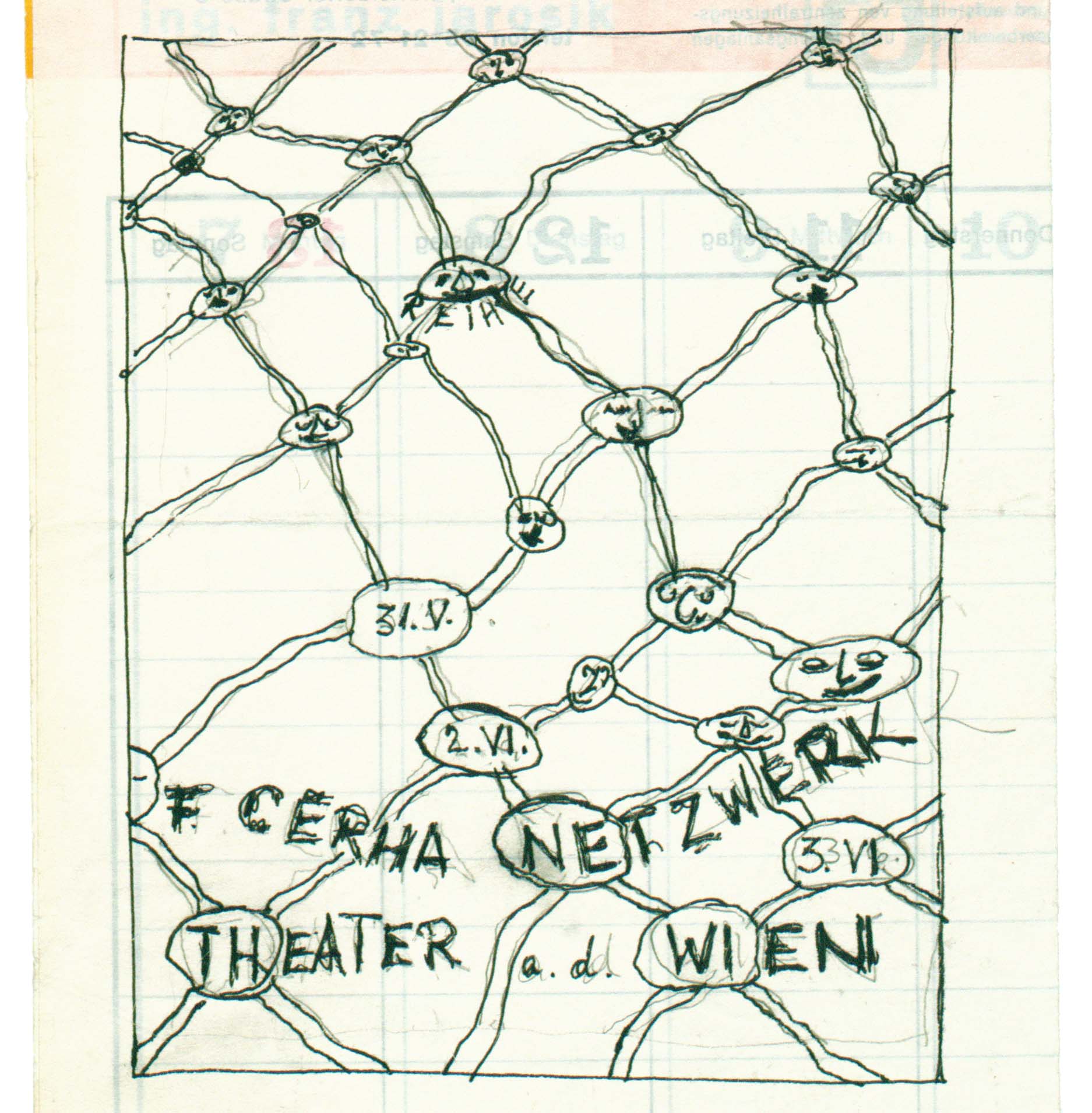

Netzwerk

Entanglements

Intersecazioni

Fasce

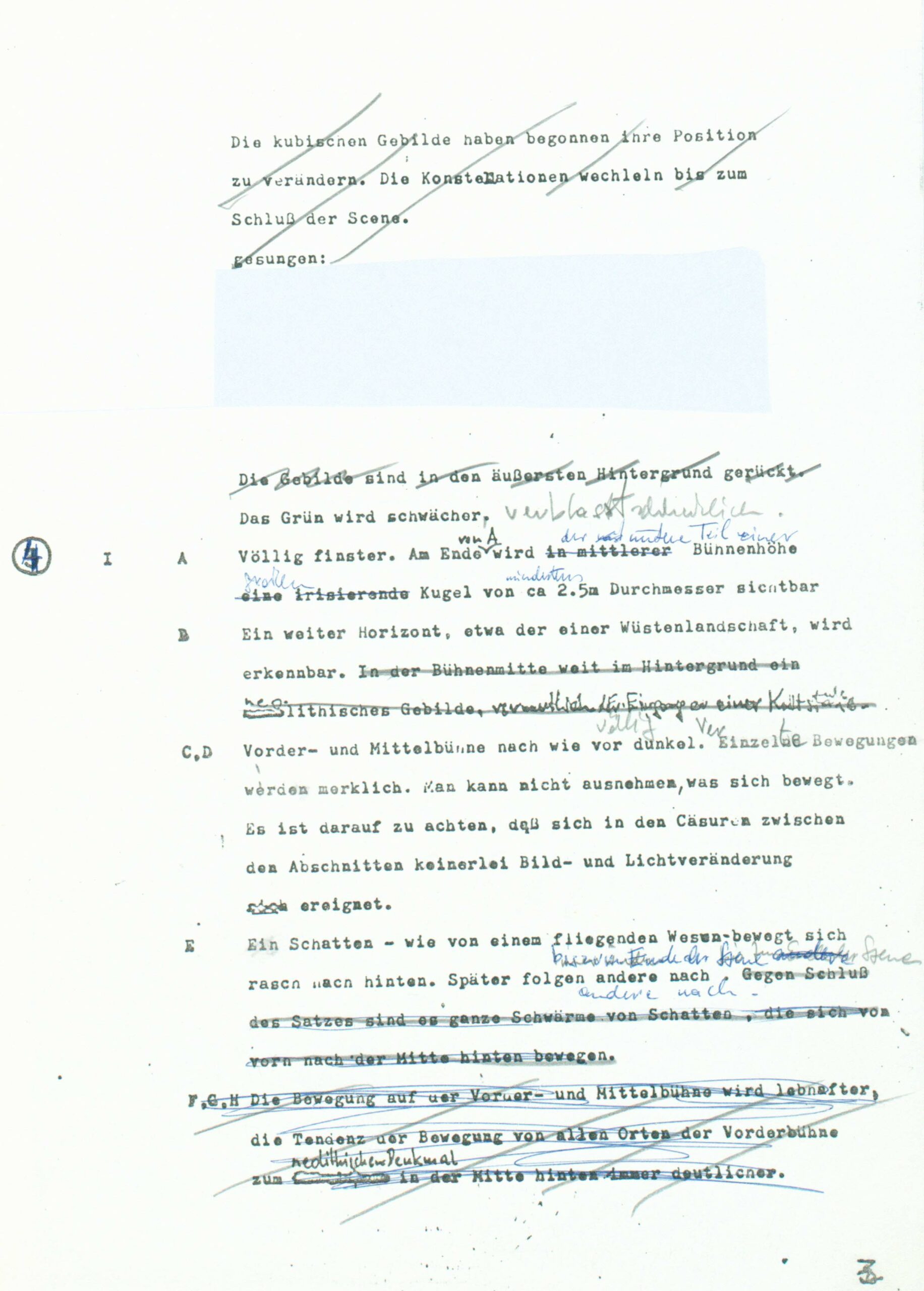

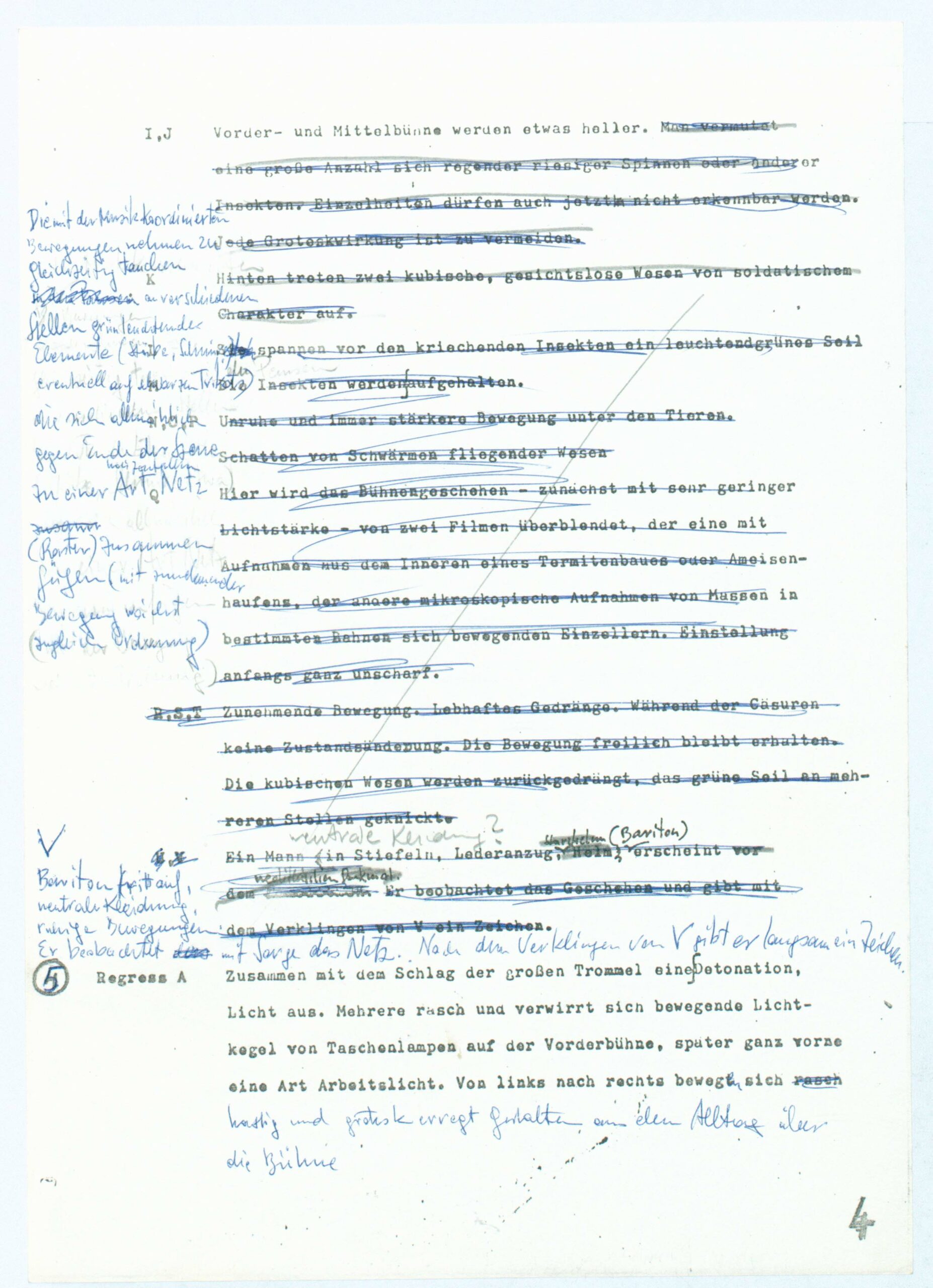

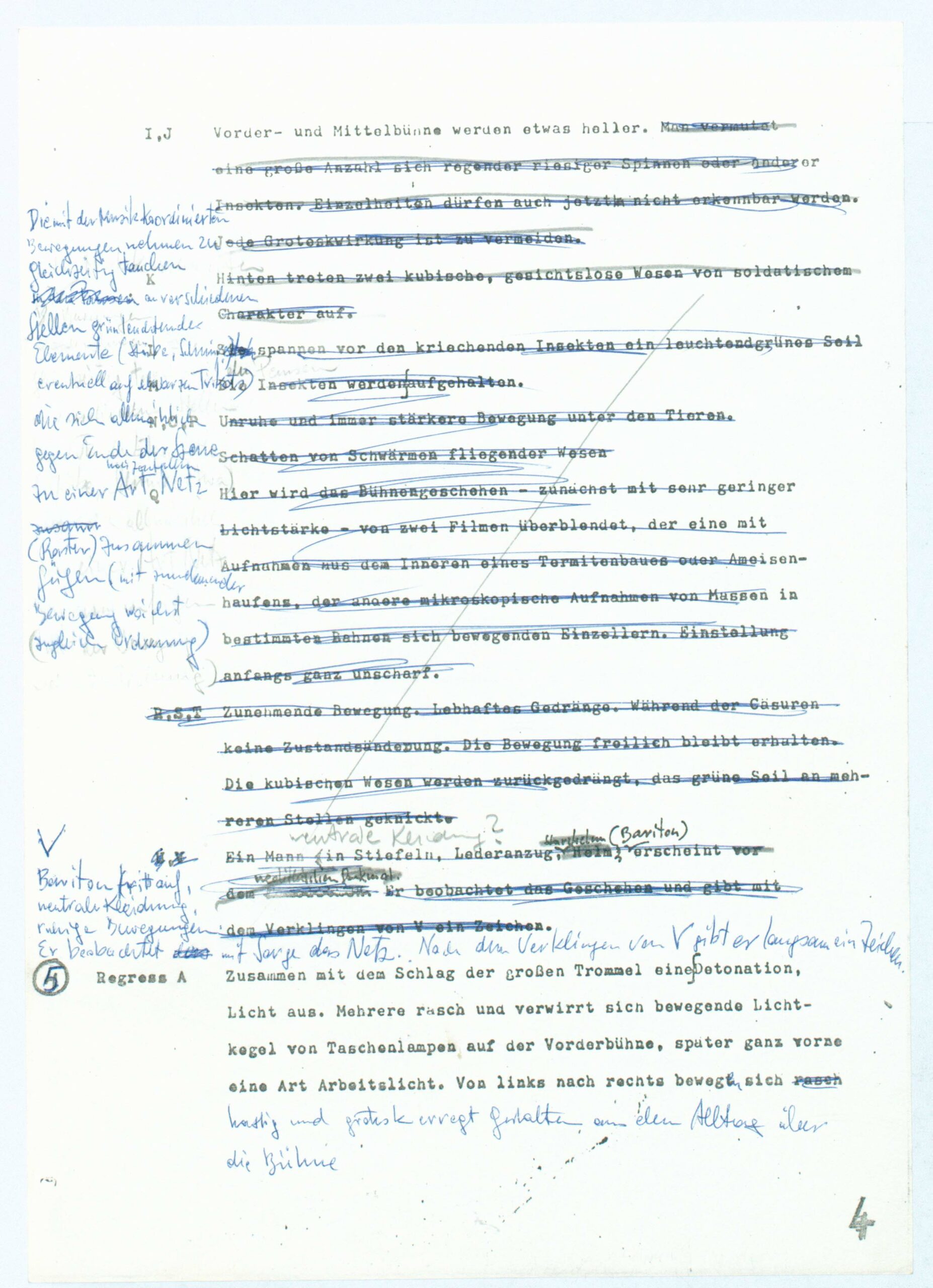

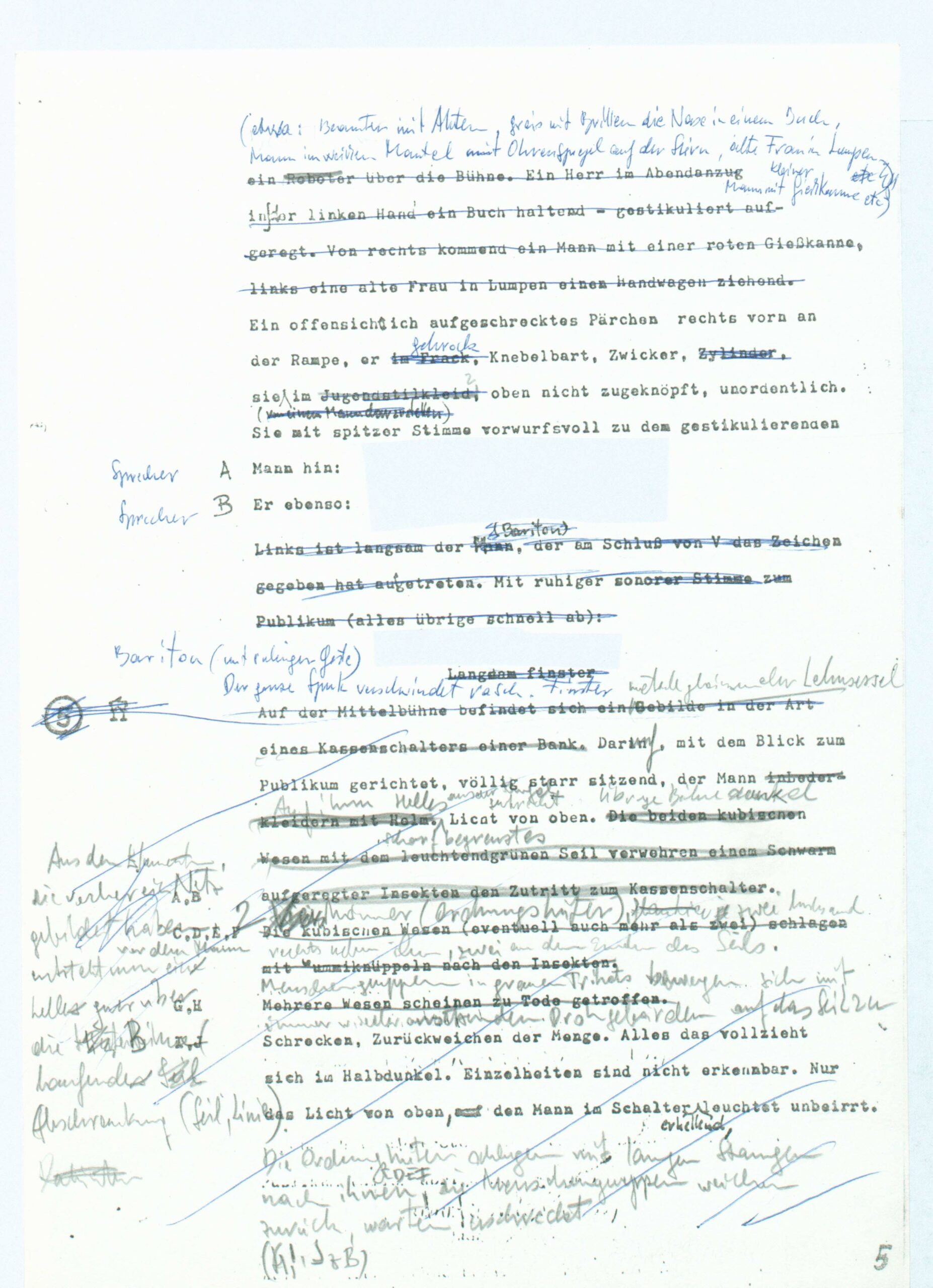

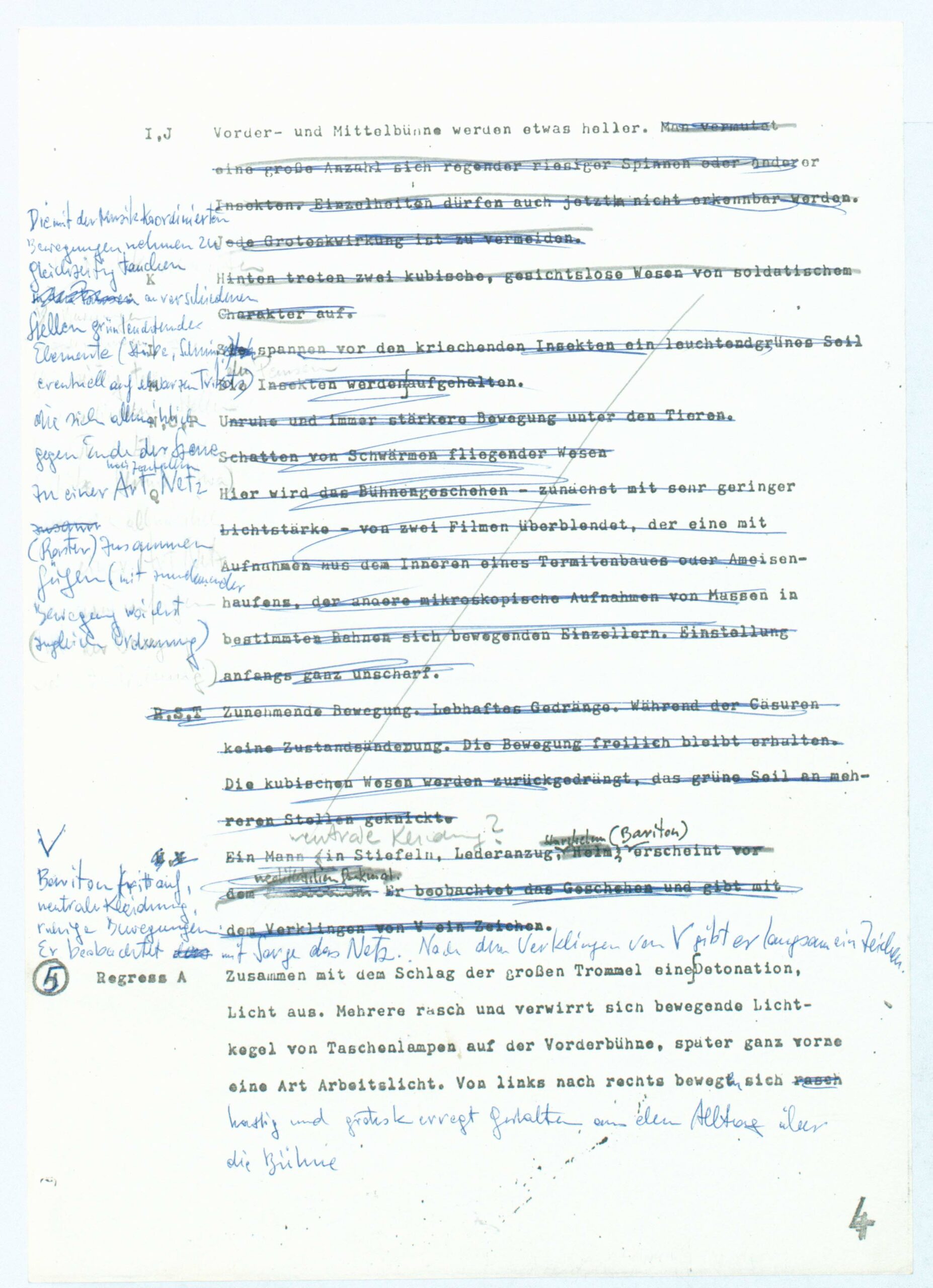

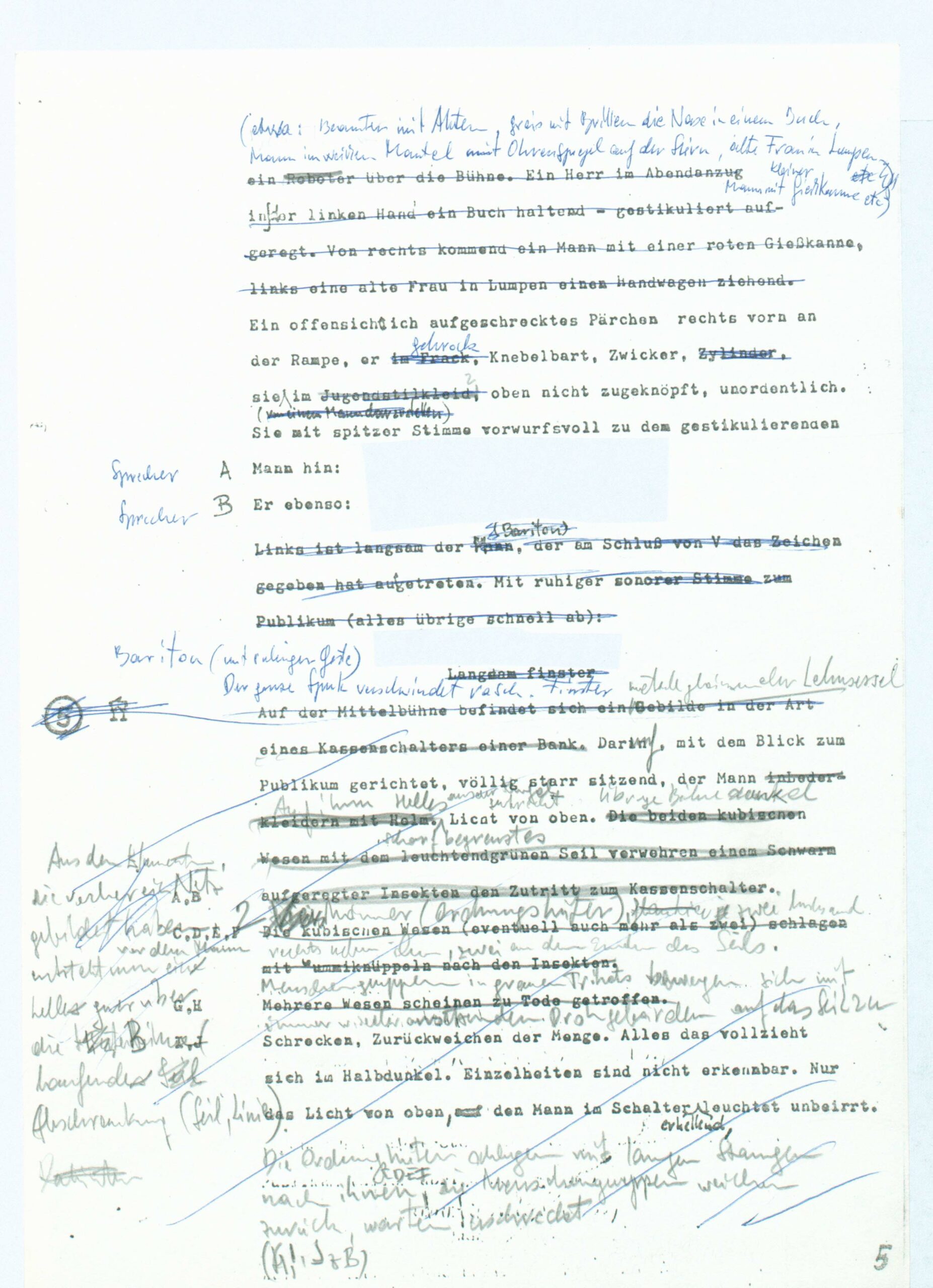

Friedrich Cerha, Netzwerk, Theater an der Wien 1981

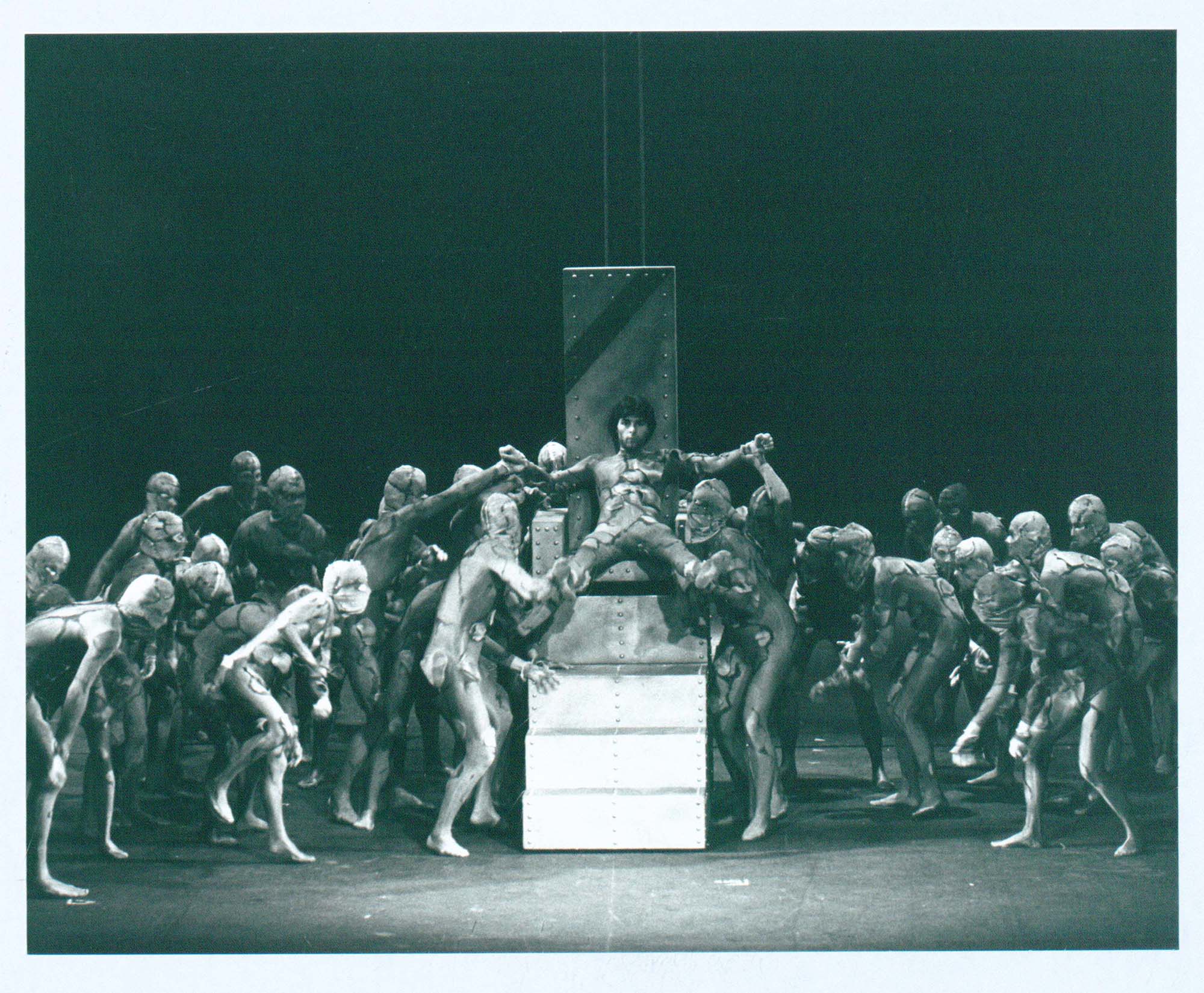

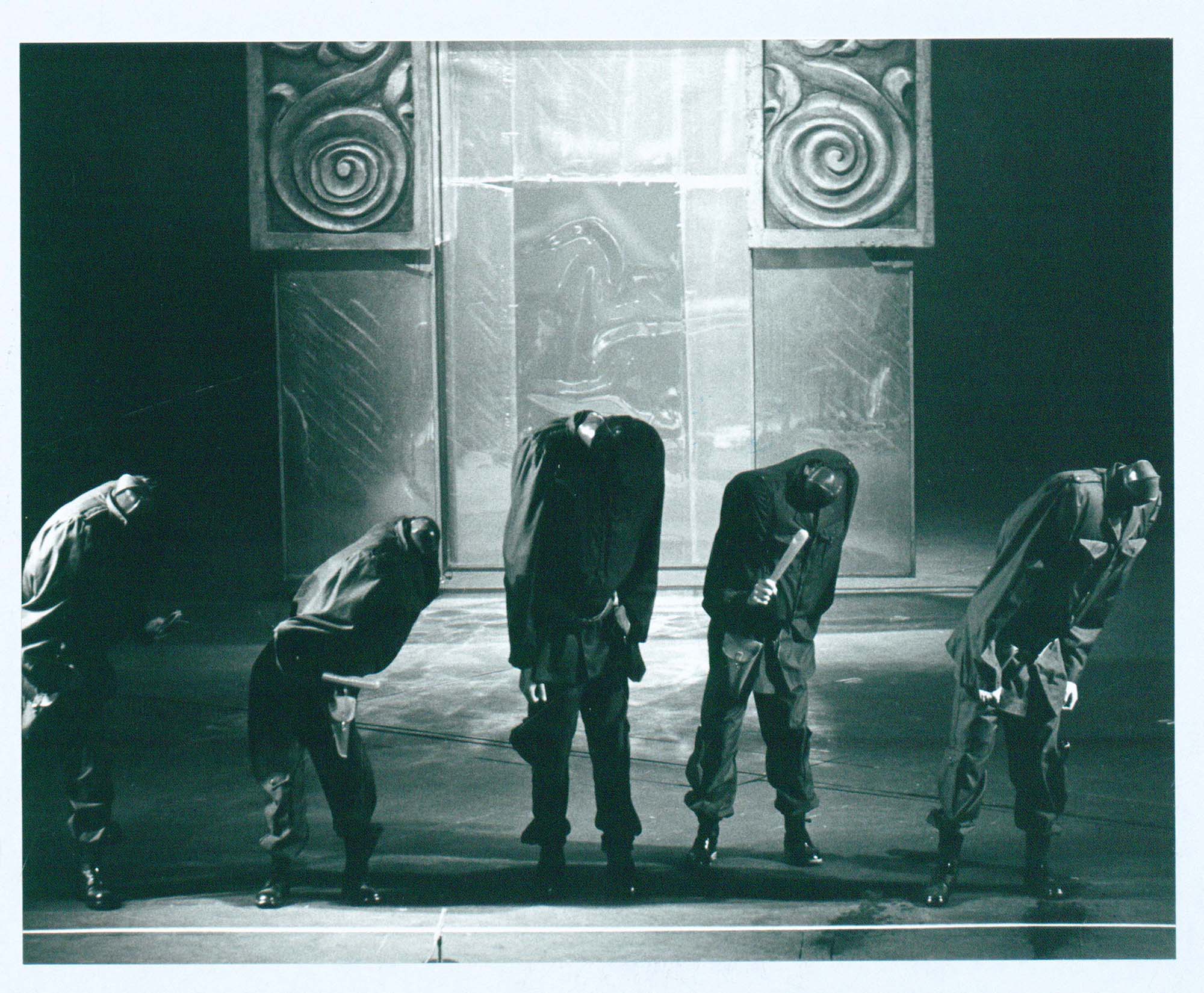

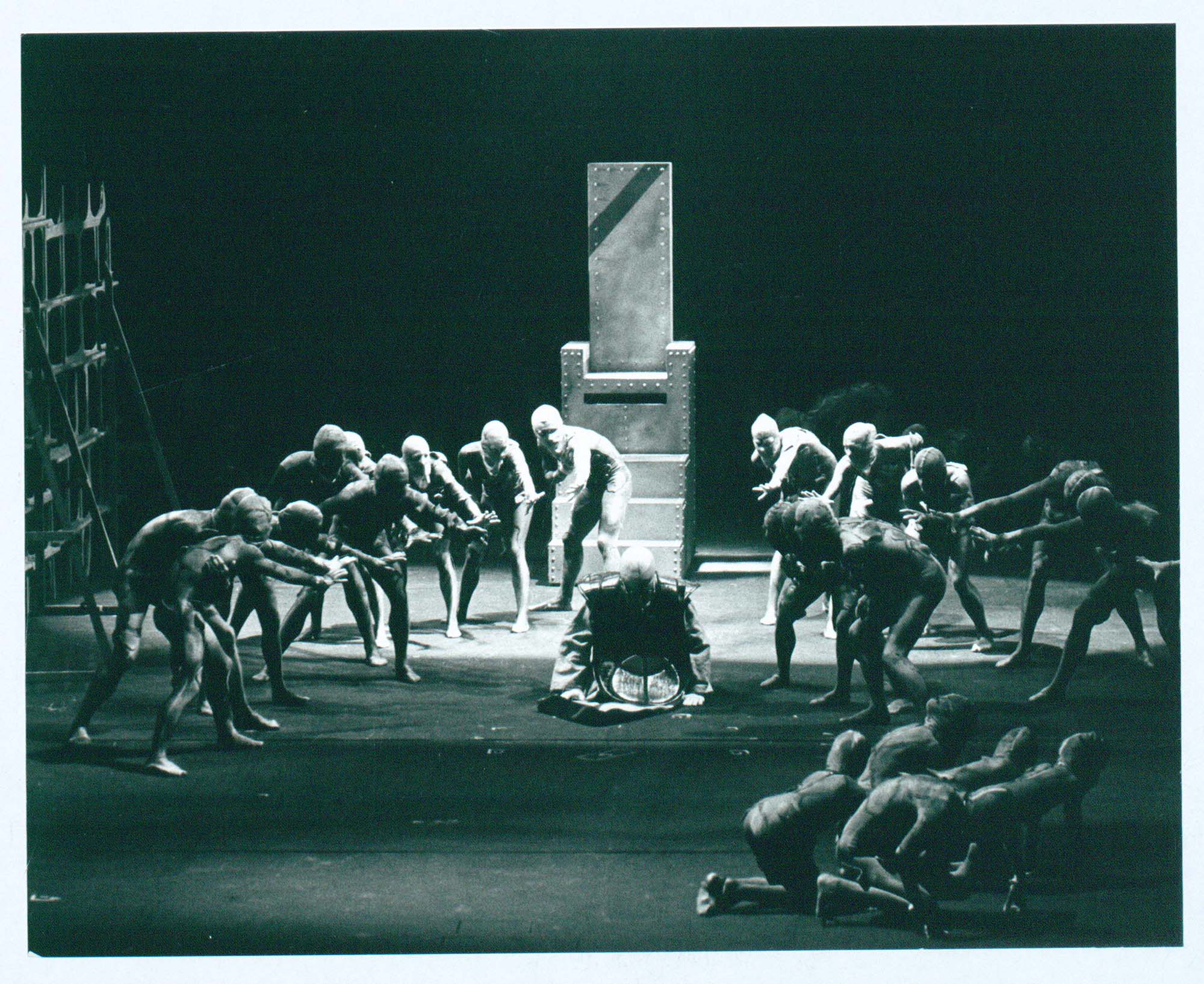

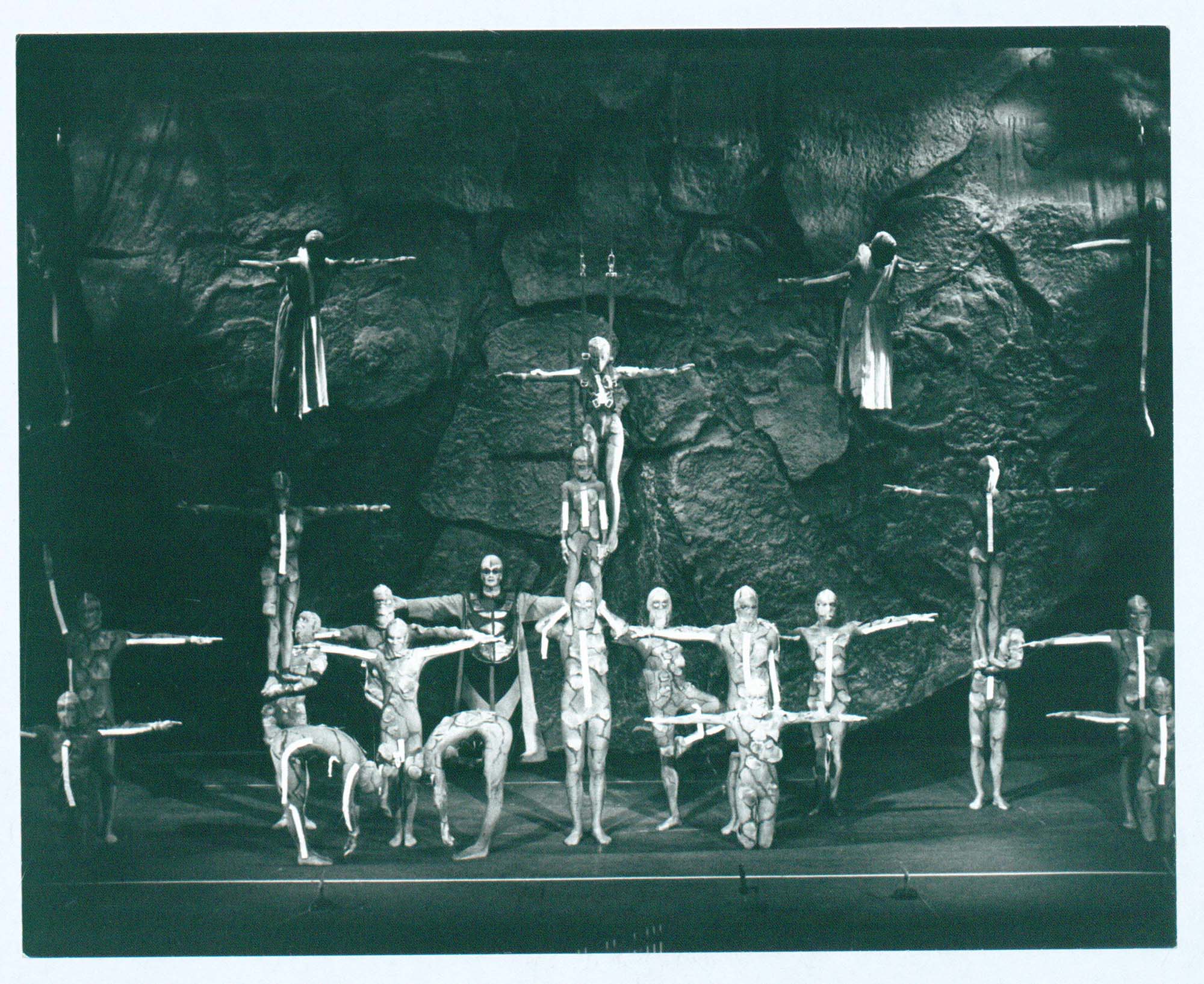

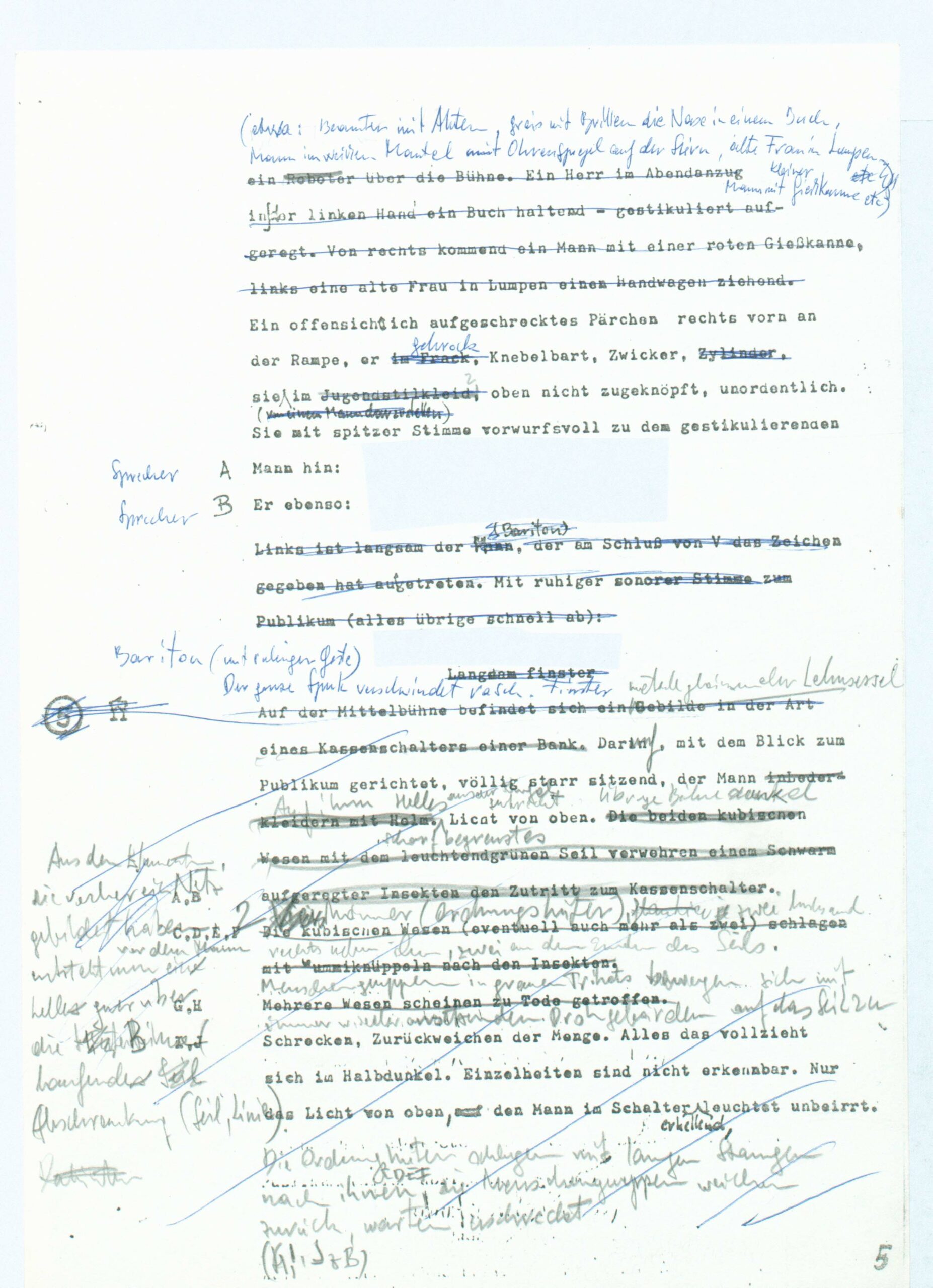

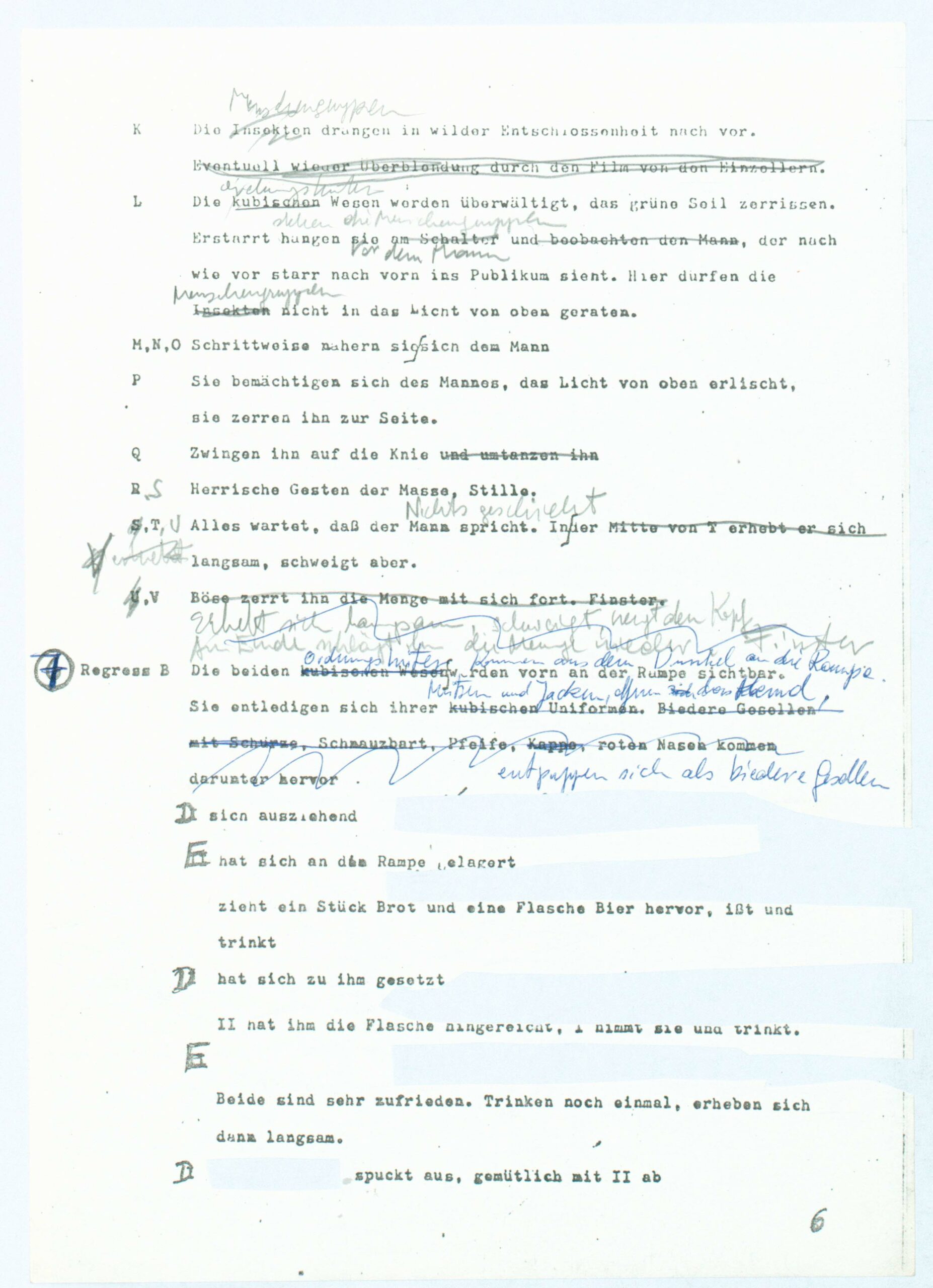

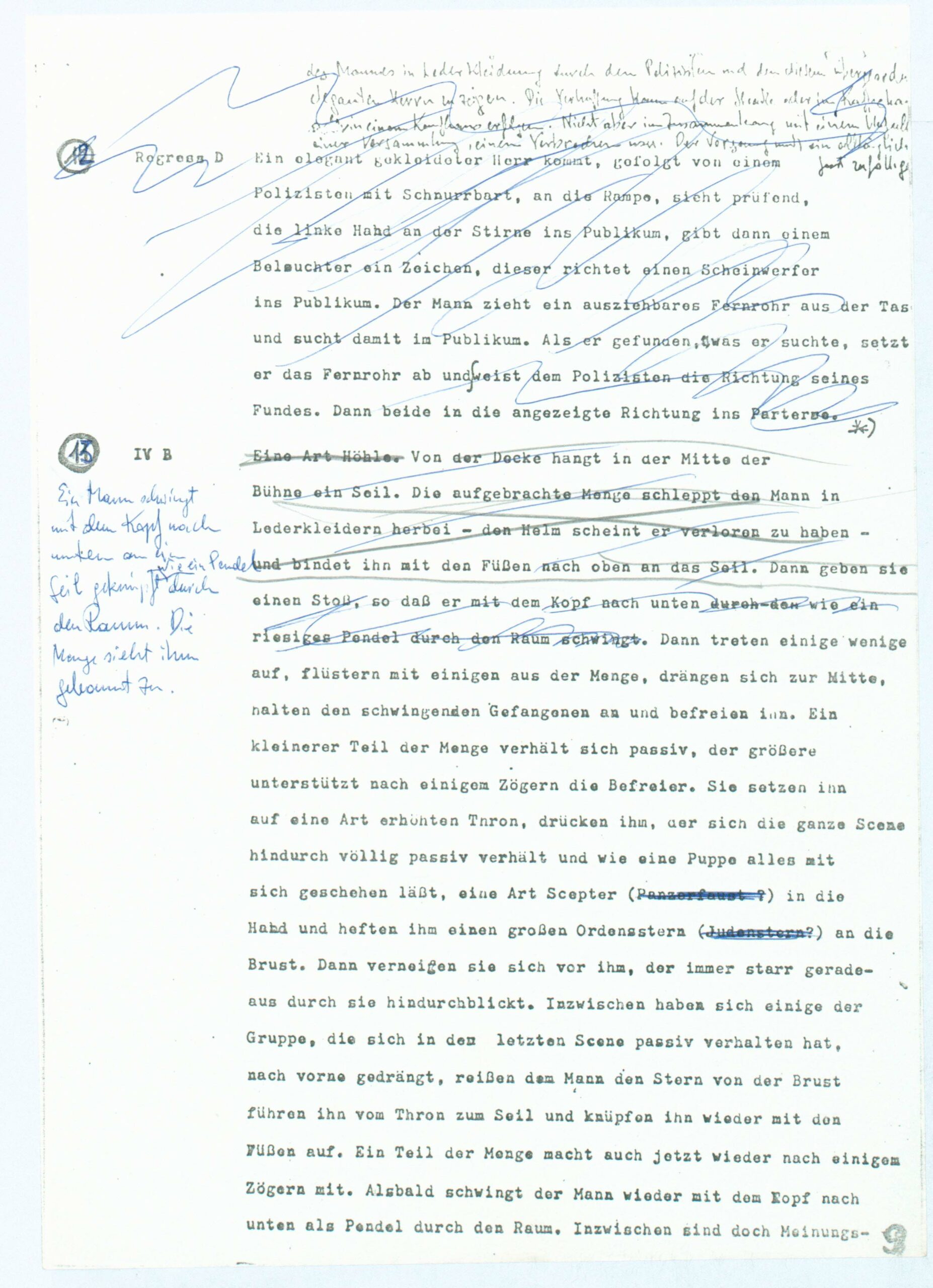

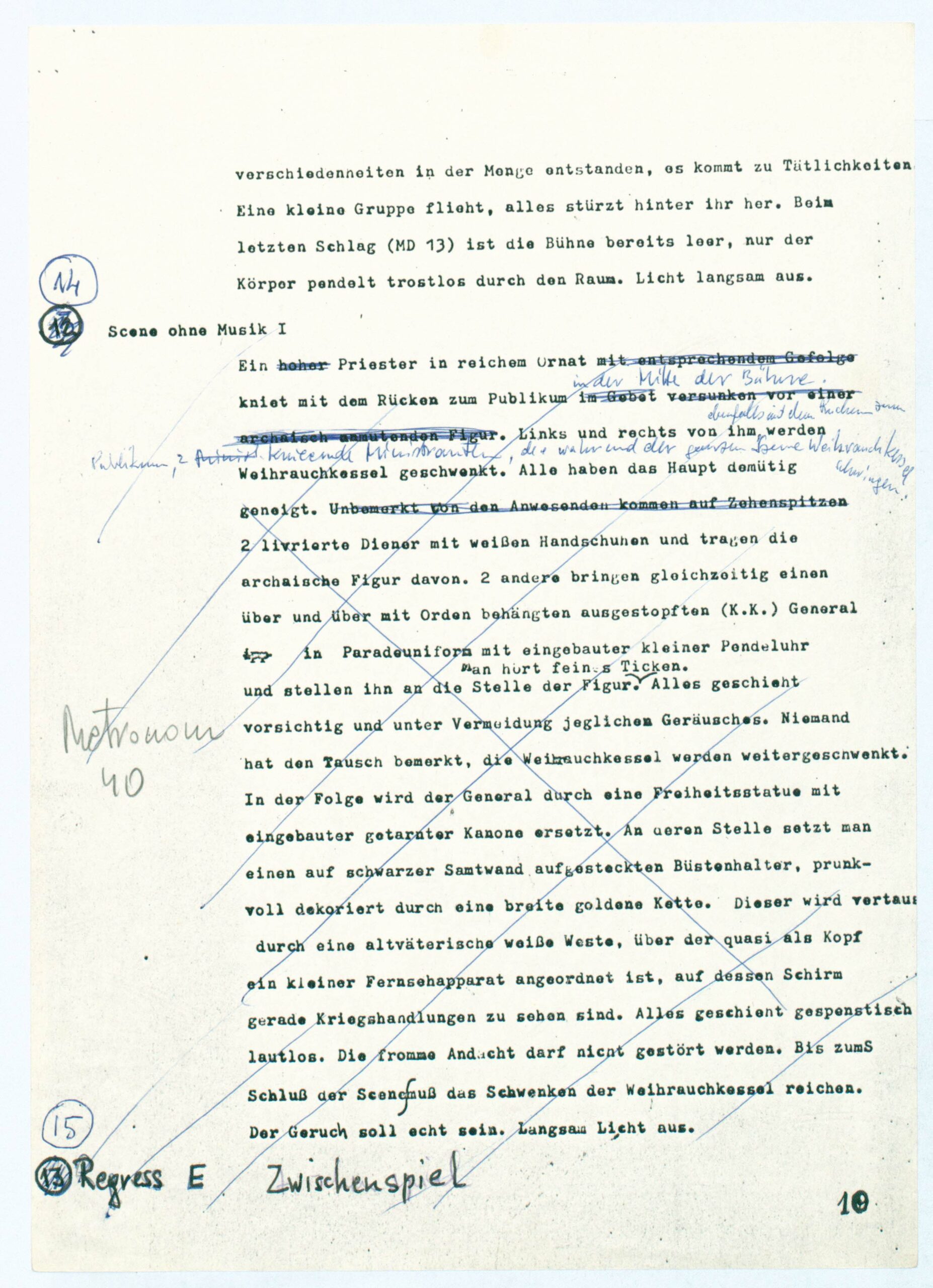

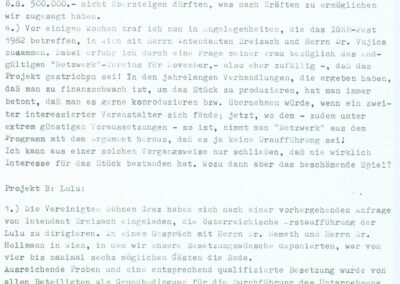

The set design for “Hauptsatz VIII B” and “Regress L” is probably the most prominent in Cerha’s work of musical theatre, Netzwerk. It features five men who, after initial attempts to reach the centre of a web, get stuck in it—a symbol of humanity’s dangerous entanglements with the world.

Photo: Archiv der Zeitgenossen

Ballet, theatre, opera, pantomime … These are some of the many labels that could be attached to Cerha’s Netzwerk—but none would likely stick for too long. Curtains up!

Produktion Wiener Festwochen 1981, Theater an der Wien,

Inszenierung: Giorgio Pressburger,

Choreografie: Ivan Marko,

Ensemble „die reihe“, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha, Peter Binder (Bariton)

The opening of the approximately two-hour play—Cerha’s first to be brought to the stage—uses theatrical gestures: A speaker tears down the curtain and begins a monologue that no one can understand. Still, the way he is speaking seems strangely intimate, as if he is announcing ideas that go beyond words. His speech is followed by images from primeval eras: Orbiting planets, blurred flickering shapes, darkness. A human voice rings out from nowhere, godlike. The symbols Cerha uses reveal what Netzwerk is really about: It is a draft for modern world theatre.

Außenansicht

Cerha finished the score for Exercisesin 1967, bringing years of work to an end. However, the composer initially had no idea what role the piece would play in the cultural scene. „What will people do with it?”Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 84” asked Cerha after finishing the composition, knowing full well that Exercises was created Exercises “without regard to the requirements of the apparatus”.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 84

Although the play premiered the next year and was soon followed by many other performances, the story of Exercises did not conclude for a long time. In 1967, a note by Cerha announced something that wouldn’t come to pass until the early 1980s: The adaptation of the piece for the theatre:

From the very beginning, visual ideas followed me while working on the individual movements of Exercises. I was already thinking of creating a play or a film based on the arrangement of the musical work. As in the piece, it would not be necessary to depict a logical plot unfolding, but rather to examine the possibilities for existence through an individual’s various attempts, which are triggered by related drives. The idea of combining a play and a musical work initially made me uncomfortable. However, while thinking about it and working, everything suddenly happened unavoidably, I would almost say, of its own accord.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 83

Scene photos of Netzwerk, Vienna 1981, AdZ, 000F0078

Brücke

The path from Cerha’s first musical notes in 1961 to the stage performance 20 years later raises a crucial question: Can Netzwerk even be considered a piece in its own right? Or is it nothing more than Cerha’s Exercises, hiding in the guise of a play? There is no clear answer. While it is true that Exercises is the backbone of Netzwerk, resulting in a great deal of crossover between the two pieces, there is nevertheless a clear distinction. When Cerha finally had the chance to stage his play in 1978, he reopened the “organism” of Exercises, looking to unearth and add new limbs. “Several transformations and extensions“Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 235 contributed to a metamorphosis that ultimately resulted in a far richer piece. The telling title Netzwerk refers to this newly created wealth of relationships: As in an actual network, far-arching connecting lines play an important role—yet not everything is connected to everything else, instead joining together at specific, prominent hubs. This results in spaces for open development, conscious connections, links, and interfaces.

The title Netzwerk also draws attention to a special facet: the affiliation of the piece to the body of Cerha’s work inspired by cybernetics. The names of two cyberneticists are indispensable when looking at this interesting area: Norbert Wiener and William Ross Ashby. Both were scientists—Wiener primarily a mathematician, Ashby mainly a psychiatrist—and among the founders of the interdisciplinary school of thought that was systematically explored starting in around 1946. Cerha explored the work of both scientists thoroughly during the burgeoning composition of Exercises.

His reading of Wiener’s writings in the mid-1960s had a noticeable impact on the genesis of Exercises. In connection with his previous collaborations with engineer and sound technician Hellmut Gottwald, who helped composers realise their ideas at the Vienna Studio für Elektronische Musik, Cerha came across Wiener’s book Cybernetics and began to study it:

A particular interest in “machines that learn and reproduce”, a chapter Wiener added in the second edition of his book in 1961, plays an important role in Exercises. To a certain extent, Cerha’s music also learns and reproduces, always informed by changes in skilfully staged conditions.

In 1966, Cerha even jotted down two quotations from Wiener’s autobiography on “a page of the score from this period“Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 80. The first of these citations describes the structure of Cerha’s heterogenous Netzwerk with remarkable aptness:

Organization we must consider as something in which there is an interdependence between the several organized parts but in which this interdependence has degrees. Certain internal interdependencies must be more important than others, which is the same thing as saying that the internal interdependence is not complete, and that the determination of certain quantities of the system leaves others with the chance to vary. This variation from case to case is a statistical one, and nothing less room than a statistical theory has enough room in it for the notion of organization to be significant.

Norbert Wiener

Zitiert in: Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 80

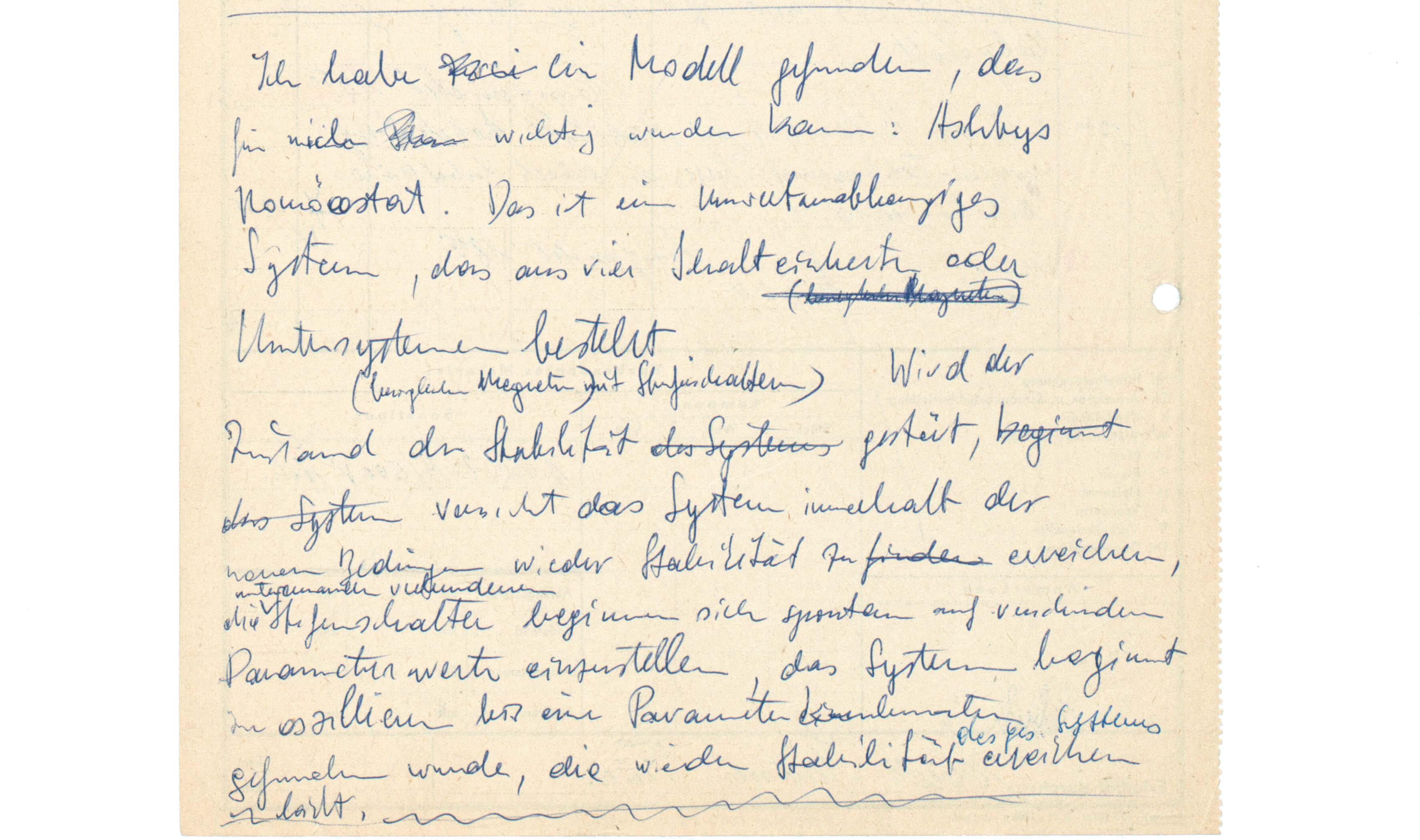

No less important than coming across Wiener’s writings was Cerha’s discovery of one of Ross Ashby’s mechanical devices. Ashby developed one of the earliest tools in the field of artificial intelligence, a circuit made up of four electromagnetic blocks. Ashby christened his machine the “Homeostat”, after the nineteenth-century biology concept of homeostasis, which describes how organisms maintain balance. This became a comprehensive poetic theme for Cerha, and in 1966 he wrote in his notes on Exercises:

I have found a model that may become important to me: Ashby’s homeostat. It is an environmentally autonomous system consisting of four switching units or subsystems (moving magnets with step switches). If the state of stability is disturbed, the system tries to regain it within the new conditions: the interconnected step switches begin to spontaneously adjust to different parameters, and the system begins to oscillate until it arrives at a parameter combination that allows the stability of the system to be restored.

Friedrich Cerha

Cerha, Notizen zu Exercises, AdZ, 000T0061A/43

Ashby’s manuscripts indicate that he began sketching the homeostat as early as the 1940s. When it was finally built in 1948, Ashby used it to create what was probably the first truly cybernetic apparatus. It looked cryptic and futuristic, conveying a nuanced poetry of balance, which Cerha then made his own.

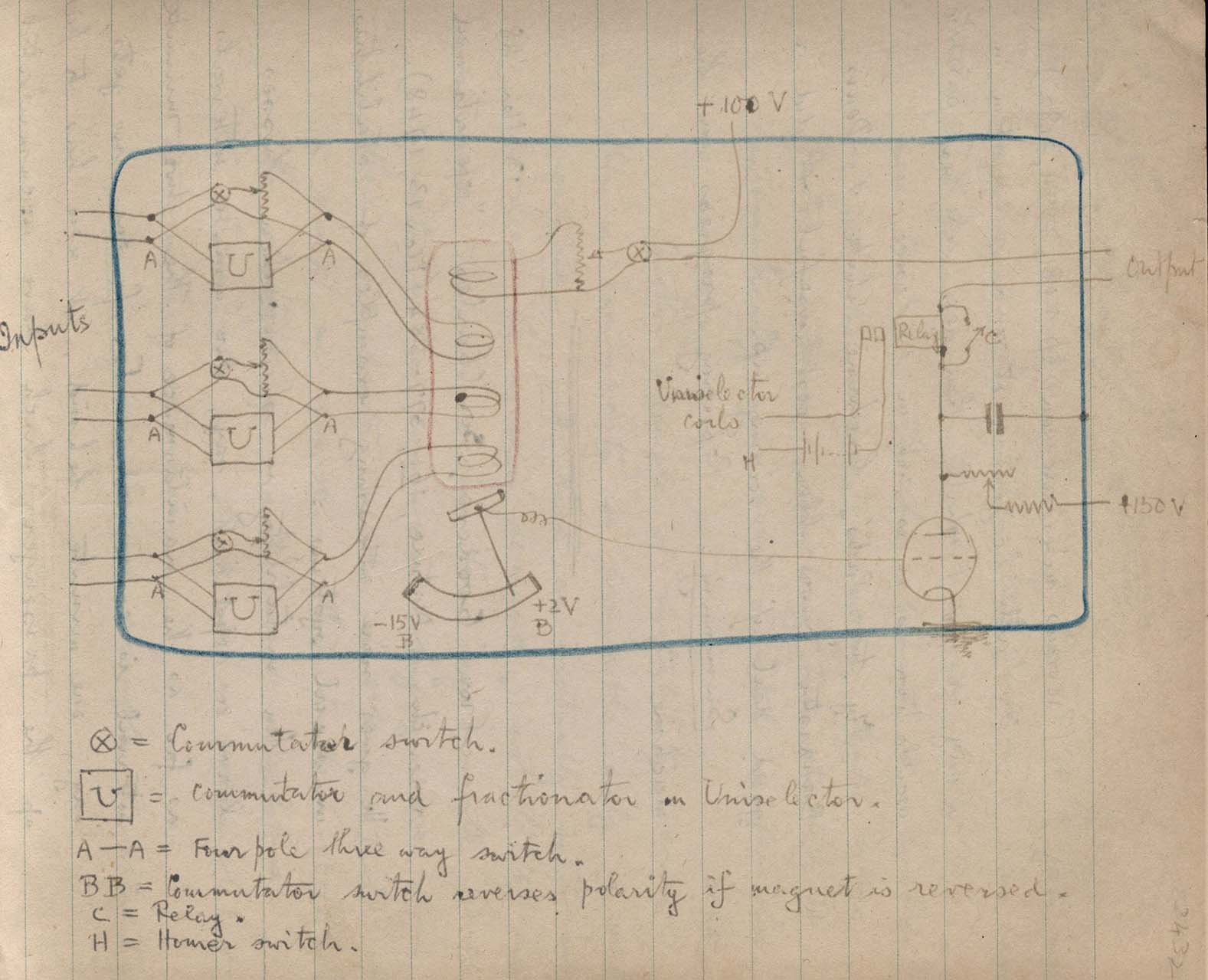

W. Ross Ashby, Eleventh Journal, Drawing of a Homeostat (Circuitry), 1948

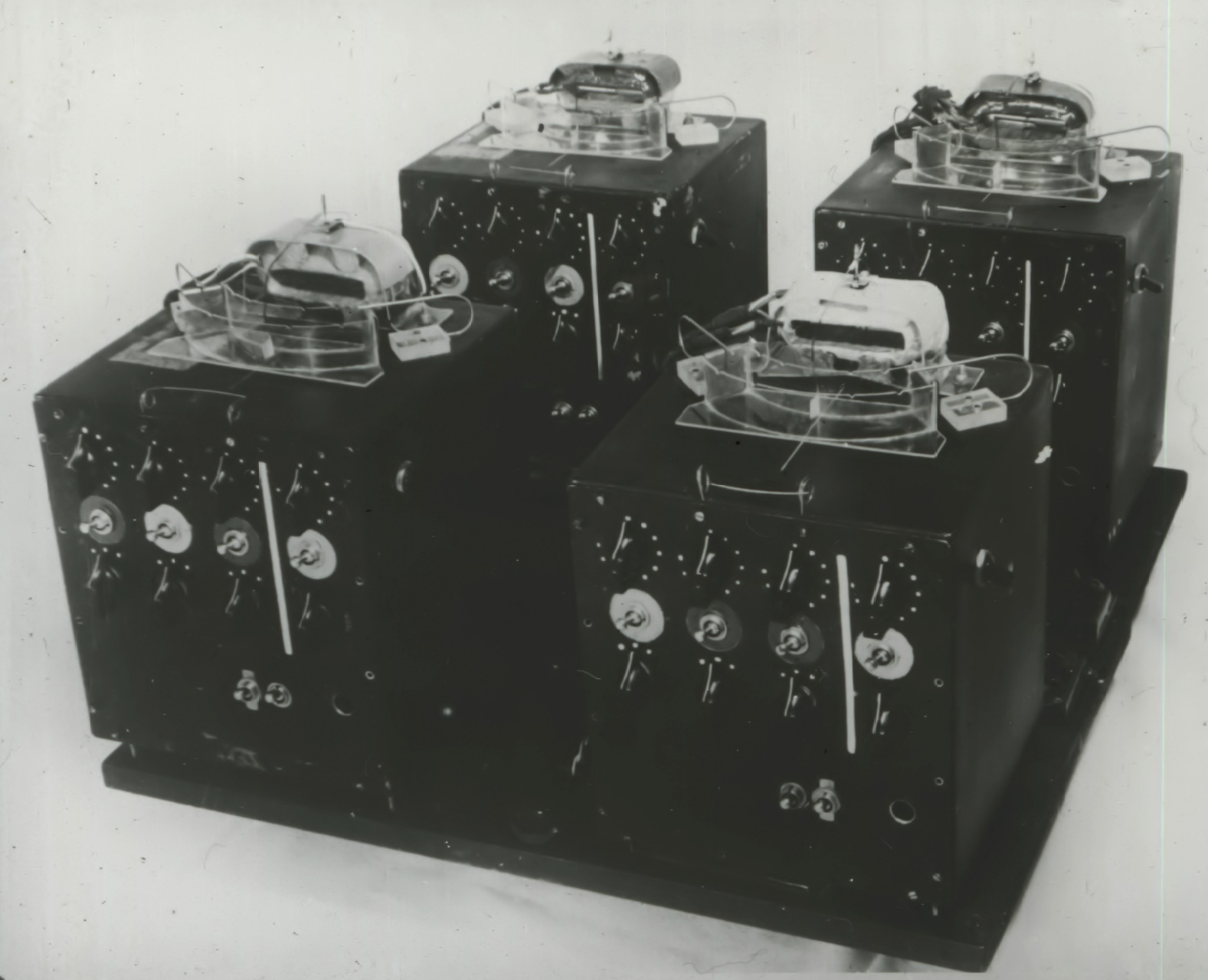

W. Ross Ashby, photograph of the homeostat, 1948

Innenansicht

Inspired by Ashby’s homeostat and Wiener’s discussion of brain waves as existing in a perpetual state of equilibrium, Cerha’s Netzwerk makes stability the focal point of the musical and plot progression. Cerha was already artistically exploring such topics in the orchestral work Fasce, though that work remained embedded in a unified and uniform musical language. Netzwerk, however, dispenses with this allegiance to a specific style; dissimilarity dominates the various levels of mutual influence in the piece.

As in Exercises, two layers in particular can be distinguished: main movements and what Cerha termed “regresses”. In the main movements, Cerha usually presents a largely stable order, which, must prove itself again and again against hostile forces that stem from the intervening regresses. The “regress” layers most closely symbolise what cybernetic theory would term the “environment”: a sphere that exists in contrast to a regulating system and can have a disruptive effect on it. Cerha similarly embraces the opposing forces in Netzwerk:

From a technical point of view, my piece became increasingly comparable to a system made up of differently structured subsystems. Orders contradicted each other in places, and disturbances arose. The problem of how to create them began to play an increasingly important role for me. Short sections inserted between the main sections, which I called “regresses”, have this function. They are regressive in that they drop down from higher organisational levels to more primitive workings of the basic material, and are usually even more regressive in terms of style, by including traditional forms. With a semblance of immediacy, they break into the far more puristically shaped blocks of the main movements.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 233

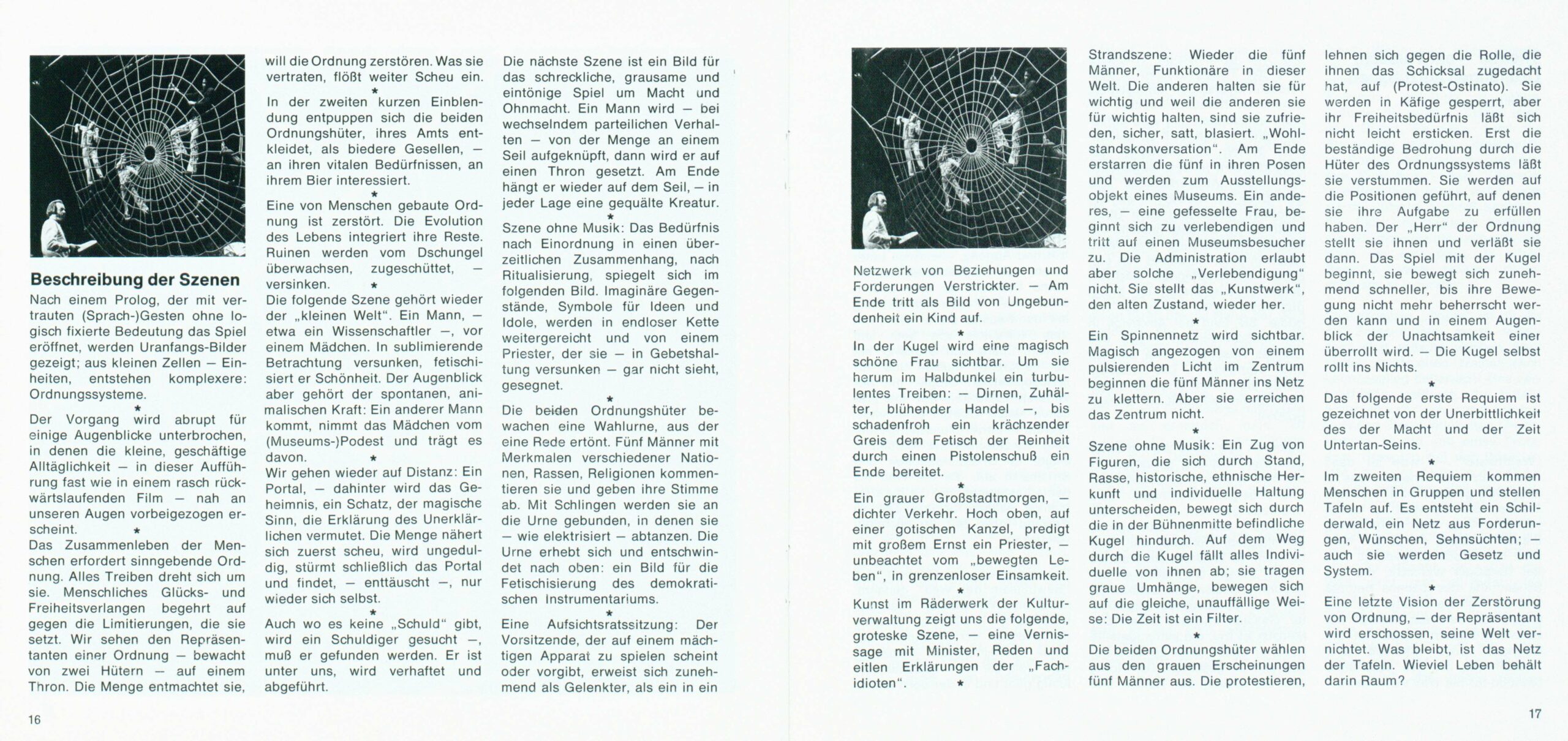

Netzwerk is a kind of Theatrum Mundi—a stage where humanity presents itself as a species. As in the musical progression, no story unfolds and no individual destinies develop. The basic situation, repeatedly referred to, is the relationship between life, which must develop, and order, which strives to preserve itself. The mass of “humanity”, uniform in behaviour when seen from an infinite distance—like a nation of insects—creates orders out of sheer necessity, and is also subject to them. The “human” superstructure: Orders are arbitrarily directed, submission is demanded, and, following a primal need, order systems are justified by a higher meaning. Political, religious, and humanistic structures of power and dominance are the logical derivation of this. Humankind rubs up against them—producing them again and again. Systems contradict each other, influence each other, dissolve or replace each other.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 236

“Order” and “systems of order”: These terms are found in Cerha’s descriptions of Netzwerk again and again. Regarded from a socio-political perspective, they conceal domination and oppression. The cybernetic reading is that systems need regulation in order to reach goals. It is typical of Cerha’s approach to look for the system’s true strength in the constant disruption of order, in the questioning of stability. Significant aspects of this approach can be traced back to Ashby. Flipping one of the external switches on the homeostat initiates a balancing act. The wires on the four blocks, connected to magnets, begin to move uncontrollably, and electromagnetic rotary selectors inside the blocks search for new positions. Stillness does not return until these new positions are identified. Once a new equilibrium is established, the four wires finally come to rest in a central position. What seems to be a technical feature of the homeostat actually has great significance: The ability to cope with new and unpredictable situations is a key survival skill. The homeostat behaves like an organism, surviving and overcoming crisis. Ashby termed this “ultrastability”. The extent to which Cerha used this concept as a jumping-off point becomes clear when one compares the systems of Exercises and Netzwerk with “multistable systems in the field of biology“.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 63

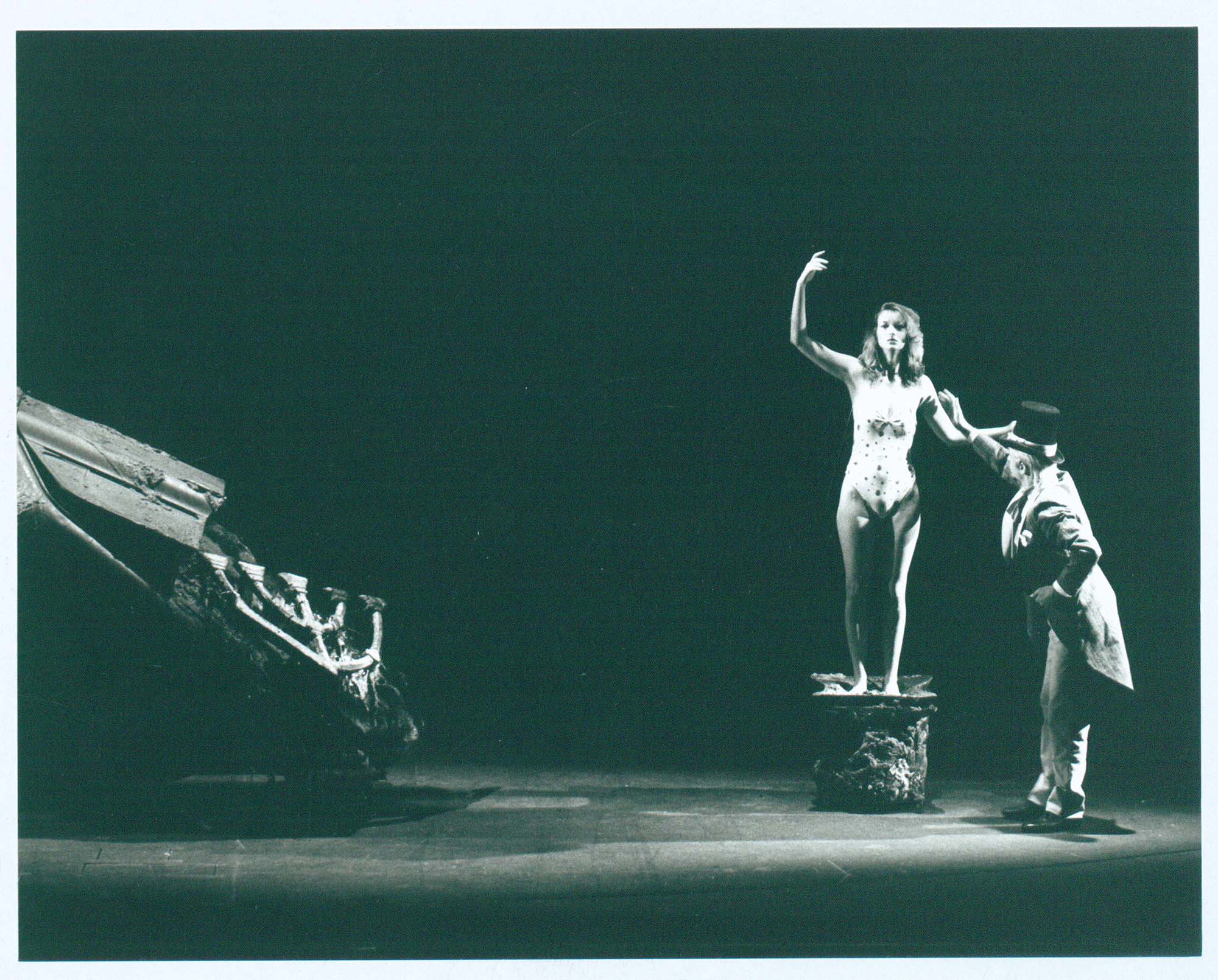

The changing levels in Netzwerk’s theatrical concept are part of the idea of multi-stability. Constant changes in musical and visual types of expression permit the flexibility necessary to realign classification systems. Stylised figures in the theatrical scenario make orientation possible: Representatives of power are, for example, the baritone (in different roles) and anonymous enforcers of order. They are contrasted by a naked female figure who appears in various scenes and is treated almost like an inanimate object, and by five speaking roles, which are assigned to different (yet not precisely defined) cultural areas through their specific patterns of speech. A large, floating sphere becomes a symbol of world events.

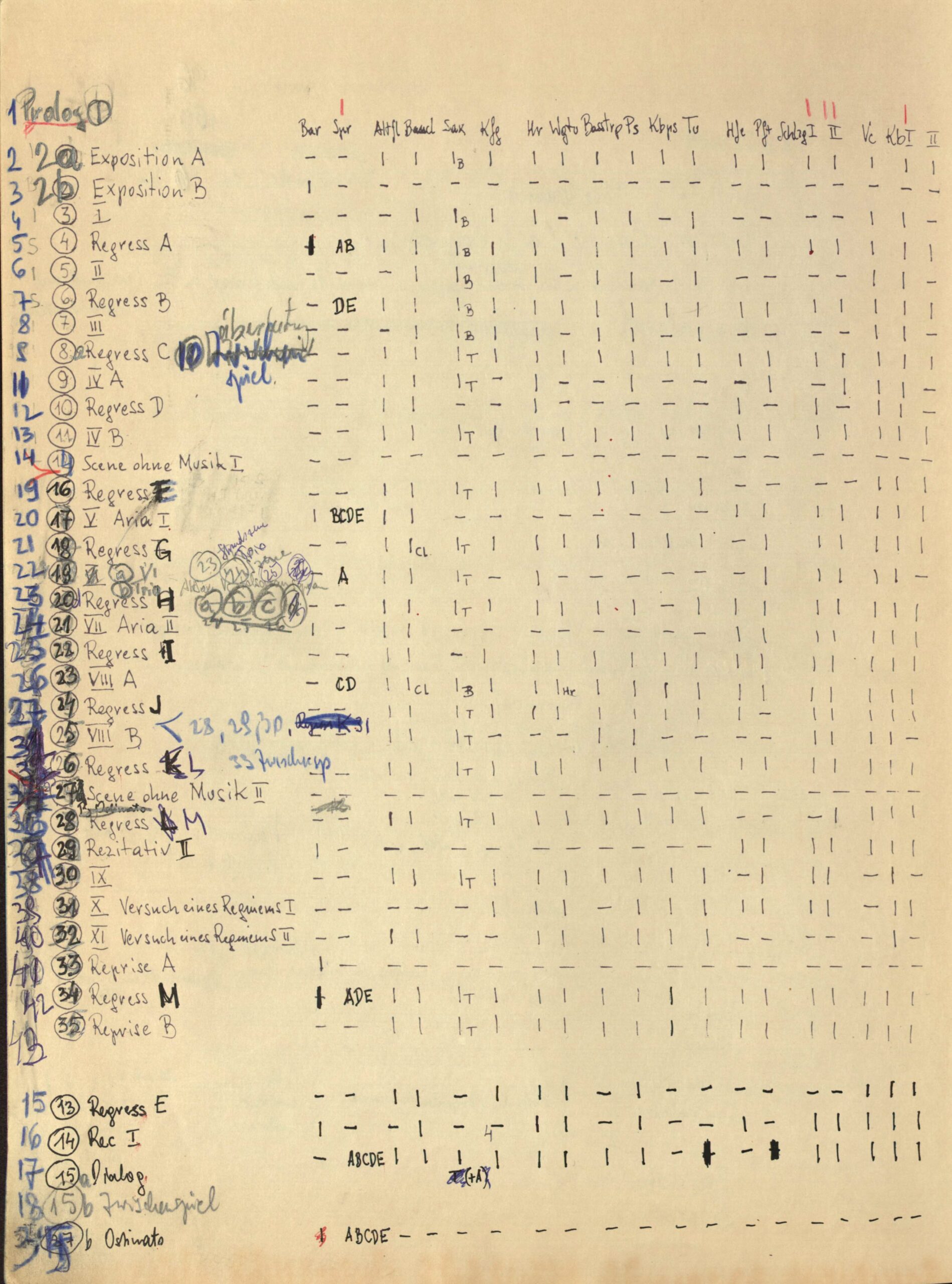

Programme booklet Netzwerk, Wiener Festwochenl 1981, AdZ, KRIT003/11

The various stations of Netzwerk—44 in all—can only to a limited extent be seen as examples. Every section contains changes, and the constantly interweaving relationships of the levels mean that no one order can return a second time. Nonetheless, individual features of earlier orders are sometimes retained over long periods, given a fresh appearance within each new context. Over the span of the work, Cerha’s poetry transforms the musical arrangements of the main movements, adapting to the circumstances so fully that they are eventually changed entirely. These organisational changes can be understood by looking at a few selected examples of the stages of development.

The first movement represents fertile soil for the gradual establishment of order. After nebulous events in two expositions, structures gradually develop on stage. Starting with a dark lighting ambiance and a barren environment, people in uniform gradually bring life to the stage. In line with Cerha’s vision, they act as a kind of “nation of insects“,Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 236 drawing from a metaphor for social structures that has been used for human societies since antiquity. Symbolic of the formation of order, radiant green web structures repeatedly appear in the background of the stage sets. The music also follows these developments from amorphous and vague to sometimes recognisable shapes. Initially shrouded in dark, impenetrable soundscapes, there are flashes of increasingly accentuated and often sharp fragments of sound as the music unfurls. Gradually, the dense network of sounds begins to loosen. A certain stasis, however, is also characteristic of the music. The sound gesture slowly feels its way forward, unchanging, and the music carefully progresses through various mini-sections, separated from one another by pauses. There are changes in the details between them, but Cerha consistently sticks to the same soundscape organisational system. Something essential emerges from the movement’s broad and leisurely unfolding: The music for Netzwerk is not actually stage music, is not primarily dramatic and visual, as in Cerha’s operas. The main movements in particular use an abstract tonal language that is part of the highly experimental zeitgeist of the 1960s.

Produktion Wiener Festwochen 1981, Theater an der Wien,

Inszenierung: Giorgio Pressburger,

Choreografie: Ivan Marko,

Ensemble „die reihe“, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha

The regress that follows the first movement abruptly tosses the existing system of musical order overboard. No longer does Cerha arrange the tonal material of these suddenly erupting miniatures using delicate soundscapes, but instead in swarms of fast, dry, overlapping semiquavers. This superimposition makes the individual figures difficult to filter out—instead, the listener experiences higher-level tonal movements. These begin in the lower register, mainly with the bass instruments of the first movement, and gradually move up, ending with a skeletal cacophony of piano, marimba, and vibraphone. The illustrious hustle and bustle of the music is joined on stage as an array of recognisable characters populate the room: The virtual camera lens that in the first movement focusses on society from afar here zooms in to allow a view from closer up.

Produktion Wiener Festwochen 1981, Theater an der Wien,

Inszenierung: Giorgio Pressburger,

Choreografie: Ivan Marko,

Ensemble „die reihe“, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha

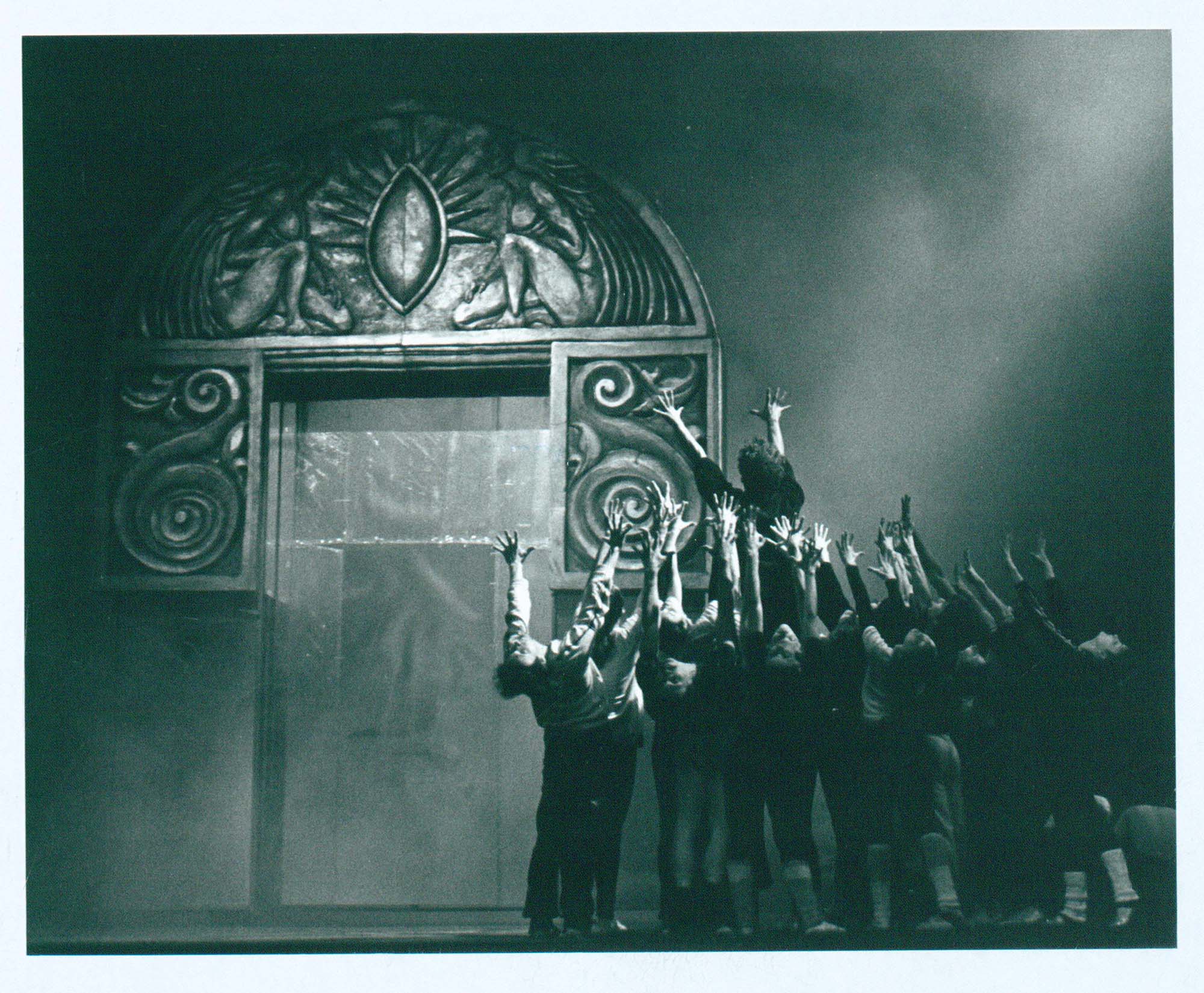

The strength with which the regresses and movements react to each other on systemic levels becomes clear in the second movement. The link between the music and its raw “original state” is clear—yet reacts to the disruptions with noticeable irritation, especially in the beginning. The fragile soundscapes are pushed almost entirely into the background, with unevenness dominating. Short notes, sharp accents, uncomfortable sound effects (the wind instruments often making use of the flutter tongue technique, for example), and enigmatic lines overlap crudely, unpleasantly. Following the cybernetic concept of regulation, planar sounds gradually return, though hasty figures repeatedly prevent them from complete restoration. The communicated potential for conflict is increased by the activity on the stage. From the beginning, the crowd stands in opposition to the ruling figure, the baritone, with the stage space divided into two clear sections that separate the people from those in power. Increasingly, however, the people are assured of their ability to change and eventually cross the dividing line—a disruption that symbolically leads to the establishment of a new order.

Produktion Wiener Festwochen 1981, Theater an der Wien,

Inszenierung: Giorgio Pressburger,

Choreografie: Ivan Marko,

Ensemble „die reihe“, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha

Cerha’s arrangement of regresses in the sequence of movements causes a gradual change in the musical order. At the end of the first part of Netzwerk is another important movement. In it, a system of order emerges that is paradigmatic for Cerha: a reference to the first of the seven parts of Spiegel, for large orchestra. The structural principles of both pieces are identical and easy to understand: Starting with isolated orchestral beats, a process of unravelling begins, soon leading to brash and almost impenetrable tonal fields. In both pieces, Cerha divides the orchestra into two sound groups, almost like a type of double canon. The competition between the two orchestral groups corresponds to the way the crowd onstage is divided into two groups. At the centre: the ruler’s throne, familiar from the second movement, a symbol of power and disempowerment. The first group of people chooses a naked man as their master, before the second group robs him of this role and—as in the beginning—hangs him from a long rope, from which he dangles until the end of the number. Seen from the musical bird’s-eye view, the replacement of the dominant deep and harsh timbres in the first part of Netzwerk with high, ethereal tones is symptomatic of the allegorical stage play. These higher tones are what remain at the end of the second orchestral section’s unravelling. A chirping tonal mixture of harp, glockenspiel, and antique cymbals in an otherwise quiet room seals the end of this particular system of order.

Produktion Wiener Festwochen 1981, Theater an der Wien,

Inszenierung: Giorgio Pressburger,

Choreografie: Ivan Marko,

Ensemble „die reihe“, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha

The closer one gets to the centre of Cerha’s Netzwerk, the more the musical systems move away from the anarchic, impulsively proliferating breeding ground in the first movement and towards the sound ideal of artificially comprehensive organisation. This principle becomes recognisable in the sixth movement, which assumes the function of a central axis. The tonal language is characterized by gestures that are astonishingly similar to Cerha’s serial composition phase. Fields of internally differentiated and complex rhythmic cells come together in blocks, or are separated, as in the first movements, by pauses of approximately the same length—causing sections of a completely different nature to arise again. On stage, an unnerving turmoil is visible around an illuminated globe, within which the allegorical naked girl re-emerges, only to be shot by a suspicious character. A dancing pair of lovers emerges from the dark scenery (Regress H)—another perspective on humanity’s “vital animalistic foundation”.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 84 The music: lyrical, velvety, and carried by broad melodic arcs. Now, the regression arrives at the vocals, completely opposite from the earlier punctuated sound groupings. Influences from the layered abstract orders of the main movements are immediately recognisable; the next movement develops one of Netzwerk’s two arias, although it might be more appropriate to call it a distortion of an aria. The baritone stands like a priest on a kind of pulpit, beneath him fluttering the urban bustle of various people. This stylised emotional image, which arises from the artificial language that Cerha invented for Netzwerk, is sharpened by graceful, almost wafer-thin and crystalline chord sequences. These can be viewed as remnants of the isolated beats that characterize the beginning of Movement IV B, but here they fit into an entirely new context that no longer has much in common with the originally natural unravelling. Here, the system of order has reached a manneristic point of elaborate tonal embellishment—a point from which development must, and does, proceed in other directions. Allusions to earlier systems of order become more noticeable in the following sections, sound states that had been left behind return in modified form. In a certain respect, these reflect the impossibility of complete control—the cybernetic vision of perfect regulation is revealed to be just an illusion.

Produktion Wiener Festwochen 1981, Theater an der Wien,

Inszenierung: Giorgio Pressburger,

Choreografie: Ivan Marko,

Ensemble „die reihe“, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha, Peter Binder (Bariton)