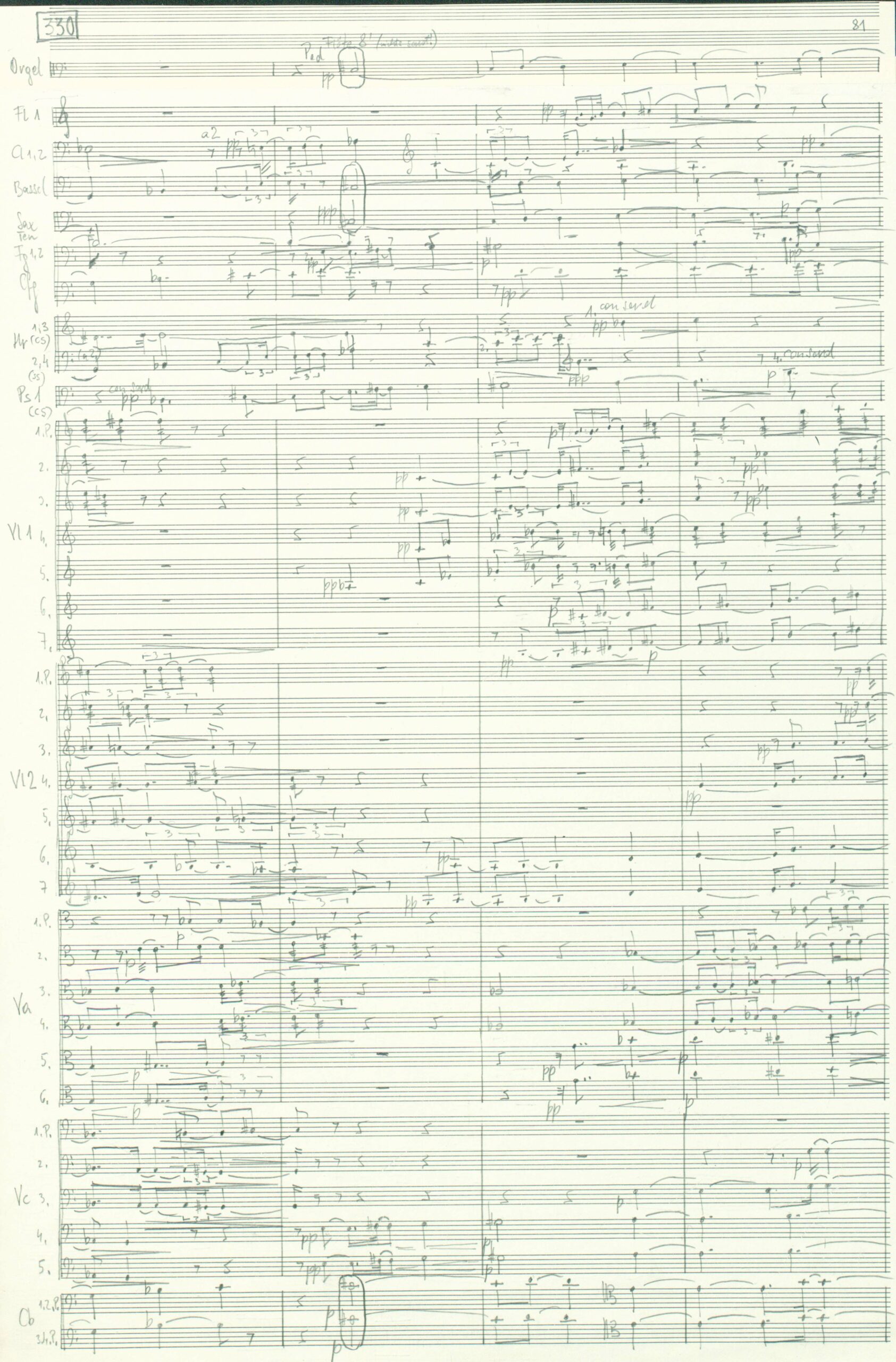

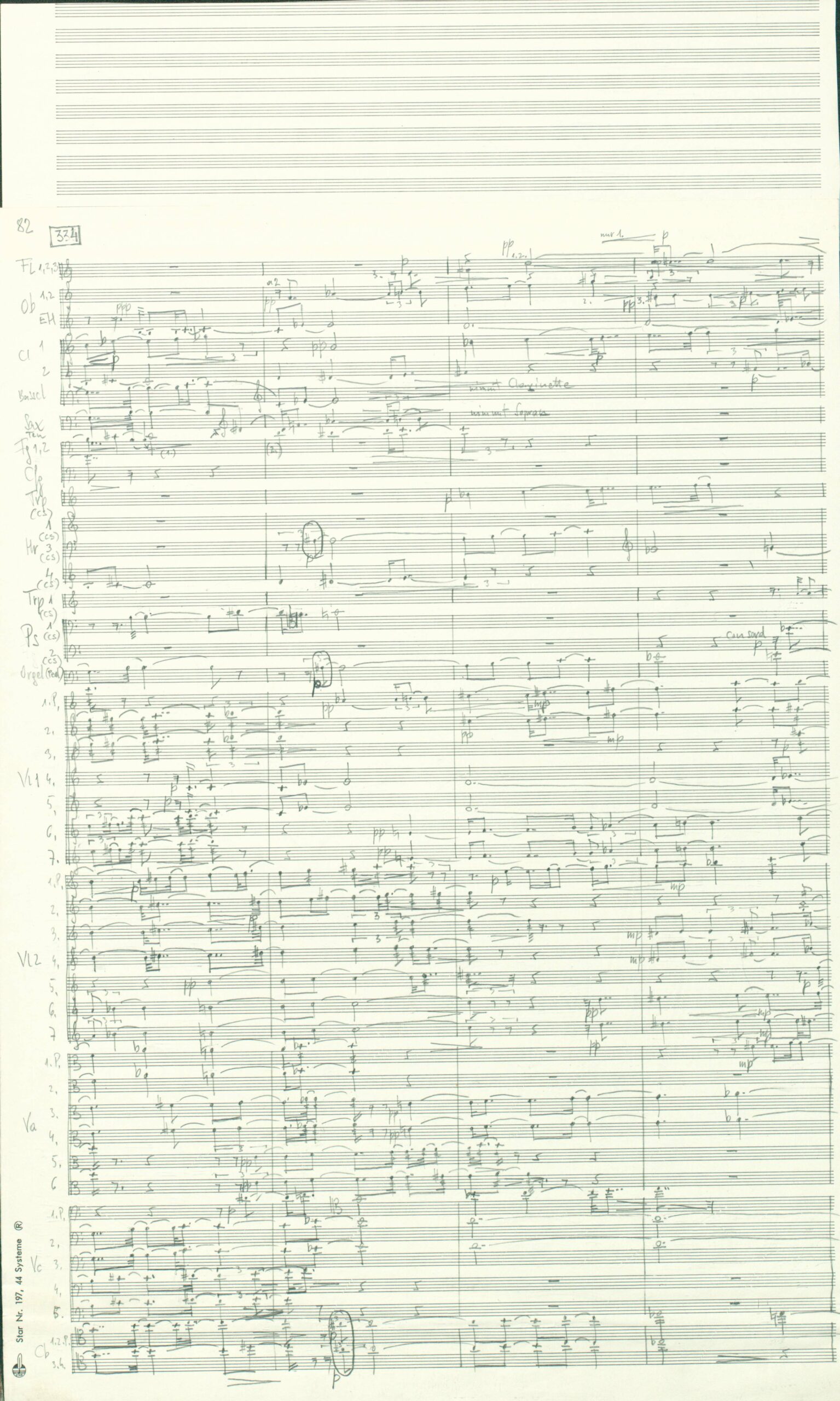

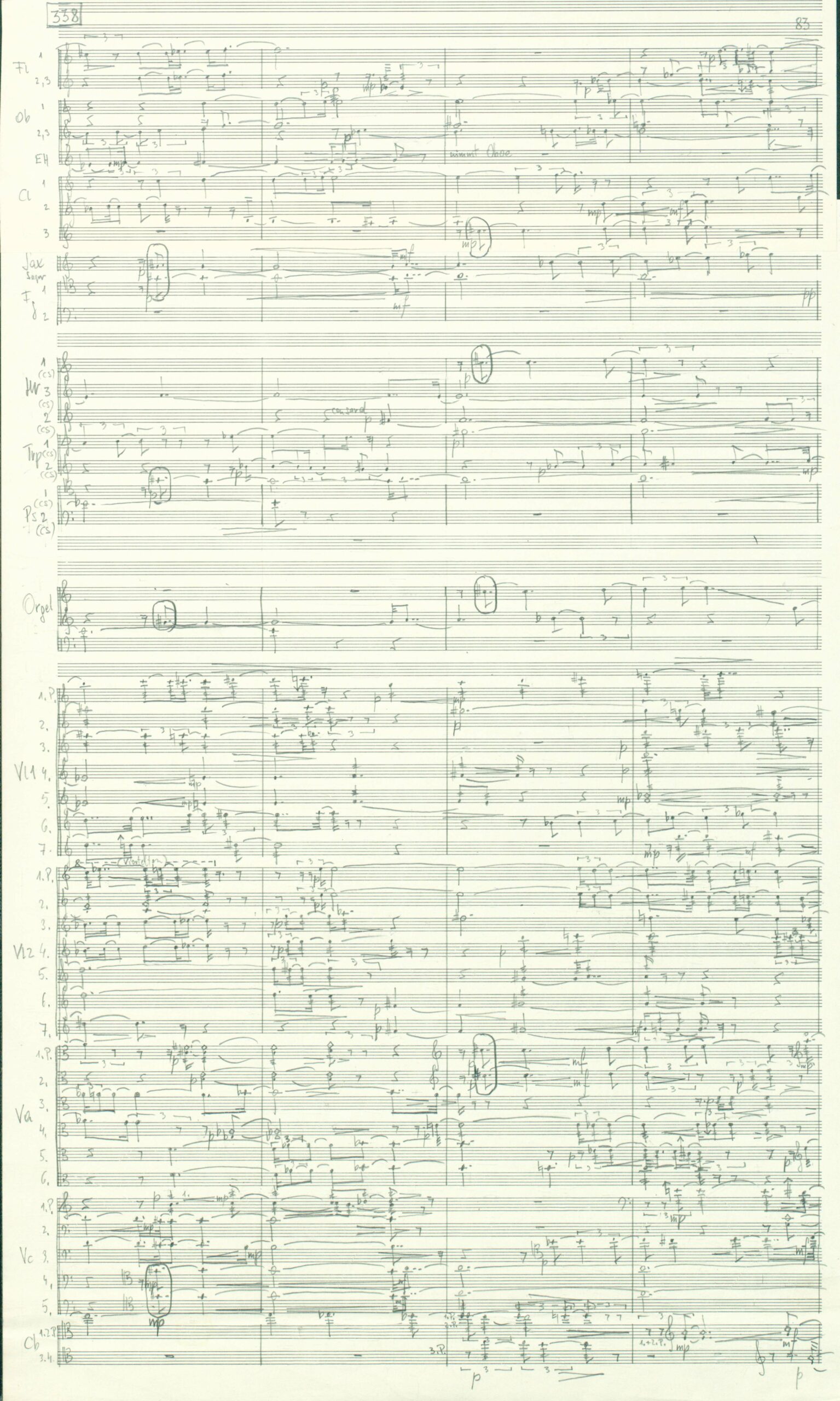

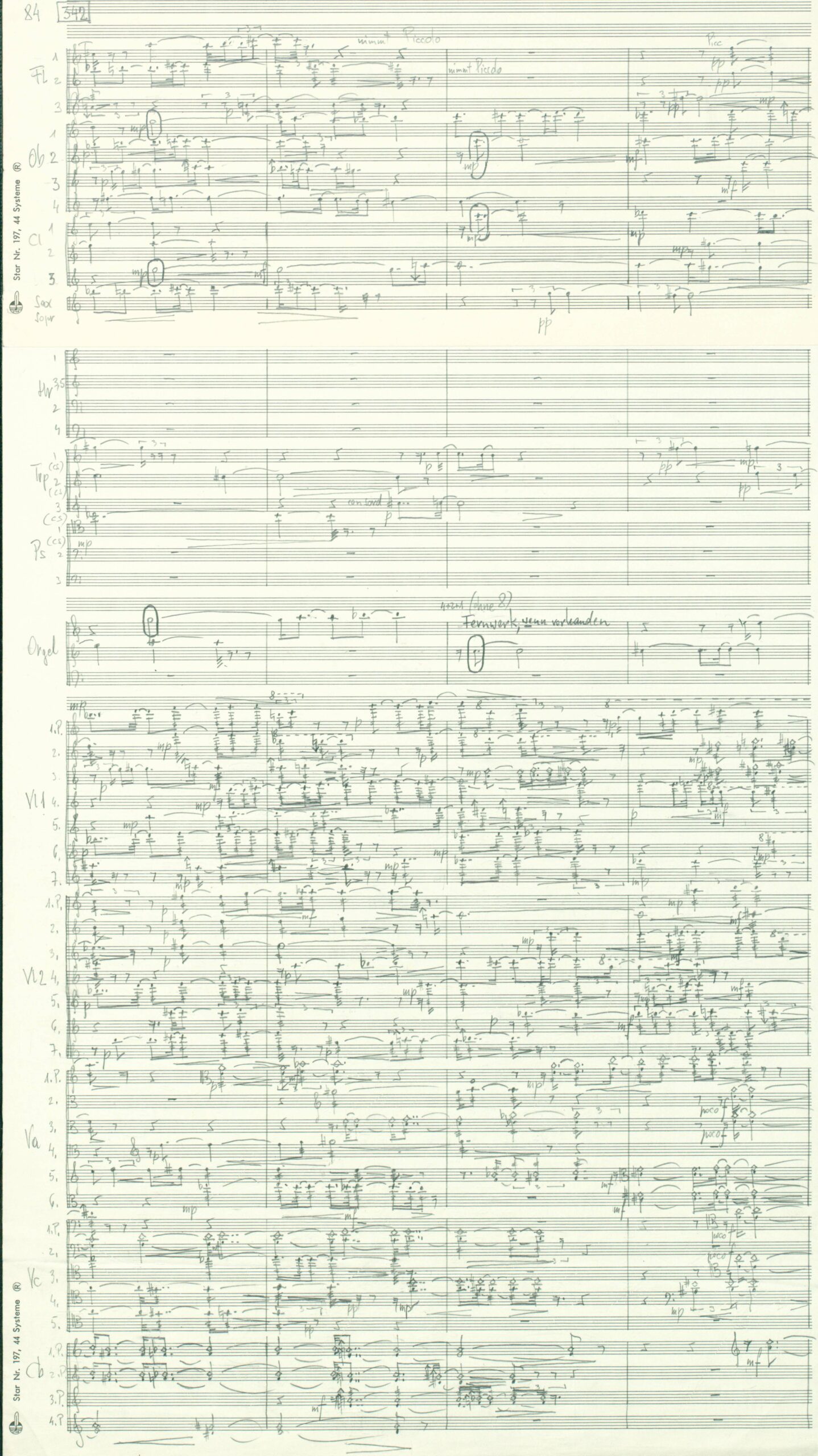

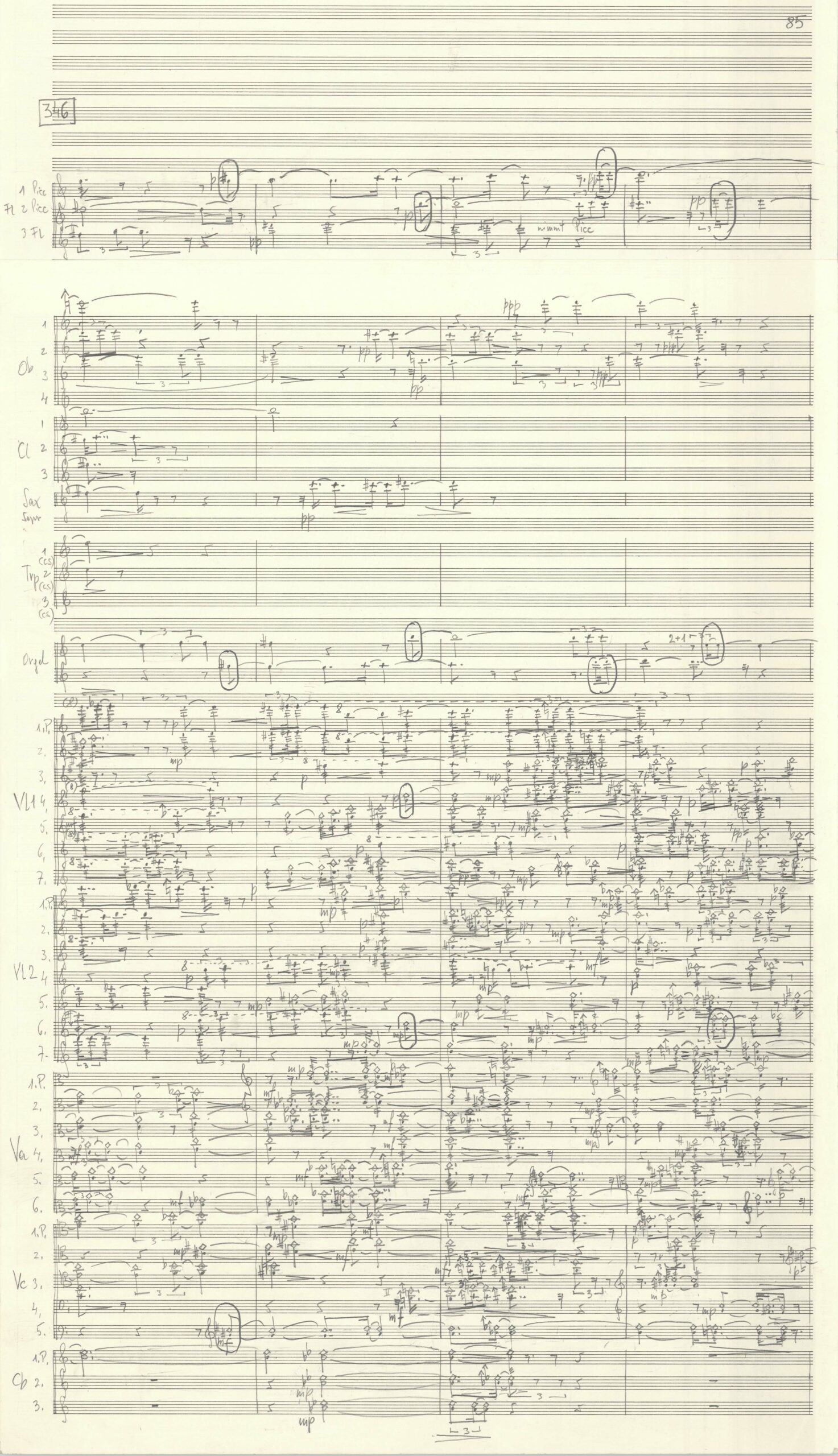

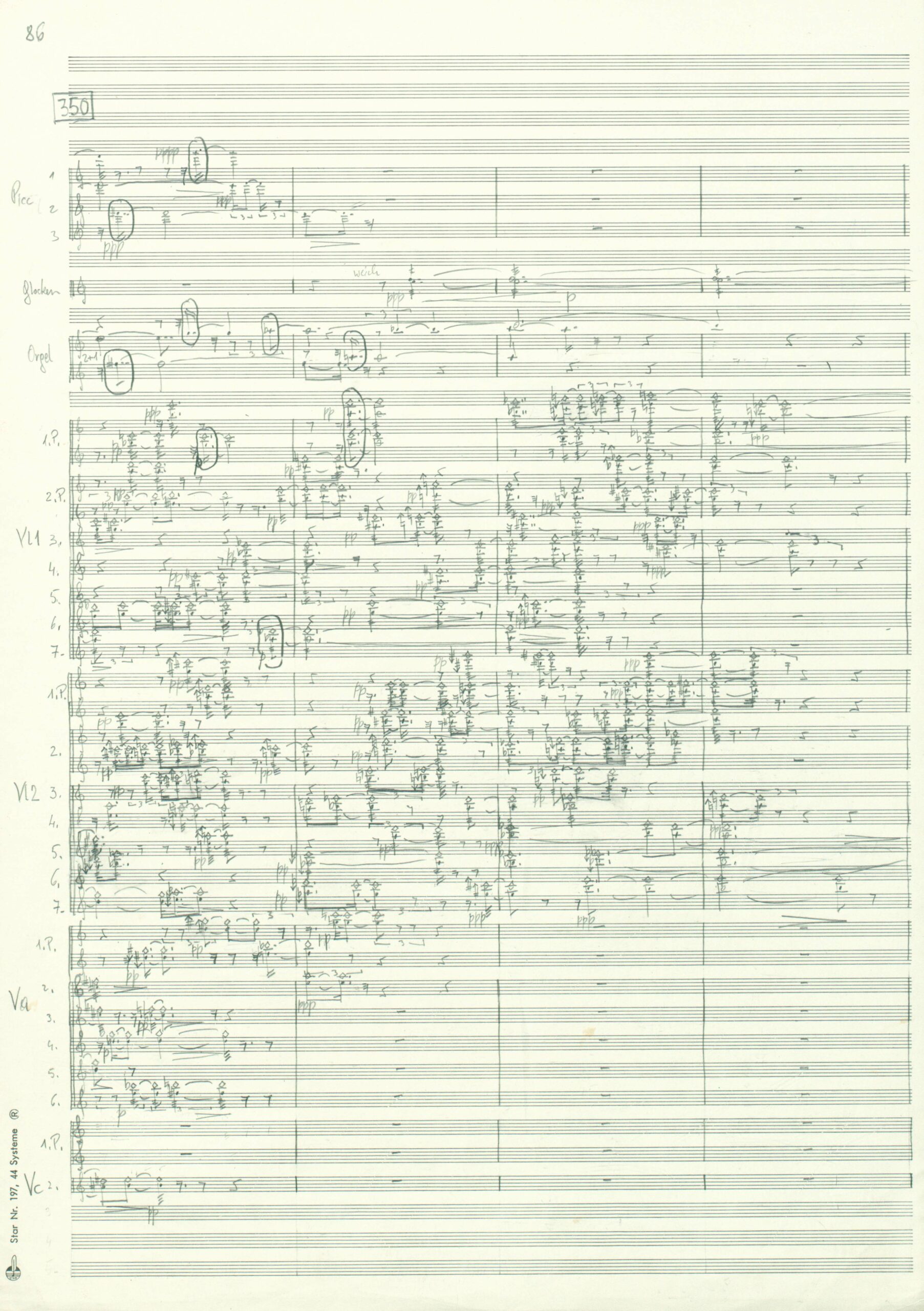

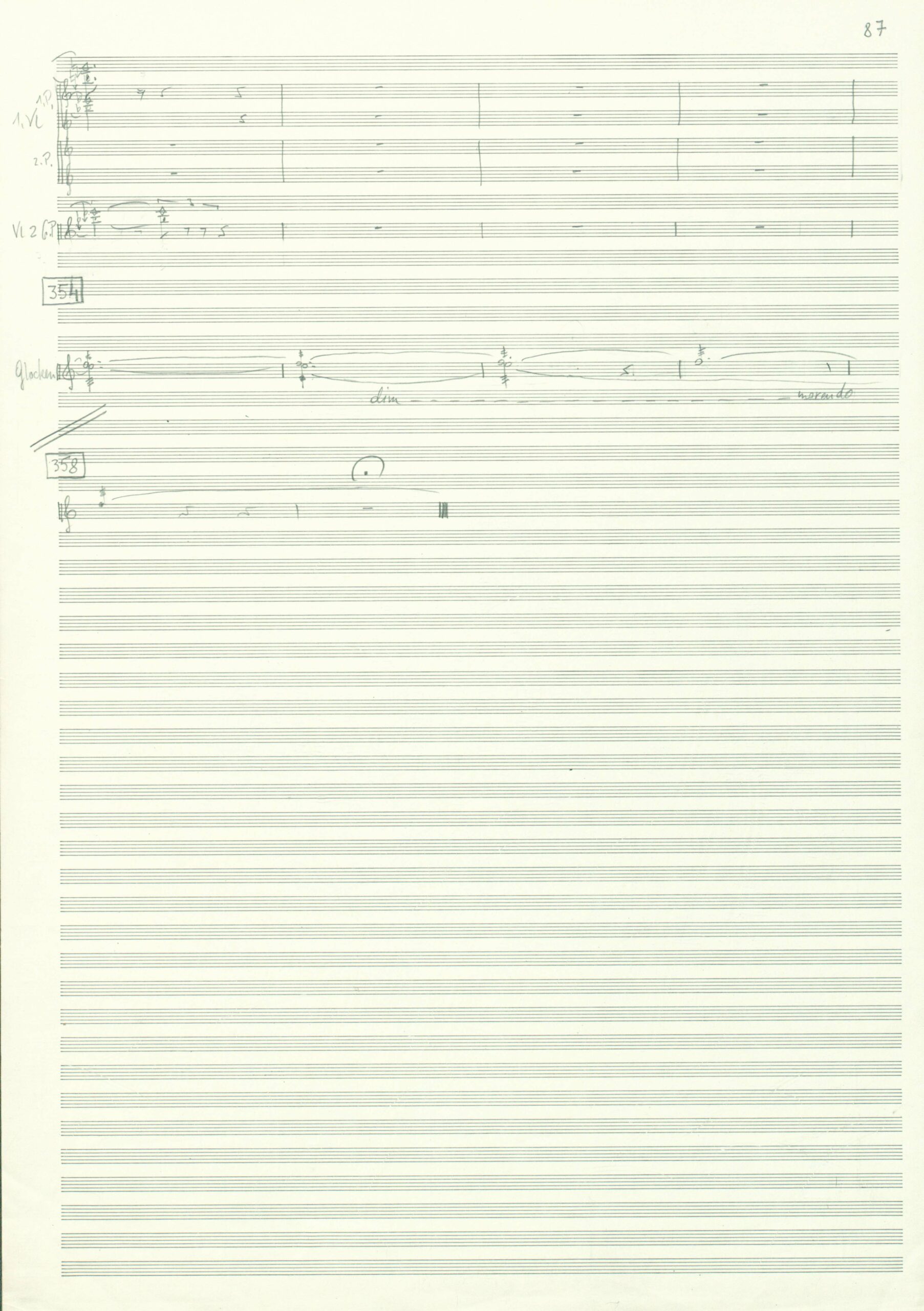

The music created in Verzweigungen is simple yet complex—simple as a whole and in its “tangible” development, complicated in its details, phrasing, and layering. Probably the most impressive testimony to this contradiction is a sketch Cerha drew to document the entire course of the approximately five-minute finale on only four sheets of paper. The music is not written using conventional notes—instead, the notation is almost architectural, with the lines of graph paper serving as the foundation for the graphically astounding work. It is not the first time Cerha uses this system—earlier pieces, such as the gigantic Fasce, were also sketched on paper in this way, especially when the composer needed to create particularly dense and layered vocal fabrics. For Verzweigungen, Cerha uses the tiny squares of the paper like note cells: One square is a whole tone, half is a semi-tone—an octave is made up of six “stacked” squares. The 36 boxes arranged vertically on a page provide an extremely large tonal range of six octaves, which Cerha takes full advantage of. Placed next to each other, the sketches illustrate the evolution of the music at a glance.

Cerha, sketch of Verzweigungen on graph paper, ca. 1988

Continuing the idea of branching, more and more sound forms interlock, overlap, and densify. In order to distinguish these complexes in the sketch, Cerha subdivides the design with different colours. Black, red, dark green, and blue lines shape the page. The different colours sometimes indicate a later orchestration—and in many places Cerha notes which instruments should be used where.

While the fundamental concept of the piece can be understood directly from the sketch—including some of the details—this is not true of the later formal score. The transfer of the boldly branching sound structure to conventional notation illustrates the pragmatism of conductor Cerha, who uses this type of graphic notation extremely sparingly—as appealing to the eye as it may be. The transformation to a traditional five-line system should not be seen as a sombre compromise. On the contrary: With it, Cerha generates the opportunity to grow his musical “plant”, to coax the developing buds into full bloom.

Ultimately, the final version loses nothing of this underlying idea. A review of the final score reveals the different steps along the way, showing how Verzweigungen is finally embedded in the overall complex of Monumentum.