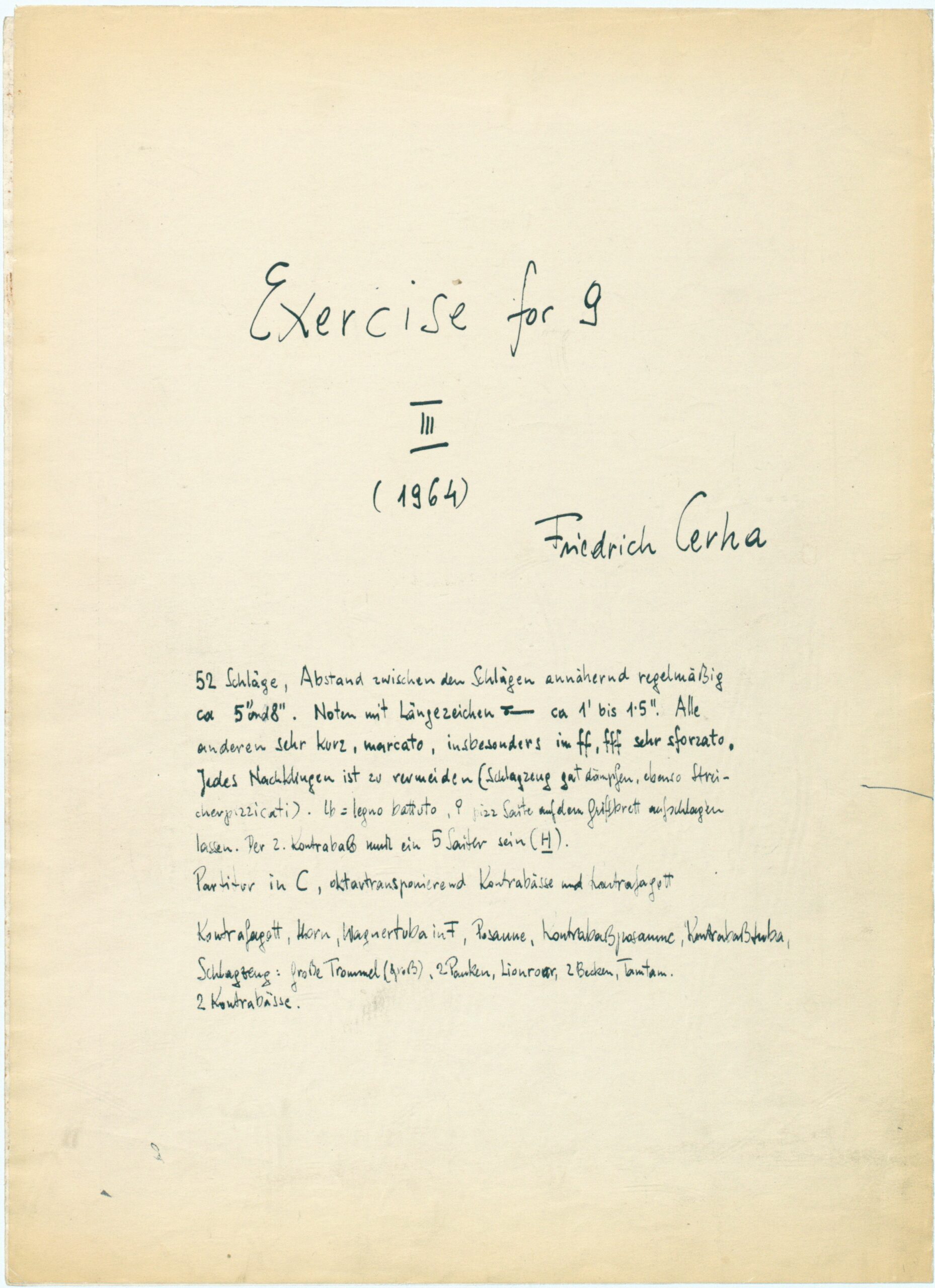

Exercises

Music as Growth

Baal

Monumentum

Sawtoothed spurge leaves

Euphorbia serrata, also known as the serrated spurge, is native to Europe and North Africa. Today considered a weed, it grows all over the world—so adaptable that it has now become a typical species of the genus.

Source: Alvesgaspar / Wikimedia

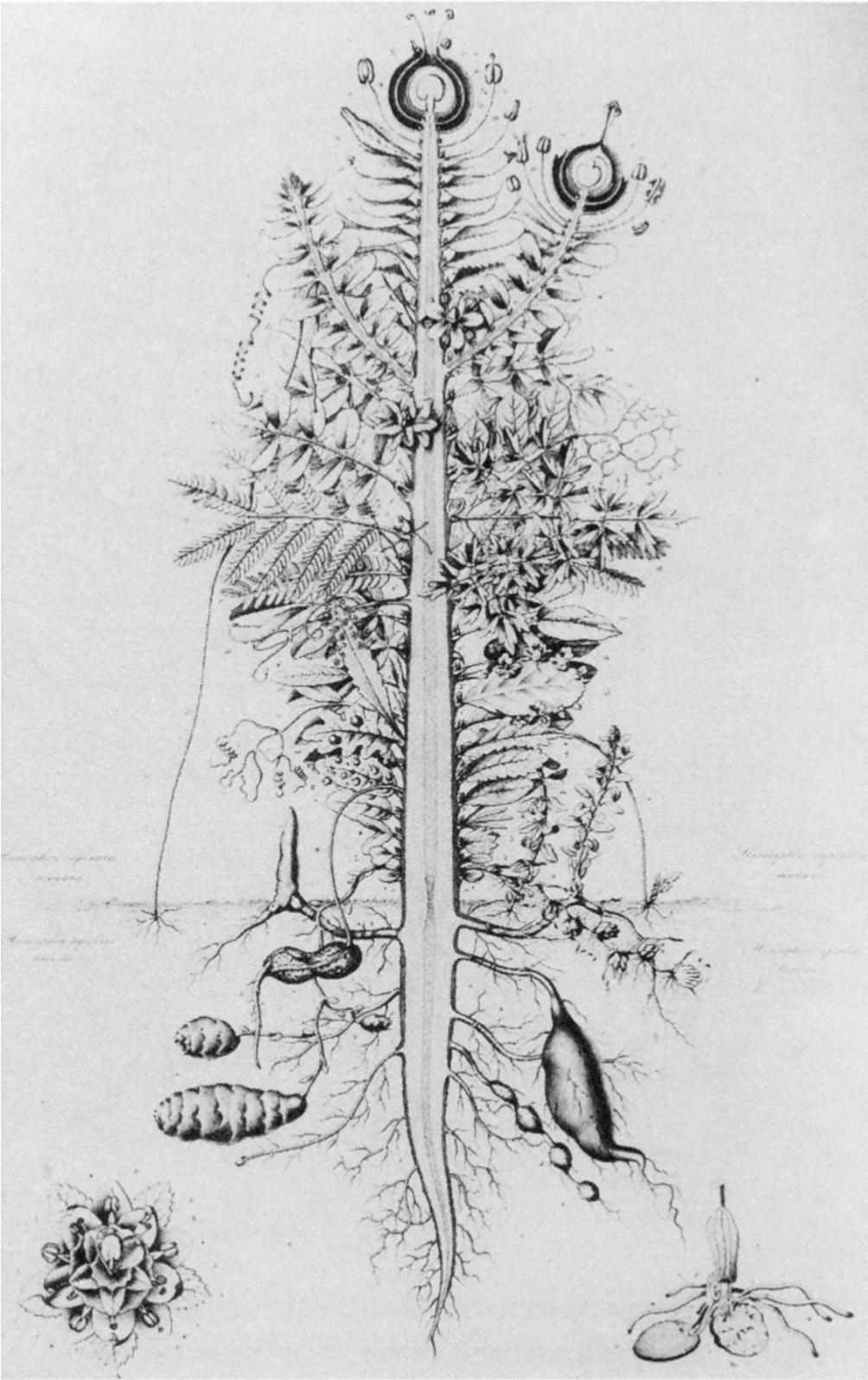

It’s hard to believe: One genus of plants and so many different shapes—more than 2,000 species are distributed across the world, from lowland deserts to high mountains.

All of these plants—each of the various species growing around the globe—bear the scientific name of Euphorbia. Their superiority comes from an extreme adaptability to different living conditions, a phenomenon which so fascinated Cerha that he turned it into a musical concept—one that allows Exercises to thrive.

Außenansicht

When Cerha is working on a piece, it often follows the swing of a pendulum: After intensively saturating himself in an area of interest, the composer usually then seeks out contrast, an approach towards change that is underpinned by his great curiosity and unwillingness to commit to an ideological attitude. The early 1960s were a particularly exciting period that saw great shifts both in society and in the compositions of Cerha, who was in his mid-thirties at the time. In 1961, the astronomical cycle Spiegel was completed. His largest project to date, the work included a symphony orchestra of immense size, hyperdense masses of sound, and a utopian and literally unheard-of kind of music. Spiegel fulfils a vision of radical nuance within a musical fabric, stylistically pure in the very best sense. This “ever finer designing of a small space”Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 71 could not, however, entirely satisfy Cerha: His internal “unrest could not be calmed”, repeatedly reigniting itself. Even while Cerha was still hatching Spiegel , bhe began a new project the same year, dreaming of “music without bounds“Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 74, that is “neither rounded out, satisfied, nor filled with perfection”. The years to come were occupied by the pursuit of this musical mental image. In 1963, Cerha noted that he was “looking for a title for the work as a whole” and landed on Exercises: „”I like it because it doesn’t call up any associations—and because it highlights aspects of a workshop.“Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 75 Cerha kept the title once the composition was completed, following his self-designed programme. “Exercises are about training, the result of which is experience”, he summed up when finalising the work in late 1967.

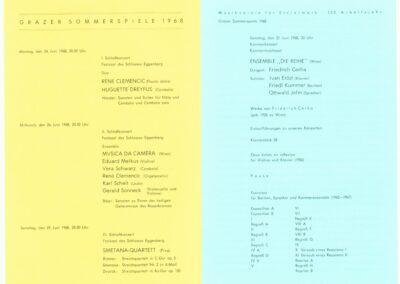

World premiere of Exercises: Cerha and “die reihe”, Zentralsparkasse Vienna, 26 March 1968

Brücke

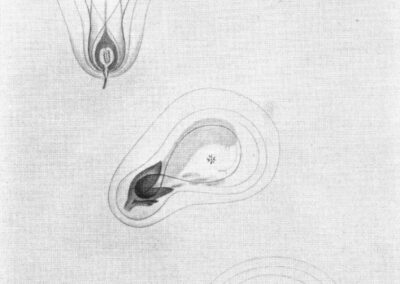

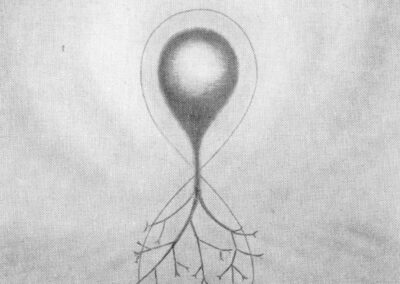

Cerha’s affinity for natural phenomena, especially those of the plant world, manifests itself in the Exercises for the first time with concrete references to things he observed. “Even his early works”, says musicologist and friend Lothar Knessl, “showed how one thing grows out of the other, imaginatively integrating variations in the broadest sense, mutations, and laws of nature.”The concept of integral composing—the development of the music from a single nucleus—plays an important role for Arnold Schönberg, for example. He uses this guiding principle, calling it “developing variation”, in his 12-tone works in particular. The idea of varying a basic idea and then using the resulting modifications as a starting point for new variations implies constant change while retaining the connecting elements. It is based on a harmonious worldview that was quite popular in Vienna in the early twentieth century. Anton Webern, with whom Cerha interacted extensively in his younger days, also subscribed to the concept.

Es ist immer Dasselbe, und nur die Erscheinungsformen sind immer andere. – Das hat etwas Nahverwandtes mit der Auffassung Gothes von den Gesetzmäßigkeiten und dem Sinn, der in allem Naturgeschehen liegt und sich darin aufspüren lässt. In der „Metamorphose der Pflanze“ findet sich der Gedanke ganz klar, dass alles ganz ähnlich sein muss wie in der Natur, weil wir auch hier die Natur dies in der besonderen Form des Menschen aussprechen sehen. So meint es Goethe.

Und was verwirklicht sich in dieser Anschauung? Dass alles dasselbe ist: Wurzel, Stengel, Blüte. Und auch bei den Wirbeln des menschlichen Körpers ist es nach der Anschauung Goethes ähnlich. Der Mensch hat eine Reihe von Rückenwirbeln, und alle sind verschieden voneinander und doch wieder gleich. Urwirbel – Urpflanze. – Und es ist Goethes Idee, dass man da Pflanzen erfinden könnte bis in die Unendlichkeit. – Und das ist auch der Sinn unseres Kompositionsstils.

Anton Webern

Der Weg zur neuen Musik, hg. v. Willi Reich, Wien 1960, S. 42 f.

It is imperative to see Cerha’s interest in botany in the context of the Viennese School, with independent and original facets appearing throughout his work.

The Botanical Garden of the University of Vienna was an important place for Cerha during this era. He spent hours there, refreshing himself and studying its great variety of plants. It was there that he was able to study the diverse types of euphorbias up close; it comes as no surprise that the documentary Zu Gast bei Friedrich Cerha was partly filmed on site. In one film sequence, Cerha tells of the musical potential of his discovery:

Innenansicht

Succulents at the entrance of the University of Vienna Botanical Garden

Bildquelle: Gugurell

I have decided to emphasise references to traditional material, which are sometimes veiled but not always avoided, and have included them in my work in various forms and to various degrees. What emerged in this process was an increasing concentration on the concept of “composition” in the root sense of the word, sought out in various materials.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 71

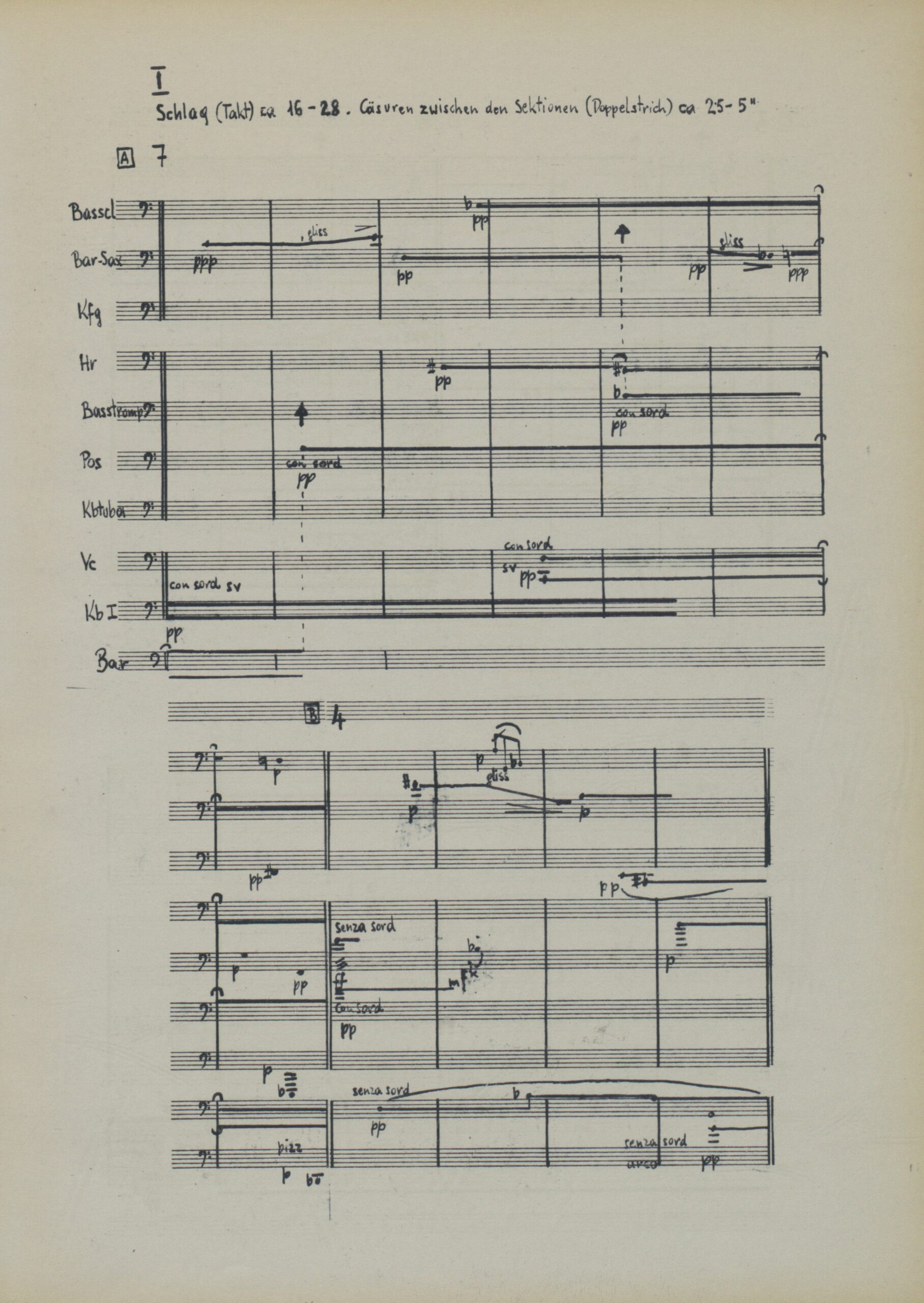

The combination of different things—the original meaning of the word composition—occurs in Exercises through the establishment of two parallel levels. Cerha calls one level the “main movements”—they were first composed and then arranged in a certain sequence. In these main movements, the musical form unfurls along an imagined evolutionary timeline. This development clearly follows the idea of metamorphosis as familiar from botany—i.e., the transformation of plant organs into roots, shoots, and leaves due to different living conditions and environmental factors. Cerha creates an artificial environment in Exercises by including a second level that he calls “regression”. These pieces can be understood as a renewed transformation, albeit of an entirely different kind. The allusion of the chosen name—“Regresse”—to regression is not pure coincidence, but is a reference to a musical concept. Regressions „fall back from higher organisational levels to more primitive basic material, and are often even more regressive in terms of style.“Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 233 The sequencing of these two levels infuses Exercises with an exciting interplay. Ultimately, the main focus of the composition is the great diversity of the musical sections, which causes „clichés disguised as styles to fall away”>Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 82 Cerha’s distance from the mainstream collage composition of the time becomes clear upon examining the tension between an organic and an artificial understanding of music, a tension which drove Cerha forward when working on Exercises :

At the time of their writing, the regression had more of a shock impact than the musical quotes and collages, which have the effect of turning everything into a game of aesthetics by disregarding “style” to varying degrees and thus doing damage to “taste”. Unlike collage, which uses breaking away and distortion as essential parts of the experience, it was important to me to not only create breaks, but also to organically integrate what had been broken: Breaking away and communication occupied me in equal measure.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 233

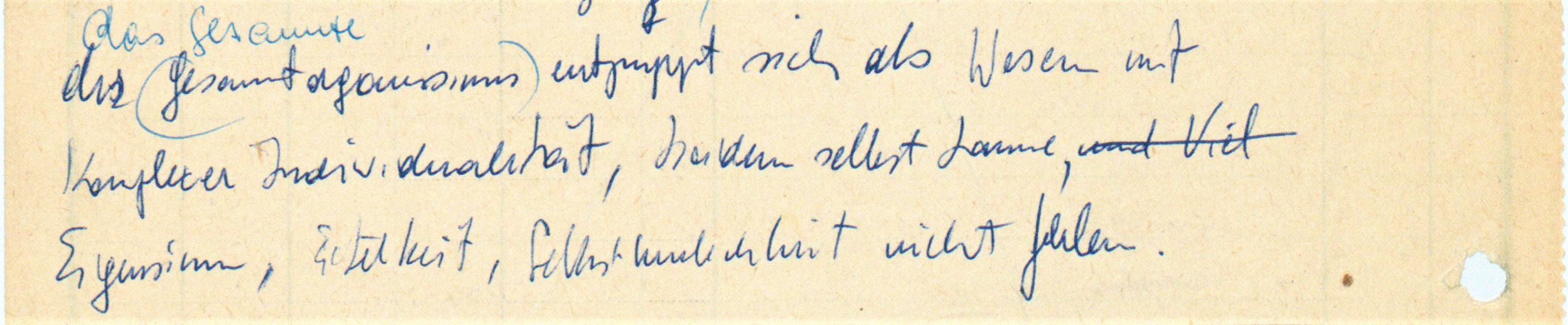

Looking at the polarities—synthesised cutting on the one hand and organic naturalism on the other—the structure of Exercises is not without contradiction. Cerha paints a fascinating image. As his final notes on the piece in late 1967 conclude:

“The organism has revealed itself to be a being with complex individuality, in which even moodiness, obstinacy, vanity, and self-importance are not lacking.”

Cerha, notes on Exercises, AdZ, 000T0061A/46

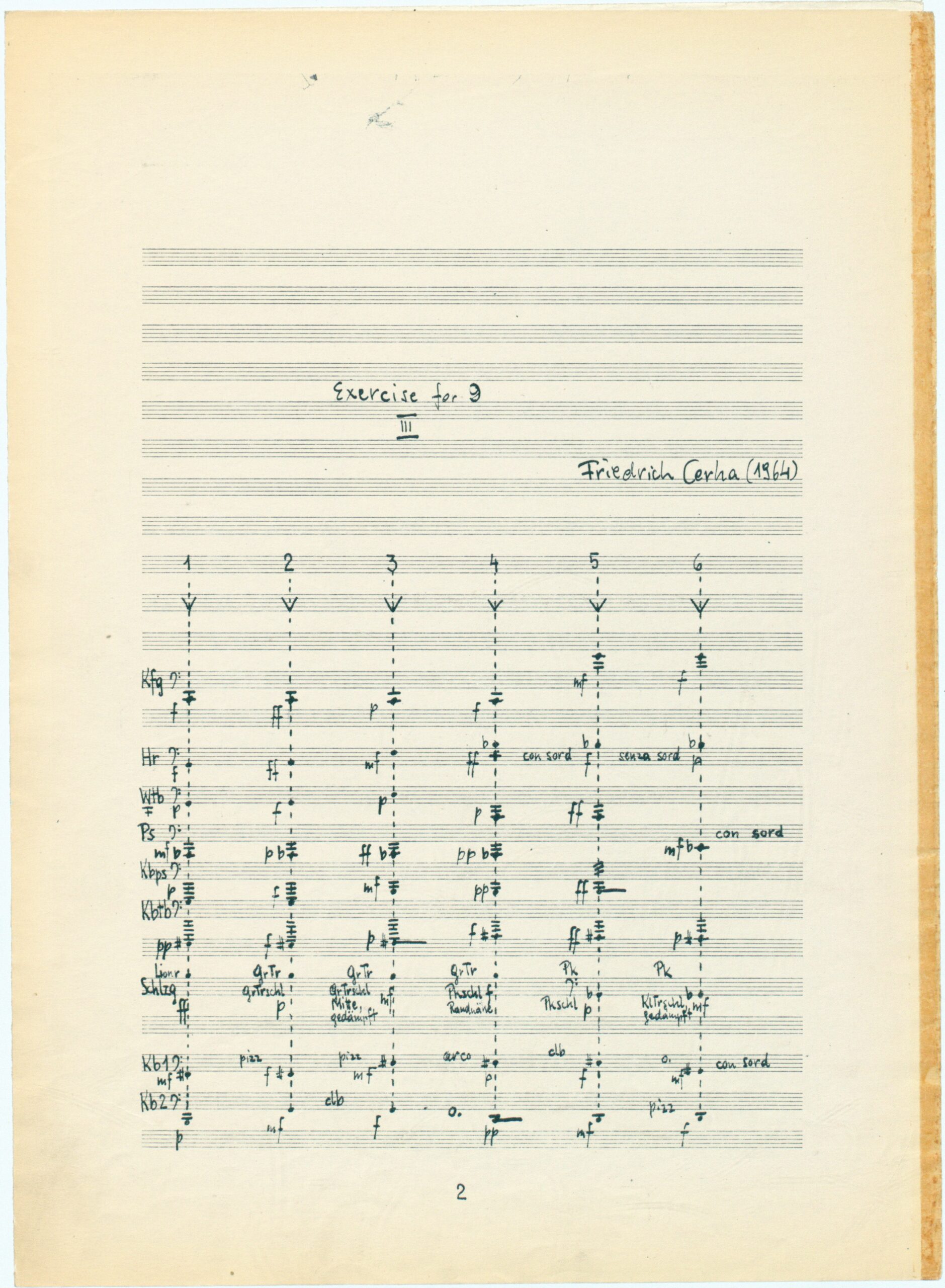

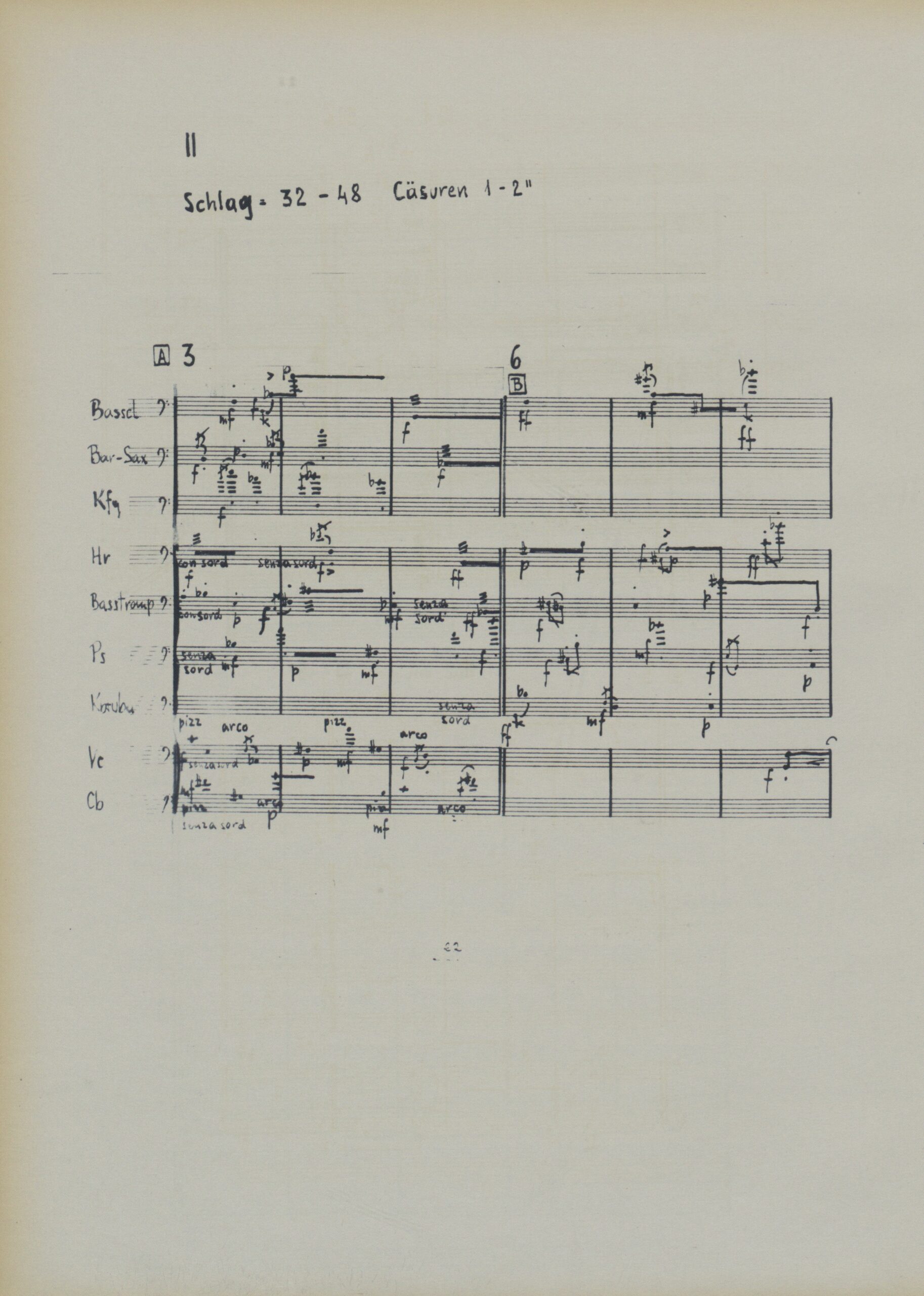

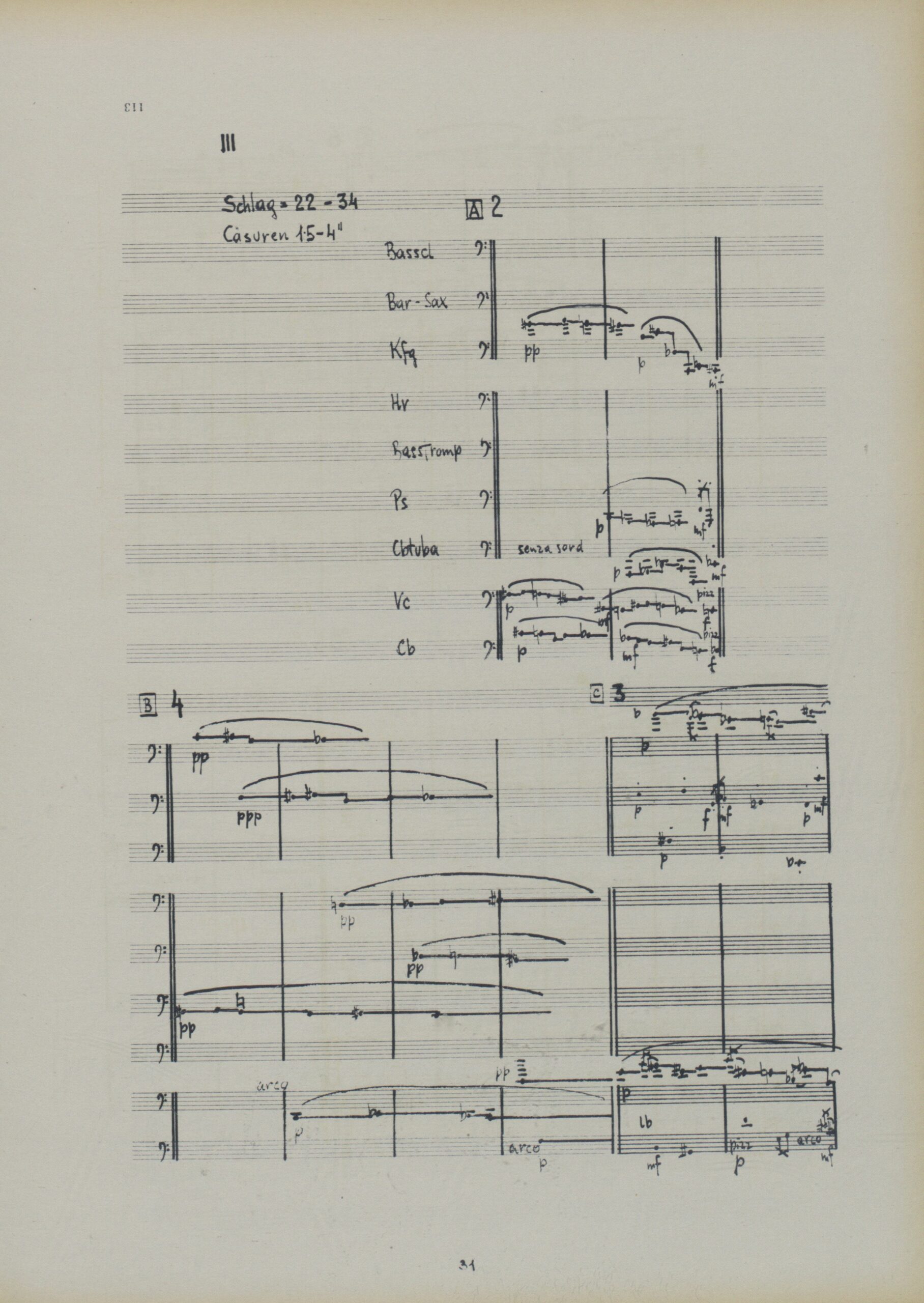

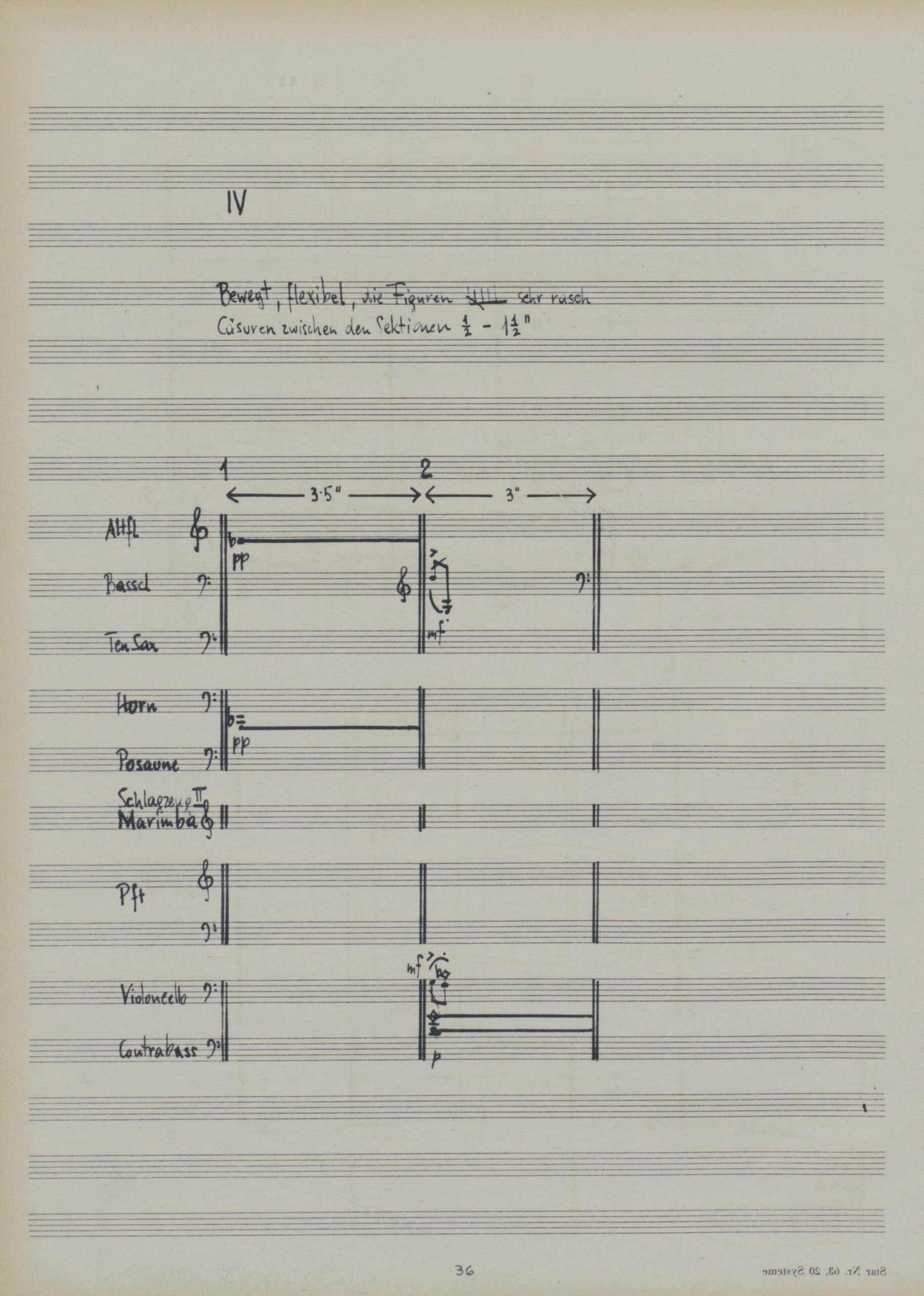

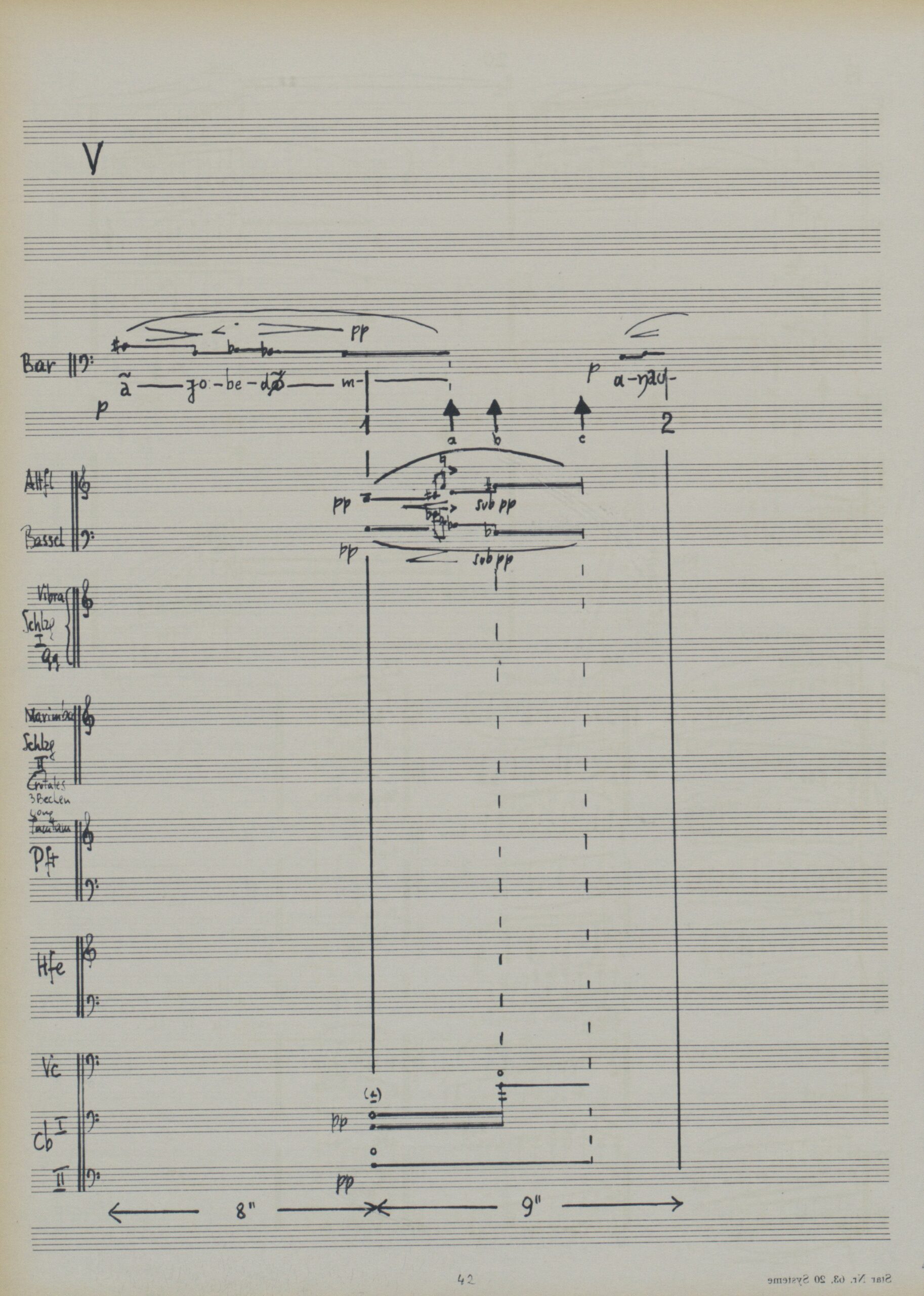

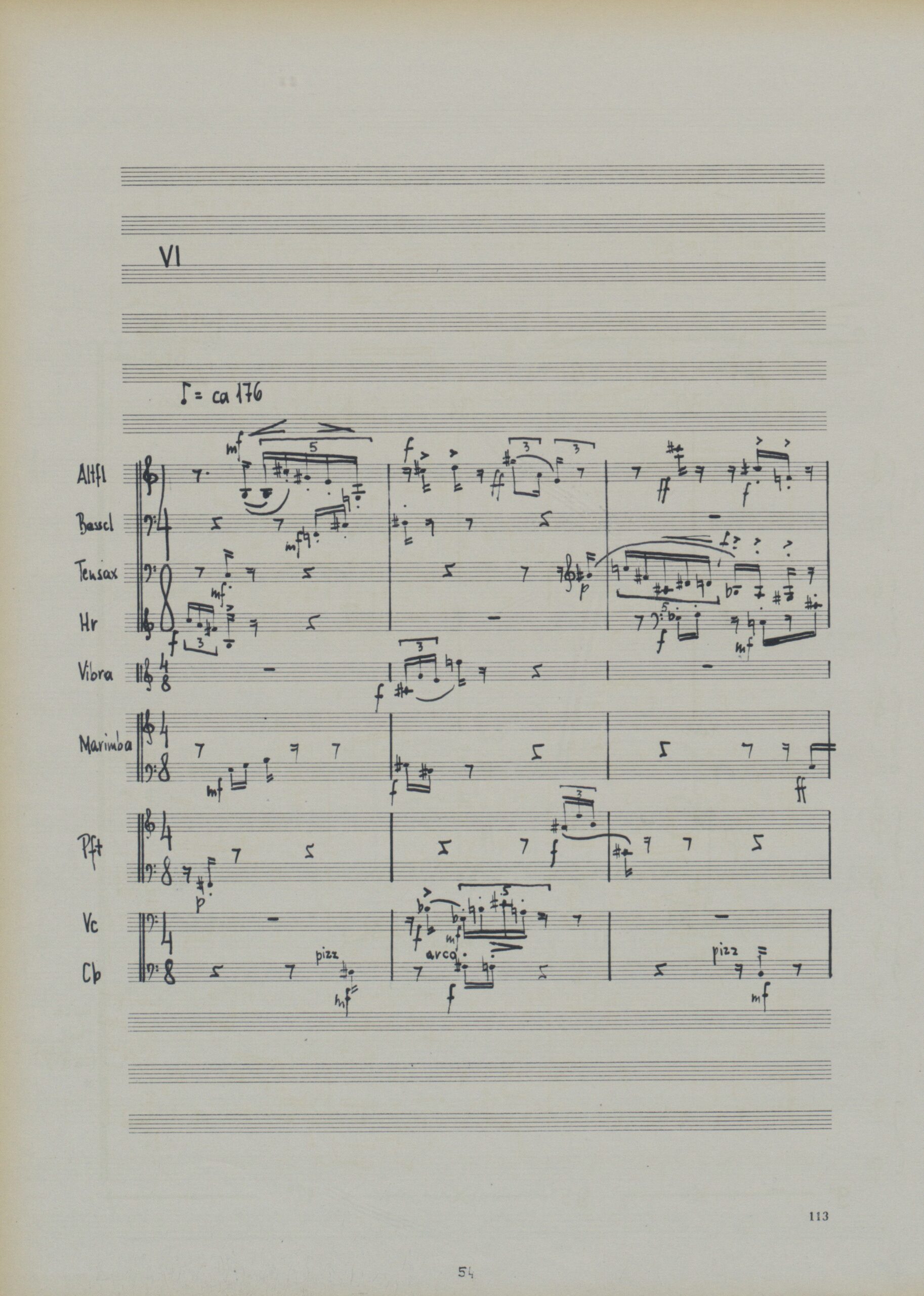

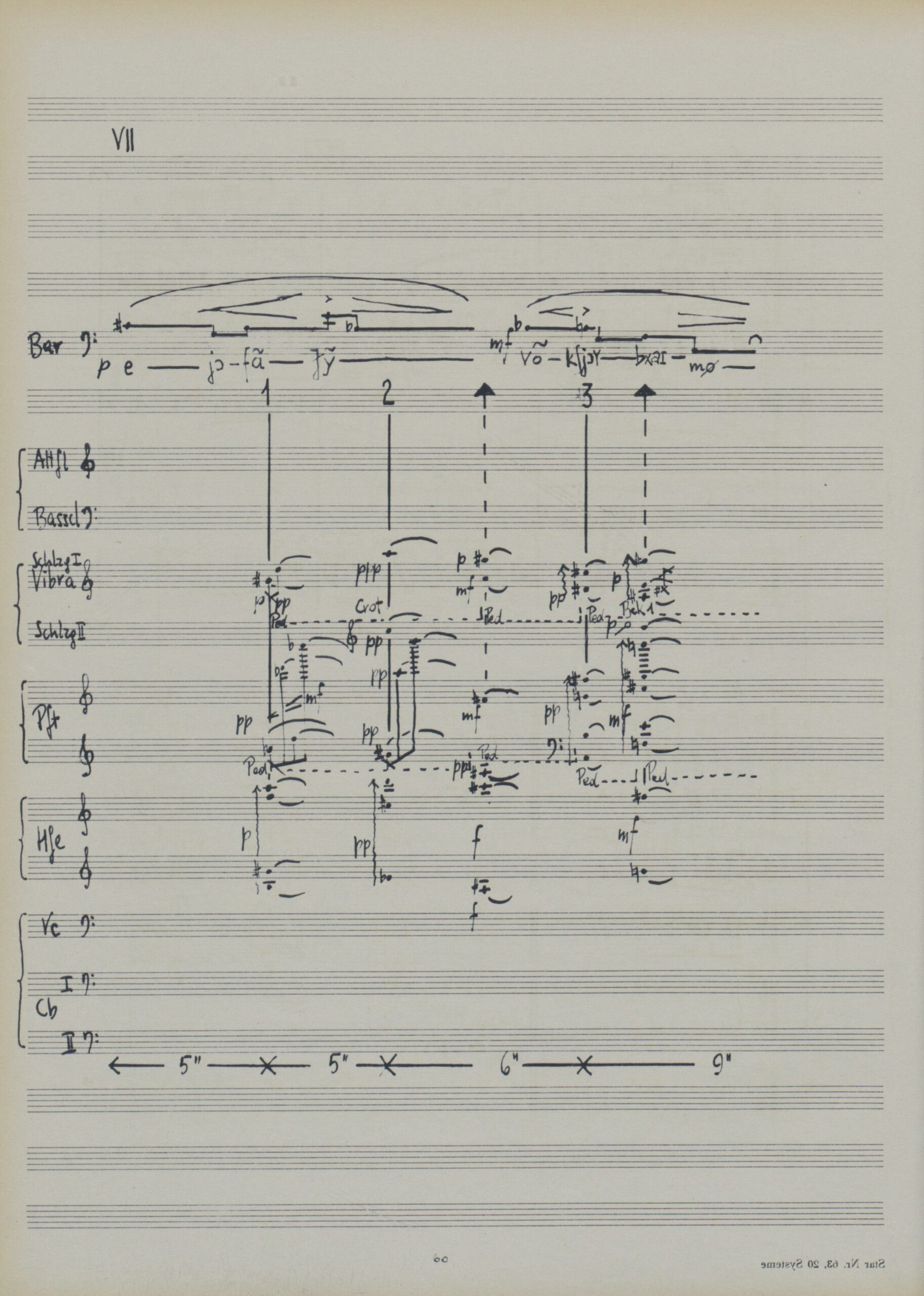

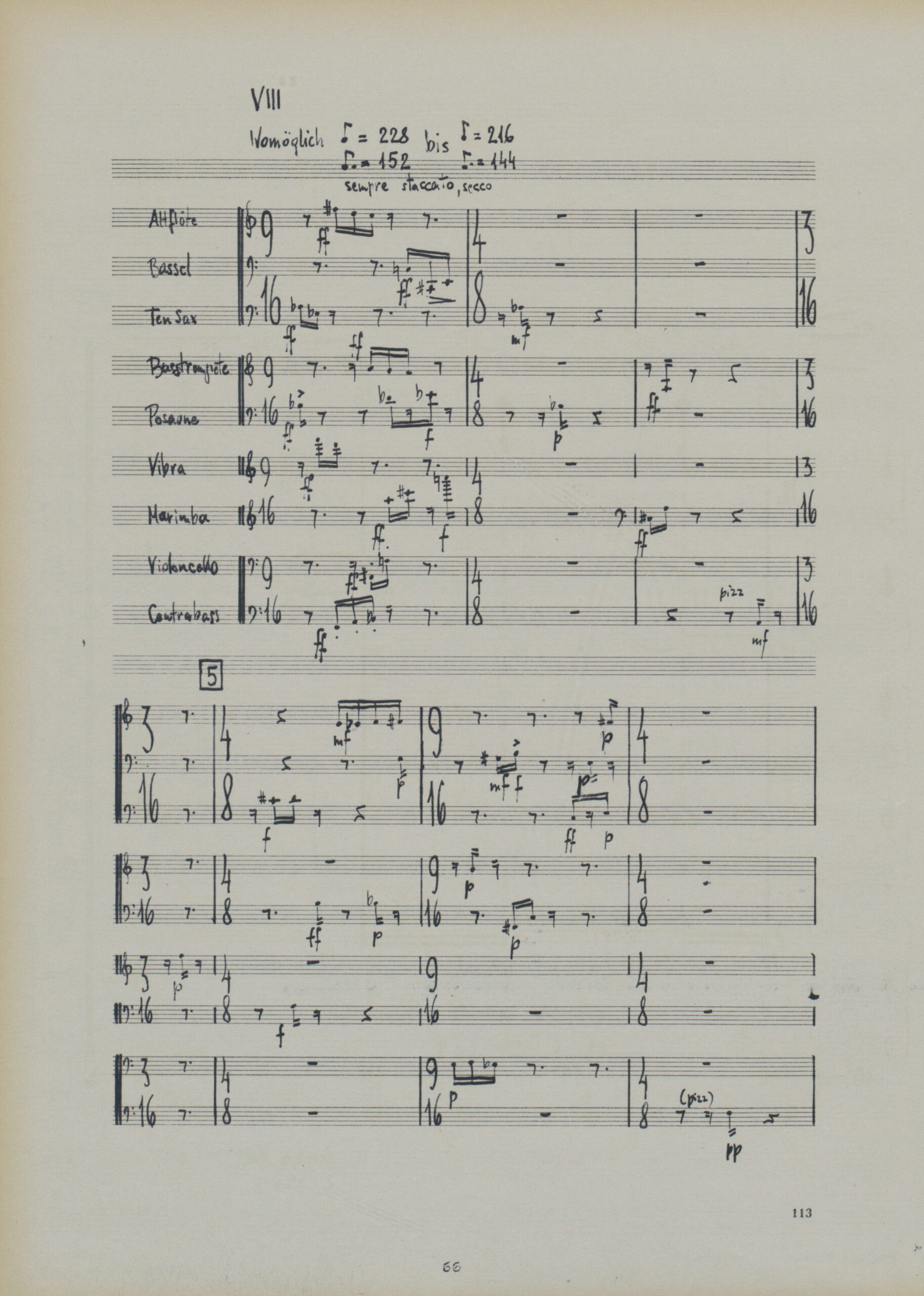

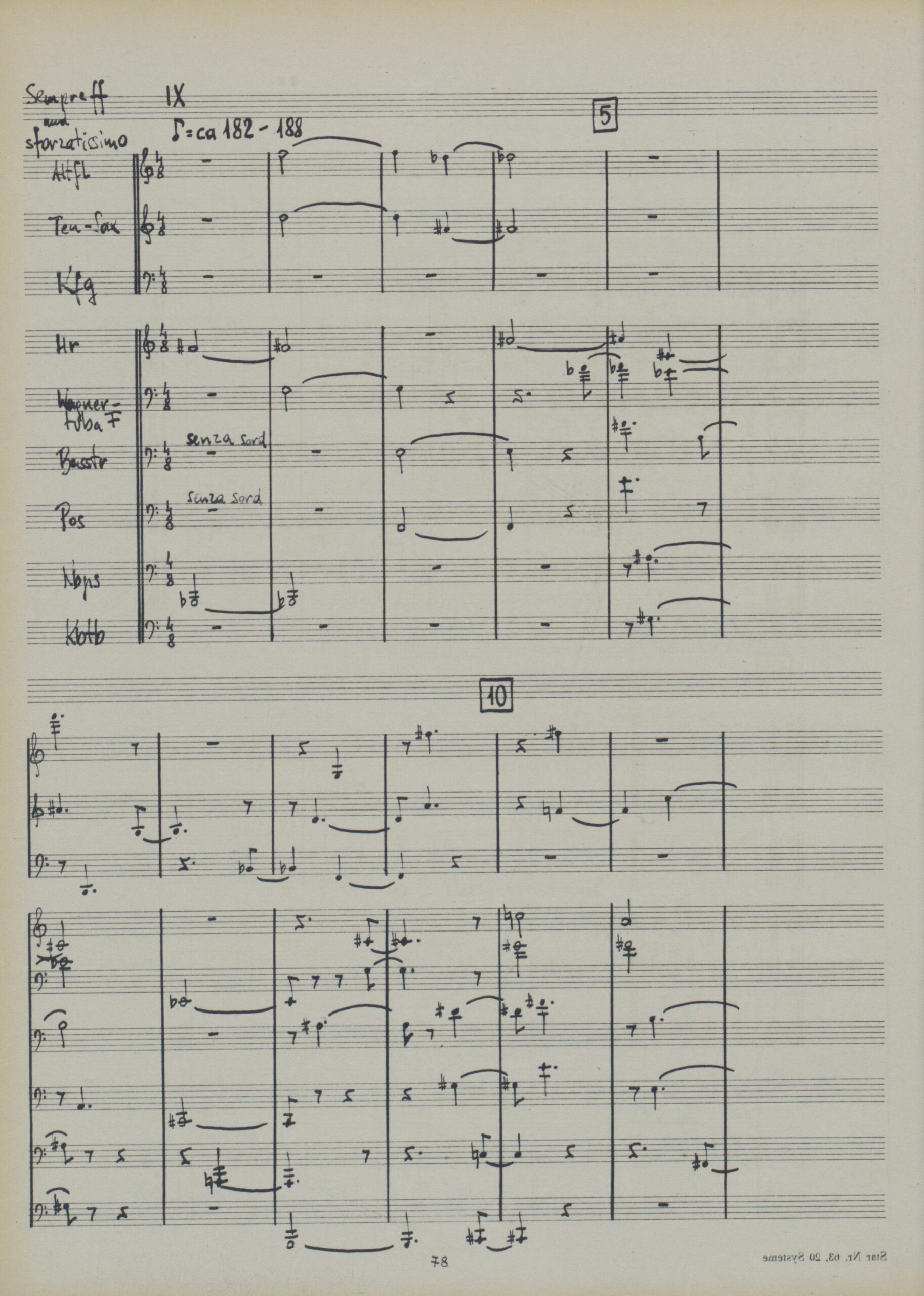

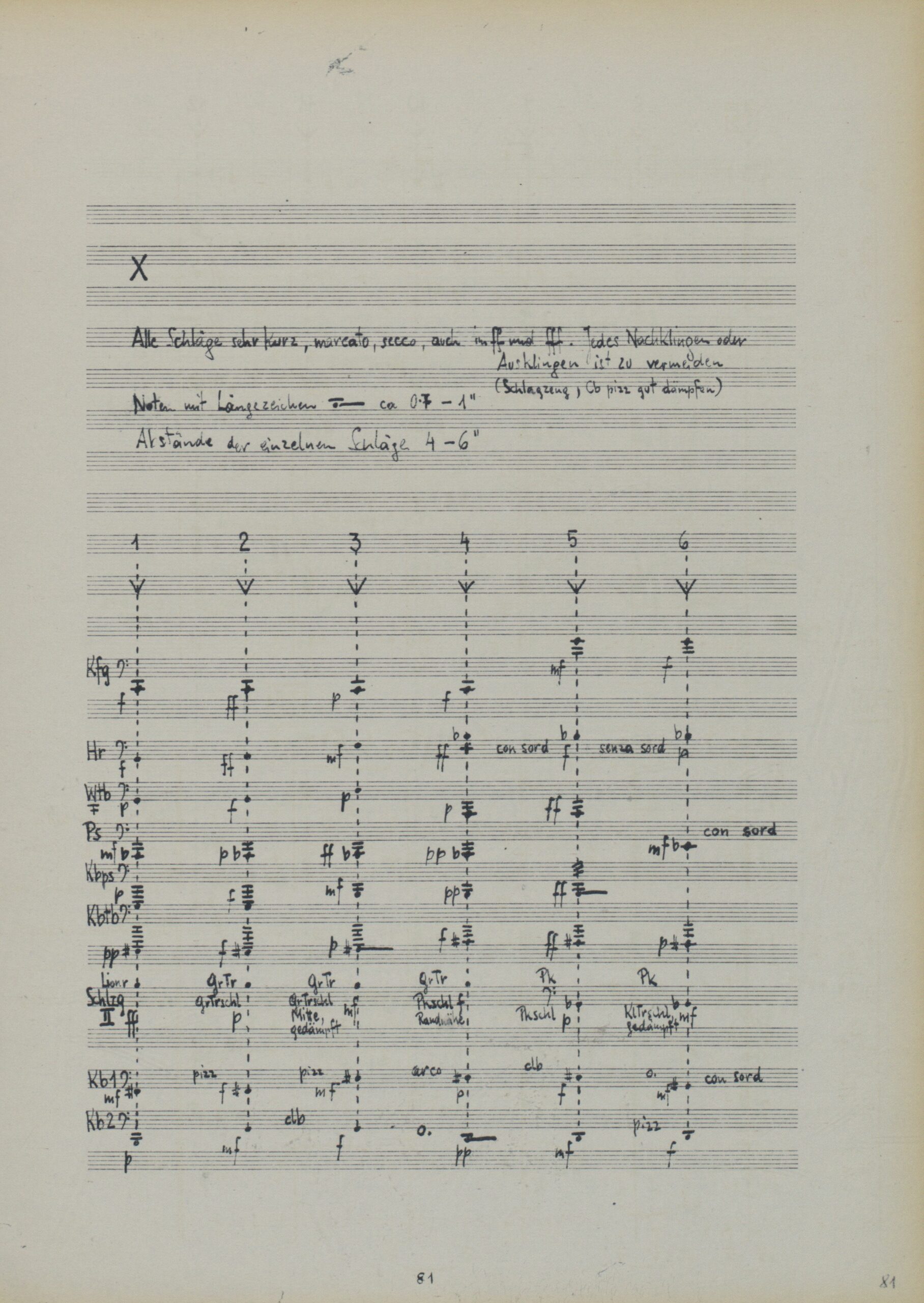

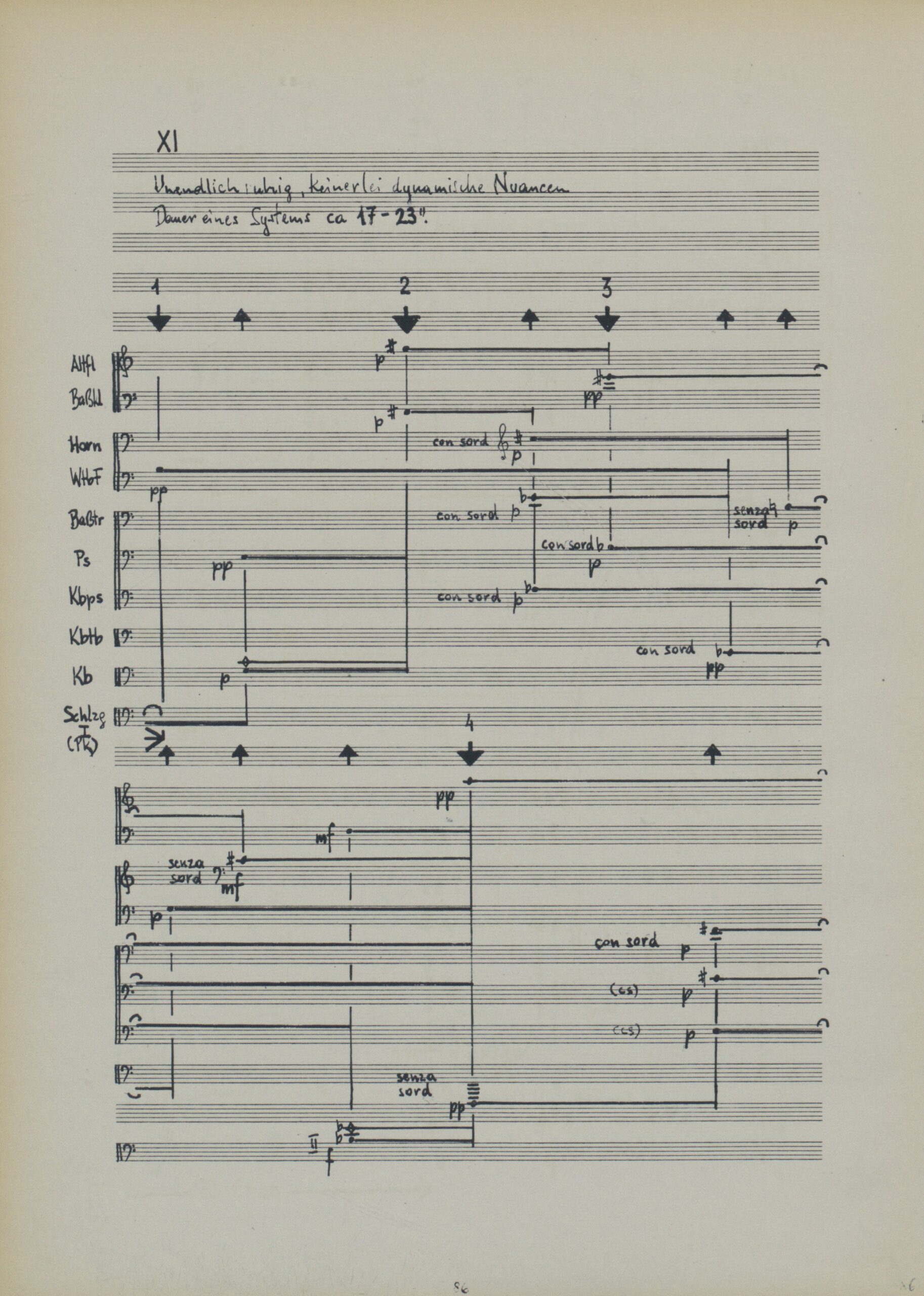

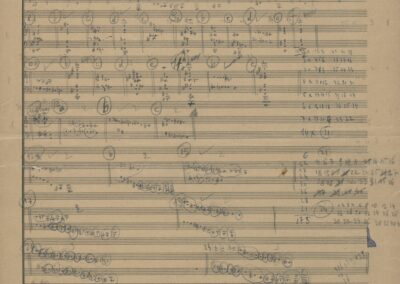

Exercises for nine, Ursatz, first page of score, 1964,

AdZ, 00000061/3

Exercises for nine (Ausschnitt)

“die reihe” ensemble, conducted by Friedrich Cerha, Museum of the 20th Century Vienna, 1963

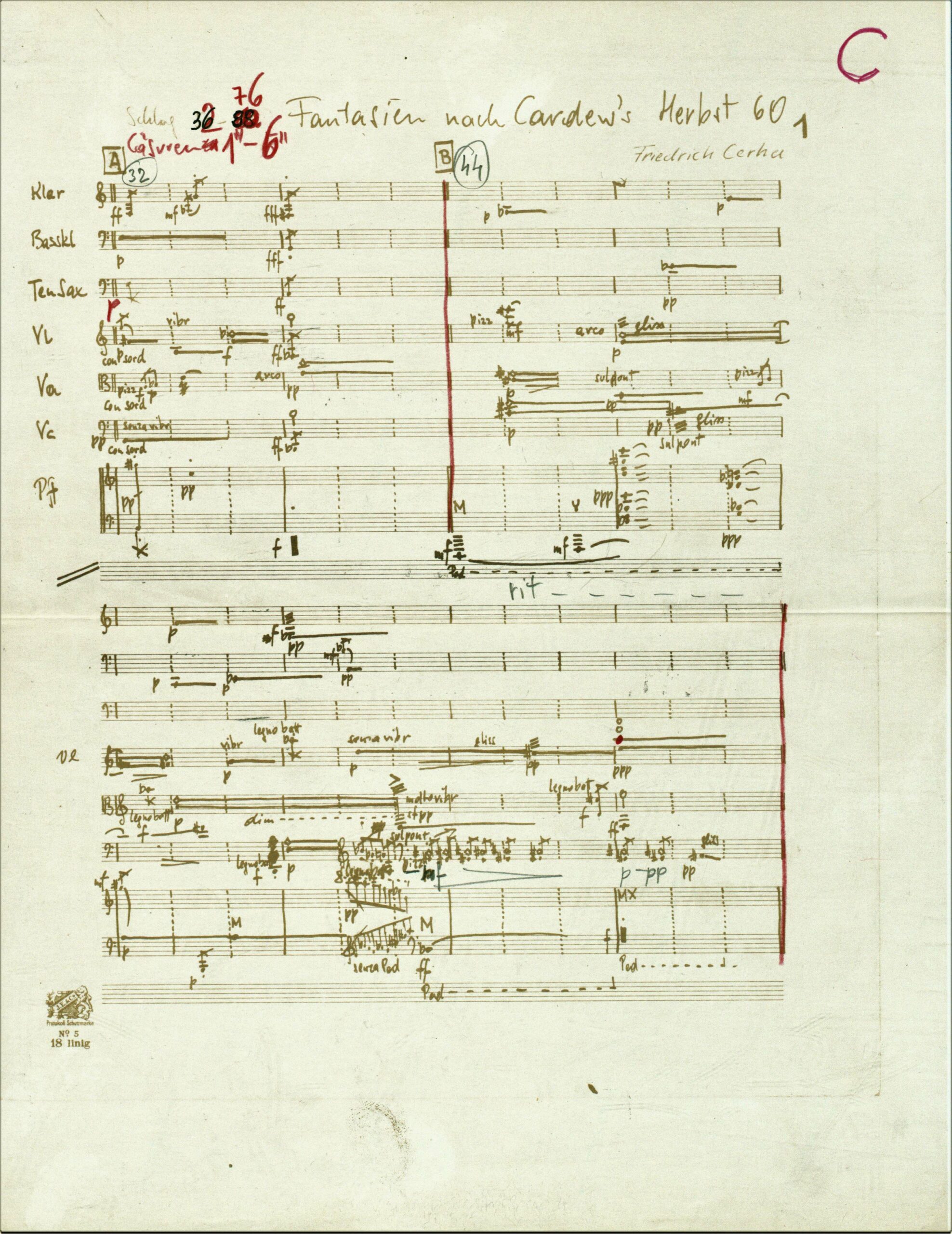

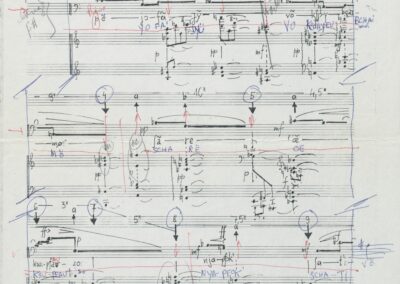

Fantasien nach Cardews ‚Herbst 60‘, first page of score, 1963,

AdZ, 00000060/2

Fantasien nach Cardew's 'Herbst 60' (Ausschnitt)

Ensemble für Neue Musik Siegen, conducted by Ute Debus, University of Siegen Music Hall, 2017

The movements are so solidly compressed that they seem like simultaneous strikes. As in nature, distortion does not occur with absolute uniformity: Now and then notes arrive too early, others linger too long. The pauses, which are always the same length and seem very long, are kept and the movement rolls relentlessly into the abyss of time. I later named it “Versuch eines Requiems I“.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 232

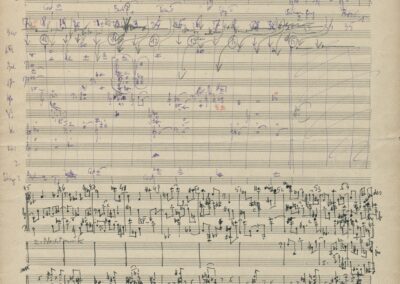

MThe creation of the second piece as a „distortion“Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 75 dof the first set makes a bed for the ongoing growth of Exercises as an evolving organism: The two movement are the germ cells for all that follows. That same year, Cerha performed the two movements under the name Exercises for nine (the title alludes, among other things, to the nine-instrument line-up).

Over the next four years, the first version of Exercises for nine was expanded into a multifaceted and complex work. By 1967, 11 main movements and seven regresses, each more or less symmetrically bracketed by two expositions and reprises, constituted the final version of Exercises. Cerha notes: „Those around mocked me, saying that no one would be able to stand a performance because the piece had grown so relentlessly.“Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 84

The way that the music ultimately expresses the ideal of botanical diversity can be seen through a comparison of the individual stations of Exercises. It is the main movements, which are unalloyed, self-contained units, that most clearly convey the principle of metamorphosis. The individual movements almost seem like an encyclopaedia of (musical) categories.

Ensemble „die reihe“, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha, Arthur Korn (Bariton), Produktion ORF Edition Zeitton 2001