The Conductor

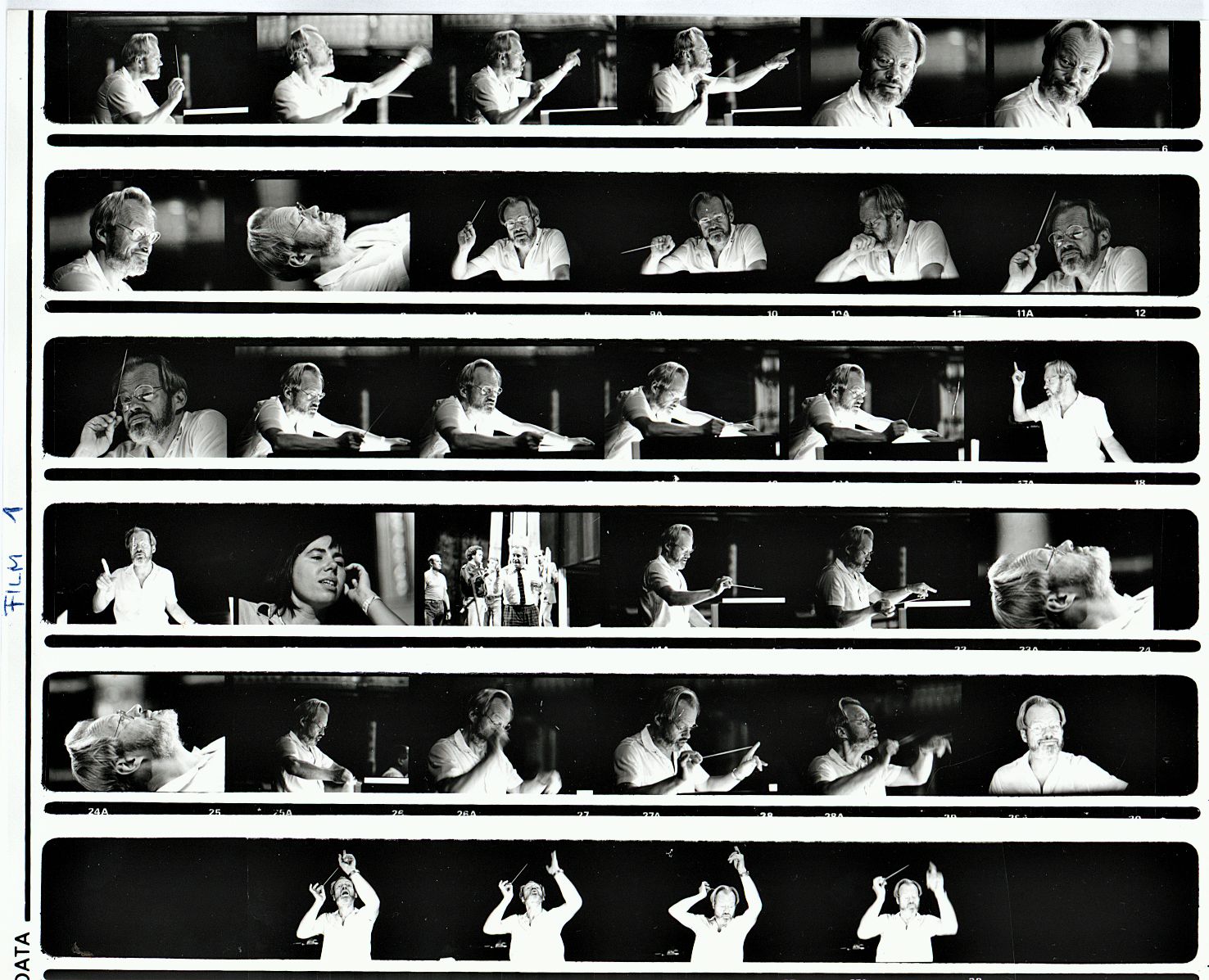

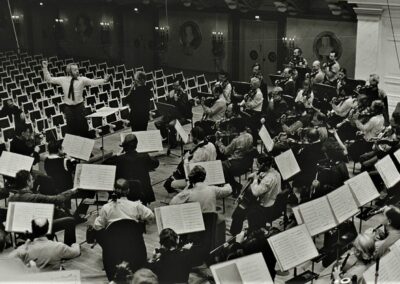

Cerha at the conductor’s stand, Graz Opera 1981

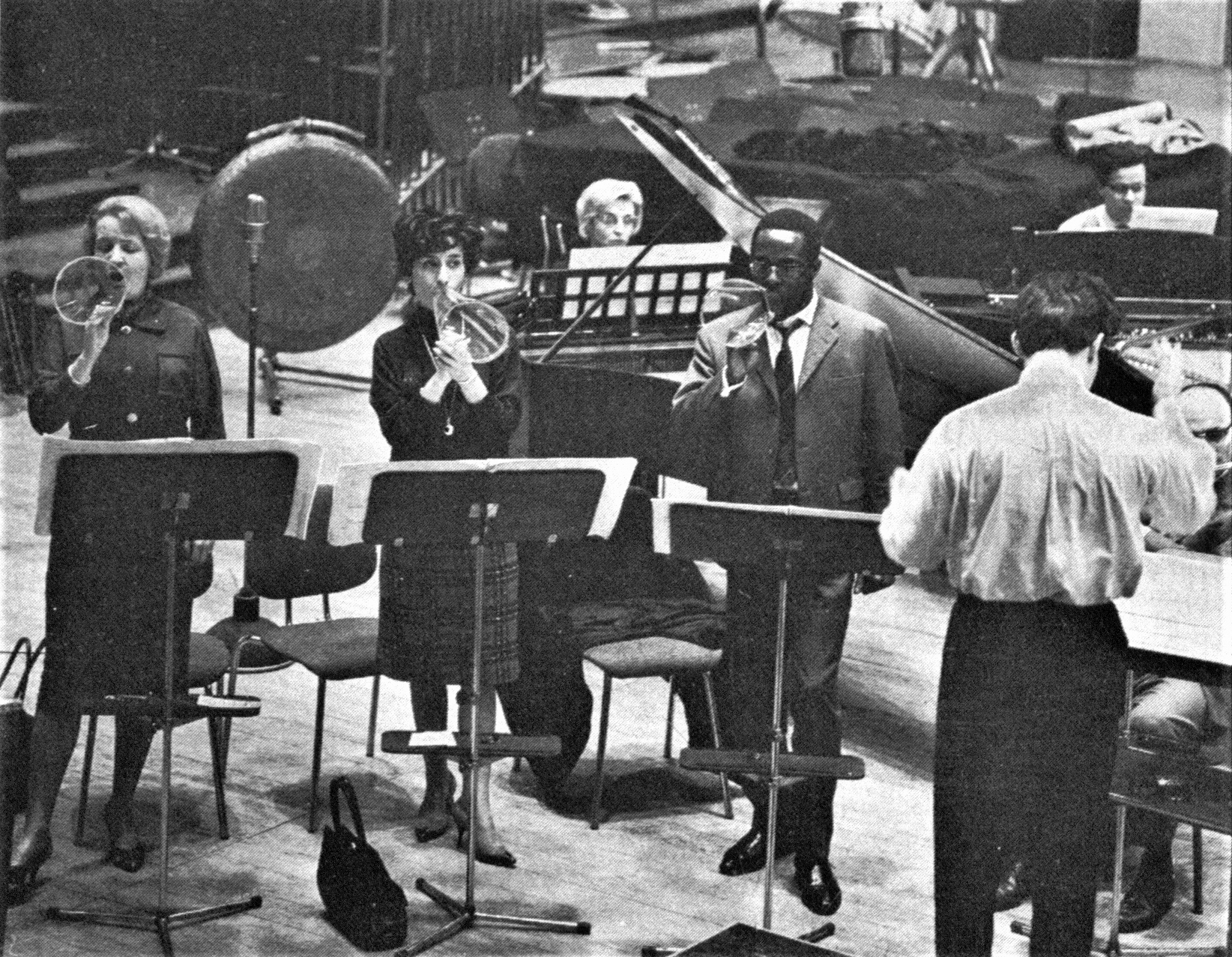

At the intersection of composition and conducting, Cerha performed his completed version of Alban Berg’s opera Lulu for the first time in Austria in September 1981. The meticulousness of his reconstruction went hand in hand with the way he rehearsed the music. The photo shows Cerha at rehearsal.

Image source: The Archives of Contemporary Arts

Composers conducting, conductors composing: this once was a matter of course. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart conducted the orchestra from his seat at the harpsichord. Jean-Baptiste Lully, the court composer of Louis XIV, the “Sun King”, once accidentally rammed his conductor’s baton into his foot—an incident that ended with his death. In 1817, Carl Maria von Weber started using the baton as we know it today. Previously, conductors often used a rolled-up sheet of staff paper. The question of which of the two professions—composing or conducting—was more important did not seem to matter, as the two activities often went hand in hand. However, there were hierarchies to be found here and there. Richard Wagner, for example, was a passionate conductor of Beethoven’s symphonies and was greatly admired for it by his contemporaries. But in essence, Wagner saw himself as a composer. Leonard Bernstein wrote works that are part of our repertoire today—just think of West Side Story, for example—but his primary focus was always behind the conductor’s stand. His performances of Gustav Mahler’s symphonies are unforgettable. The fact that he sympathised so greatly with Mahler is also telling, as he, too, exemplified the conflicting life of someone who was both composer and conductor.

There have been only a few high-ranking artists since Mahler who have undertaken the balancing act between conductor’s podium and writing desk. Friedrich Cerha is one of them, and this in an era of specialisation that did not leave the world of music untouched. The experiencing and shaping of music from multiple perspectives was always part of his very essence. As a violinist, as a conductor, and as a composer, he encountered music in many facets. At times, his work as an orchestral conductor dominated the public perception.

His Own Ensemble: “die reihe” and How He Got There

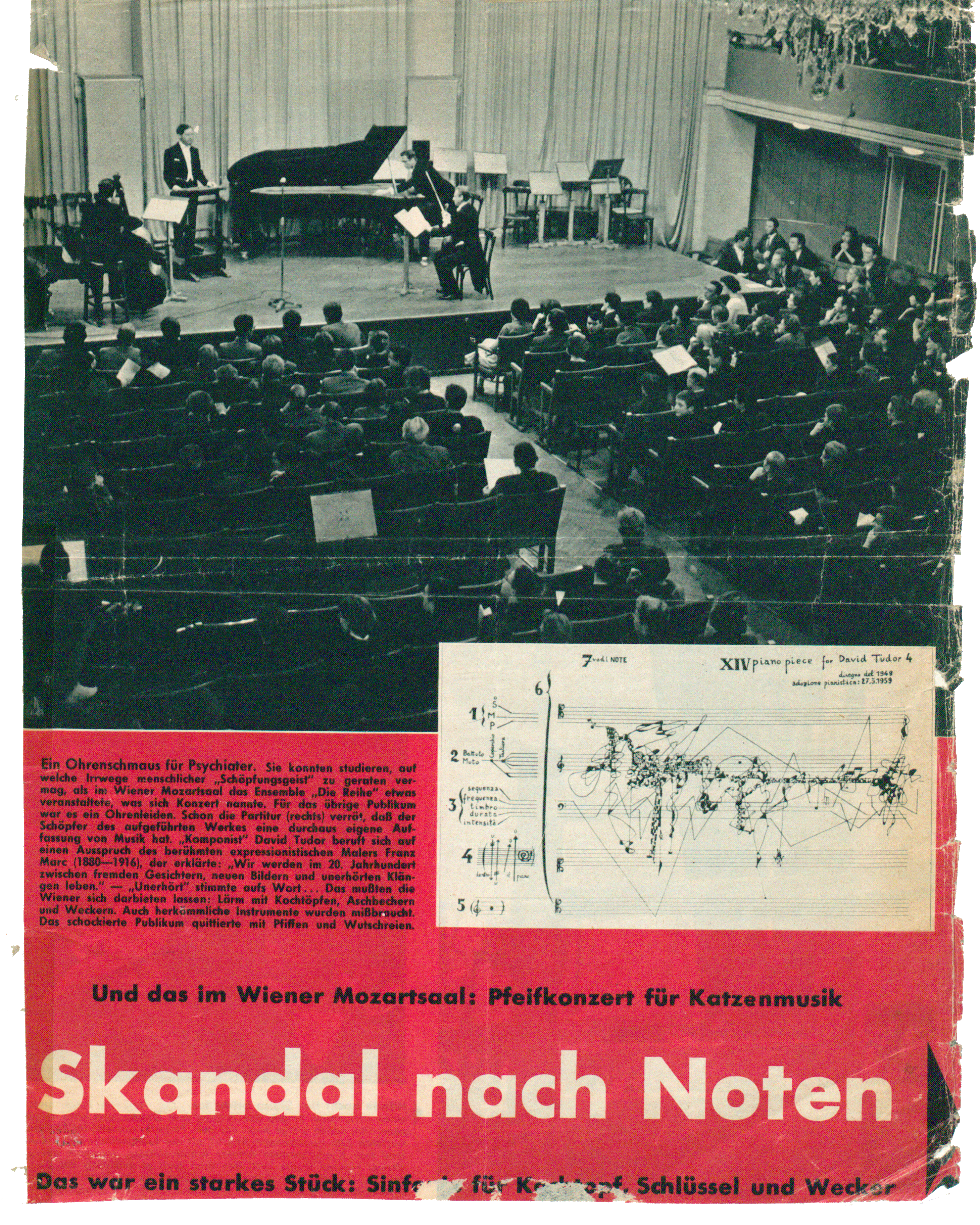

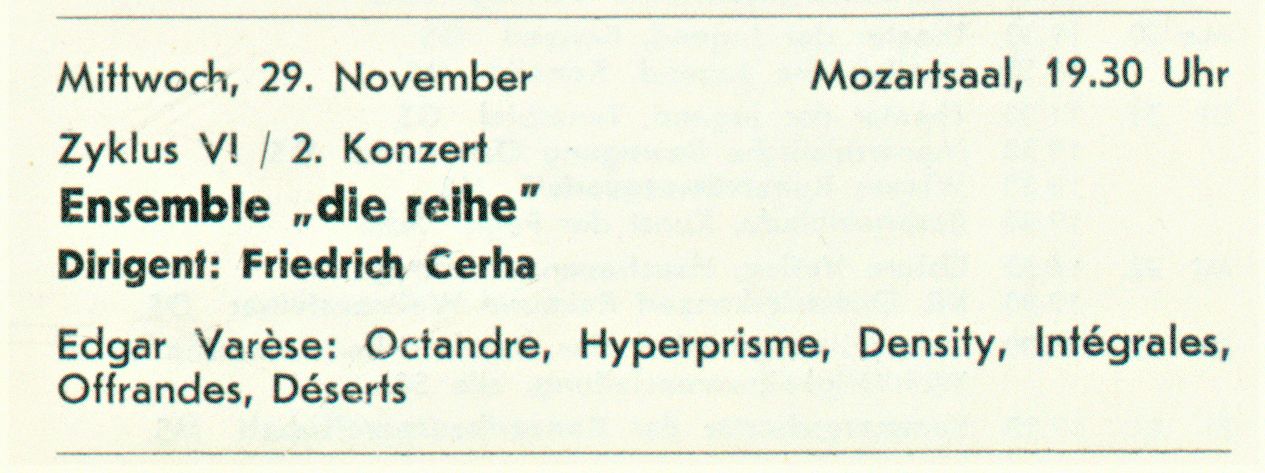

However, without a doubt the first concert of “die reihe” was the beginning of a success story. By as early as the third concert, the Schubert Hall was no longer large enough to satisfy audience demand. Concerts were then moved into the larger Mozart Hall, where one of the ensemble’s most sensational concerts was held in November 1959. The program was made up entirely of aleatoric works—that is, works that consciously included the element of chance. While Cerha conducted Christian Wolff’s Music for Merce Cunningham for six to seven players, Schwertsik directed the performance of John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra, an essential work of chance operations in music. “The concert,” said Cerha, “sparked the greatest scandal since the end of the Second World War. All the newspapers were full of pictures of Schwertsik showing the time with both arms outstretched like a clock, while hiding himself from the throngs of onlookers on the street at my place on Salzgries.”Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Wien 2001, S. 36

Not only did the Cage concert ignite public interest in the activities of “die reihe”, it also achieved the ensemble’s aim of bringing the very latest (and not just vaguely current) pieces to Austria’s music program: The premiere of the Concert for Piano in New York and the European premiere in Cologne had taken place just that previous year, for example. Staying current and in step with the Zeitgeist remained a fixed point in the years that followed, securing “die reihe” and thus also Cerha, the conductor, a permanent place in Viennese cultural life. The Wochen-Presse described the concert series of 1960/61 as “avant-garde by subscription”.

Performances and Premieres—Nationally and Internationally

Konzerthaus news, announcement of a Varèse concert, Wiener Konzerthaus, November 1961, AdZ, KRIT009/38

Edgard Varèse, Ameriques (excerpt)

ORF orchestra, conducted by Friedrich Cerha, 1976

Aventures, a milestone in avant-garde language composition, was undoubtedly one of the most spectacular premieres of “die reihe”. On 4 April 1963, it was performed in Hamburg for the first time under Cerha’s direction and soon (together with its “twin”, Nouvelles Aventures) became part of the ensemble’s core repertoire.

Rehearsals for Ligetis Aventures and Nouvelles Aventures, Hamburg, May 1966.

György Ligeti, Aventures

Ensemble “die reihe”, conducted by Friedrich Cerha, 1968.

Even in light of his success abroad, Cerha stayed true to “die reihe”. Together with the ensemble, he helped Ligeti’s Kammerkonzert (1969/70) see the light of day, and also helped other colleagues to premiere their works, among them: Krzysztof Penderecki (Dimensionen der Zeit und Stille, 1961), Anestis Logothetis (Parallaxe, 1961), Istvàn Zelenka (Adaptionen, 1964), Roman Haubenstock-Ramati (Multiples, 1969), HK Gruber (Vertreibung aus dem Paradies, 1969), Jungsang Bahk (Seak I, 1971), Ernst Krenek (Von vorn herein, 1974), Bojidar Dimov (Bewegliche Signallandschaften, 1975), Luna Alcalay (New Point of View, 1975), and Dieter Kaufmann (Boleromaniaque, 1976). Countless Austrian premieres testify to Cerha’s great service to the musical culture of his home country, including: Arnold Schönberg’s Drei Stücke für Kammersensemble, Claude Debussy’s Les Chansons de Bilitis, Erik Satie’s Le Piège de Méduse, Charles Ives’s The Unanswered Question, Luciano Berio’s Tempi concertati, Iannis Xenakis’s Atrées, Morton Feldman’s The Straits of Magellan, Witold Lutosławski’s Paroles tissées, and Alfred Schnittke’s Konzert für Violine und Kammerorchester.

Claude Debussy, Les Chansons de Bilitis (excerpt)

Erik Satie, Le Piège de Méduse

Ensemble “die reihe”, conducted by Friedrich Cerha, 1968

- “The ‘die reihe’ ensemble will play four concerts in the Mozart Hall during the 1967/68 season […].

- For the 1968/69 season, the ‘die reihe’ ensemble will perform a representative cycle of works to mark its ten-year anniversary, a cycle that provides an overview of what has been achieved during this time and, with this cycle of performances, is discontinuing its activities at the Wiener Konzerthausgesellschaft.

- As part of the 1969 Wiener Festwochen, Dr. Cerha will begin a new phase of his professional life, with a large orchestra concert, which will make it possible for him to break out of the confines of chamber music and to begin performing as an interpreter of modern music for normal orchestral concerts.”

Cerha categorically rejected Weiser’s proposal to discontinue “die reihe” and break up the ensemble in order to grow his career as an orchestral conductor. In a letter dated December 1967, he accused Weiser of “typically dictatorial power politics”:Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Wien 2001, S. 56 “One simply does not make ambiguous proposals to a conductor.” Although this conflict did not lead to a break between the Wiener Konzerthaus and “die reihe” and its conductor, their activities did change. While they had already played in alternative venues in Vienna in previous years, such as the Museum of the 20th Century or the ORF broadcasting hall, starting in 1968 the ensemble increasingly performed on international stages, for example embarking upon a major tour of America.

Cerha as a Conductor

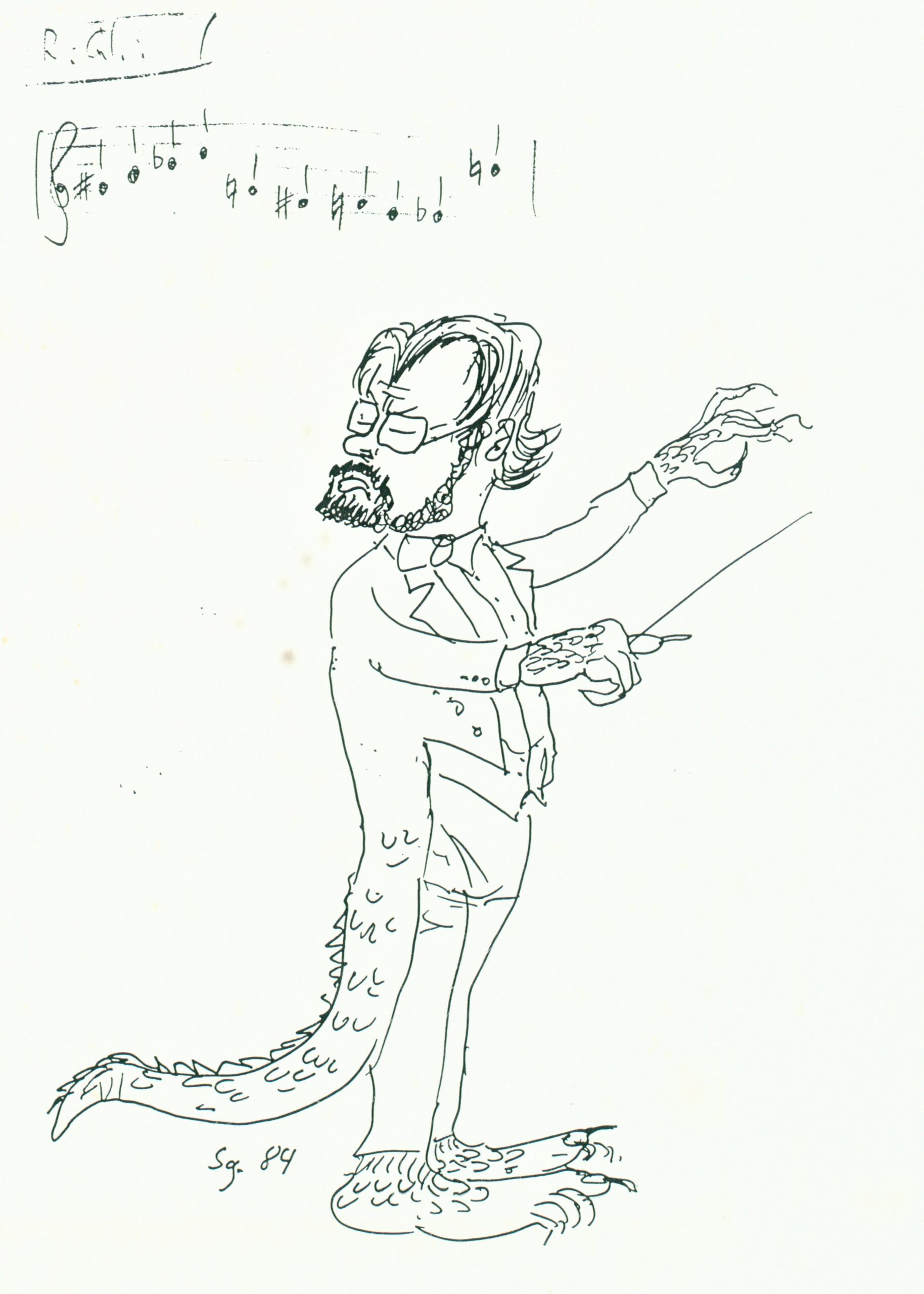

Caricature of Cerha as a conducting Ichthyosaurus.

Two whimsical caricatures from the early 1980s show Cerha at the conductor’s desk as a hybrid of human and dinosaur. But what do they reveal about him as a conductor? The name “Ichthyosaurus” can be read on the desk. If one knows anything about how the ichthyosauri that swam the oceans of the Mesozoic looked, the caricatures become even more irritating. Apart from the baton, which resembles the pointed snout of the prehistoric reptile, Cerha’s dinosaur tail and clawed hands and feet have nothing in common with those of the prehistoric creature. If, on the other hand, one digs further into his oeuvre, the irritation is resolved. The animal moniker is a play on the “Ichthyosaurus Parable” in Bertolt Brecht’s play Baal, the basis for the text of Cerha’s opera of the same name. In it, Baal tells of Noah’s Ark and how the Ichthyosaurus refused to enter the ship and gain safety from the flood. A symbol for the entire opera, the story describes the stubbornness of an individualist refusing to adapt to society, instead striving to placate the needs associated with his own being. One could conclude that the caricatures subtly convey a message about Cerha’s will, about his refusal to be bent into a purely business-minded orchestra conductor. His interest in promoting music that had difficulty finding a place in the commercial music scene indeed runs throughout his entire conducting career. The message of the caricatures thus also contains a cultural and political component. On the other hand, the drawings also reveal something about Cerha’s unique way of conducting. His gaze is stoic and unwavering, focused on nothing other than the music itself; this is one way to interpret the message.

Cerha dirigiert ein Stück von Anton Webern (vermutlich Zwei Lieder nach Rainer Maria Rilke op. 8) mit der Sopranistin Adrienne Czengery, Madrid 1983

The silhouette of a conductor is usually a reflection of the people who stand behind him. Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss, for example, belonged to the same era, yet their conducting techniques were profoundly different. While Mahler was extremely gestural, with large and sometimes even chaotic movements, Strauss was more of a minimalist—which Cerha had experienced in person himself:

In 1944, I was on leave from the military when Richard Strauss celebrated his 80th birthday in Vienna. I went to the opera or to a concert every single day. He was standing in front of the building during an intermission of Frau ohne Schatten, and I observed him from a distance as if he were a timeless monument: It was unbelievable to me that all this music could have emerged from this head. At that time, I also saw him conducting his Sinfonia domestica and admired his extremely economical, entirely unspectacular movements.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Wien 2001, S. 27

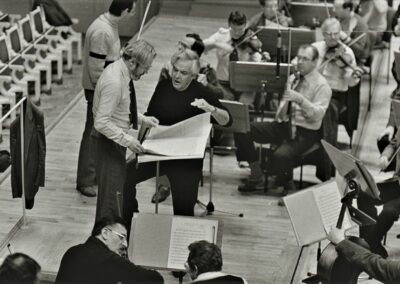

It is difficult to say whether these impressions rubbed off on Cerha’s own conducting style. An assimilation of Strauss in the sense of his sparse movement style can certainly be ruled out. The complex works that Cerha had directed since his early days demanded precise clarity and unmistakable guidance—whether due to complicated time changes, tricky vocal interludes, or aleatoric moments that required intense communication. On the other hand, in Cerha’s early appearances his style was far from the theatrical movements à la Mahler. In any case, he was committed to a precisestyle of conducting that served only the purposes of the music, as HK Gruber remembers in looking back on the 1960s:

At that time, Cerha had developed a style of conducting that was “anti-show”. While the success of other conductors was clearly due to their gymnastic exertions, he never felt compelled to conduct music occurrences such as a reversal while doing somersaults. Despite his refusal to use traditional musical gestures, enthusiasm was evident on all levels—there was hardly anywhere in Vienna where audience interest was more vivacious, and some enthusiasts spoke of “die reihe” concerts as being the Philharmonic of modernity—overlooking the intrinsic contradiction in the compliment for sheer excitement.

Heinz Karl Gruber

„Friedrich Cerha: Vollblut mit Maske“, Programmheft zu Netzwerk, Wiener Festwochen 1981, S. 4-7, hier S. 5, AdZ, KRIT003/5

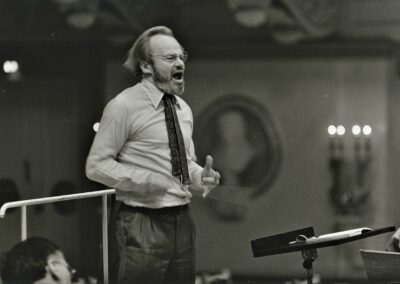

But this evidence of analytical sharpness and musical objectivity still do not create a full picture of the conductor. Cerha’s orchestral conducting was as highly diverse as his composed works. It would be wrong to paint a picture of him as nothing more than a sombre “hard-working man”: He is also impulsive and passionately expressive—only, however, where the musical texture calls for it. His grander gestures are particularly useful when working with symphony orchestras, as can be seen in a recording of a rehearsal of Anton Webern’s Passacaglia in D minor. The late Romantic orchestral line-up and the powerful swells of the piece call for a conductor with matching force.

Another good example of conducting with temperament: Cerha’s own Baal-Gesänge. These, too, are filled with an enormous range of expression and a multitude of dramatic eruptions. Conveying them appropriately as a conductor sometimes calls for extravagant gestures. Cerha performed the cycle several times with Theo Adam interpreting the vocals. However, he conducted his own operas just a single time: at the world premiere of Der Rattenfänger.

Rehearsals for Baal-Gesängen with Theo Adam and the Staatskapelle Berlin, Konzerthaus Berlin, 1987

Cerha, Baal-Gesänge, Nr. 1 ("Ichthyosaurus-Parabel")

RSO Wien, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha, Theo Adam (Bass), Produktion ORF 2006