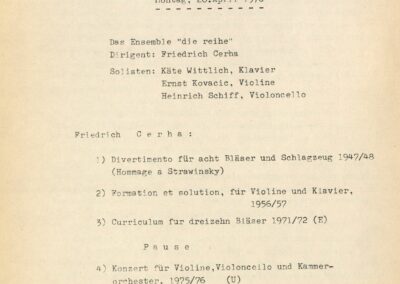

Konzert für Violine,

Violoncello und Orchester

French Clownerie

Klavierstücke für Kinder oder solche, die es werden wollen

Piccola commedia

Pablo Picasso, stage design for the ballet Parade, 1917

French composer Erik Satie was in contact with many great artists during his lifetime, including Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso. In 1916/17, the three worked together on the ballet Parade; Picasso designed the costumes and set. The curtain he created displays a dreamlike scene: a group of performers on one side and a winged horse on the other, creating a thoroughly circus-like atmosphere.

Source: Marc Feldmann/Flickr

It must be love:

Cerha speaks about Erik Satie with greater fascination than for any other composer.

The French composer, who was born in the port city of Honfleur in 1866 and died in Paris in 1925, is one of the most original figures of the emerging modernist era. Satie’s impact extended far beyond the realm of music, for example into multimedia art and the theatre of the absurd. Many important artistic developments of the twentieth century are attributed to him, and he became an icon. But: where admiration grows, contempt is also sown. By no means did everyone, especially in musical circles, approve of his fame. As Cerha put it: “While my love for Webern and Varèse is shared and understood around the world by many of my generation, apart from a few of his and my close friends, I am pretty much alone with my love for Satie. He is stylistically too far-out for most; he is also too simple for many.“Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 241 Cerha’s confessions of love for Satie can also be found in his compositions. The greatest of them is his Konzert für Violine, Violoncello und Orchester.

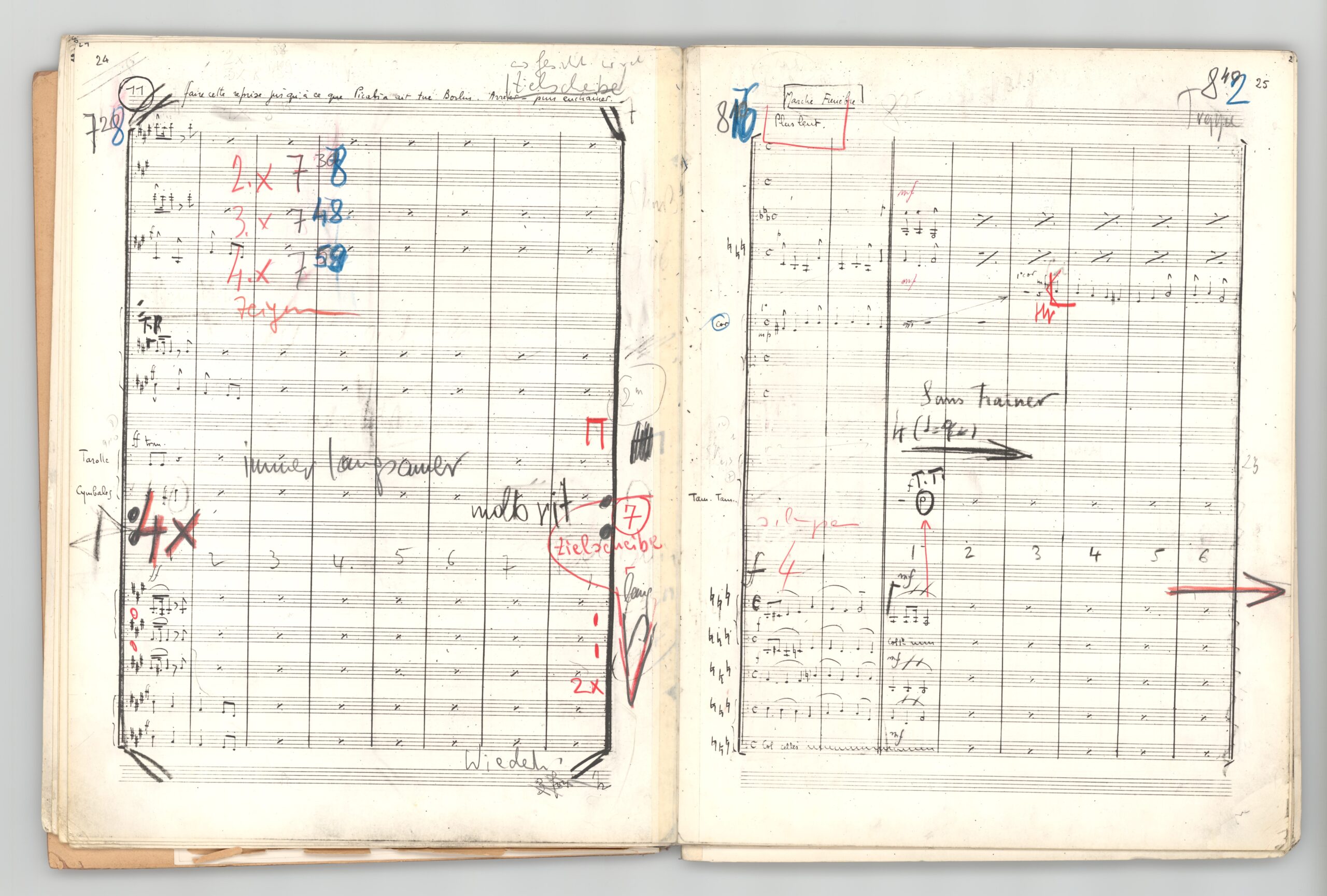

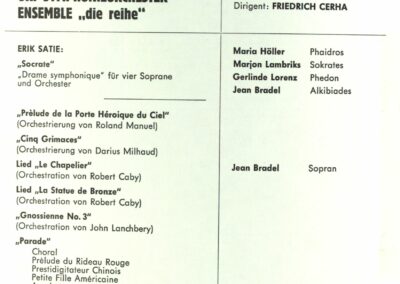

Außenansicht

1958: The two young composers Friedrich Cerha and Kurt Schwertsik returned to Vienna from the Darmstadt Summer Courses for Neue Musik. Dissatisfied with the dearth of space for the avant-garde to grow and flourish in their conservative hometown, they decided to found their own ensemble. “die reihe” aimed to bring the latest music to Vienna, thus closing a gap. However, it was not just current works that didn’t find their place in the concert life of the time. Modernist music of past decades also seemed to have been largely ostracized—art that Cerha and Schwertsik wanted to make audible. Erik Satie was one of the ignored composers. Another composer who caused a sensation in around 1958 was also one of his most ardent supporters: John Cage. In the early 1960s, when “die reihe” was performing works by Cage, among others, the American musician came to Vienna—it is possible that Cage was the origin point of influences that eventually moved the eccentric Frenchman to the centre of attention. Finally, in November 1963, the time had arrived. For the first time, Satie was played in a concert by “die reihe”, including works that are as little-known today as they were back then—such as the song “La Diva de l’Empire”, composed in 1904. Schwertsik even sat down at the piano himself to play Satie’s suite for four hands En habit de cheval together with Gerhard Rühm.

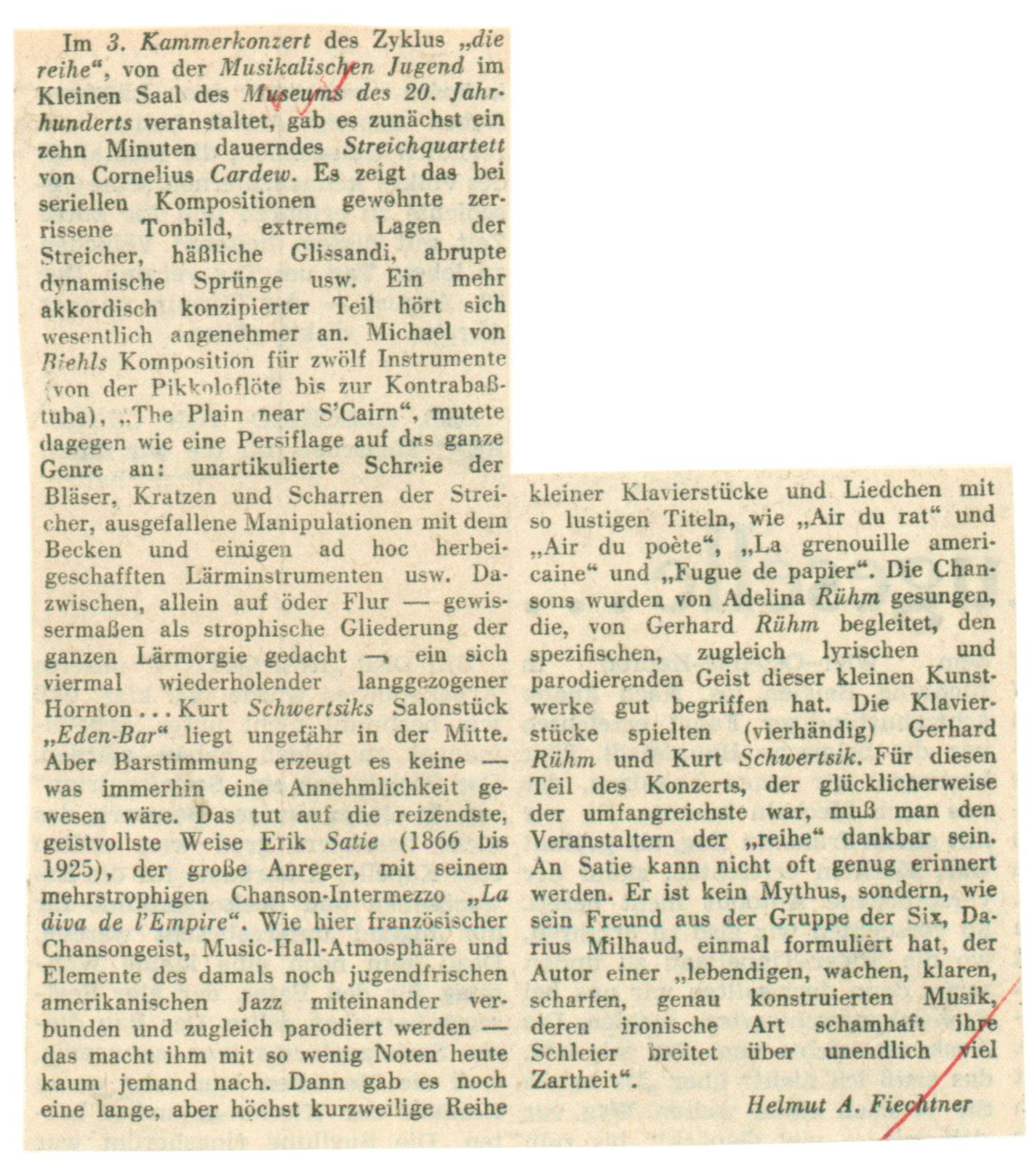

Like almost all the ensemble’s performances, the concert received mixed reviews from the Vienna press. In music history, Satie is classified very differently by various reviewers. Some write about him as an annoying and insubstantial “enfant terrible“Robert Schollum, Nichts gegen einen Studentenjux aber…, Neue Österreichische Tageszeitung, 10Dec1963, AdZ, KRIT0011/139 others celebrate him as a “great inspiration” who “cannot be remembered often enough”.Helmut A. Fiechtner: Untitled, in: Die Furche, 7Dec1963, AdZ, KRIT0011/140 Cerha and Schwertsik took their cue from the latter: Satie was interpreted in many subsequent concerts by “die reihe”, thus becoming a mainstay of the ensemble.

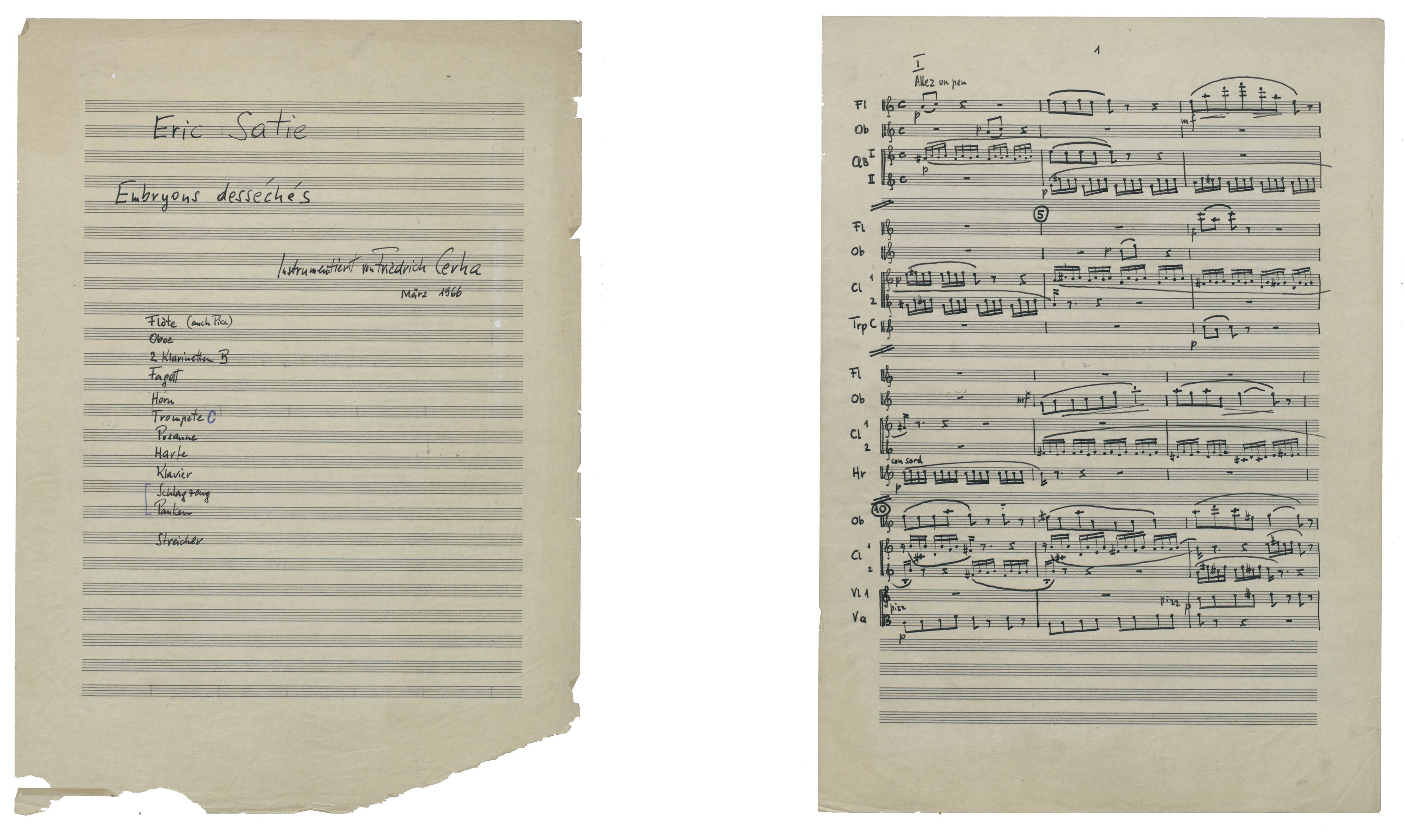

Brücke

Satie’s music is often said to cross boundaries, a viewpoint supported by his “speaking” scores alone. Some of them, such as the piano cycle Sports et divertissements, cross into the realm of visual art—not only with the supplementary illustrations by Charles Martin, but also through the calligraphically artful pages of notation, some of which take up the uniqueness of the accompanying images. Satie also built bridges to poetry—for example, by including original performance notes in his scores, though these remain largely unseen by audiences. Two striking examples: In Embryons desséchés, there is an instruction to enter “like a nightingale with a toothache”, while the pianist for the Trois poèmes d’amour is told to play “with tear-choked fingers”. Both pieces pave the way for Cerha, who arranged and orchestrated the works for an ensemble—one as early as 1966, the other not until 1987. For performances of Embryons desséchés, “die reihe” had a special way of playing. Satie had written narrative descriptions into the score that were intended to be visible only to the musicians. But for concerts, Cerha brought in a narrator who recited the lines, thus making the poetry accessible to all.

Cerha, Embryons desséchés, arrangement of the piano pieces by Satie, handwritten score, 1966, AdZ, 00000071/2-3

Cerha & Satie, Embryons desséchés, 1. Satz

Ensemble „die reihe“, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha, Palais Schönburg, Vienna 1968

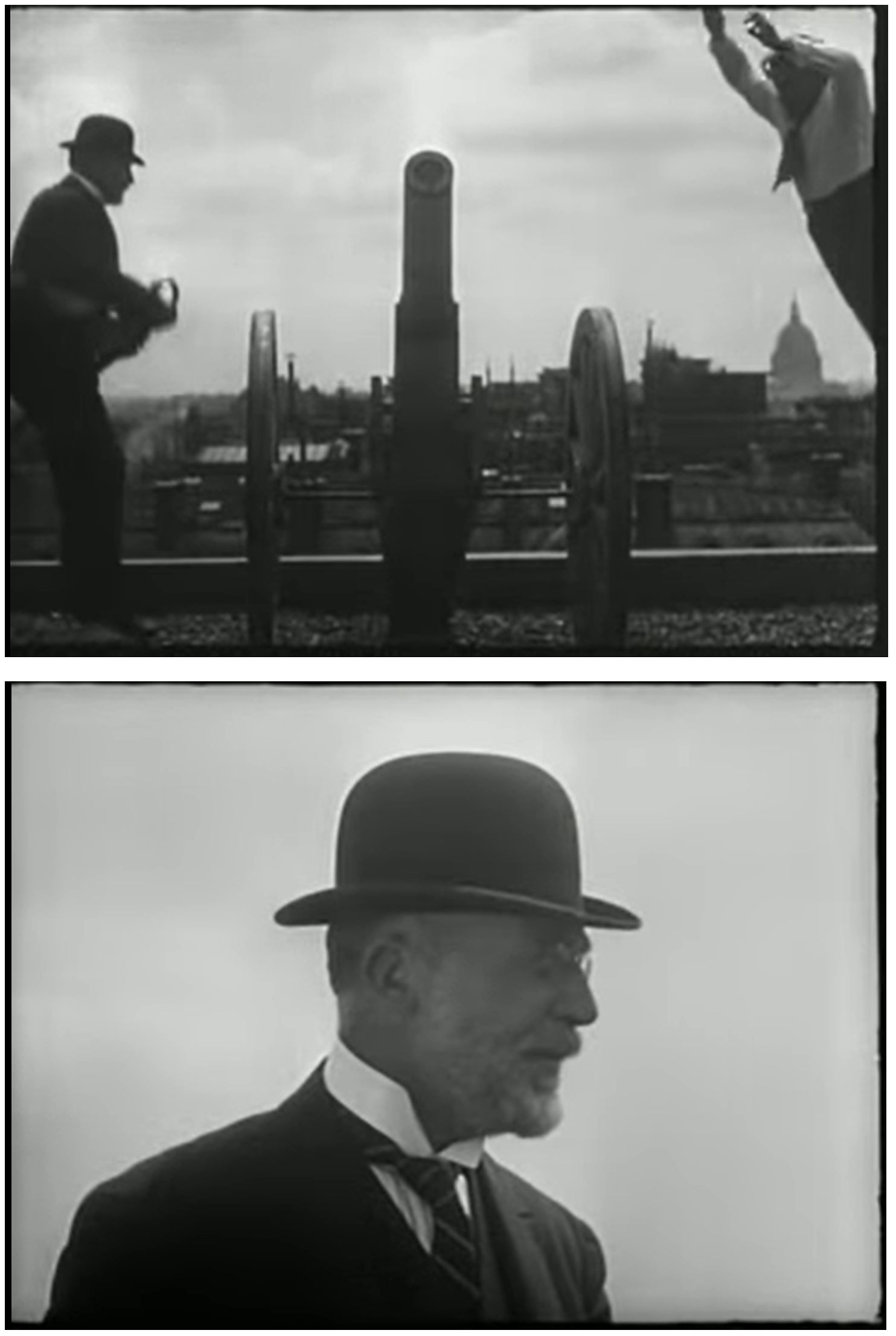

Another medium that interested Satie was film, at the time still a burgeoning form of artistic expression. His work in the field is closely intertwined with the ballet Relâche, which premiered in 1924 at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris. Satie worked together with librettist Francis Picabia, who wanted a film to fill the intermission between the two acts and hired young director René Clair to create one—resulting in the Dadaist short film Entr’acte. Satie not only composed the film music, he can also be seen in the adventurous film. Together with Picabia, he jumps around on a Paris rooftop, in slow motion, with the urban skyline behind him. On several occasions, Cerha and “die reihe” dedicated themselves to Satie’s film music. A concert in April 1964 (40 years after the premiere) was the impetus for this: Original films from the 1920s were being shown on the big screen, with Cerha conducting the music that played in accompaniment. Satie’s piece Cinema, with Clair’s Entr’acte, came first.

In addition to the exciting synthesis of set and music, it was Satie’s approach to composition that captivated Cerha above all. The French artist was further from post-Wagnerian dramatism and tonal painting than almost anyone else of his time. Instead of great, endless arcs, his music was made up of small particles. These were linked to the scenes in a completely new, rather loose way—a technique Satie had also used in his previous ballet Parade (1916/17). Perhaps because Satie had collaborated with Pablo Picasso for that ballet, the music was later sometimes described as Cubist, an unconvincing label considering that Satie followed his own personal, non-ideological path. On the other hand, the dissolution of the overall form into contoured geometric elements, something typical of Cubism, certainly finds parallels in the music. The scores of Relâche and Entr’acte are even more radical when it comes to this: “By filling the four- and eight-bar blocks of the individual dances with small motif pieces with no logical or functional relationship between the elements, Satie prevents large-scale development. Each element remains isolated, a detail, a moment.”Grete Weymeyer, Erik Satie: Bilder und Dokumente, Munich 1992, p. 66

Throughout the 1960s, Cerha was fascinated by Satie’s music for ballet and film, finally mingling traces of it into his own work in 1969. In Catalogue des objets trouvés, he quotes a passage from the Entr’acte almost verbatim, presented as “found” sound material. He vigorously pursued this productive interest in 1975, when a double concerto for violin and violoncello made an appearance on the composing desk.

Innenansicht

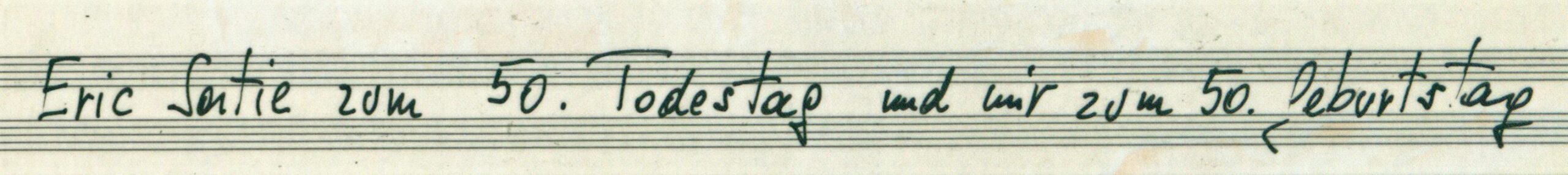

Since the first “die reihe” concerts of Satie’s work, Cerha has been fascinated by his unique and ingenious method of making music out of small, firmly joined building blocks. The interest makes particular sense if you consider Cerha’s own artistic development during the 1960s. Increasingly, musical disparity as an aesthetic category came into focus; breaks and contradictions became more interesting. Cerha explored the interplay of different levels of music extensively in Exercises as well as in the pieces that followed, like Langegger Nachtmusik I. There was a key hidden in Satie’s music that helped overcome the “round” and “satisfied”Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 74 acoustic aesthetics of pure avant-garde. The “precision of his musical character”, explains Cerha, “the sharpness of his drawing, his ability to create complete units from a handful of set pieces” was without comparison.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 241 “In addition, what he did for his era urgently needs to be done today: steering towards bare, chiselled outlines and questions of absolute music, instead of towards an ornamental mannerist fog of sound.” Cerha’s interest in heterogeneity and in Satie’s almost architectural way of composing music inspired Cerha to create a new piece, one with built-in conflict, in the mid-1970s. The dedication of the piece makes “a statement about the task”. In the handwritten score, Cerha wrote:

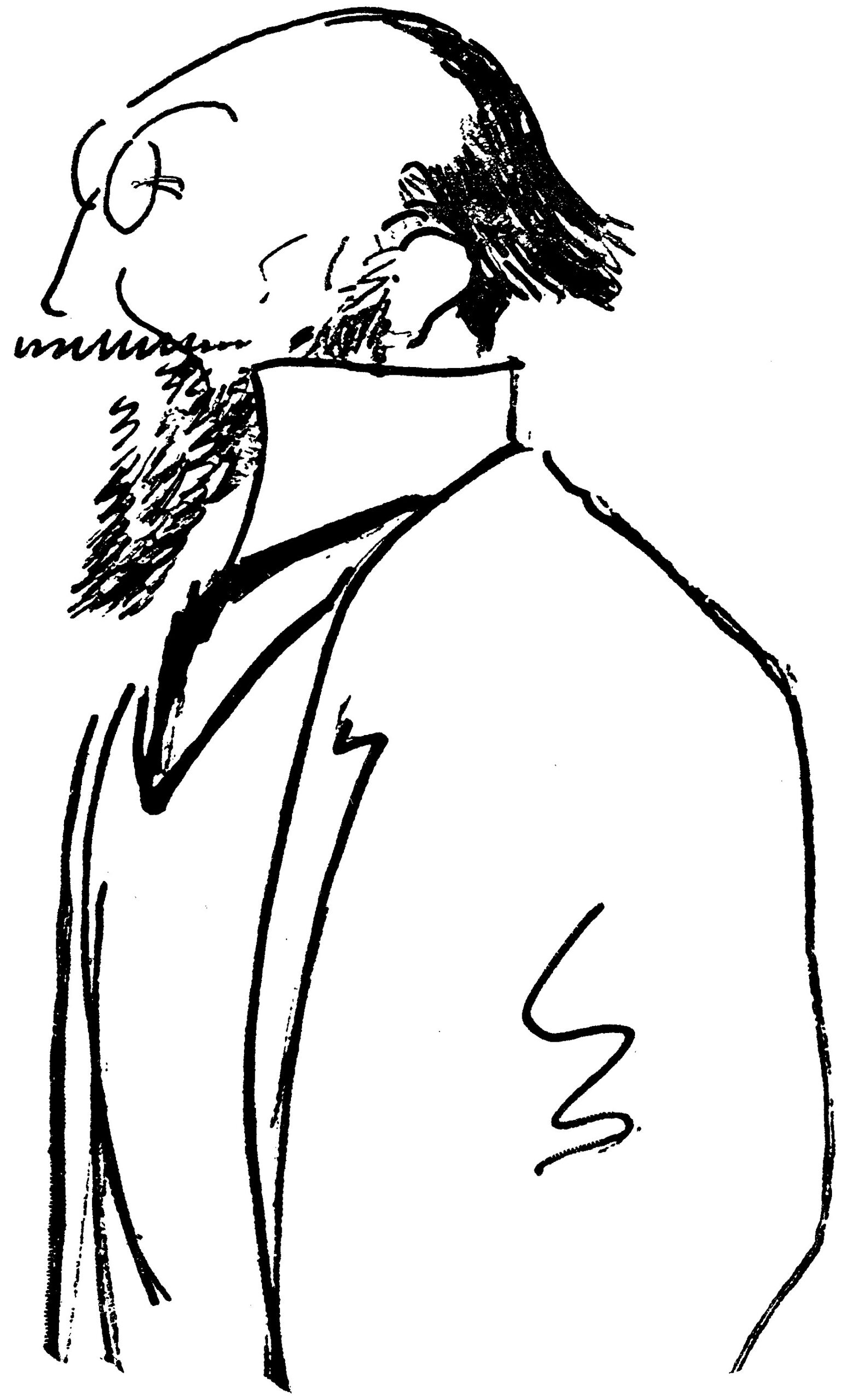

Alfred Frueh, caricature by Erik Satie, ca. 1917

Source: Wikimedia

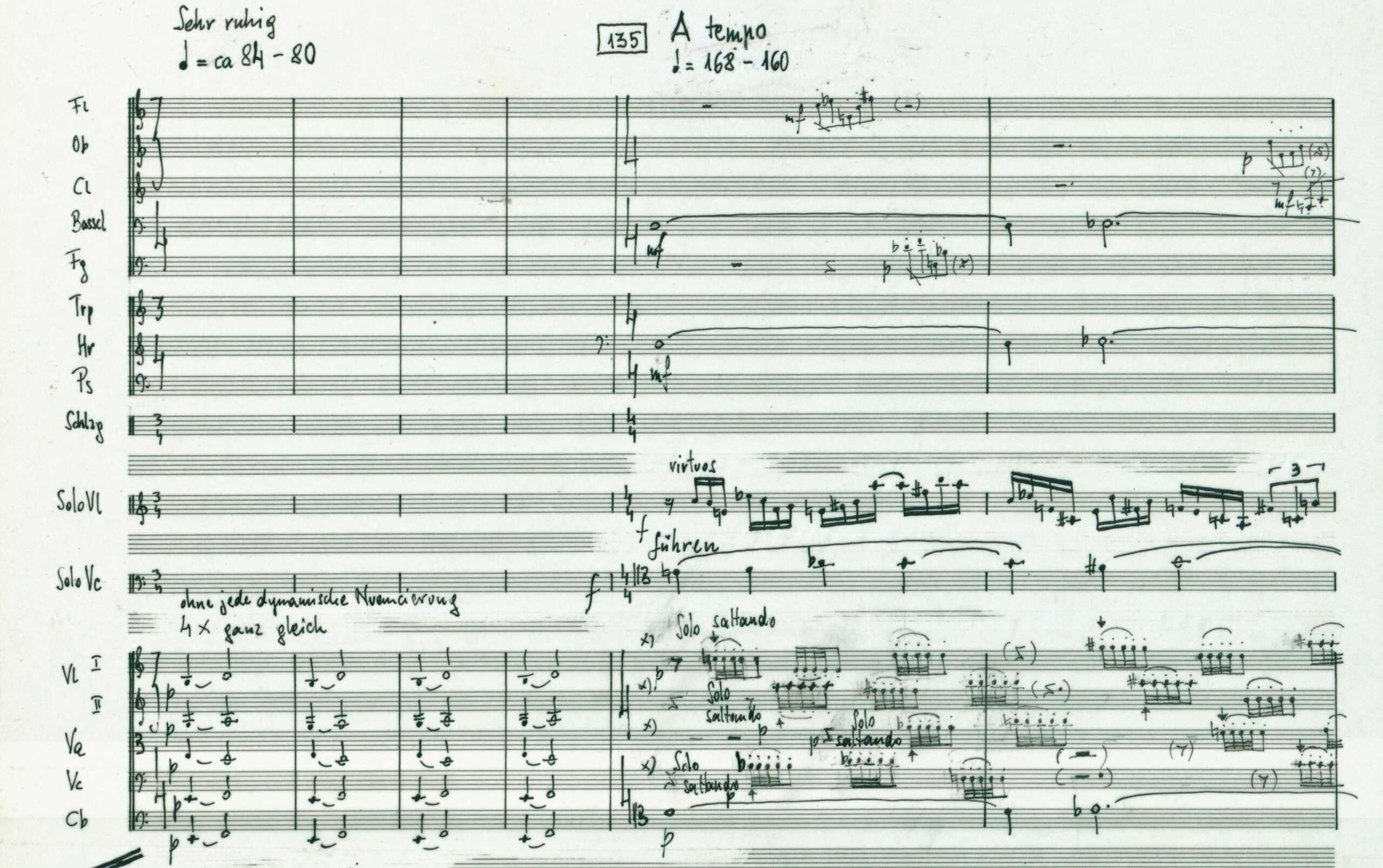

In Konzert für Violine, Violoncello und Orchester, Cerha set two worlds of sound on a collision course: Satie’s and his own. Or, more precisely, an “idiom developed, which could—within limits—be traced back to the Viennese school”.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 241 In three movements, he explores the question of if and how the two types of music can be reconciled with one another, where they push each other away, and where it even becomes possible for them to merge. Dramaturgically, the piece is held together by the interplay of the orchestra and the two solo parts, performed at the premiere by Cerha’s friends Ernst Kovacic (violin) and Heinrich Schiff (violoncello). All three movements explore different types of connection. In the first, “the basic elements lay side by side, seemingly unrelated.”Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 242 The concert starts out with stirring beats, “energetically gripping”, over which the two soloists unfold their interwoven melody lines—highly expressive music. The dramatic tracks run like a river across uneven land, sometimes seeping away, sometimes tumbling wildly. For a long while, we hear nothing of Satie, until he suddenly (almost like a ghost) appears in the aftermath of an orchestral outburst. Mild, dreamy, undulating chords create a counterpoint to the powerful symphonic figures. “Satie’s music is inserted with knife-like precision.” There are further episodic interventions throughout the course of the movement, with feverish highlights that again and again result in a brief citation of Satie. The viewpoint on Satie: lightweight, light-hearted, and effortlessly comprehensible.

Cerha, Konzert für Violine, Violoncello und Orchester, 1st Movement, mm. 131 ff

Cerha, Konzert für Violine, Violoncello und Orchester, 1. Satz, Satie-Einschübe

Ensemble „die reihe“, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha, Ernst Kovacic (Violine), Heinrich Schiff (Violoncello)

Bak, Friedrich and Gertraud Cerha’s private collection, Vienna

Foto: Christoph Fuchs

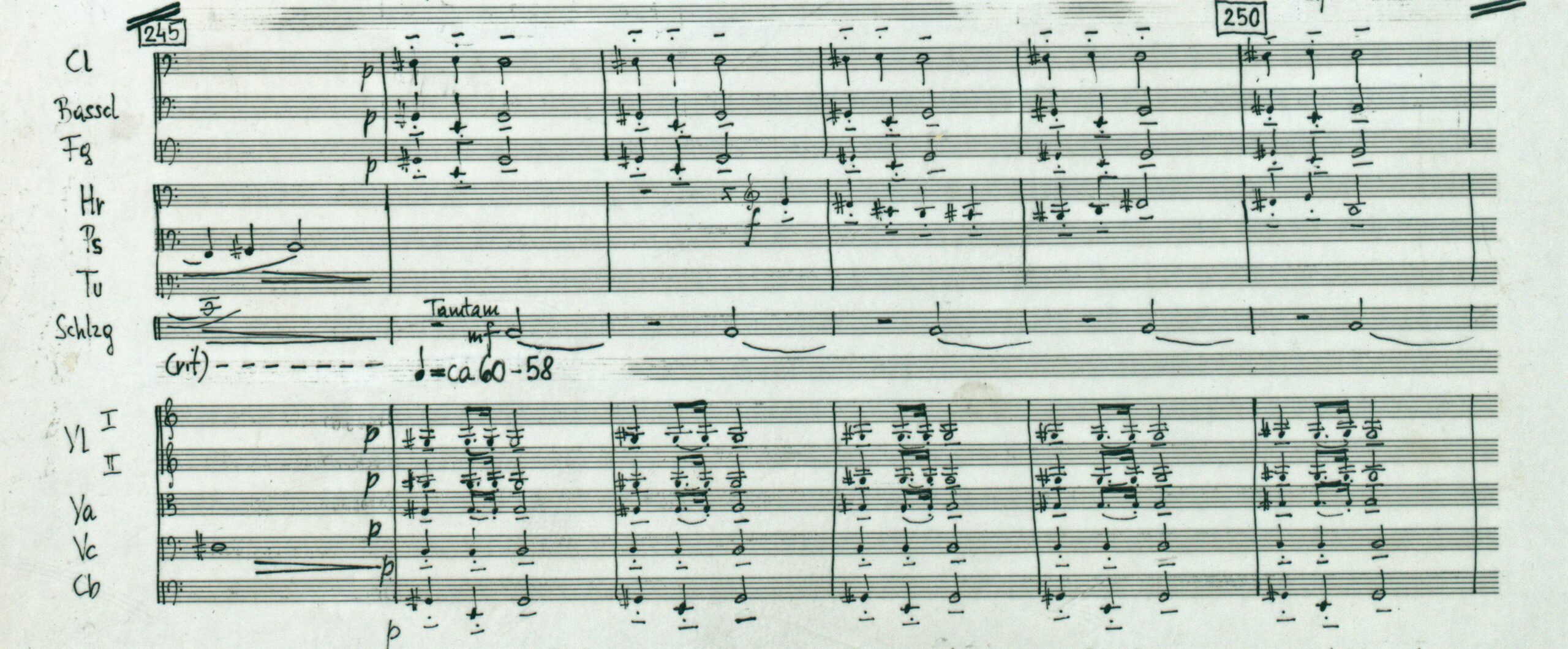

This new world of sound is bizarre: the bass crumhorn glissades like a siren, blackened by the sound of the bass clarinet and punctuated by the beating of a gong. The sounds of the bak, on the other hand, are completely isolated in space. Fractures and cracks continue to characterise the further development, which unrolls as if in a film. The opening orchestral masses reappear, as does Satie’s music. However, the listener now encounters a different Satie: Several short fragments of a funeral march flash out from the Entr’acte. The grief, however, has ironic undertones. Satie was parodying the Marche funèbre by Frédéric Chopin, extremely popular in his time and still considered a cliché of funeral music today. Cited yet again by Cerha, it now stands not on a double but on a triple false bottom, emerging as a kind of grotesque memory.

Cerha, Konzert für Violine, Violoncello und Orchester, 2nd Movement, mm. 245 ff. (citation of the funeral march)

Cerha, Konzert für Violine, Violoncello und Orchester, Beginn des 2. Satzes

Ensemble „die reihe“, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha, Ernst Kovacic (Violine), Heinrich Schiff (Violoncello)

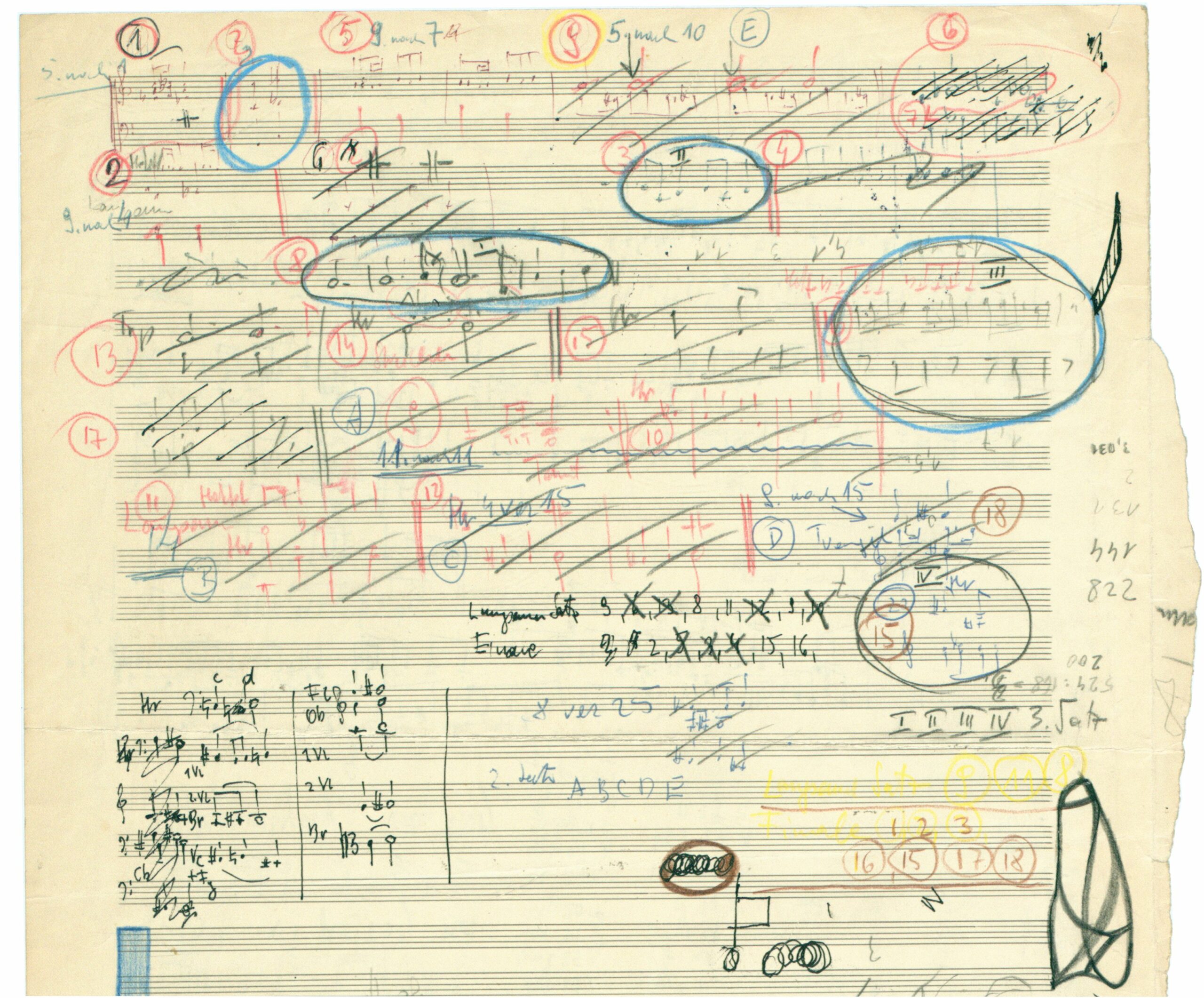

The third movement goes in a completely different direction than the first two, which introduce Satie only sparingly—a furious finale. From the very first note, it presents itself as an agile dance, primarily thanks to the pounding rhythm of the congas. Next come sporadic short figures from the orchestra—we are moving forward. For the instrumentalists, however, the dance around the congas is just a warm-up, setting the direction for what is to come: technical skill, brilliance, and pleasure. In keeping with the concert tradition, the two soloists come to the foreground after the drummed introduction. They play in duet, first lyrically, then with greater dexterity. Their harmonious unity, however, doesn’t last long, giving way to a sound spiral of excitement. “Wildly storming in”, the solo cellist initiates the change by first picking up the conga rhythm and then developing it further. This also alters the surrounding orchestral music. Fragments from Satie’s world become clearly audible in the accompaniment, stylistically assuming the steering wheel. Most of the citations originate from the film music for Entr’acte, an often circus-like aura of sound which now completely takes over Cerha’s concert. Other references cannot be clearly identified and were probably compiled from bequeathed fragments of Satie’s work.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 242 One of the sketch pages for the concert shows how Cerha collected these small building blocks from Satie’s music: He would jot down a skeletal outline of their essence, with notes on instrumentations and arrangements alongside.

A closer examination of the sketches reveals the montage technique Cerha used to compose the music in the traditional sense (from the Latin word componere, meaning to join together). It is their very nature that lends them the ability to be linked together so well: Satie’s Entr’acte is composed from tiny building blocks, usually consisting of a bar that is then multiplied to create a pattern. Change only occurs when these patterns are replaced by others. Cerha proceeds in the same way. It is hardly noticeable that the sound patterns he strings together didn’t originally belong together in this order—after all, even in Satie’s work they don’t follow a strict development, but instead combine situationally, on the whim of the moment to a certain extent. The individual parts look like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle and have a wide range of possible combinations. By dismantling and reassembling Satie’s musical puzzle, Cerha creates an overall picture that is similar yet not congruent with the original. By abstracting from the musical character, a viewer could recognise a kind of merry-go-round. In Cerha’s transformation, this carousel spins faster and faster: Satie’s phrases powerfully “heat up” the “goings on of the concert”.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 242

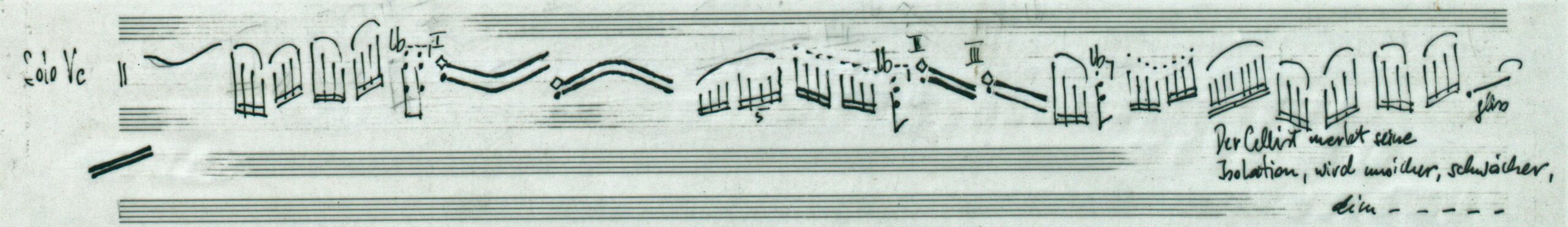

The ecstasy of this river of sound quickly reveals that it’s not only music unfolding, but also theatre. While the concert audience’s attention is focused on the frenzied solo cello’s breakneck runs and unhinged glissandi with no rest, the solo violin is pushed off to the side. Despite its silence, it still manages to take part in the happenings—yet purely in pantomime. Precise theatrical instructions are noted in the score, something seen nowhere else in Cerha’s oeuvre. “Increasingly annoyed and listless,” he writes, the solo violin should “look down at the cellist, who is playing like crazy with growing passion” and finally turn away with the “violin under his arm”.Cerha, Konzert für Violine, Violoncello und Orchester, handwritten score, AdZ, 00000081/68 ff Just as this breakthrough from the purely acoustic sphere into the performing arts takes place, the music also changes, drawing closer and closer to parody. Supporting this, the orchestral accompaniment and the solo part move in opposite directions: The quoted Satie particles gradually erode, until nothing remains of them; only the drummer stays, rubbing glass paper “always the same way, like a machine”. The solo cello, on the other hand, abandons all seriousness and culminates in a parodying cadence that eliminates fixed pitches entirely. The result is a purely gestural music that follows the theatrical moment.

Cerha, Konzert für Violine, Violoncello und Orchester, 3rd Movement, mm. 503 ff. (solo cello)

Cerha, Konzert für Violine, Violoncello und Orchester, 3. Satz, Cellosolo

Ensemble „die reihe“, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha, Ernst Kovacic (Violine), Heinrich Schiff (Violoncello)

Satie and Cerha merge at this point, on a level that is more than just musical. It was not uncommon for Satie to turn the concert hall into a theatre space, and his original playing instructions often involved facial expressions and behaviours. Here and there, performers are told not to change their facial expressionsErik Satie, Les trois Valses distinguées (1914), or to “behave”, as a monkey might be watching.Erik Satie, Le piège de Méduse (1913) There is a keen sense of the comical and grotesque in these instructions, something which also informs the popular view of Satie—that of a “monastic clown”, as Cerha’s colleague Kurt Schwertsik poetically notes in the preface to his own homage to the Frenchman (the extended string quartet Adieu Satie). By tipping the music “into the absurd”,Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 242 Cerha’s concert piece becomes a circus act with high-flying acrobatic performances. However, the piece doesn’t end with this “gag”. Instead, it finds its way back to the centre, balancing itself out, so to speak. Satie’s world of sound does not disappear, but instead becomes fully integrated—a way of thinking typical of Cerha, if one recalls his involvement with cybernetic processes . Instead of emphasizing the strange, the rapprochement towards the end of the piece “ultimately leads even to fusion” See, for more in-depth information: Marco Hoffmann, “‘…der du das weihevolle Geraune durch Zirkus störtest’. Kurt Schwertsik, Friedrich Cerha und die Rezeption Erik Saties in Österreich”, in: Christian Heindl: Kurt Schwertsik und der Begriff der Moderne im Wandel [to be published 2021] of all the elements. Only the exotic bak clatters on, reminding the listener of an exciting cabinet of curiosities from a wide variety of sound sources.

Schatztruhe

Satie, Entr’acte cinéma, conductor’s score of Cerha