Zweites Streichquartett

Am Fluss des Krokodils

Phantasiestück in C.’s Manier

Zehn Rubaijjat des Omar Chaijjam

Men’s Houses, Tambunum, Papua New Guinea

Men’s houses are an integral part of the Iatmul culture and often form the heart of a village. The façade of the “Crocodile Clan” building displays typical ornamentation: Wave patterns symbolising the tribe’s strong connection to the Sepik River. The head of a female spirit emerges from the centre.

Evidence of a bygone era?

A large skull suspension hook from Papua New Guinea is one of the most impressive objects in Cerha’s private collection of cultural artefacts from around the world.

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

For the Iatmul, a tribe of several villages along the Sepik River in Papua New Guinea, the keeping of skulls is not just a tradition, it is also an art form. The skulls of important ancestors are painted to match the face painting of the person during their lifetime, their eye sockets decorated with cowrie shells, and their heads adorned with real hair. The skulls are then hung on decorative boards or wooden figures with hooks. Cerha acquired his hook sculpture in around 1990, at a time when the composer’s interest in non-European music and culture was at its peak. The Iatmul culture had a strong impact on the works he created at that time, demonstrated with particular intensity in the second string quartet.

Außenansicht

It would not be surprising to learn that a composer who studied violin at a music academy and also specialises in both old and new music traditions wrote his first string quartets at an early age. For Cerha, however, this was not at all the case. His first true string quartet dates from 1989—meaning it was written when he was 63 years of age. In addition to this late debut, another point is worth noting: The first string quartet was almost immediately followed by a second, tying in seamlessly to his catalogue raisonné. A third quartet then joined the first two in 1991, after a break of barely a year. This marked productivity in a traditional genre did not come about by coincidence. In the late 1980s, Cerha received two separate commissions. One contract was awarded by the Salzburg Mozarteum Foundation on the 200th anniversary of the death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, a master of the genre. Almost simultaneously, a second request came from the international string quartet competition in Evian, France. Cerha not only accepted both commissions, but quickly combined them with his personal artistic “research goal”:

In my life as a violinist, I have played a great deal of chamber music and know the literature well. Two string quartets and a string trio written in my youth ended up in the trash while deep cleaning in the early 1960s. The two commissions for string quartets in 1989 and 1990 […] were a welcome connection with my open desire to be inspired in new linguistic and stylistic fields.

Friedrich Cerha

Cerha, essay on the 1. Streichquartett WV 104, AdZ, 000T0104/2

There is a strategy behind Cerha’s breakthrough into string quartets: The infiltration of the familiar world with the new and the foreign. Like a field researcher, the composer examines unfamiliar musical terrain, finding, in the quartet, the perfect tool. The approach has a storied tradition: Haydn and Beethoven also used the string quartet to venture into new musical territory. One reason for this is that the tonal homogeneity of the four stringed instruments favours experimentation by providing a narrow framework which virtually ensures clarity and transparency.

1. Streichquartett, handwritten score, title, 1989

2. Streichquartett, handwritten score, title, 1990

Brücke

In order to avoid the creation of any misunderstandings, however, I would like to expressly point out that this is, of course, neither […] about imitating the stimulating exoticism of non-European music, nor about appropriating the expressive values of other peoples. The end product is definitely music from our culture; a music, of course, honed by a creative imagination inspired by musical conditions and constellations that do not exist in our part of the world.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 257

Innenansicht

Tribe playing hourglass drums in Papua New Guinea for a ceremony

Source: Bea Amaya / Pixabay

And while these foreign influences are both introduced into the first two string quartets, the resulting formats differ greatly. The “Maqam” quartet is structured almost like a suite. Cerha considers Arabic music in 11 subsections; the cultural influences are, at times, barely noticeable, and at others much more palpable. The second quartet has no such divisions, unfolding instead “in a continuous arc”.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 261 Musical gestures float by like clouds, with no breaks or gaps. At the same time, a large arc enfolds the entire piece, containing the music—music that, as Lukas Haselböck describes, has an extraordinary power of communication:

This arc rises mysteriously and delicately with steadily mounting tension to achieve a furious climax, which ultimately subsides into an immobile, rigid chord, formed by a composer with the narrative skill to create an exciting interaction between elements, temporal sequence, and structure.

Lukas Haselböck

“Zum Erleben von Prozessen: Cerhas 2. Streichquartett und Phantasiestück in C.’s Manier”, in: Haselböck, (ed.): Friedrich Cerha. Analysen, Essays, Reflexionen, Freiburg et. al 2006, pp. 95–120, here p. 95

Papua New Guinean coat of arms with a bird of paradise holding an hourglass-shaped Kunda drum, a typical instrument for the Sepik

Station No. 1: The Realm of Overtones

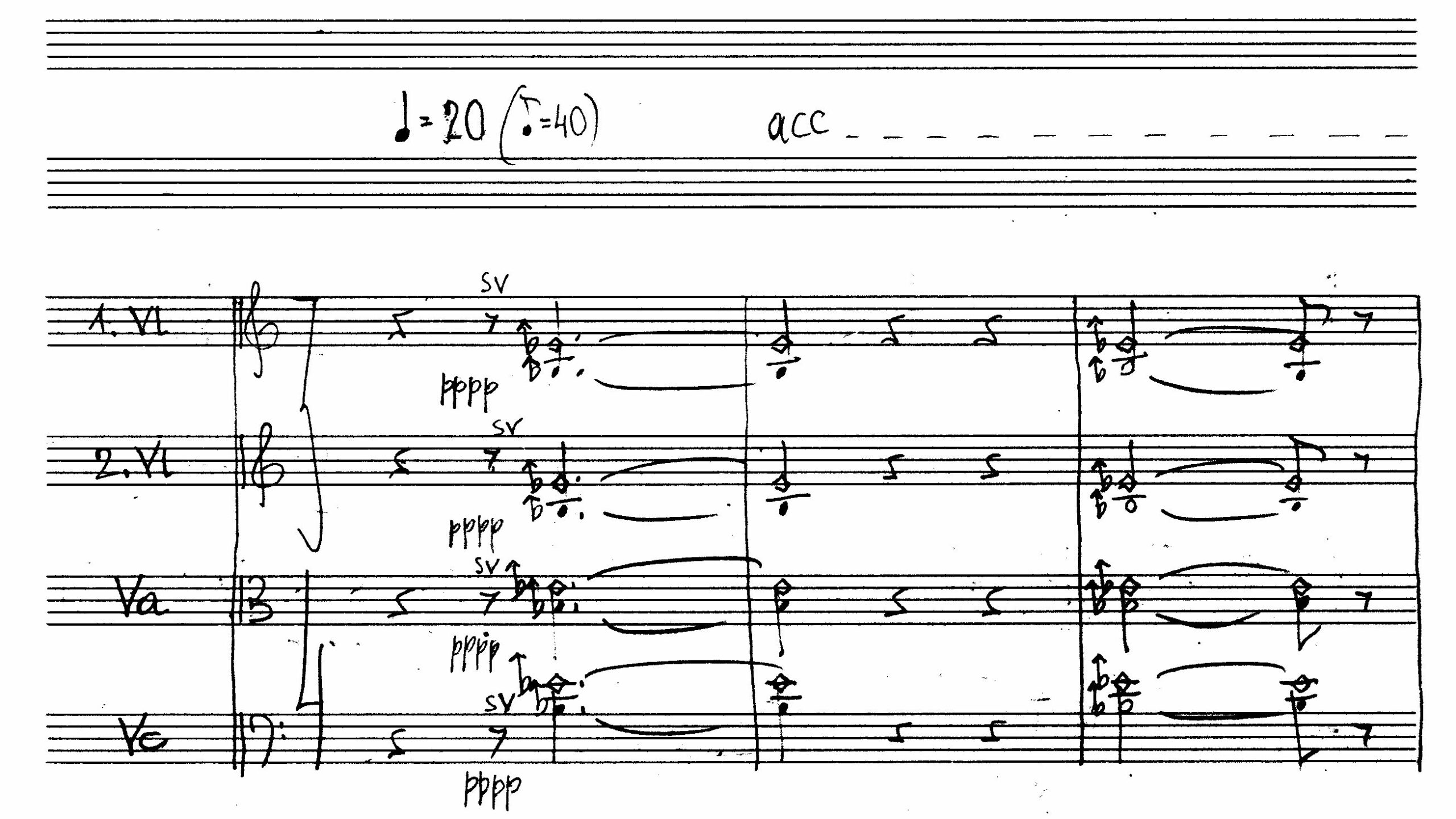

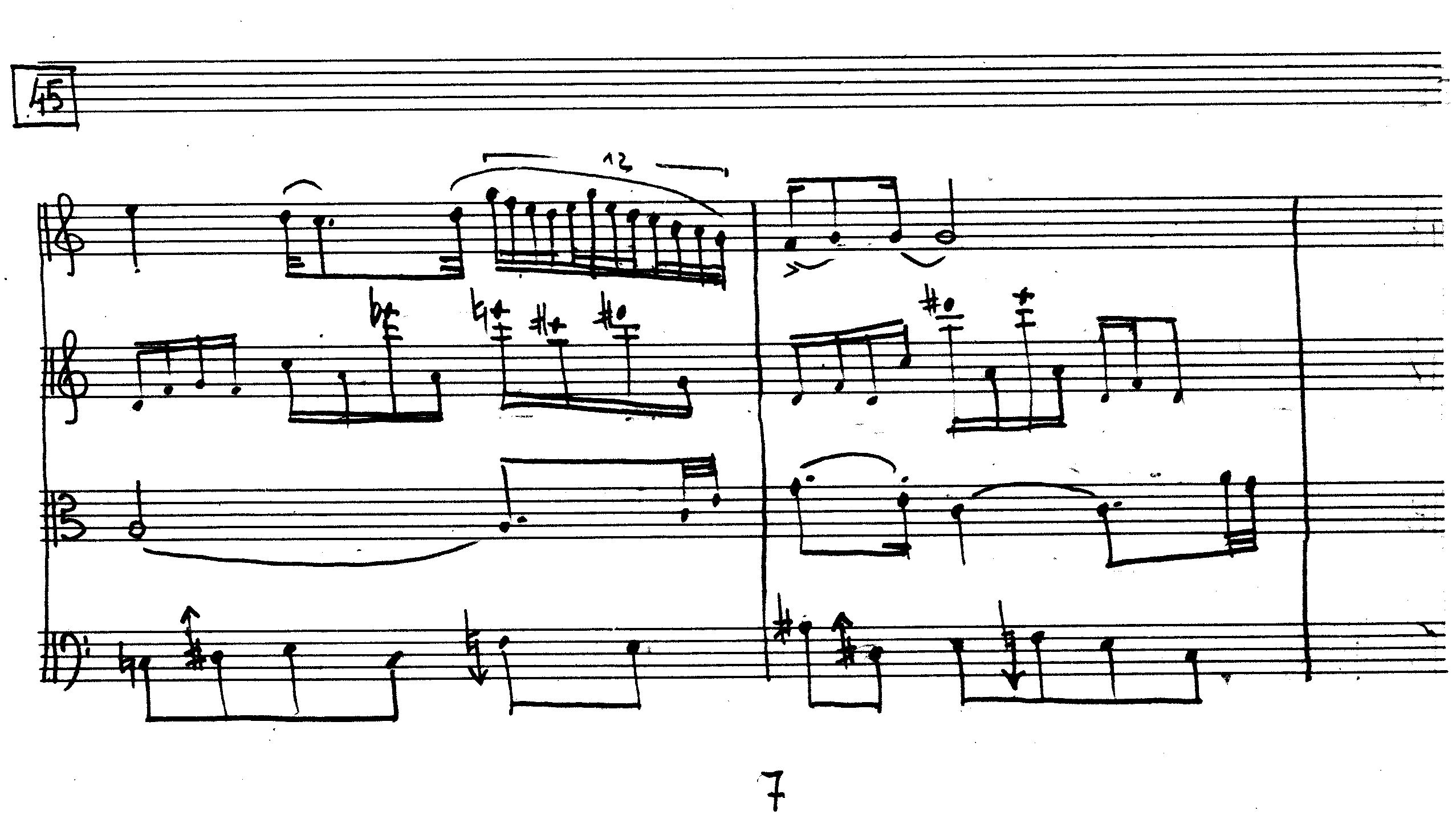

Cerha, 2. Streichquartett, T. 1-19

About the music

Emerging from the dark: The first notes are barely audible, spaced apart by complete silence. An aural film is carefully unfurled using the most delicate of shades, misty and veiled. This early world of sound is shrouded in mystery, with neither contours nor tumult. In this way, Cerha opens the door to the music of the Iatmul people, which seems to arrive on the winds from afar. The special charm of this beginning arises from its timbre: For a long while, everything we hear emerges from an extremely fine harmonic field and the animated overtones of the stringed instruments. Ligeti was fascinated by the magic of Papua New Guinea’s overtone music, while Cerha also highlights the Iatmul’s microtonal scales, which shimmer through at the beginning of the piece. Many of the harmonic tones are shifted from the Western ideal in quarter-tone steps, thus building an acoustic atmosphere that feels foreign, unfamiliar. Cerha’s process-based thinking can be heard in the opening passage. All four strings begin on the same note, E flat, in striking resemblance to the “Maqam” quartet, which is initiated by a long E played by all musicians. Here too, individual voices emerge from the uniformity. A fifth is played first, which the quarter tones make “too tight”,[1] resulting in a ghostly effect. This transparency is immediately discarded in favour of a dense band of sound in which the individual voices oscillate between just a few tones. Only the cello has begun moving towards something new, slowly detaching itself from the fragile world of overtones …

[1] Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 261

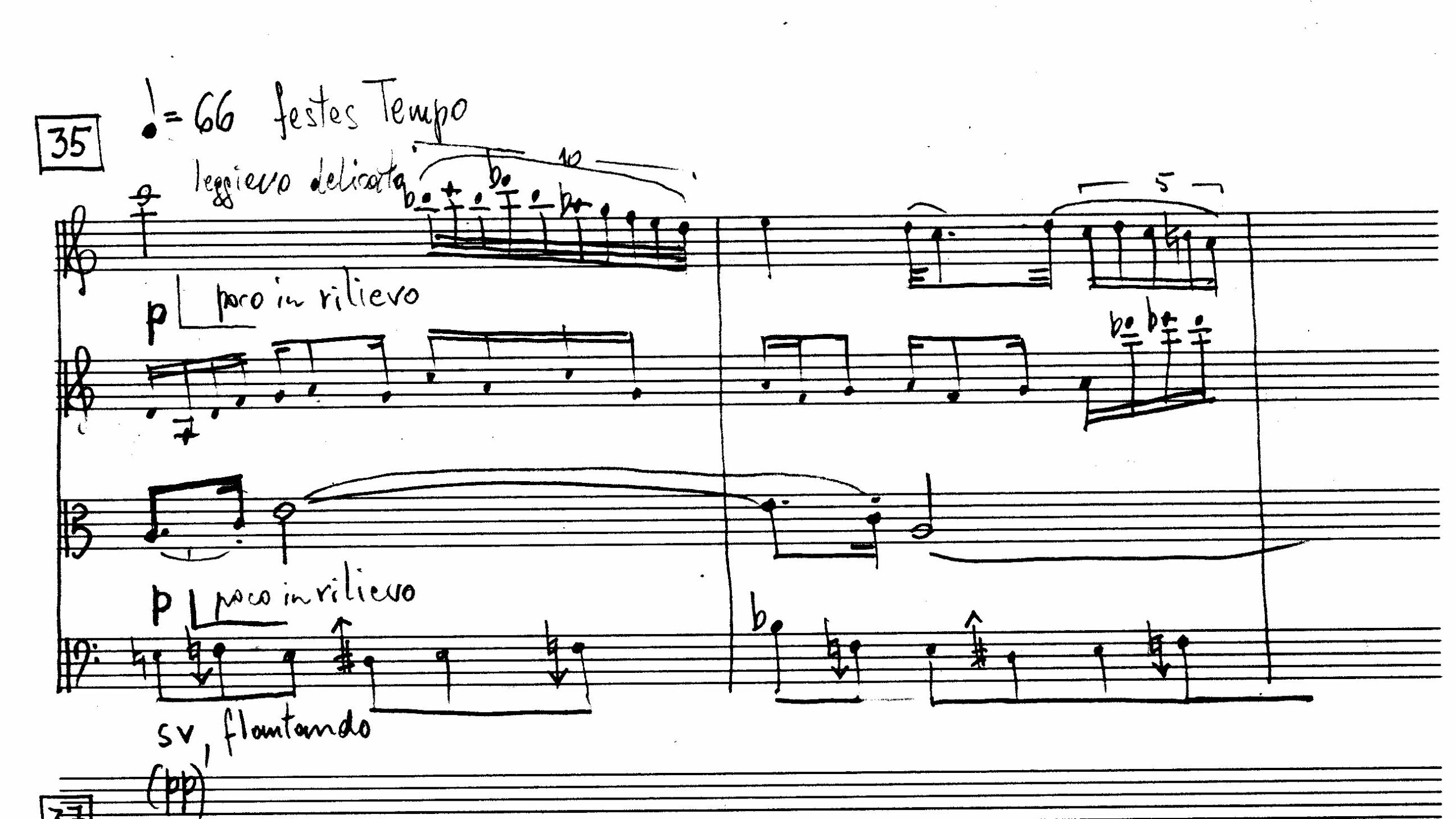

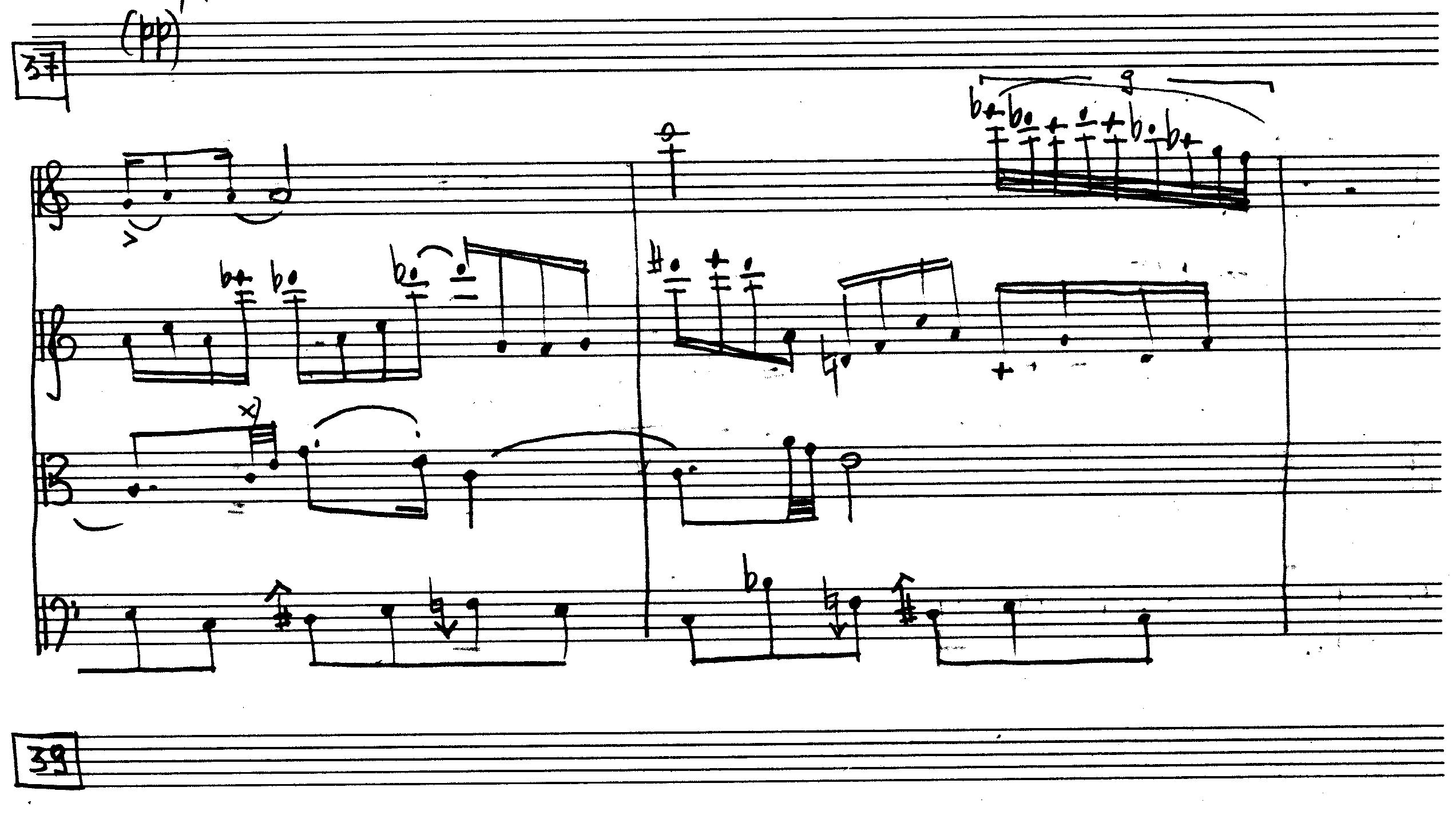

Station No. 2: Music of Many Gestures

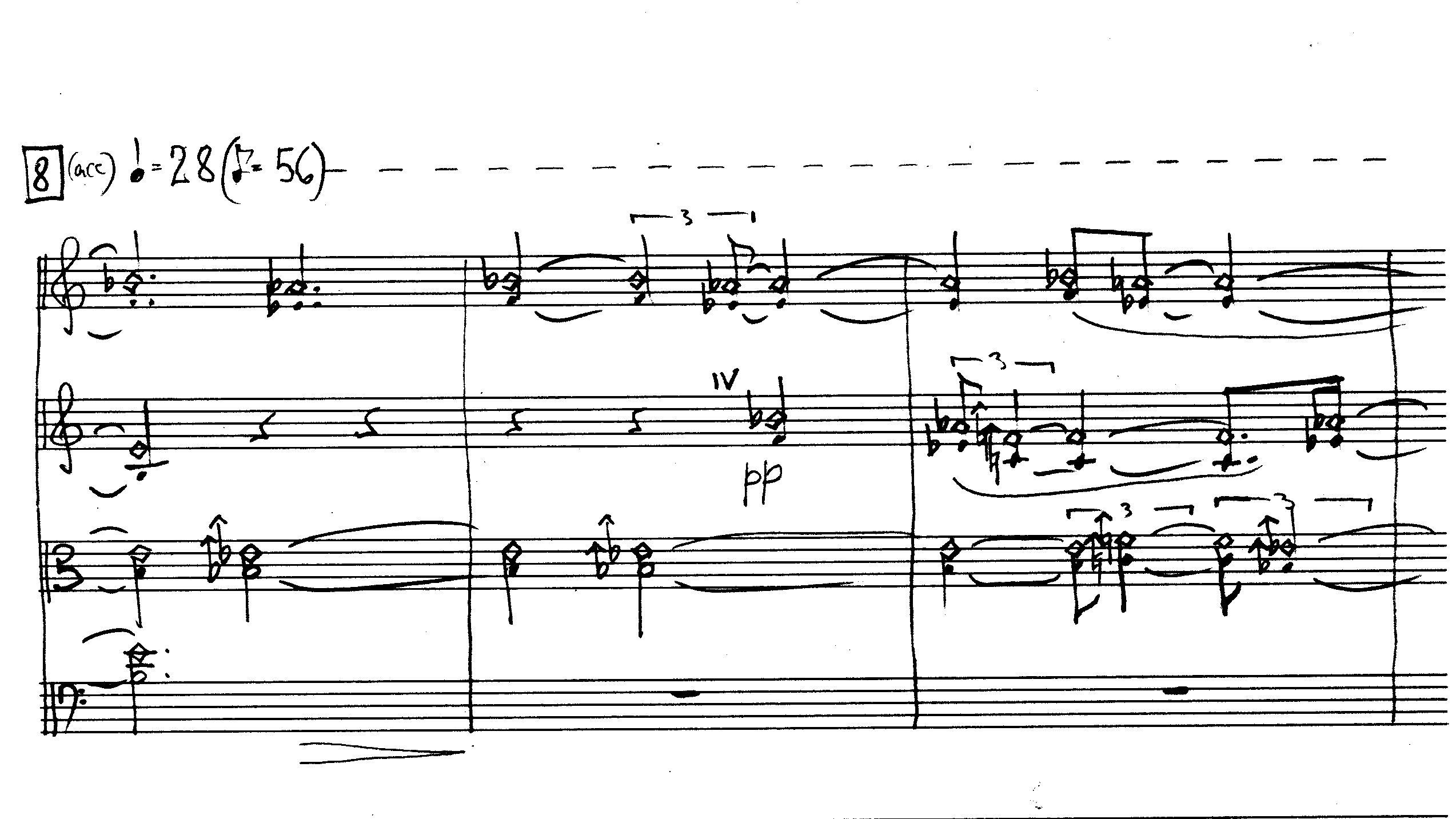

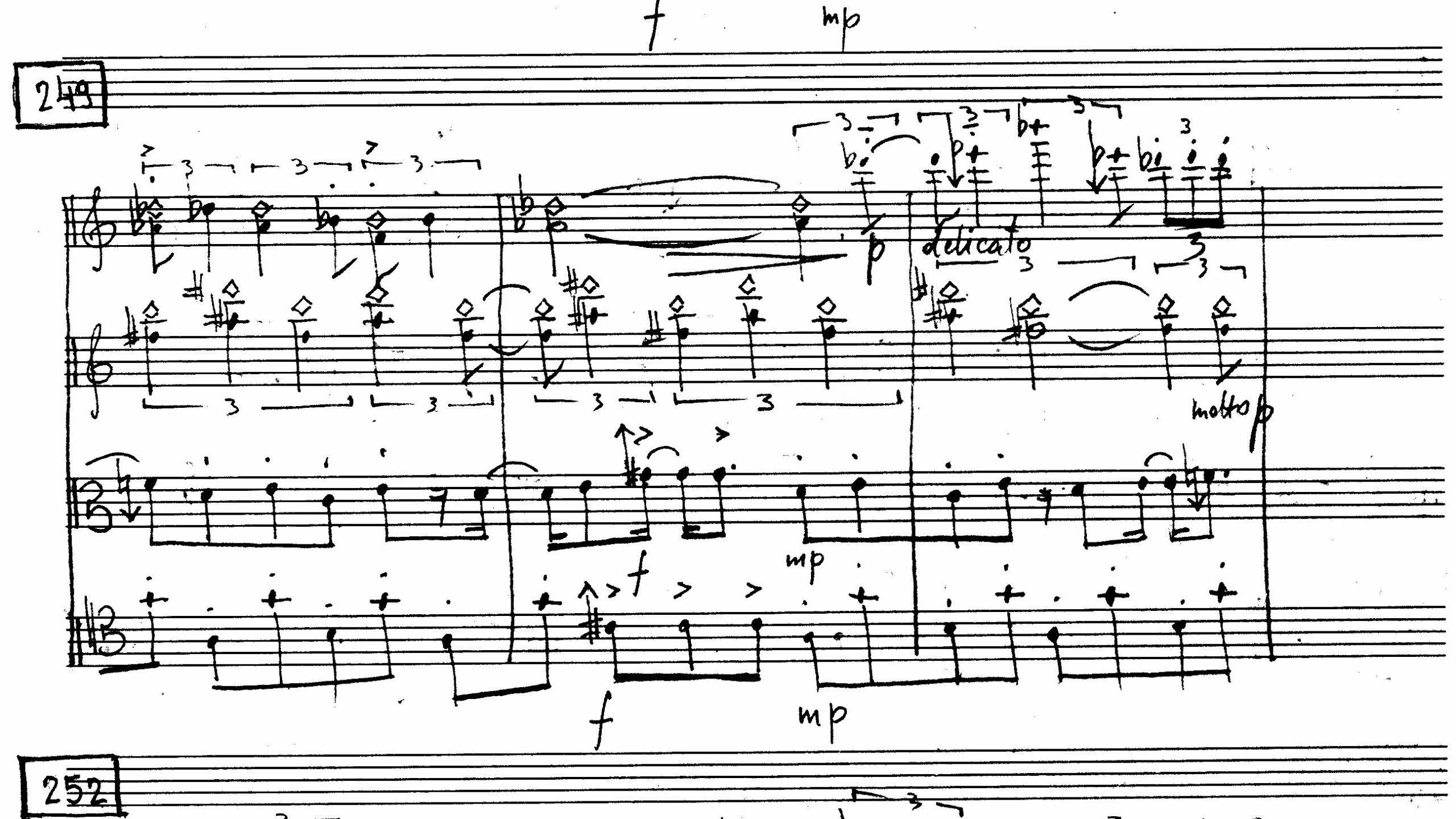

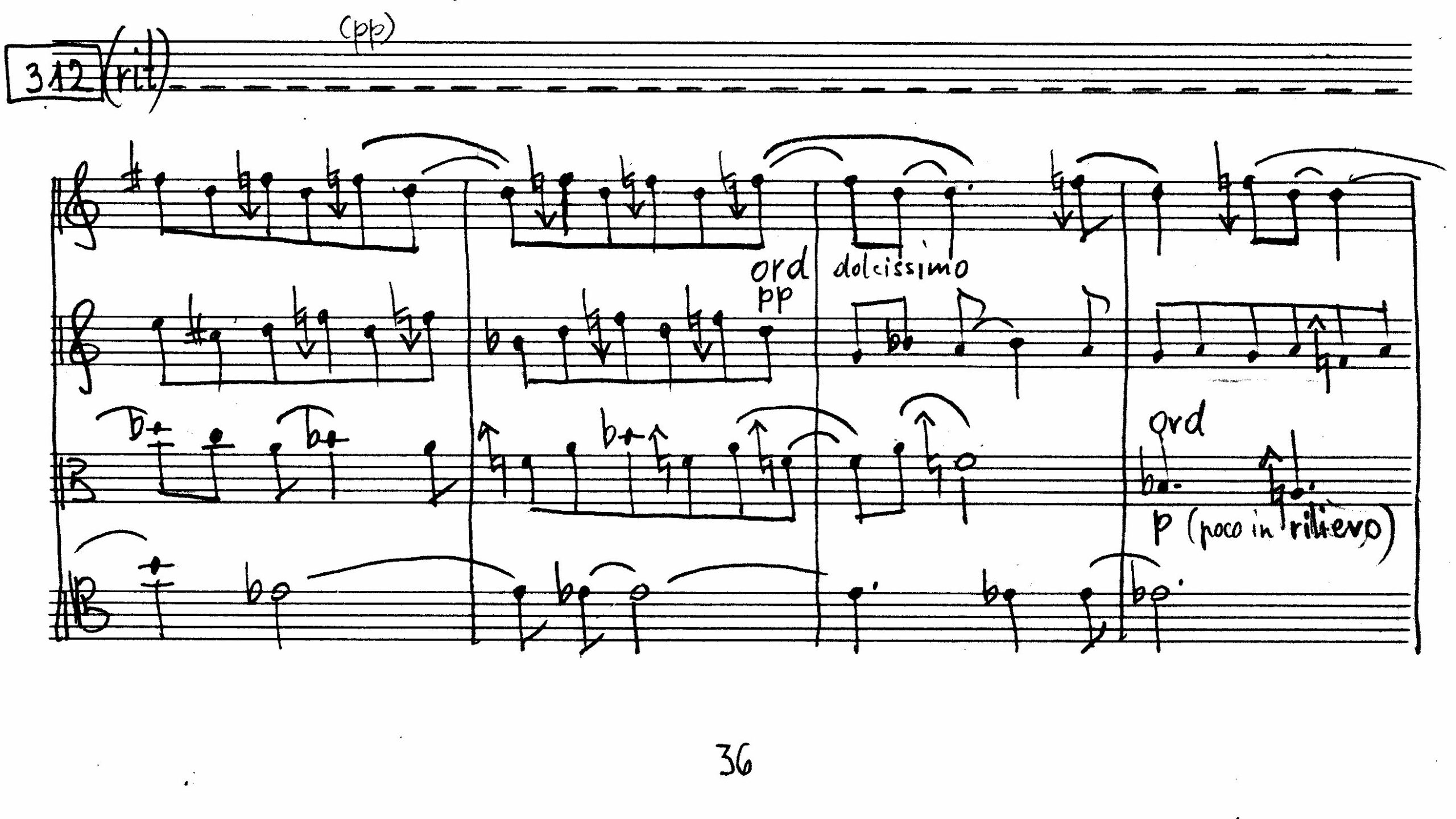

Cerha, 2. Streichquartett, T. 35-48

About the music

From this starting point of surreal faraway island sounds, the music continues rushing forward until it flows into a new stage. Here reigns not only a “fixed tempo”, but also a fixed character, one that somehow embodies diversity as well. As in the opening section, the four strings combine to create an interwoven fabric of sound. In the first violin, shimmering ornaments; in the second, continuous jumps; in the viola, sustained tones; and in the cello, a series of eighths. Cerha describes the music as polygestic: “There are not only constant polymetric formations, layers of different metrics atop one another, but the type of musical movement, of musical gestures in each instrument is also different.”Cerha, commentary on Zweiten Streichquartett, AdZ, 000T0105/4 A chain of nested “melodic phrases”Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 261 draws its inspiration from the music of the Iatmul. The deep voices, in particular the viola and cello, have a Papuan touch, continually oscillating between the same tones. While the viola acts like a flute, picking up on a typical Oceanic rhythm also heard in the soon to be composed Phantasiestück in C.’s Manier, the cascade of cello notes is comprised mainly of quarter tones. There is, however, no rigid repetition of these formulas; variations ensure that the inner ribbon of sound remains malleable.On the melodic “striking method”, see: Lukas Haselböck, “Zum Erleben von Prozessen: Cerhas 2. Streichquartett und Phantasiestück in C.’s Manier”, in: Haselböck, (ed.): Friedrich Cerha. Analysen, Essays, Reflexionen, Freiburg et. al 2006, pp. 95–120, here p. 98 ff

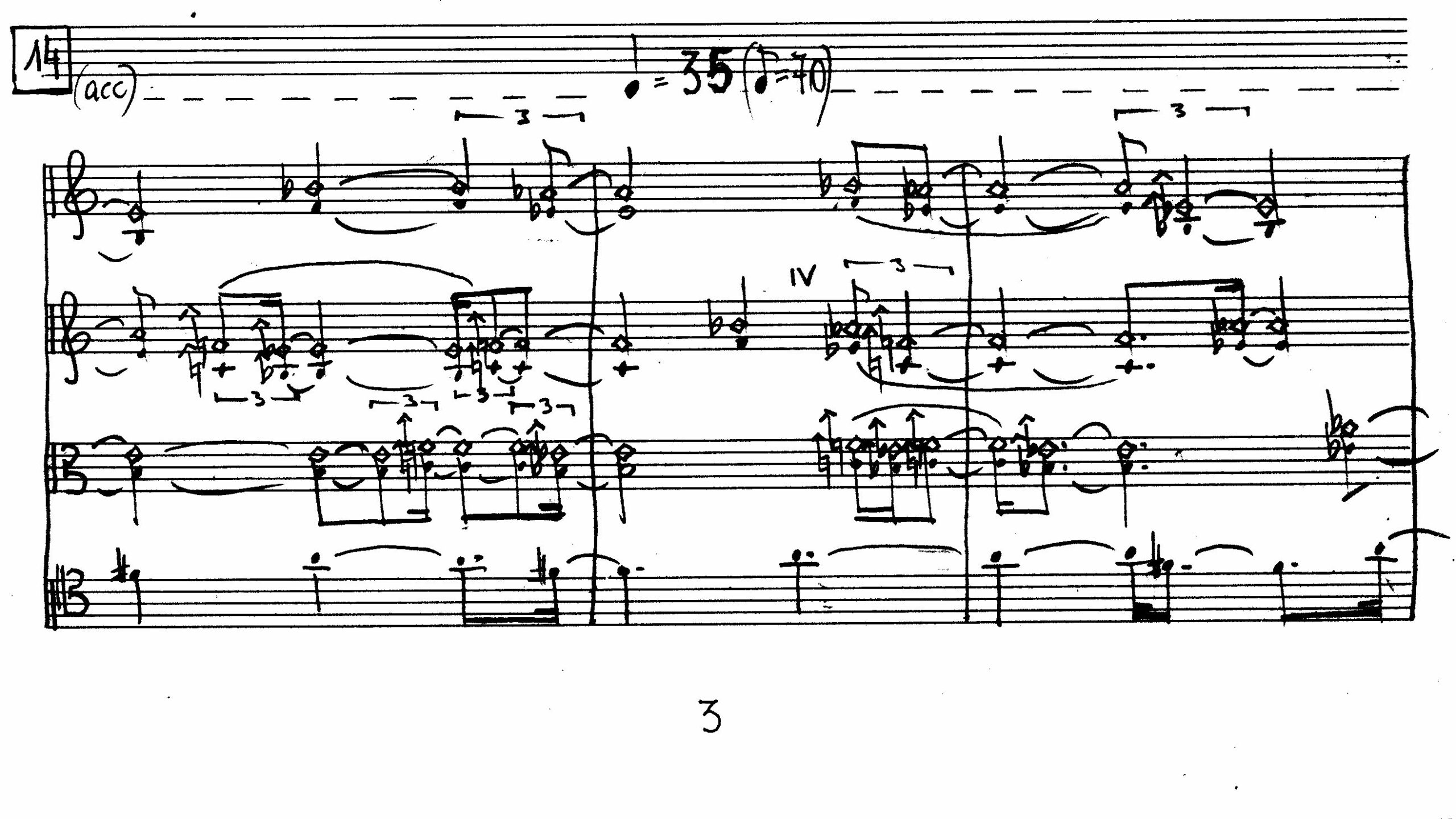

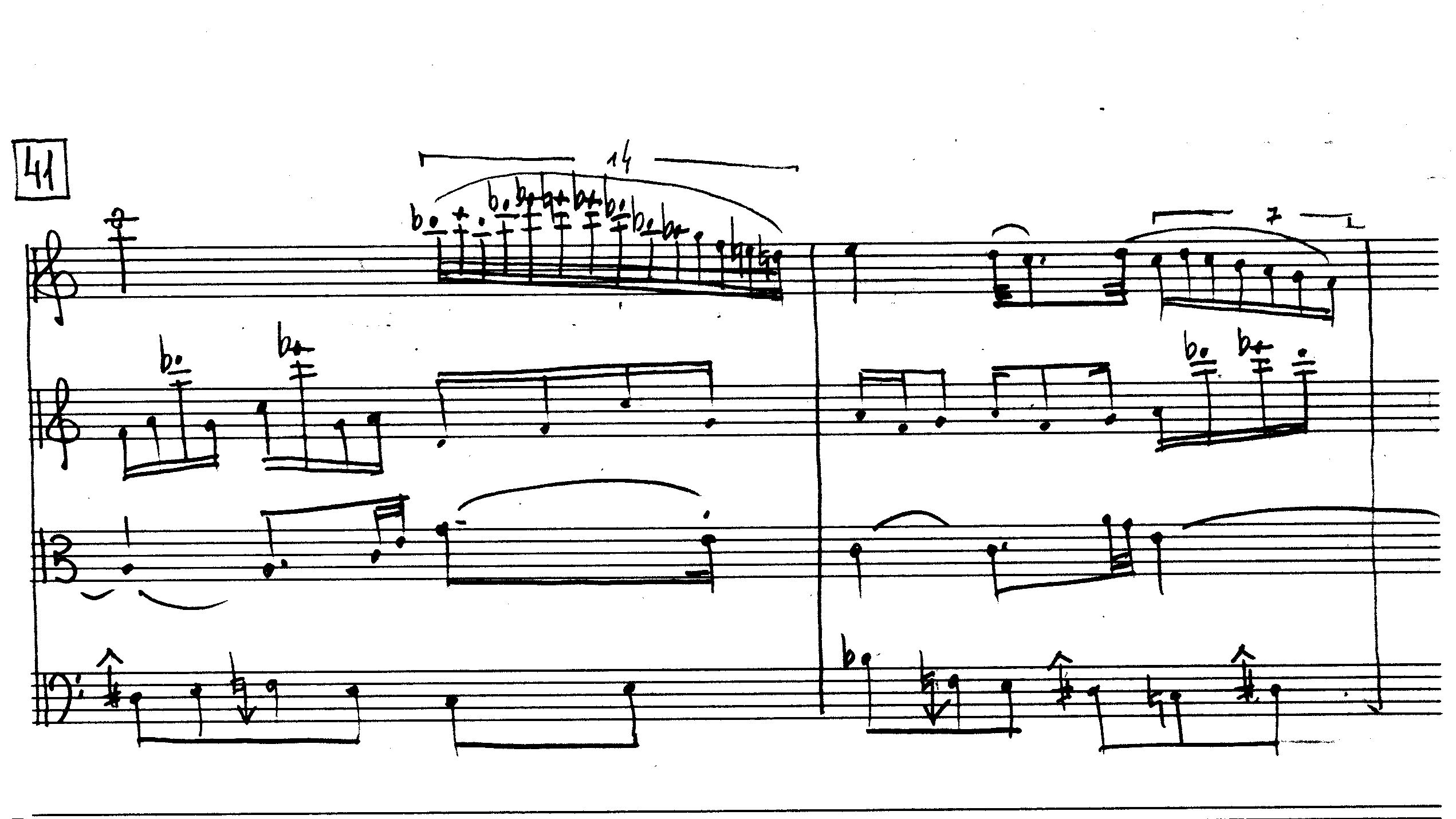

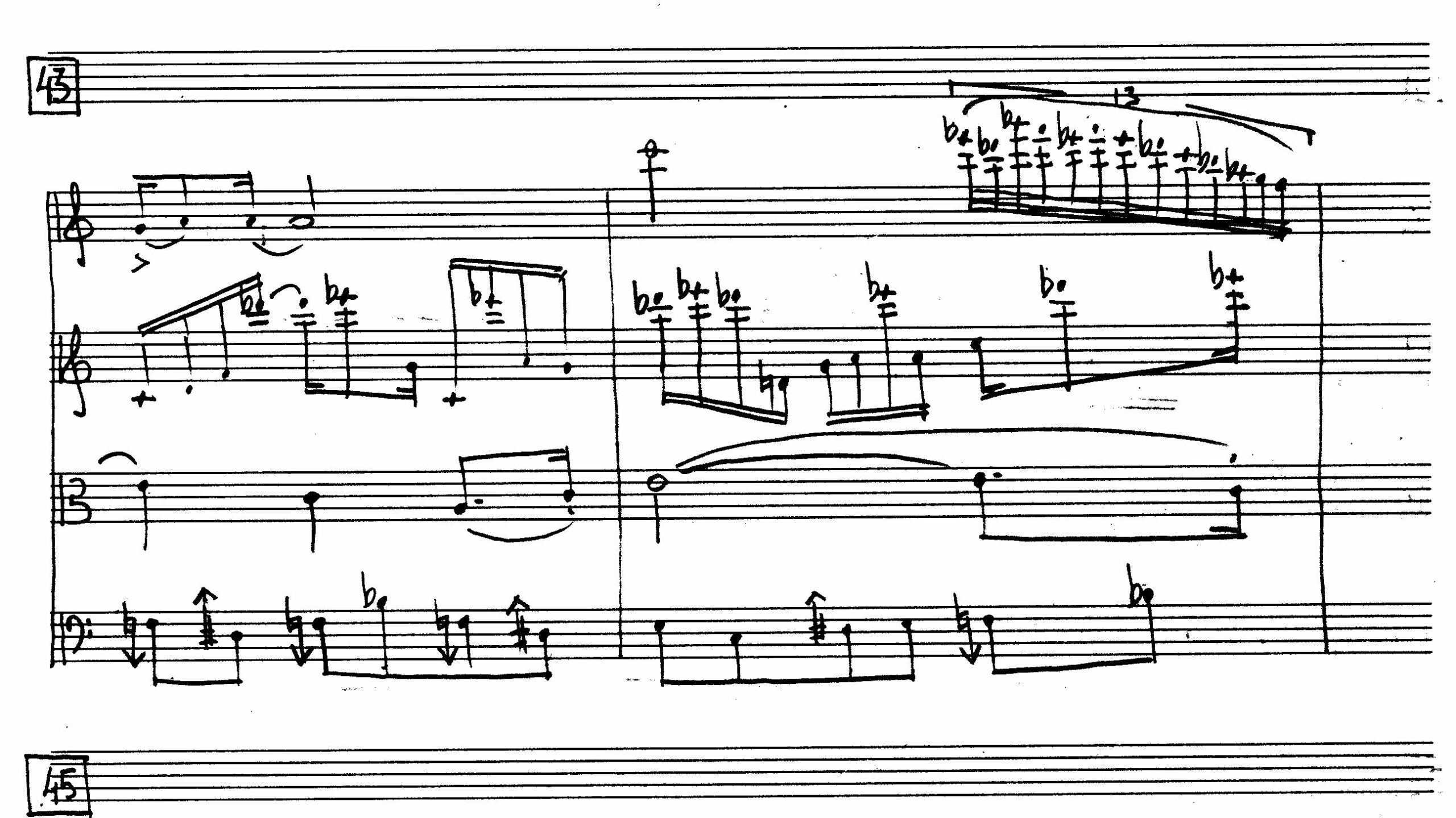

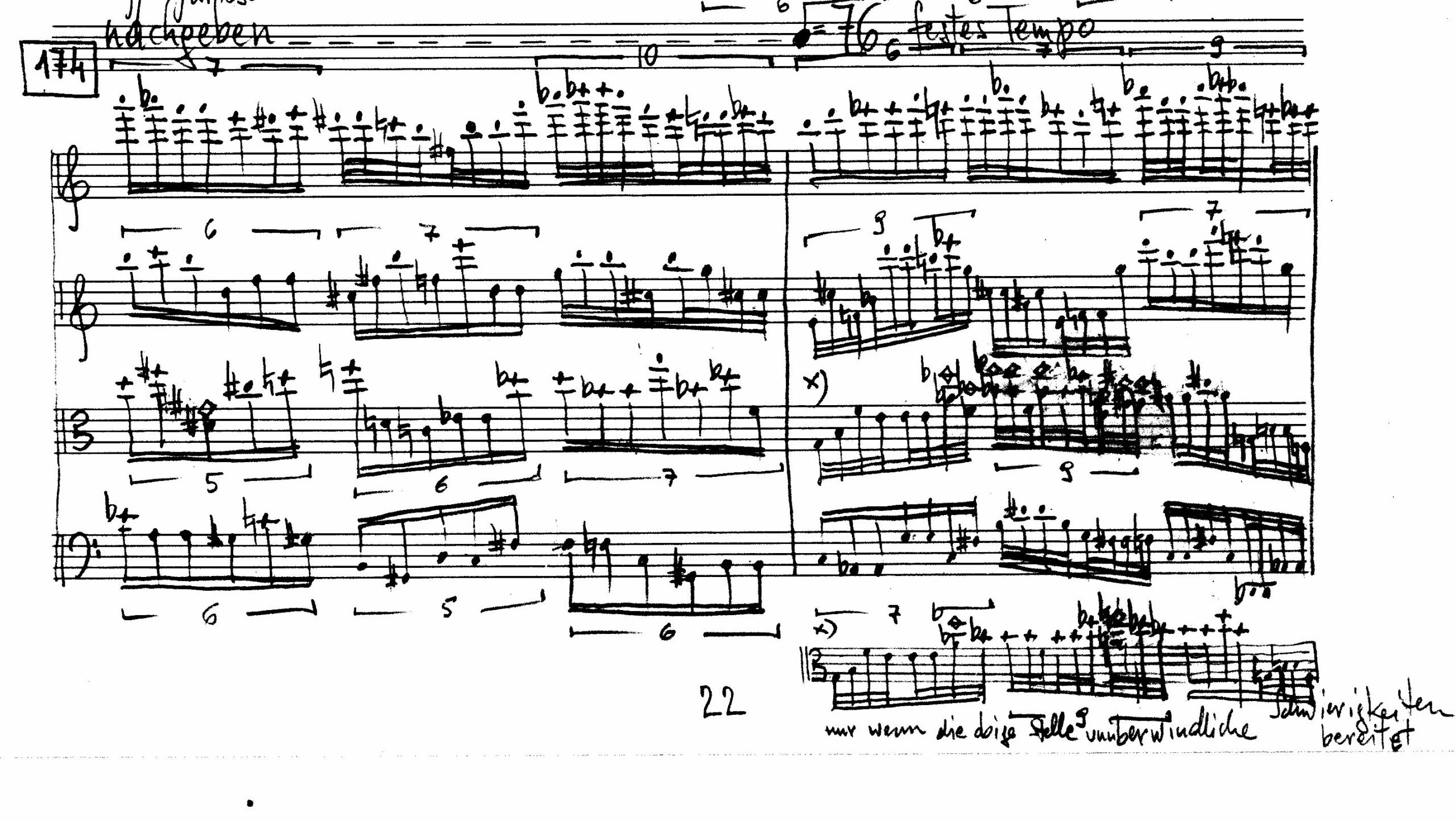

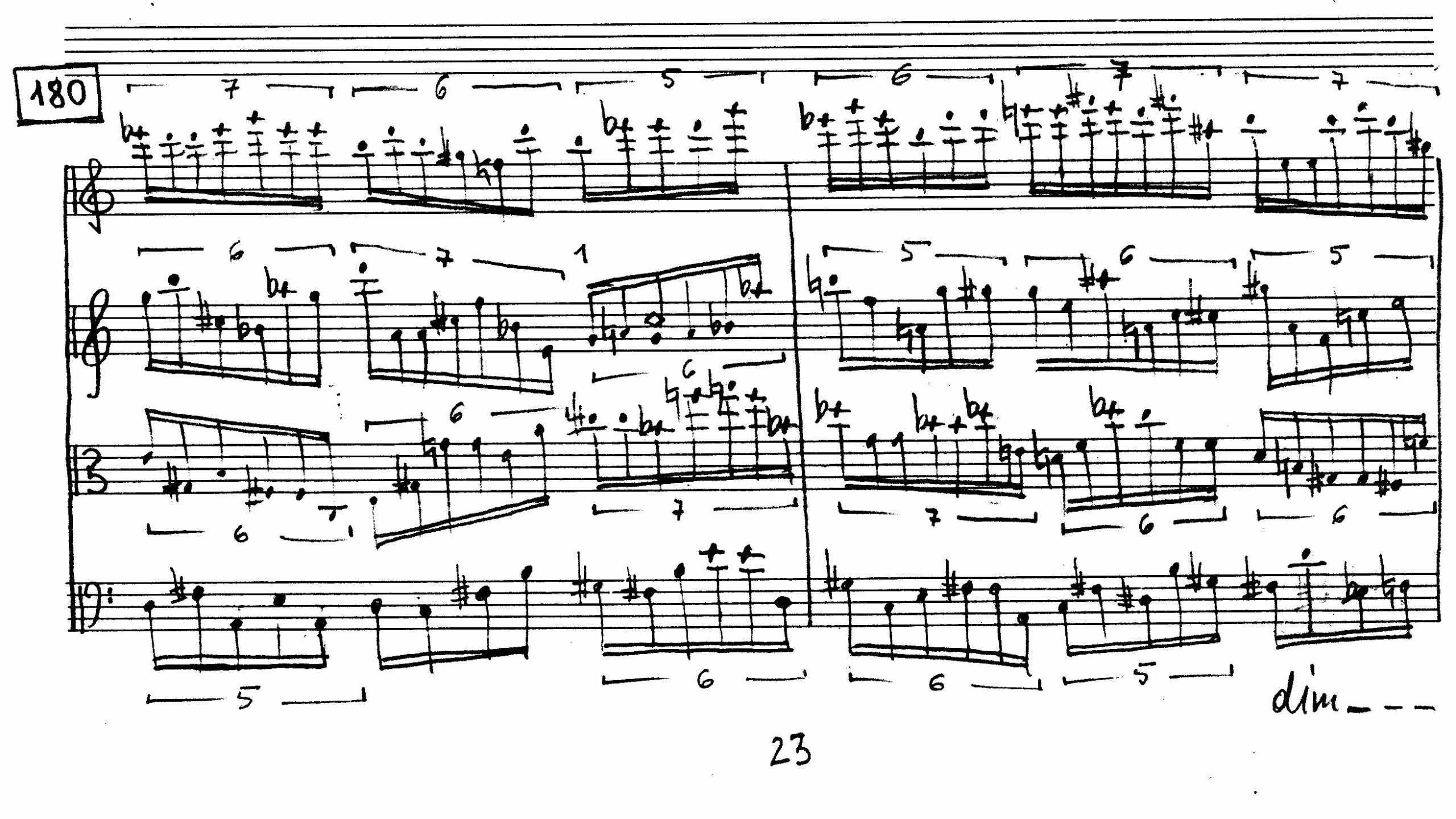

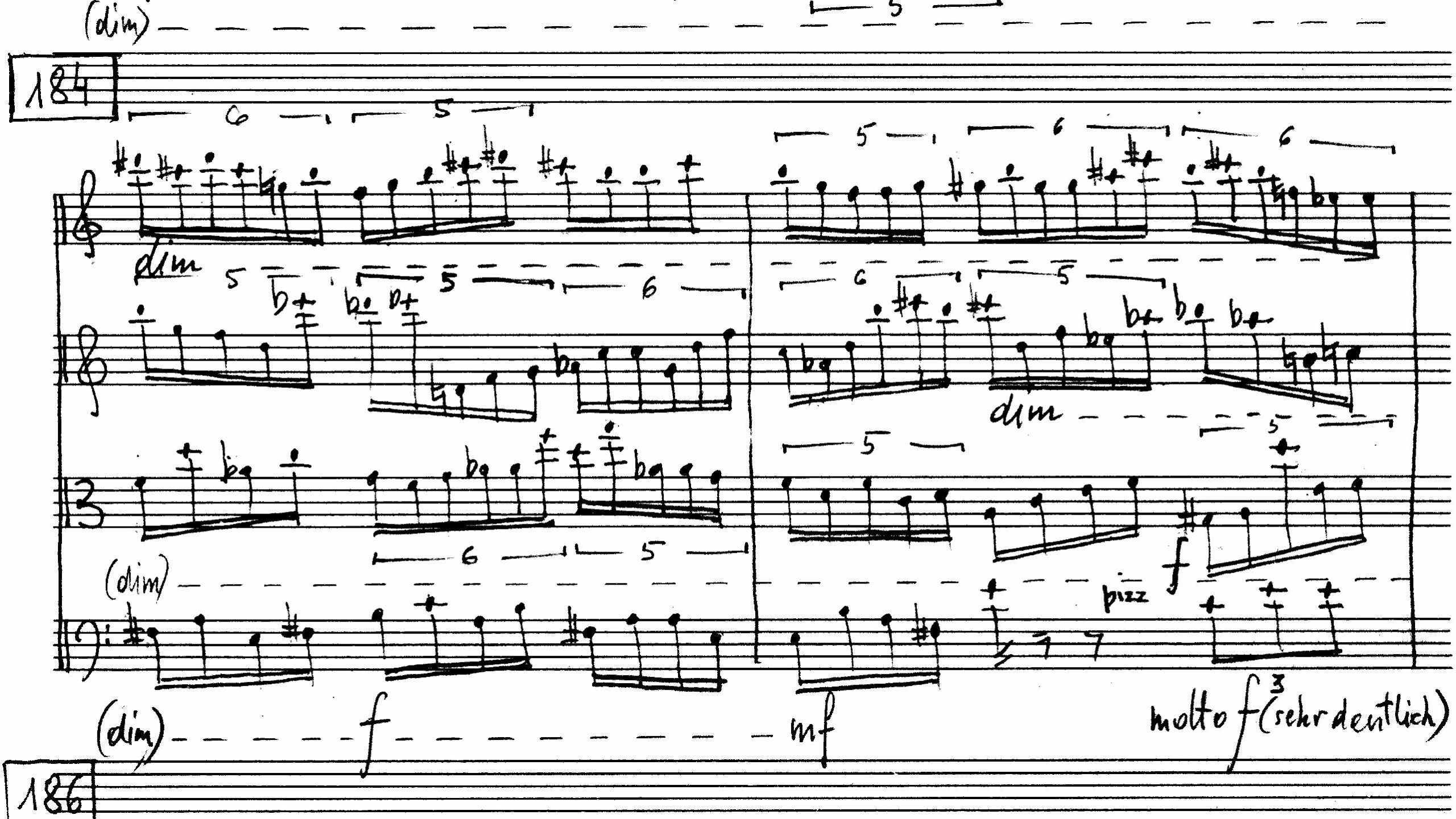

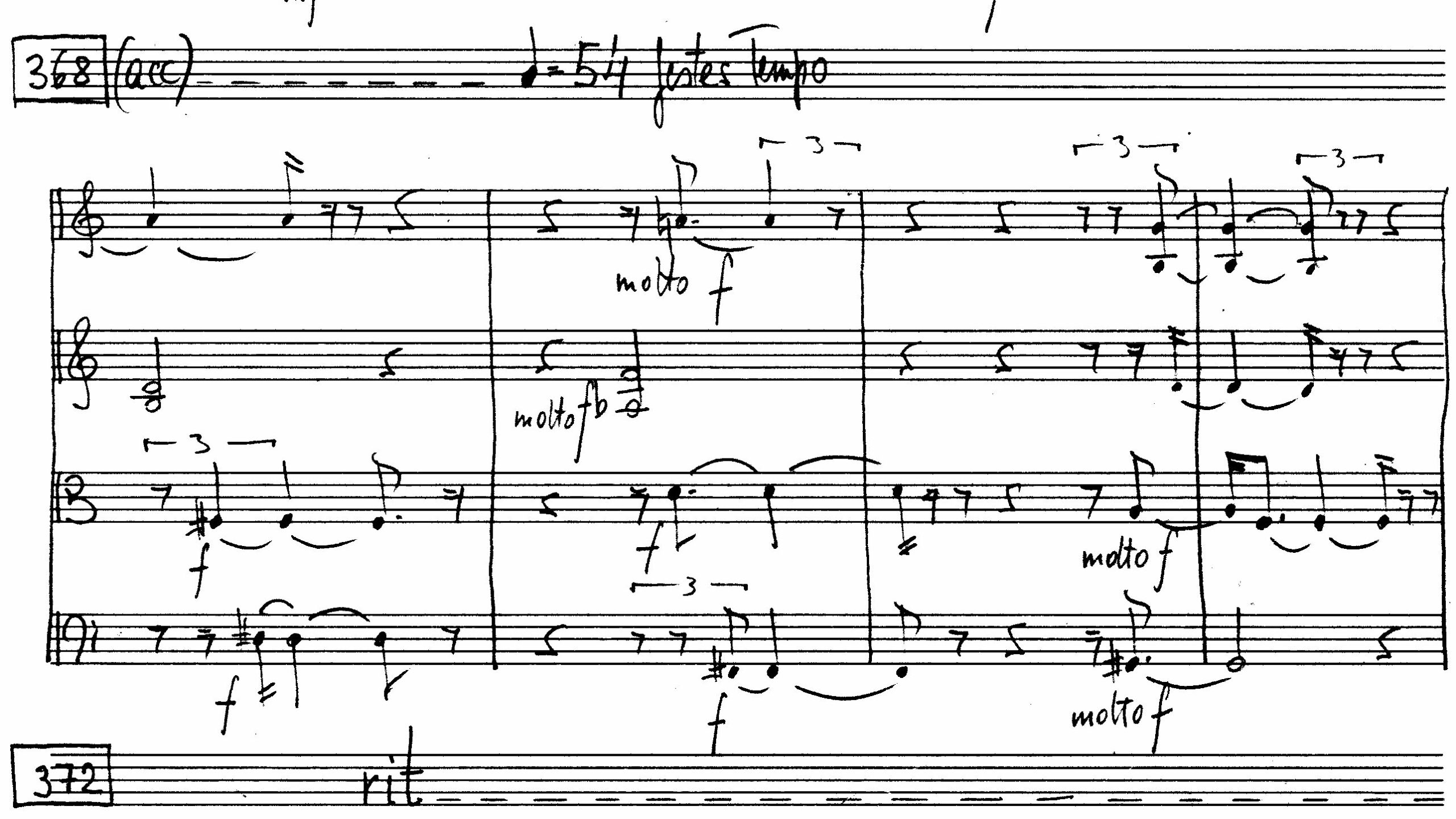

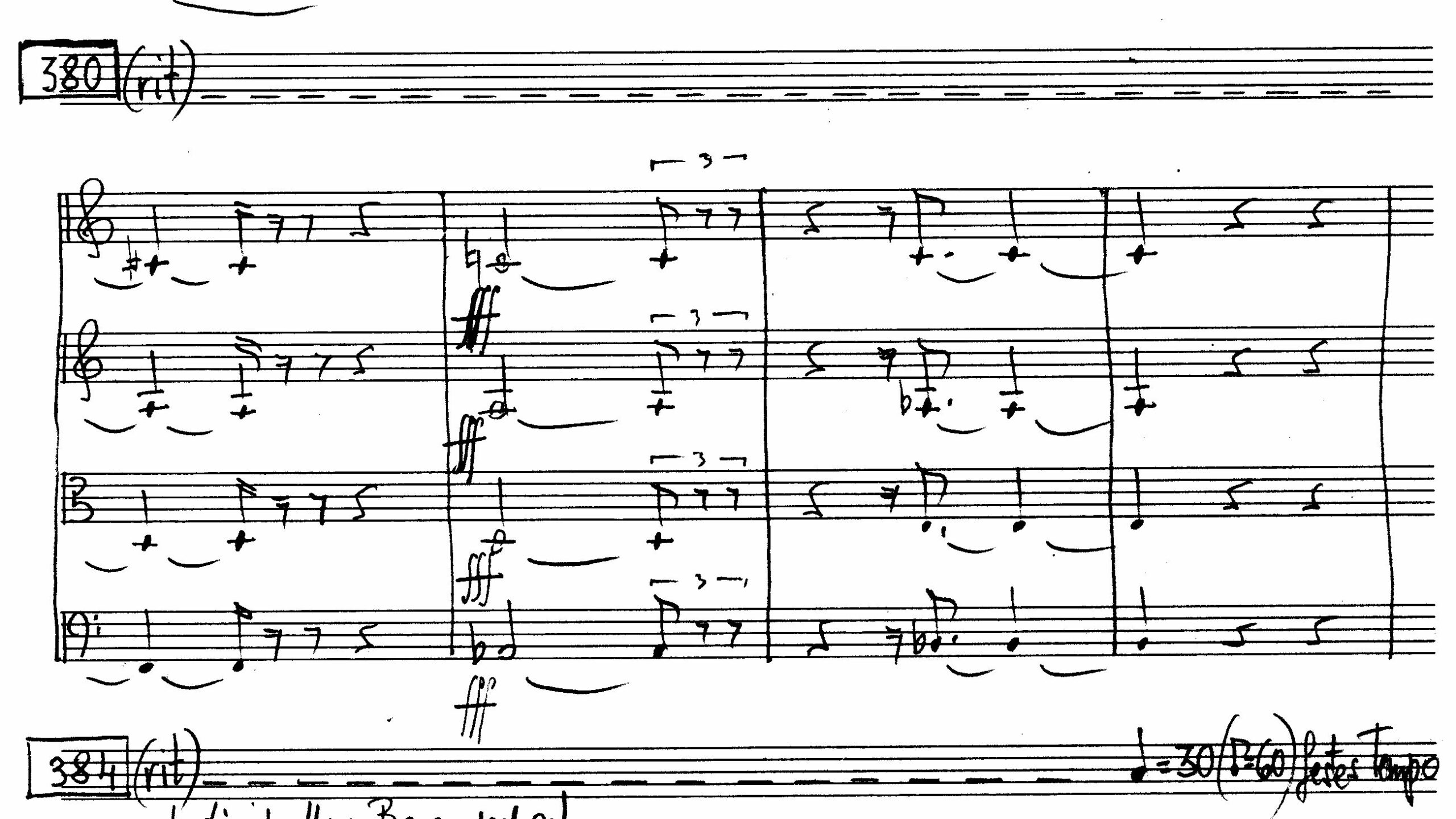

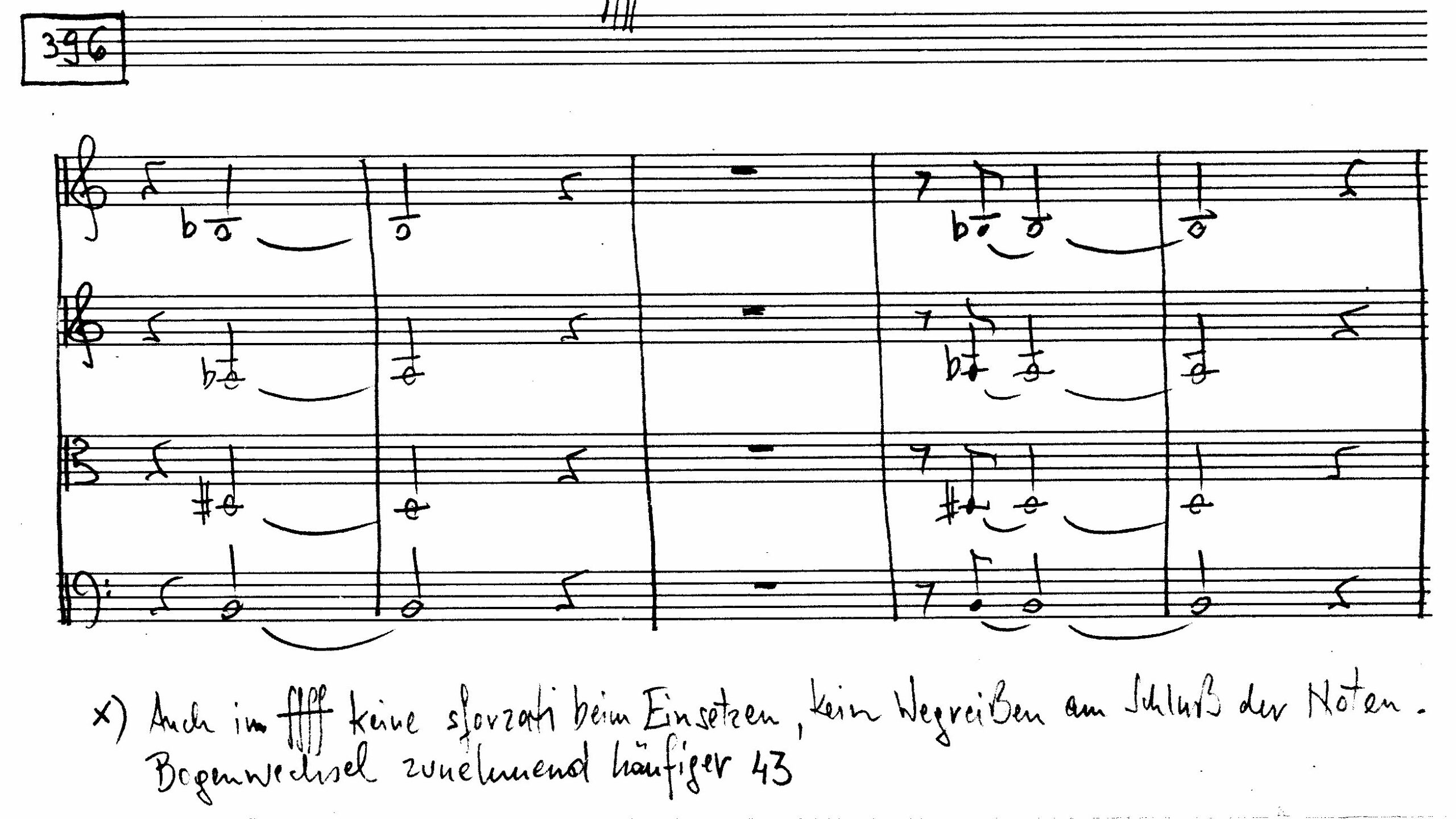

Station No. 3: Furioso

Cerha, 2. Streichquartett, T. 172-187

About the music

The quartet’s broad arc of tension leads to a liberation of musical energy roughly in the middle. Cerha titles this climax “Furioso” (stormy, with a wild temper). The polygestive character pauses entirely—instead, the four strings are woven together into a tangled web of sound, individual tones no longer distinguishable. Something similar happens in Phantasiestück in C.’s Manier: An “accelerating melodic network” is dissolved “in a tangle of movements”,[1] before this unwinds again and the music begins to calm. The unrestrained gestures become even harder, edgier. All strings play continuously in fortissimo; there are no moments of rest; a monolithic, unbreakable block of sound arises. The lines rush forward, collide dissonantly, and the energy does not ease until some time has passed. All this is far removed from the Papuan influences of the quartet’s first movements.

[1] Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 262

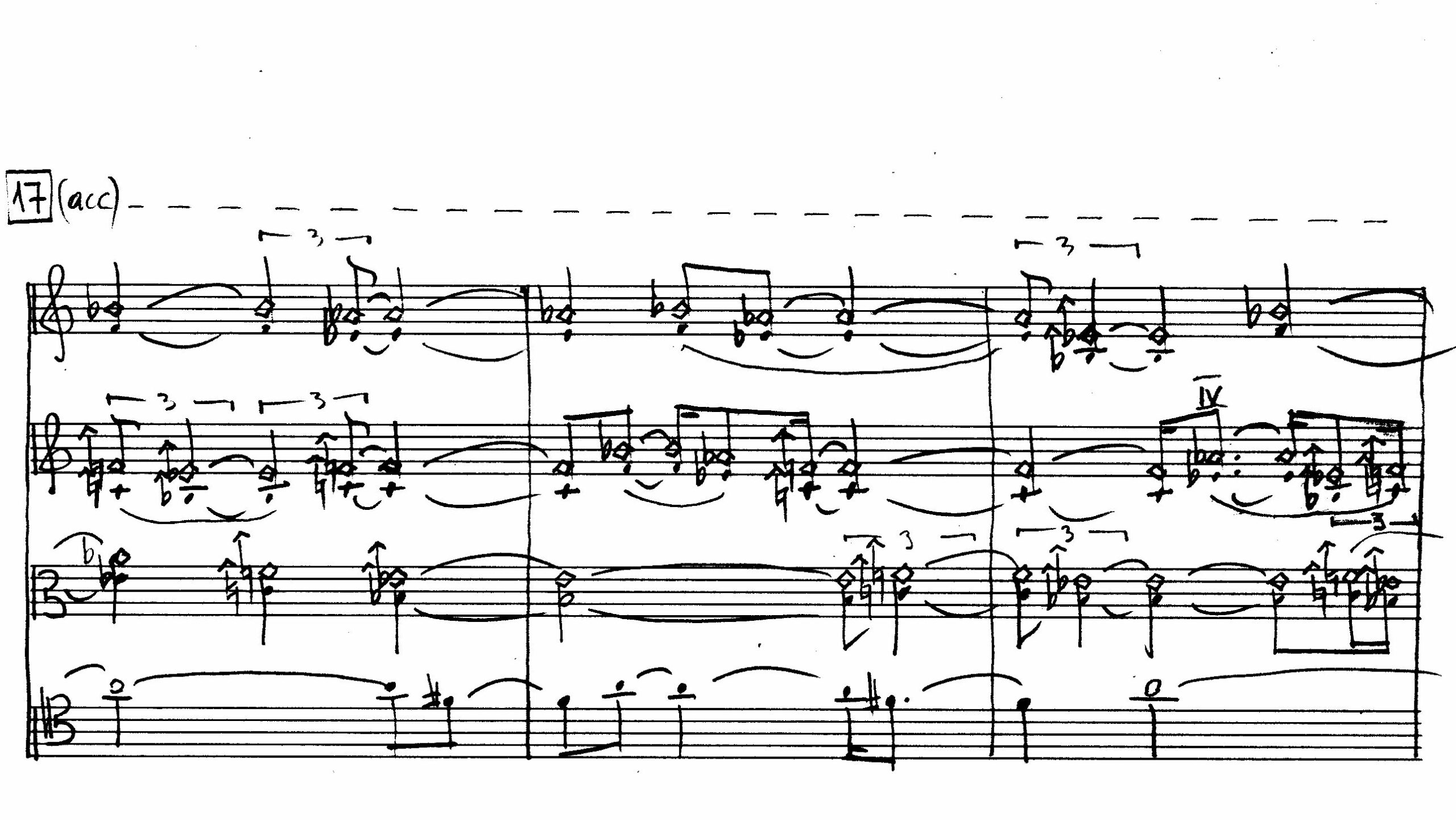

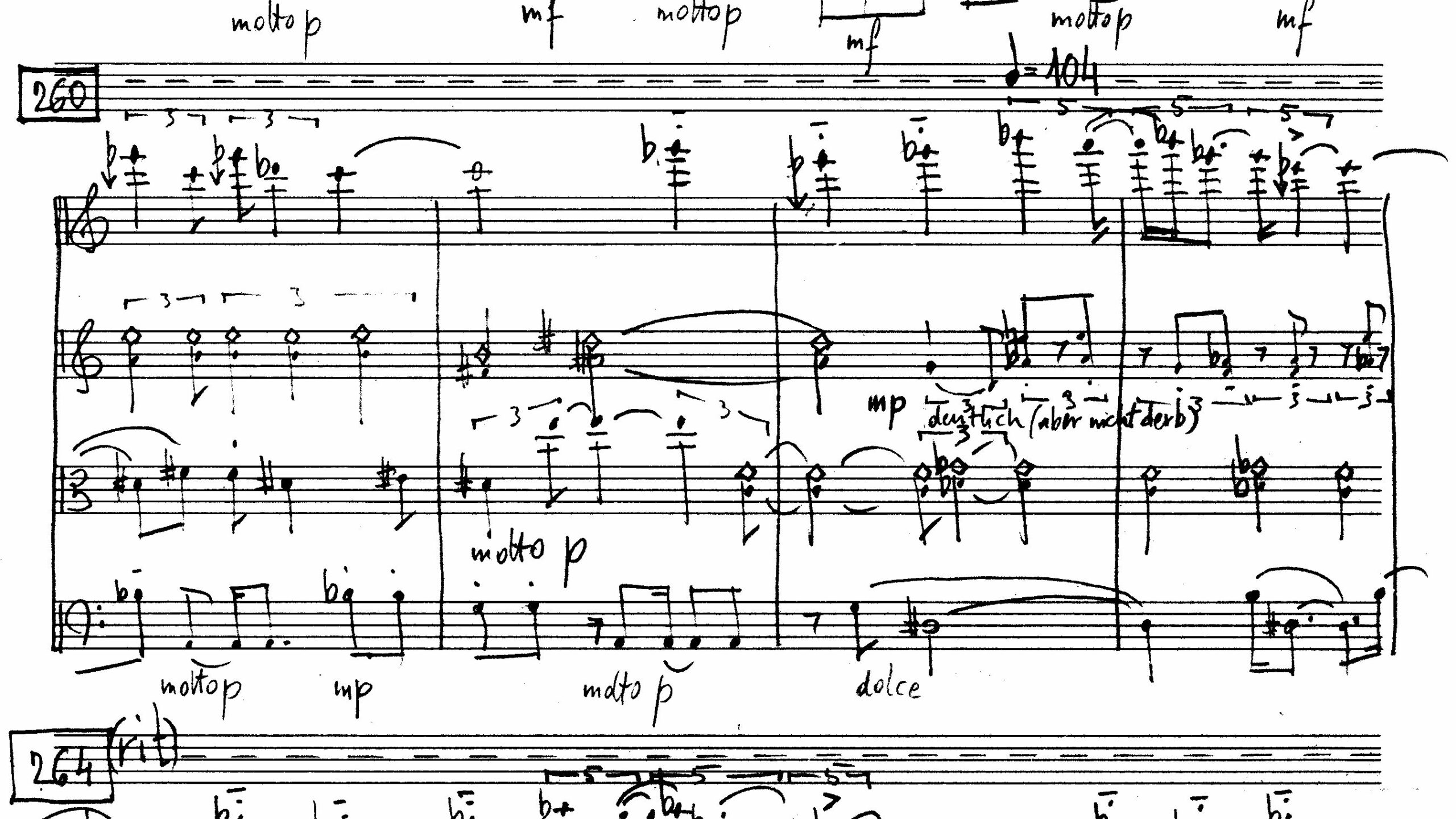

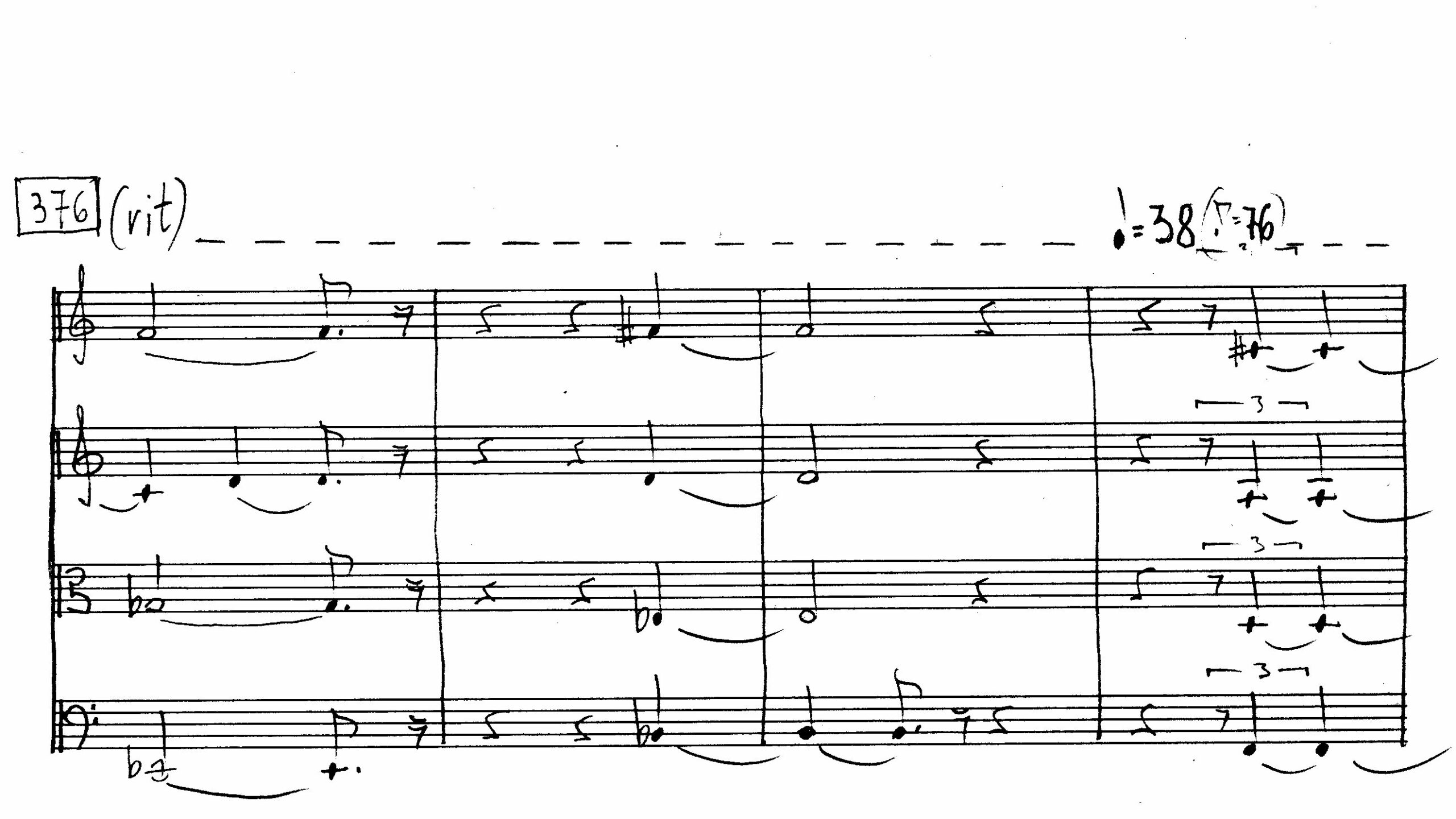

Station No. 4: Sound in the Wind

Cerha, 2. Streichquartett, T. 246-267

About the music

There is a constant flux in the interplay between a more European musical perspective and one that draws upon the sounds of Oceania. After the climax of “Furioso”, the music recedes steadily back in the other direction. The intensity decreases; relaxation sets in. The connections to the acoustic world of the Iatmul become stronger, measured by the increased overtone sounds of the two violins and accompanied anew by polygestic melodic phrases. In a steady procession, each string circles back to its individual movement profile. The use of melodic building blocks in ostinato becomes even more pronounced than in the first half, joined together in individual voices that continue almost unchanged, repeated over and over again. It is here that this circular concept of music that has no relationship to the straightforwardness of European culture comes into its own. Change is still possible, of course, yet it drifts off in the airiness of the overall sound. Sometimes it is scarcely noticeable when a string suddenly switches to a different melody, with the other voices still clinging to theirs. In this way, the acts of circling and moving forward are subtly united.

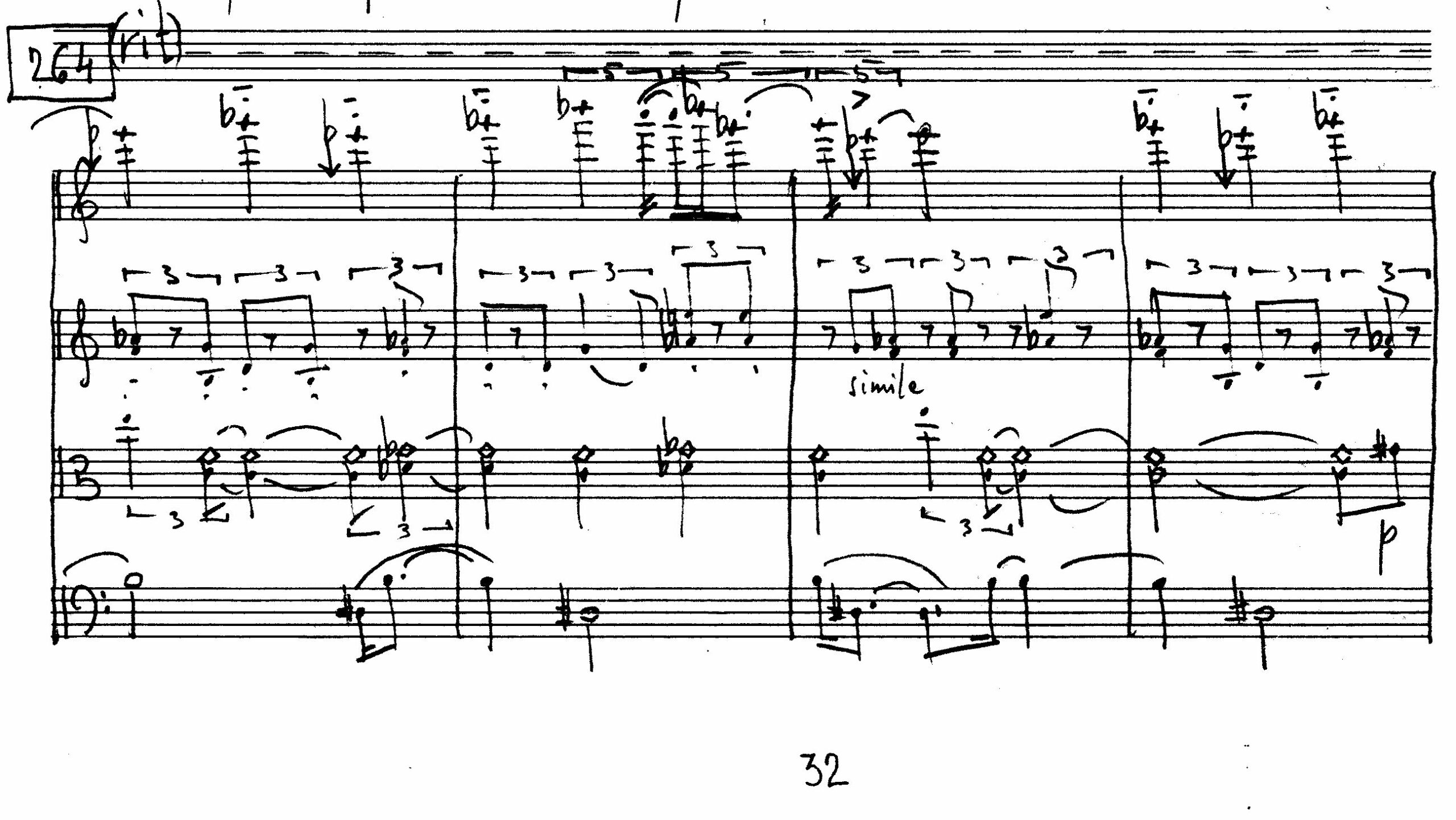

Station No. 5: Union

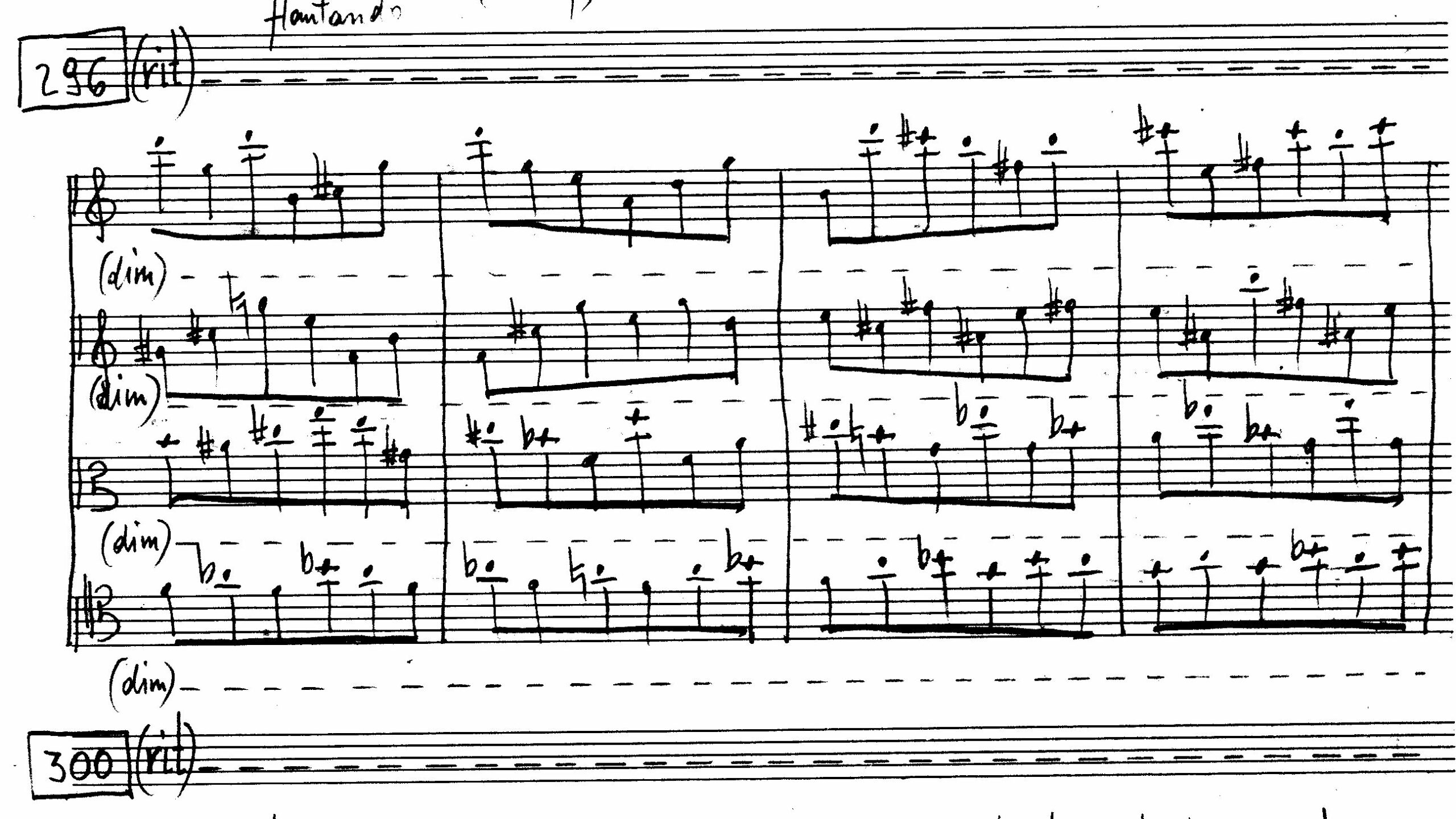

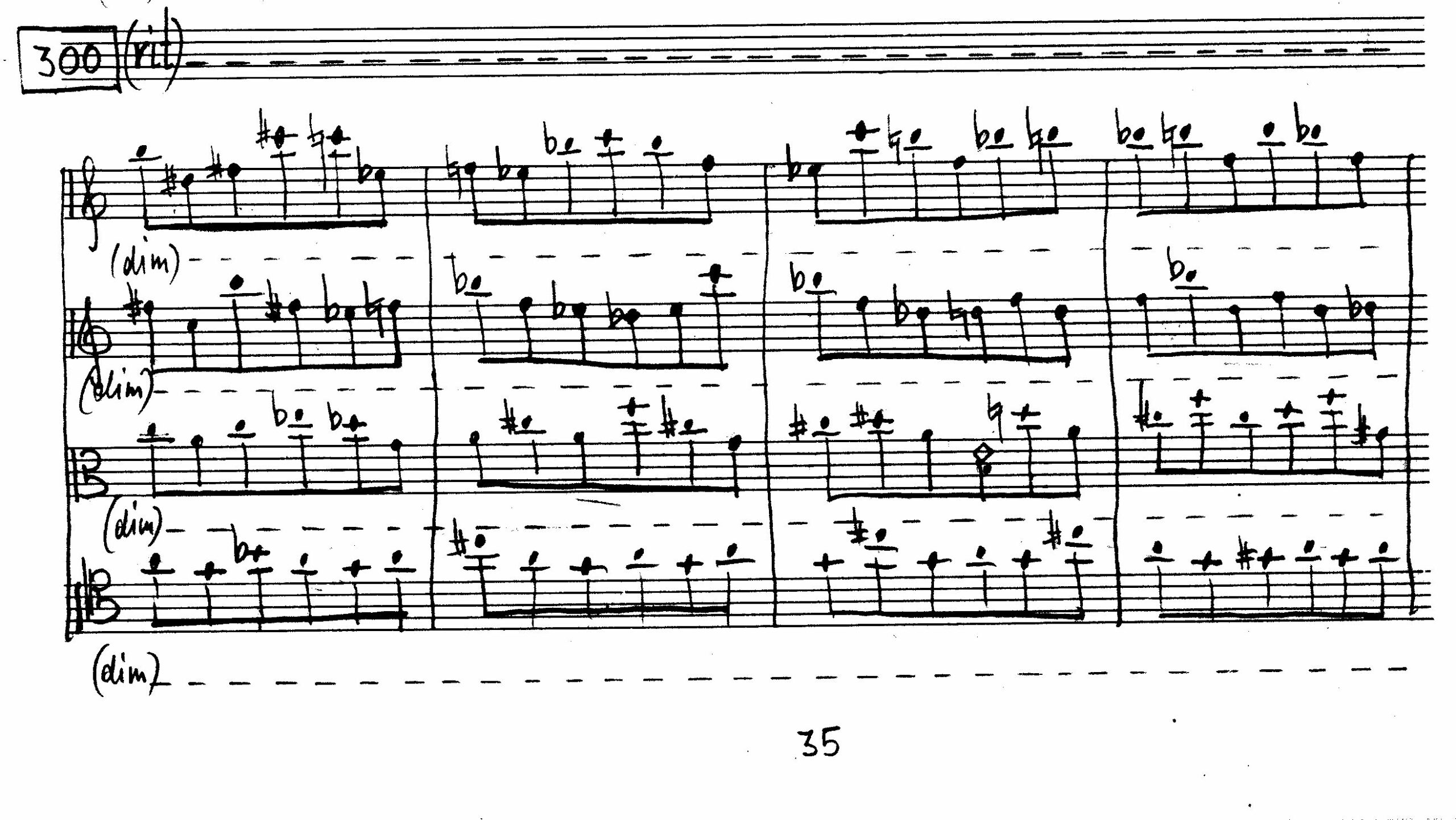

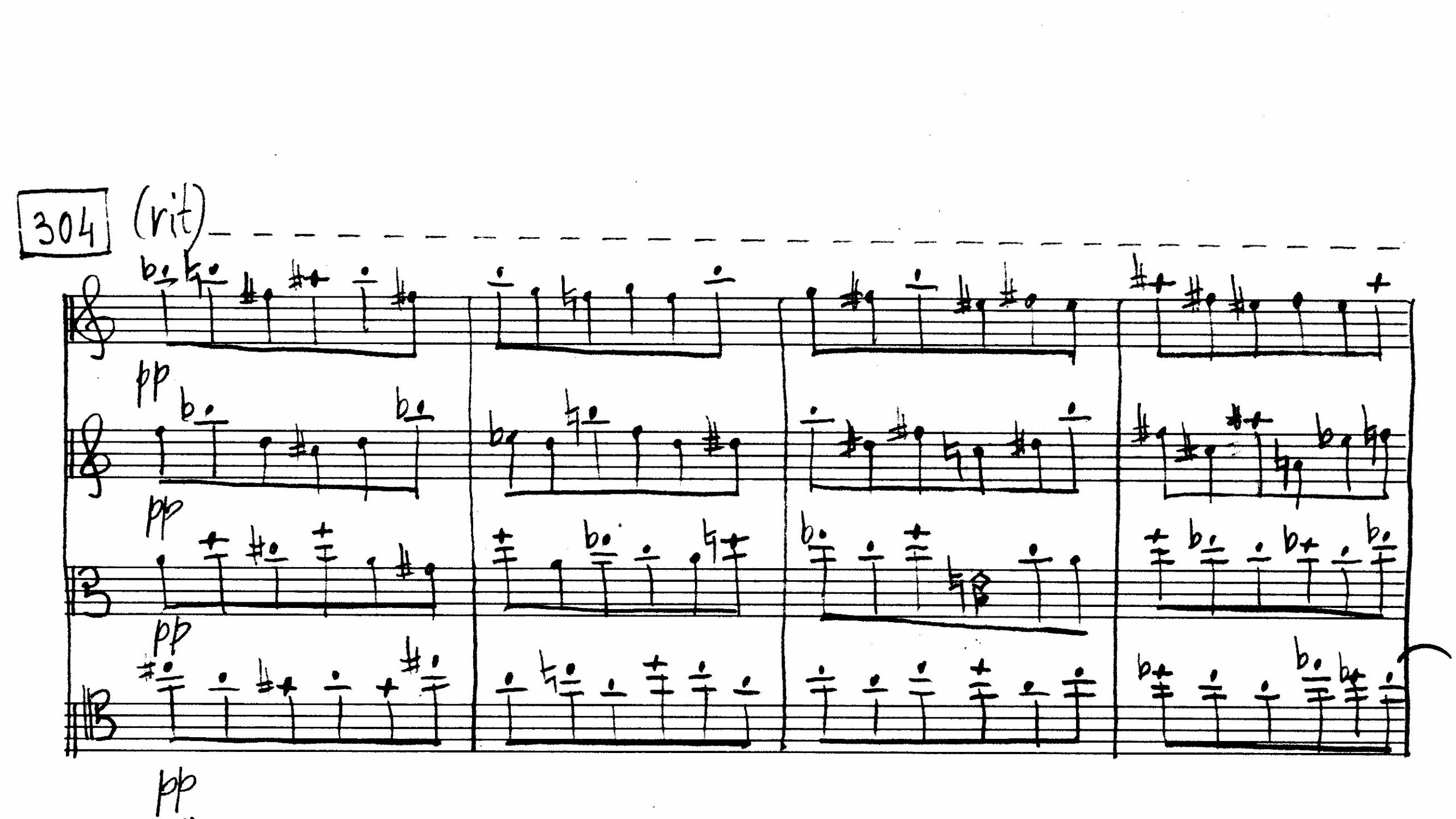

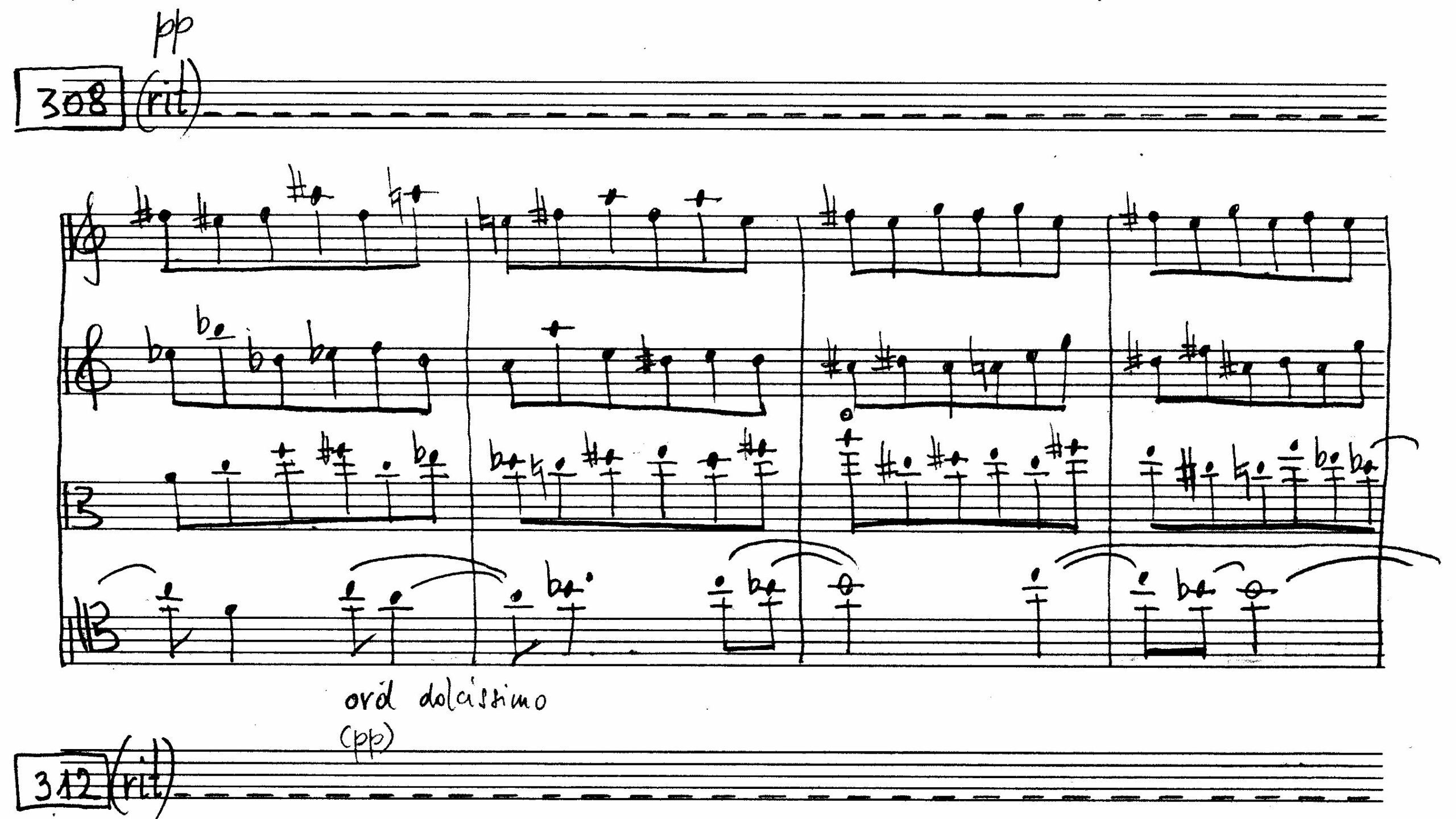

Cerha, 2. Streichquartett, T. 292-315

About the music

The contrast between disparate and uniform gestures provides the tension necessary to sustain the dramatic arc. While individual melodic formulas shape many transitions and stations, the main pillars of the work trend towards unity. This unity, however, can only be achieved through a process. For example, the polygestive ribbon of sound of the fourth station gradually dissolves when, one after the other, all the voices adopt the same type of movement as the viola (steady eighth notes)—a chameleon-like change from colourful to monochromatic. Once this new unity is established, a sense of calm arrives. “Flautando”, (flute-like) writes Cerha as an instruction for all instruments, ensuring a similar sound. And now the tempo and volume also become more uniform, until a barely perceptible threshold is reached. From this point on, the (still shimmering) acoustic activity finally begins to still. The cello is the first to detach itself from the fabric, ending in long notes. This becomes an exemplar for the other voices.

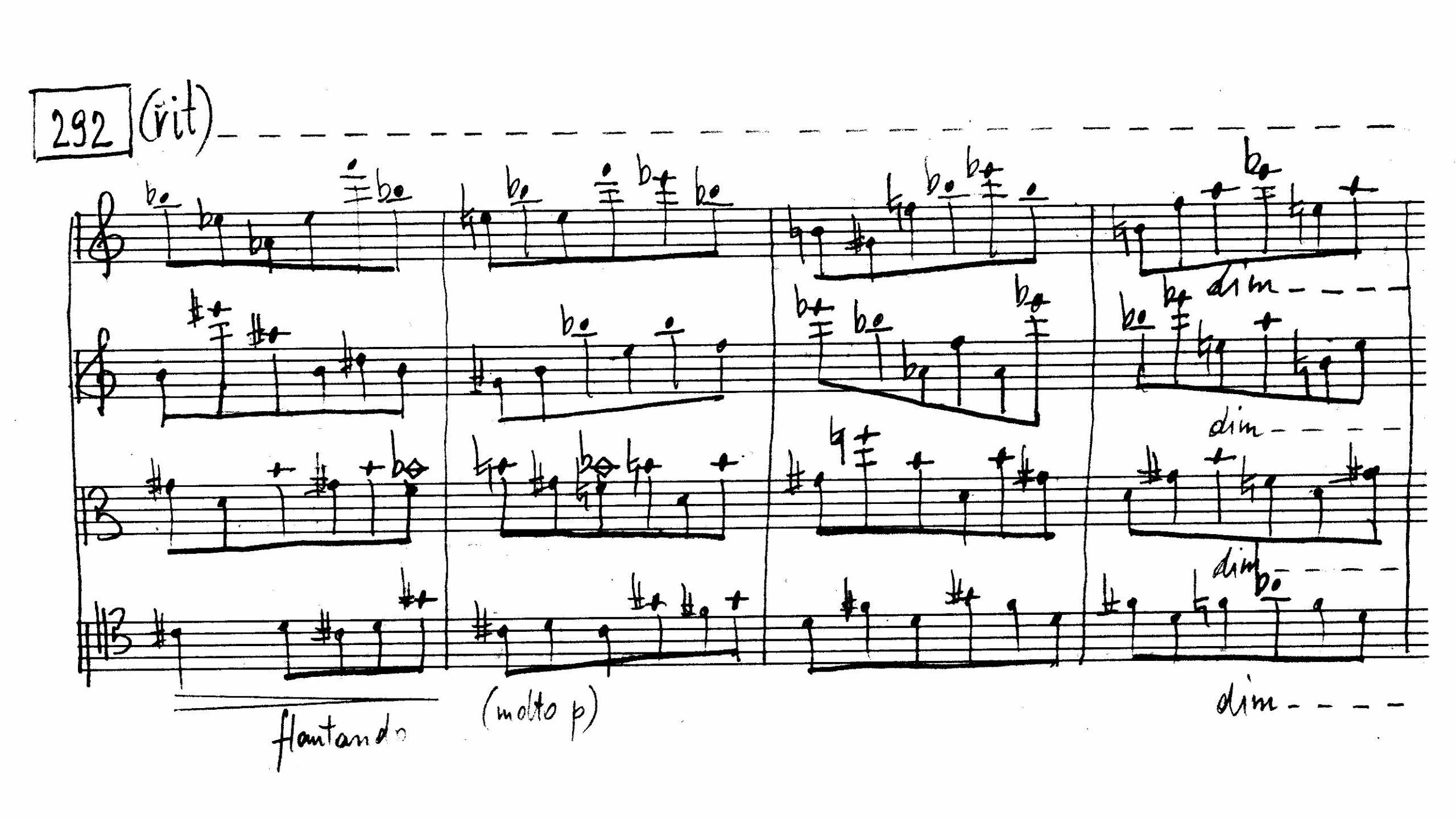

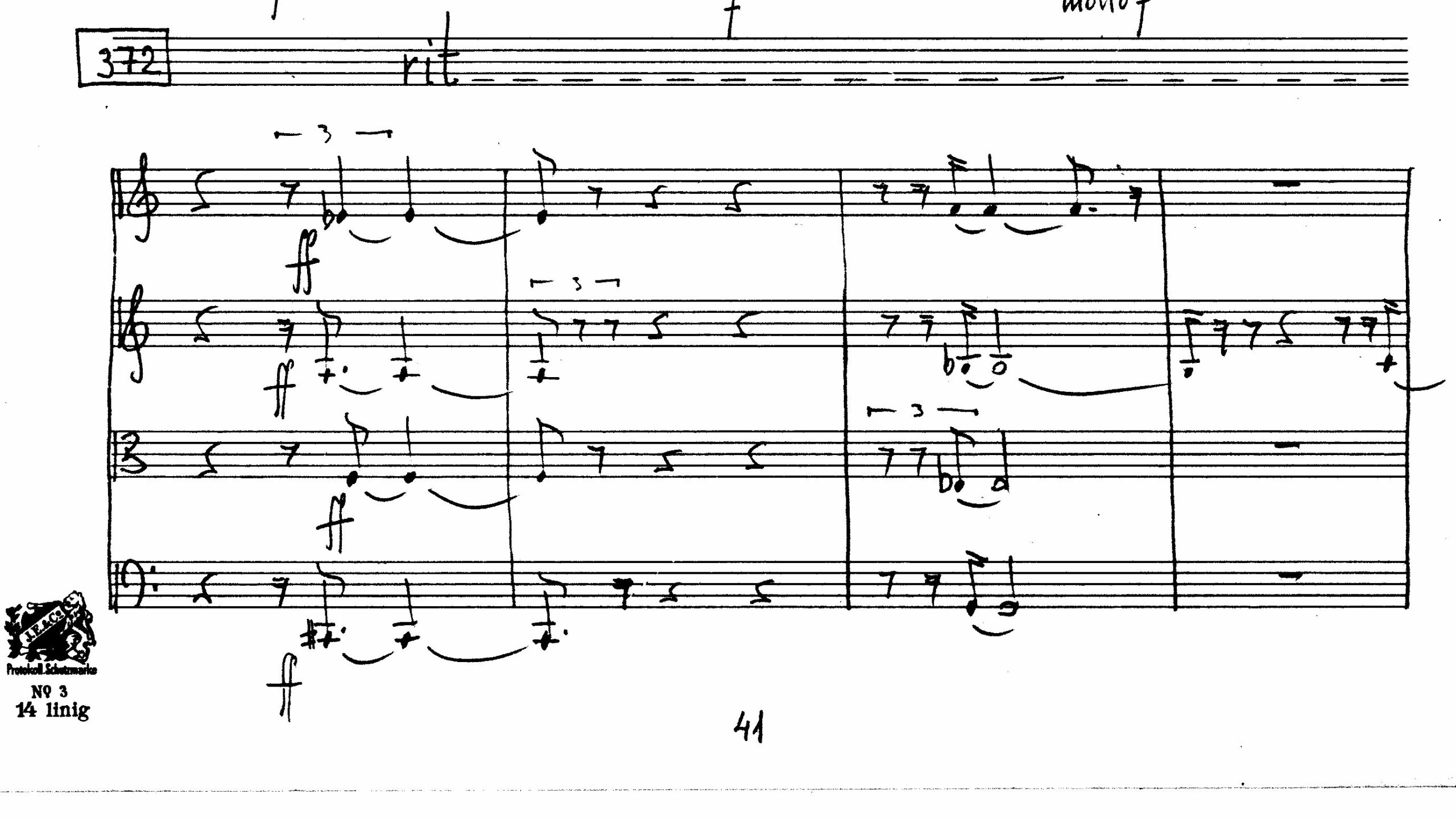

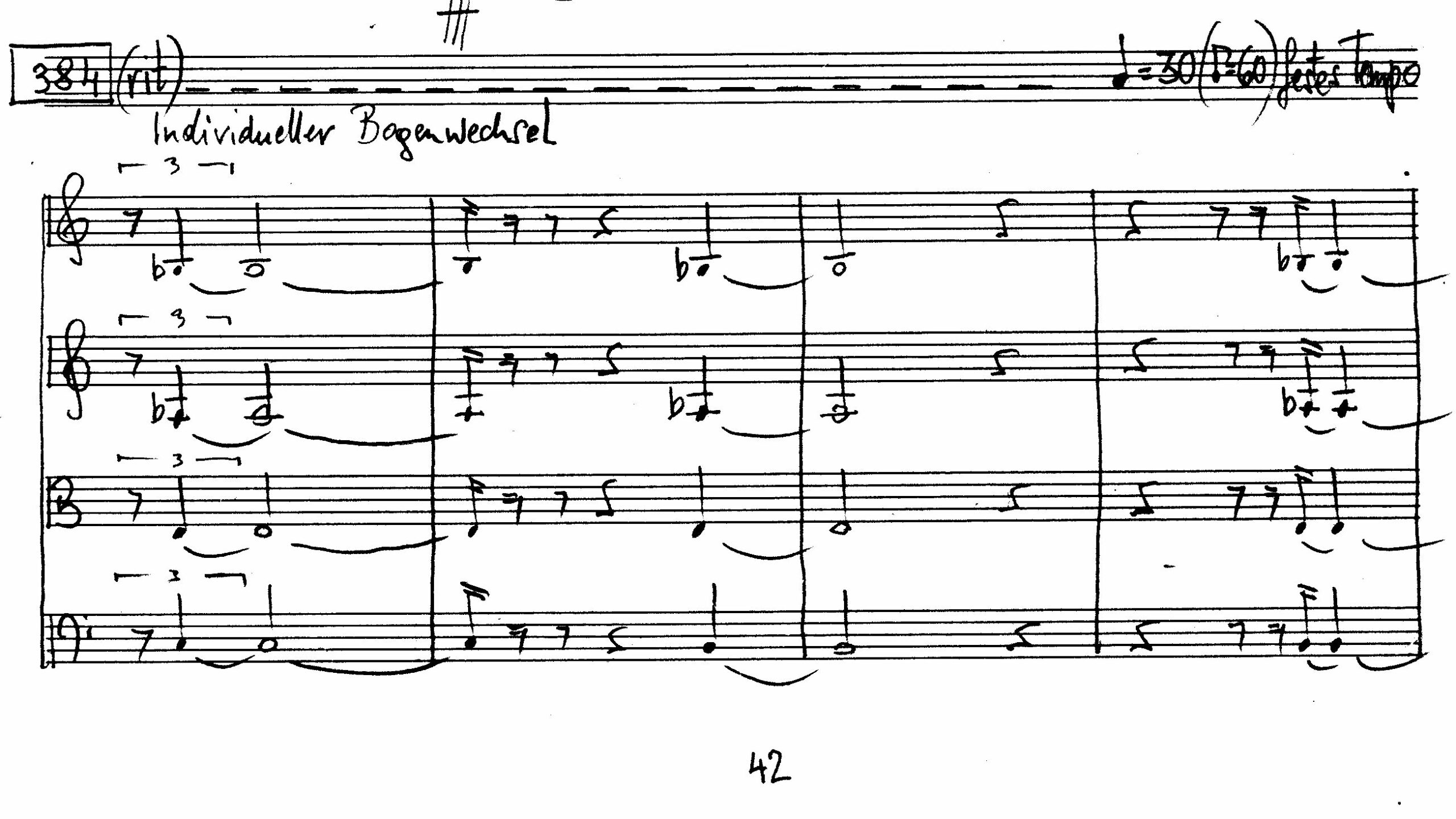

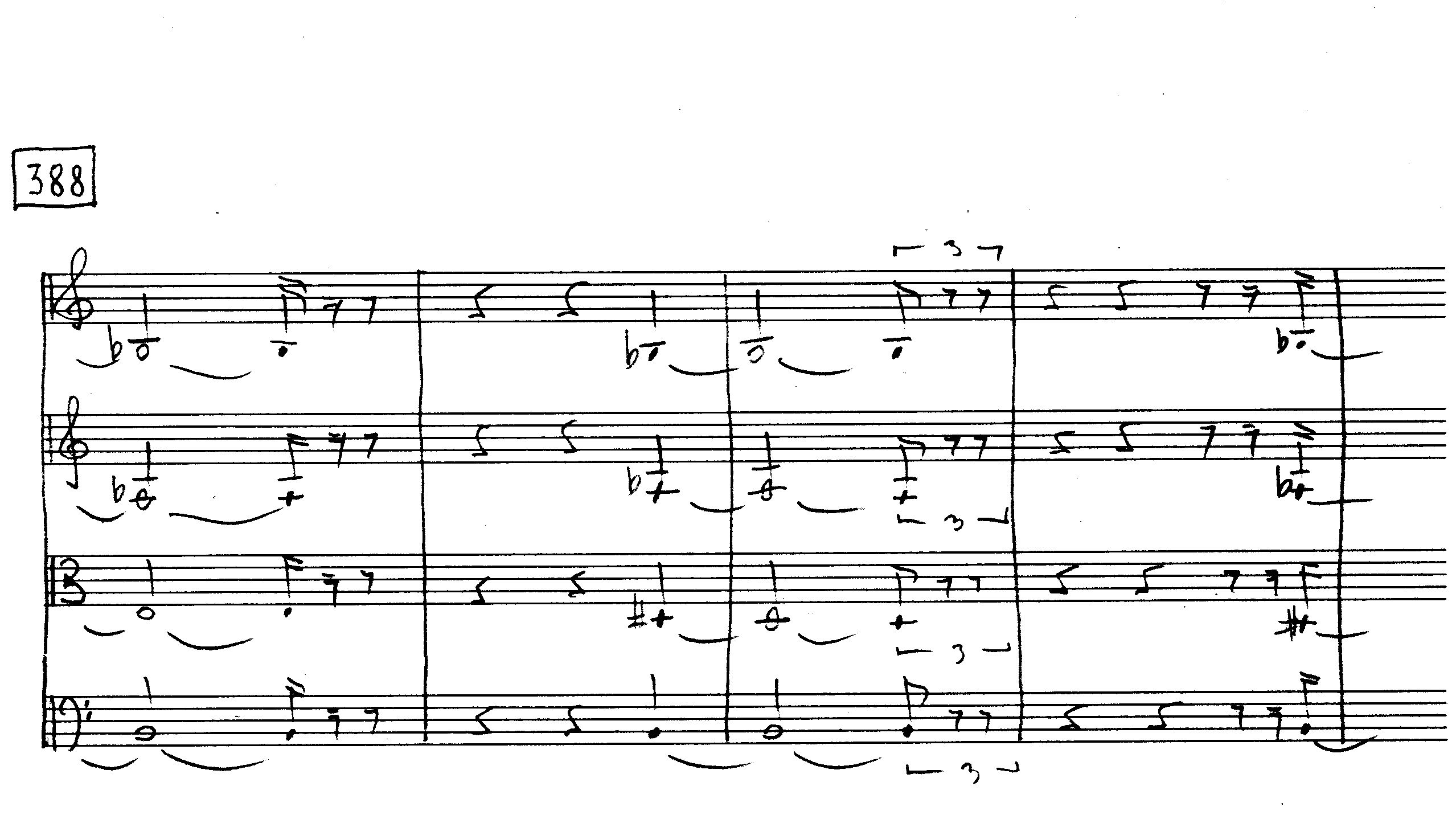

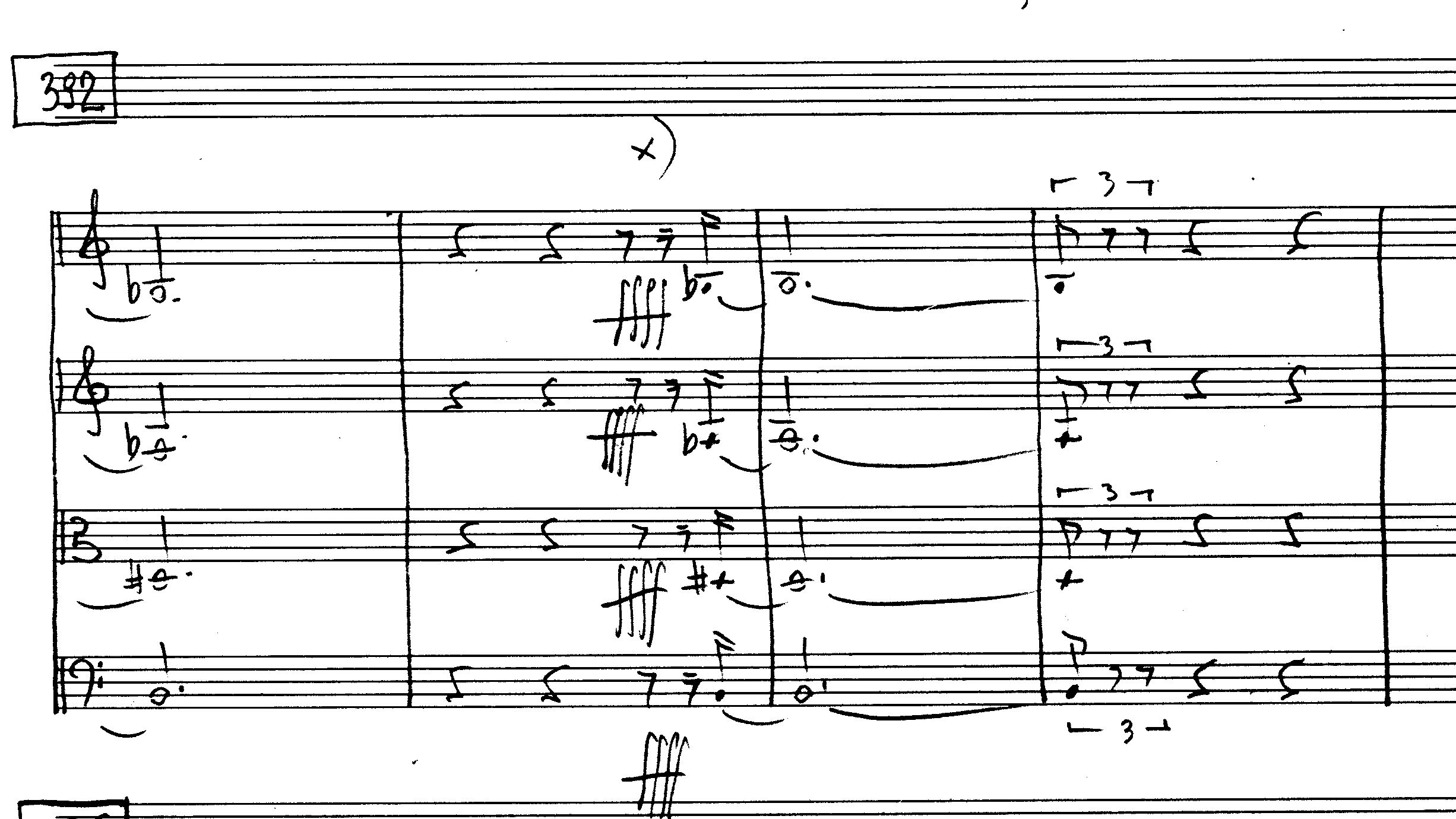

Station No. 6: Rigidity

Cerha, 2. Streichquartett, T. 364-405

About the music

Contrary to expectation, the music does not circle back to its original delicate state; instead, the finale is unrelenting. At first, all four strings go their individual ways, although the paths often consist only of single long notes. Like lone elements in search of one another, the isolated tones finally shift to join together. Now, as a result of this merging process, only single chords exist, limiting change to just a few spots—for example, by exchanging individual notes. There is an inevitability to the approaching rigidity, its call louder and louder, pushing the limits of possibility. In the final bars, all change is eliminated. There is only the plonk of one petrified chord block after the other, with chunks of silence to fill the tense musical space in between. Filled with fear, the piece ends in the musical shadow of dark and powerful monoliths.