Baal

Baal

Der Aussteiger

Exercises

Monumentum

Friedrich Cerha, Baals Frauen, 1964

In the early 1960s, Cerha became interested in Brecht’s Baal as more than a text and musical template, even creating paintings inspired by the material. His abstract painting Baals Frauen contemplates the fate of the female characters in the drama, with the maltreated souls conveyed as a deformed relief. The material itself has a very special expressive quality. In 1968 Cerha observed: “It has been hanging outdoors for several years; the colours are splintering, fading, the wood is weathered, it is returning to nature: Baal is sinking, Baal is dissolving.”

Source: Archiv der Zeitgenossen

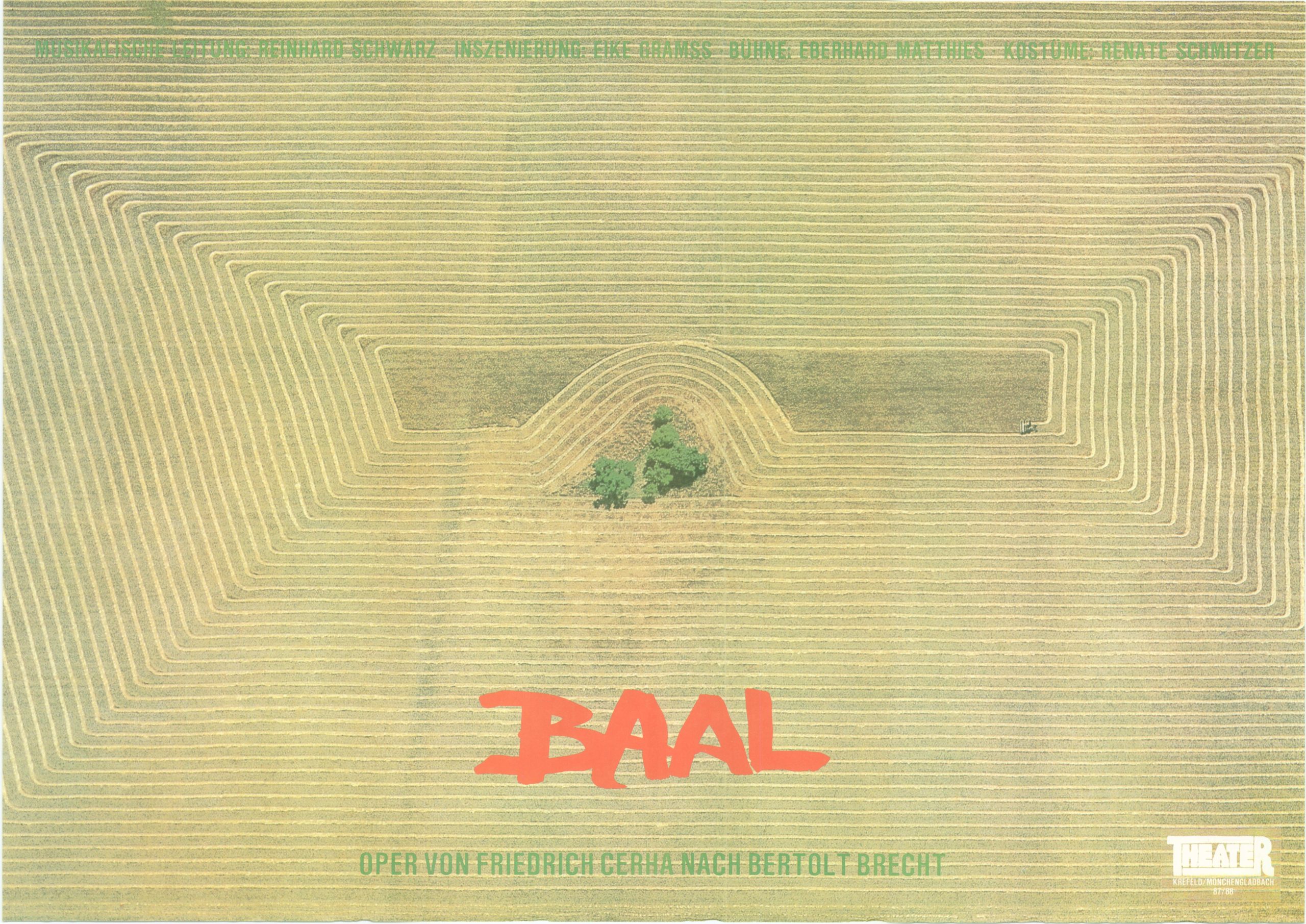

The tension between humans and nature—

this is one of the greatest themes in Cerha’s opera Baal. Baal.

Außenansicht

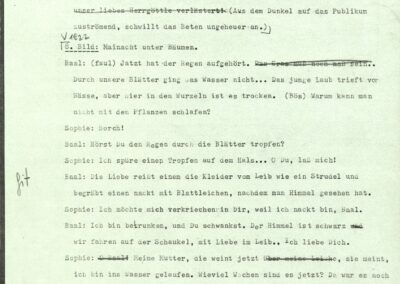

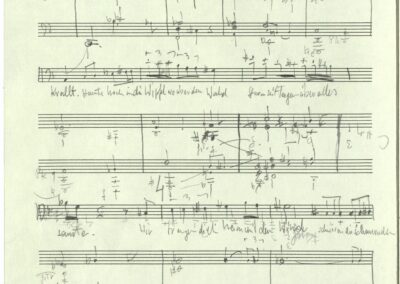

Cerha, Baal-Gesänge, 1981, Sommerlied (Ausschnitt), AdZ, 00000083/56

Cerha, Baal-Gesänge, Nr. 3 ("Sommerlied")

RSO Wien, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha, Theo Adam (Bass), Produktion ORF 2006

Cerha’s own closeness to nature is one of his most defining traits.Lothar Knessl, „Versuch, sich Friedrich Cerha zu nähern“, in: Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 10 His identification with Baal’s basic need to merge with the cosmic totality of nature, to become a single living entity, is one of the central experiences that brought the opera to life. It ties in with the existential natural experiences that Cerha enjoyed in the seclusion of the Alps after deserting the army during World War II. His later student Georg Friedrich Haas wrote about how these deeply personal experiences permeated Baal :

Much later, in the opera Baal, he will sing out about the energy of natural forces. No—it is neither a romantic alpine symphony nor music about peaceful groves and meadows. But I still remember today how mysteriously deeply those scenes of Baal touched me at the premiere in 1981. I could feel it: It was the voice of someone who had experienced nature not as a tourist, but who felt and suffered from nature as the only means of survival.

Georg Friedrich Haas

„Ohne ihn wäre ich ein Anderer geworden. Friedrich Cerha zum Geburtstag“, essay for the Klangforum Wien, https://issuu.com/klangforumwien/docs/agenda_2015_2016.

Brücke

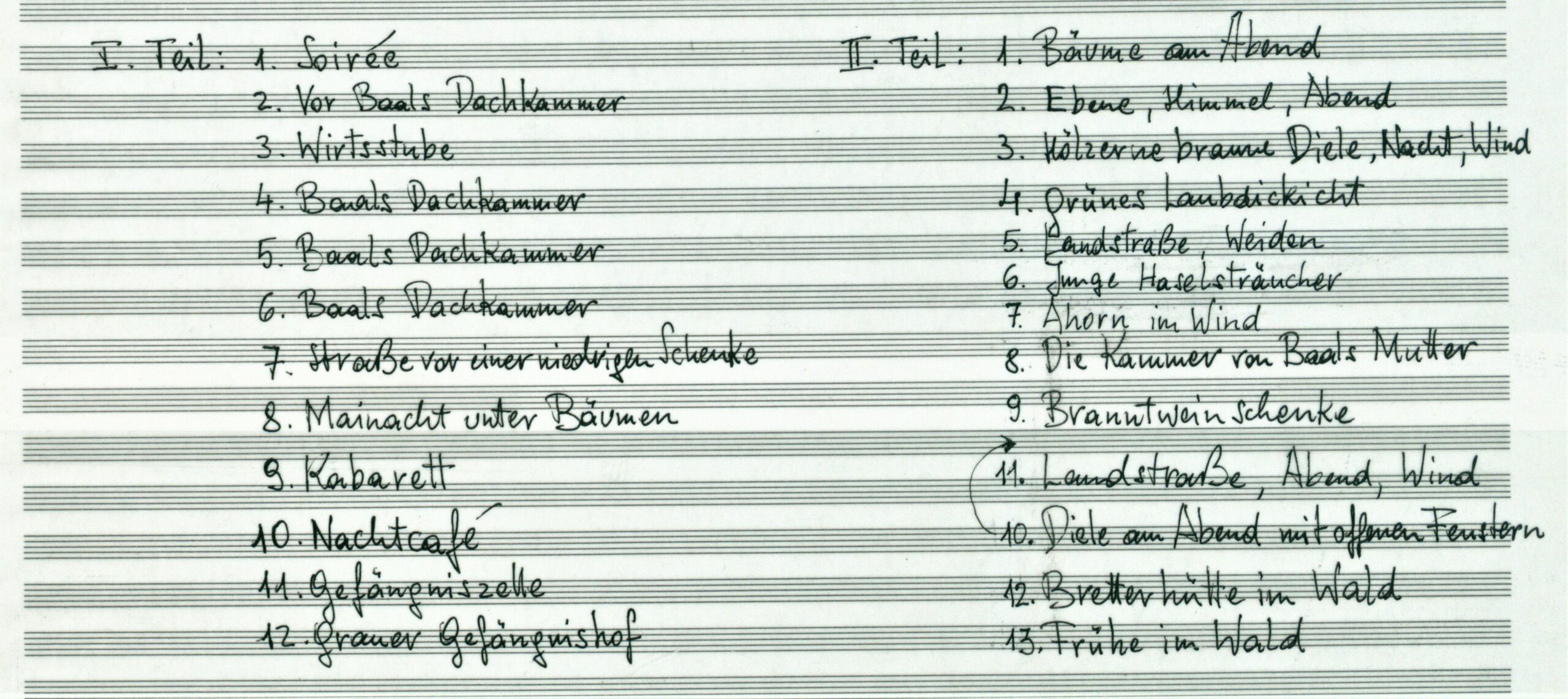

Baal, , Brecht’s first drama, is not merely a text, but a body of texts made up of five different versions. The young writer penned the first version in 1918, only to revise it into a second version just one year later. Three more versions followed, the last of which was not finished until 1955, a year before Brecht’s death. Cerha’s desire to make a musical composition out of Baal meant that he had to abridge the text. Instead of deciding to use just one version, however, he incorporated elements from all versions into his libretto. By bringing the episodes of the drama closer together, he tightened „Brecht’s loose dramatic laces“Barbara Zuber, „Herausforderung ‚Baal‘ – Friedrich Cerha und Bertolt Brecht“, in: Matthias Henke & Gerhard Gensch (Ed): Mechanismen der Macht. Friedrich Cerha und sein musikdramatisches Werk (= Schriften des Archivs der Zeitgenossen 1), Innsbruck/Vienna/Bozen 2016, pp. 129-152, here p. 133. Cerha’s first singer of Baal, bass-baritone Theo Adam, studied the different versions while preparing for his role. In a radio interview, he talked about Cerha’s sophisticated selection of material:

Theo Adam über Brechts und Cerhas Baal

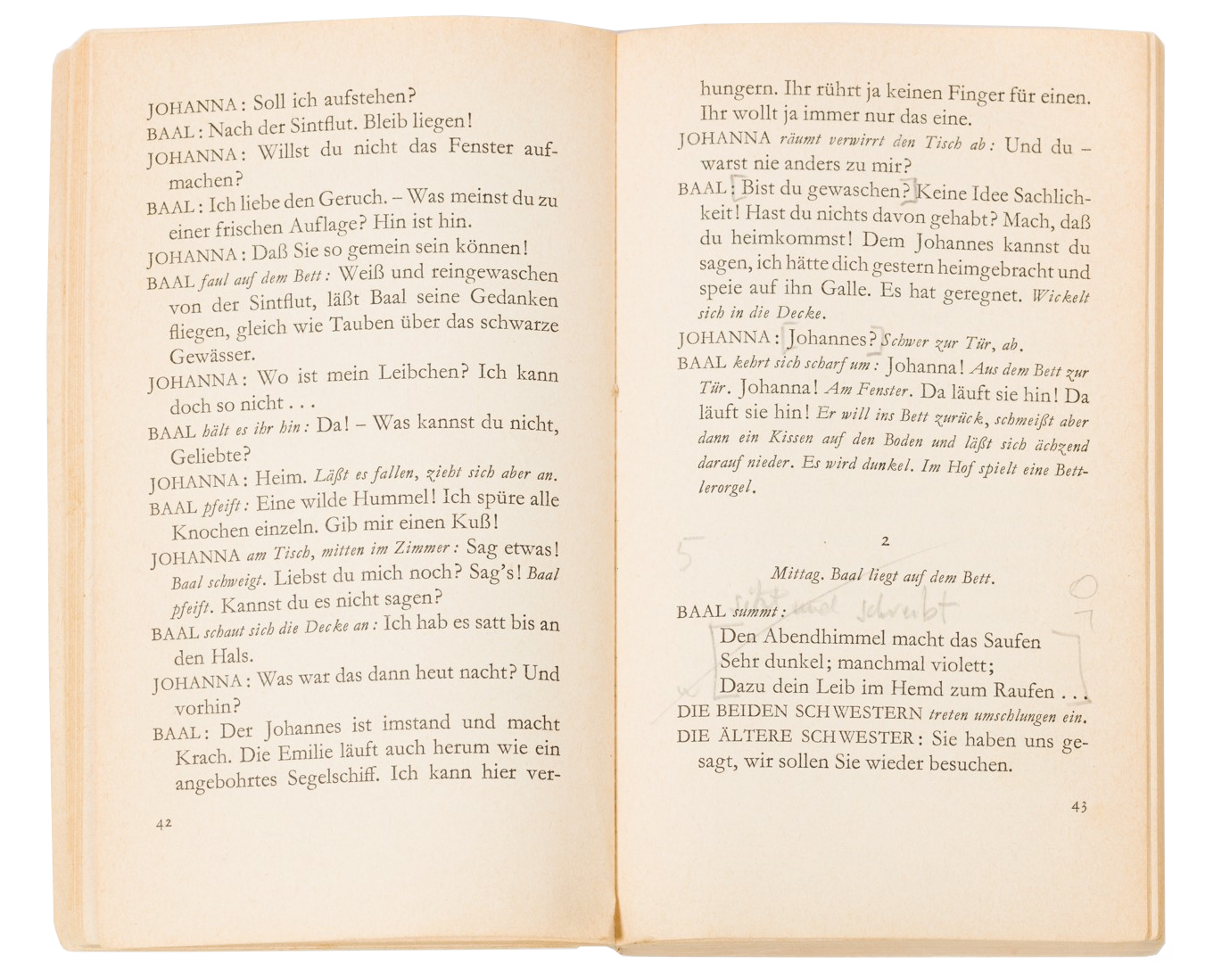

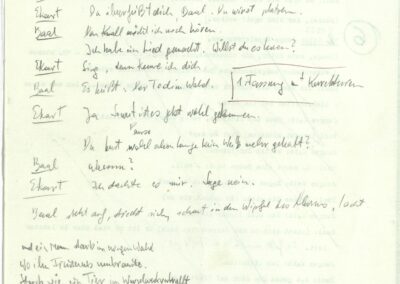

Cerha, Baal, Autograf 1981, Szenenanordnung

The nature-filled second act speaks to Baal’s longing for inner peace. Idyllic situations appear repeatedly, for example in the fourth scene, when Baal and his long-time friend Ekart lie in a thicket and watch the passing clouds from this sheltered vantage point. Still, there are indications that these emerging longings will remain unfulfilled. Baal sings about the “Country, where it is better to live” and his dream of “a small meadow with a blue sky about and nothing else”, yet these utopias turn out to be unattainable. After Baal, in a violent outburst, stabs Ekart, the forest becomes the tragic scene of his own fate. The morbid aspect of the forest escalates, culminating in Baal’s solitary death, buried, as one song describes, under “the corpses of leaves”.

Innenansicht

Cerha on the layers of music in Baal

Cerha, Radiogespräch über “Baal”, weitere Angaben unbekannt,

AdZ, CER-S1_28K

In the case of Baal, it makes little sense to strictly delineate the layers, as is fitting for example in Netzwerk. The possibilities in Baal are too „permeated“Friedrich Cerha, Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 244 Transitions and material similarities contribute to the organic character of the music, which imparts a vine-like impression of intertwining plants. However, as Cerha explains in Schriften, three separate structural forms can be distinguished.

Interwoven fabrics, fields of closely layered notes for the natural sphere—and also for the inscrutable, the mythical sphere in which life is embedded. Expressive chords create colour where notes gather close together; conversely, in areas of colour, focal points emerge to push events in certain directions: directions that emerge from the shimmering, primal soup that holds so very many possibilities, effecting and demanding consequences. Polyrhythmic layering and juxtaposition, a sometimes formal, aleatoric repetition, characterizes the “social” spheres, which lie outside of Baal’s true interests. He speaks while society swirls and swarms around him, only beginning to sing once he is deeply immersed. Melody and harmony prevail in his individual expression, with expressive and formal intrinsic value growing from the narrative.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 244

Cerha’s description of Baal reveals two things about his understanding of nature. From a compositional point of view, the dense interweaving of notes is a reference to the music history of the twentieth century, a continuation of Cerha’s development. The creation of new textures with almost impenetrable, seemingly three-dimensional surfaces was one of his core foci towards the late 1950s, as heard in his innovative sound compositions Fasce, Mouvements and Spiegel. That this „archaic world“Writing about Fasce, Cerha describes its sound world as “archaic”. See Cerha, manuscript on Fasce WV 56, AdZ, 000T0056/5 in Baal serves to represent the the “natural” in Baal is also a reference to something else: the “natural” denotes only what is external, although the scenery certainly confirms it. Even more, it is meant symbolically to indicate isolation from the concrete and earthly, a bridge to the transcendental, to the unfathomable origin of existence, evoked musically by the shadowy and closely intertwined. The fact that such qualities increasingly shape the second act also reveals how Baal is turning away from the earthly. In the first act he struggles with his role in society, and there still seems to be a way out for him, but this impression soon evaporates. Baal decides against remaining in society—and thus against staying in this world at all.

The forest provides an alternative to the world of human culture, which is confirmed by a conversation between Baal and Ekart that almost prophetically anticipates the present-day climate crisis and more: “In 49 years, you can erase the word ‘forest’,” says Baal to his friend, decrying humanity’s hostility to nature. .

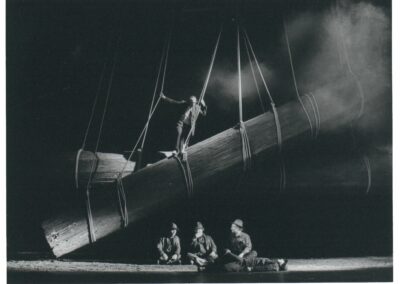

Produktion Neue Oper Wien (2011),

Sébastien Soulès (Baal), Michael Wagner (Ekart),

amadeus ensemble Wien, Ltg. Walter Kobéra,

Inzenierung: Leo Krischke

A poetic place, the forest does not stand for inner contemplation alone, in contrast to the harsh grindstone of human society. It also signals Baal’s departure from the physical world: his death. Accordingly, Baal integrates familiar metaphors, such as the romantic longing for death often symbolized by the forest. However, it also has connections to Expressionism, which provided a clear foundation for Brecht’s Baal, as can be seen in Arnold Schönberg’s monodrama Erwartung, completed in 1909. In this piece, a young woman, driven by dark forebodings, wanders through a forest at night in search of her lover. In the end, she finds only his corpse.

In Baal, the “forest” allies itself with morbid matters—indeed, it is allied with a death wish the main character sometimes commits himself to with frightening sensuality. There are several poems in the opera, which Brecht titled “songs”, that draw from images of forest and nature—forebodings that evoke Baal’s death and are sometimes reminiscent of mythical tales or nature fables:

Mainacht unter Bäumen (Akt 1, Bild 8)

Produktion Neue Oper Wien (2011),

Sébastien Soulès (Baal), Belinda Loukouta (Sophie),

amadeus ensemble Wien, Ltg. Walter Kobéra,

Inzenierung: Leo Krischke

Context

Nature

Nature is expressed in “Mainacht” in two ways: as an external, physical tangible object and as an internally experienced, symbolic state. In the setting of the scene, nature initially appears as a sheltering space: The leafy canopy of the forest protects Baal and Sophie from the rain, which is just letting up as the scene begins. Bedded down on dry roots, Baal and Sophie are isolated from the world around them. This lovers’ lair is reminiscent of Wagner’s “Garden with Tall Trees” in Tristan and Isolde, an almost metaphysical locus amoenus, detached from time and place.

At the same time, the wilderness of the location triggers morbid fantasies in Baal. The act of love tears one’s clothes from the body like “a whirlpool” and “buries one naked under the corpses of leaves”. In this way, the idyllic May night is transformed into an imaginary love grave—a union of death and passion.

Music

Avoiding a superficial sketch by employing deep tones, Cerha illustrates the poetically exaggerated natural scenery of the “Mainacht”. A solo horn takes one “as if from afar” from the tumult of the Corpus Christi procession to the tranquillity of togetherness, primarily accompanied by high string sounds. Bright, subtle orchestral colours create a moonlit aura of sound. The underlying string sounds—similar to the way they are used in Monumentum – correspond to the branching treetops, catching shorter splinters of sound. Irregular repetitions of the same notes join with other instruments to form a tonal image of dripping leaves, shaped by harps, plucked fiddles, marimba, and temple blocks with a wooden cracking sound, with antique cymbals providing flashes of colour.

Irrespective of the idyll, the music also follows the text in addressing the contrast between this world and detachment—particularly clear after Baal’s exclamation of “Ich liebe dich”, which echoes in fairy-tale-like violin chords that slow almost to a standstill. Sophie’s memories of her mother follow, gloomy thoughts conveyed by dark and shadowy wind instruments. But the high string sounds soon resume the lead, offering a bright ending to accompany Sophie’s words: “It’s good to lie here like trapped prey, the sky above you and you’re never again alone.”

Lied vom Mann im Wald (Akt 2, Bild 3)

Produktion Neue Oper Wien (2011),

Sébastien Soulès (Baal), Michael Wagner (Ekart), Elisabeth Lang (Maja), Oliver Ringelhahn (Gougou), Michael J. Schwendinger (Bettler), Dieter Kschwendt-Michel (Bolleboll),

amadeus ensemble Wien, Ltg. Walter Kobéra,

Inzenierung: Leo Krischke

Context

The trigger for the beggar’s song is Baal’s exclamation that “I am healthy”, a statement the beggar questions. The man he sings about also thought “he was healthy” until he underwent a confrontation with his self in nature, an experience that made him existentially doubt his perception of the world. In a typically Brechtian way, the emotionally charged story ends with a dry punch line, followed shortly by the “Aria of Nothing”, a nihilistic nod to the homeless Gougou.

nature

The “Song of the Man in the Woods” can be understood as a parable of human existence. It juxtaposes the human ability to freely move with the gnarled immobility of trees. The man speaking to the tree in the song does not seem happy with his freedom. He envies the tree for its stability, its groundedness, its deep-reaching roots, and the “great calm above its silent treetops”, a subtle nod to Goethe’s Above the Mountaintops.

In the opera, this parable serves a special dramaturgical function. It is not isolated in itself, but refers to the finale—to Baal’s lonely death in the forest. The dark tune is also linked to a later song sung by Baal, which bears the prophetic title “Death in the Forest” and is likewise an anticipation of his fate. Here, the images of a beggar are intensified: “And a man died in the never-ending forest, with darkness storming over him. Died like an animal caught in the tangle of roots. Stared up at the treetops where, high above the forest, storms had been rushing for days.” Both songs can be seen as prophecies that encode the cosmos of nature with (later legitimized) forebodings of death.

Music

The beggar’s song is closely interwoven with the conversation in the tavern. Over and over, comments, remarks, and questions from the guests interrupt him and the song, leaving the various idioms of the song juxtaposed but never connected.

Taken out of context, the song, sung by a bass, is an expressive performance with ominous undertones. Dark string cantilenas underpin the vocals, reinforcing its sinister character. The broad melodic arcs of the orchestra and vocals contribute to the overall sense of melancholy and song’s broad expressive character. Equally narrative and expressive, the beggar’s melodic gesture is based on spoken language. As a result, it is easy to follow the lyrics, something also facilitated by the slow tempo. The atmosphere of the song arises from four basic elements. The first is that of the fairy-tale; the very first line begins with “Once upon a time”. The second uses a tone marked by existential angst, the words and music reinforcing each other. For example, when the man throws himself on the ground, clutching the roots of the tree in tears, the events in the orchestra likewise escalate. But there are also reserved, tender moments that form a third building block; this is clearest when the beggar speaks of peace in the treetops. An empty but far-spanning fifth of E and B forms a soft background for the strings, upon which the singer and two horns linger. On the two syllables of the word “Ruhe”, the latter ensure that the fifth becomes a minor, then a major triad, which then immediately disappears.

Another design element comes into play when the beggar sings about the wind blowing through the treetops. The tree begins to tremble, reflected in the wildly overlapping glissandi of the strings. Brittle timbres, bolstered by the sul ponticello of the strings, imbue the sequence with surprising sensuality. Such “naturalisms” create an a nearly romantic interface between internal experience and external event that is almost characteristic for Baal.

Baals Tod / Frühe im Wald (Akt 2, Bild 12/13)

Produktion Neue Oper Wien (2011),

Sébastien Soulès (Baal), Oliver Ringelhahn (1. Mann), Daniel Serafin (2. Mann),

amadeus ensemble Wien, Ltg. Walter Kobéra,

Inzenierung: Leo Krischke

Context

The second act hints several times at Baal’s death, preparing us dramaturgically. In the end, this keeps the death scene from coming as a surprise. After Baal stabs his friend Ekart in an act of rage, he flees to the dance hall, where he is chased out after trying to force a girl to dance. Baal now seems unable to find a home. He eventually ends up in a hut, playing cards with four lumberjacks, who have nothing but scorn for the weakened Baal. They view him as scum, ridiculing and laughing at him, despite knowing he is nearly face to face with death. Instead of helping him in his final hour, they exit the hut, leaving Baal in solitude. With his little remaining strength, he drags himself out of the cabin to die, free and alone in the forest.

Nature

Until his very last breath, Baal is drawn to nature, to the trees. Even his last words—”trunks, wind, foliage, … stars …”—reveal how strongly his perception is focussed on that which is fundamental. And while he dies abandoned and alone in the wilderness, it need not be considered a bad death: Baal’s enduring longing to become one with nature is finally fulfilled. It also symbolizes the final stage of separation from the world, from culture, and from societal constraints. Baal finds his last resting place “in the lowest […] branches of the tree”—just as he once sang in his song “Death in the Forest”.

Music

Death and becoming one with nature thus converge in the final scene. The mythical power of the forest is invoked once again in the powerful aftermath of Baal’s final words. It is part of a musical texture that, according to Cerha, embodies nature—“interweavings” and “fields of dense tones”—a fabric that develops organically from Baal’s last words. A sense of suction is created that threatens to swallow Baal’s fragmentary exclamations whole. The bursts of energy then increase to the point of excess: Two large drums, three timpani, and shortly afterwards a tam-tam begin to play softly over Baal’s last words—a symbolic reference to the mighty roar of the conclusion. A dense urgency is particularly evident in the string section, which gradually builds up an immense cluster over almost six octaves. The stringent progression from low to high is reminiscent of Cerha’s early works, in particular the 55-part string piece Spiegel II. Sharp, repeated accents on the notes act as gigantic bursts of power that continuously multiply. The mighty string-laden chord fluctuates even as it emerges: While the voices sustain some of the tones, others change. Once again, the compositional viewpoint turns towards the 1960s as the differentiated movements within the sound complex somehow retain great energy. The development of power within the confined space is founded on an extreme layering of sound material. Particularly striking are the variations of an ascending, motivic figure above the string chord, increasingly unravelling. This is created through instruments of a bright timbre, in the high winds, as well as in the glockenspiel and vibraphone—as if Cerha were trying to choreograph Baal’s stargazing, the last perception of a dying man who finds himself otherwise in utter darkness.

With Baal’s death, the intertwining of the individual voices gradually dissolves. In the morendo, the roaring percussion is the first to fade away, and finally the wind instruments also fall silent. In the end, only the strings remain, levelling off on a final axis, on an E. This process of shrinking the tonal space is again reminiscent of Cerha’s soundscape compositions of the 1960s: Both the Spiegel cycle and Fasce end in a single note after a long period of reduction—a gesture that acts as a farewell to the previous complexity, and reflects Baal’s turning towards the elemental.