I. Keintate

A leich aum otagringa friidhof

Langegger Nachtmusik I

Gschwandtner Tänze

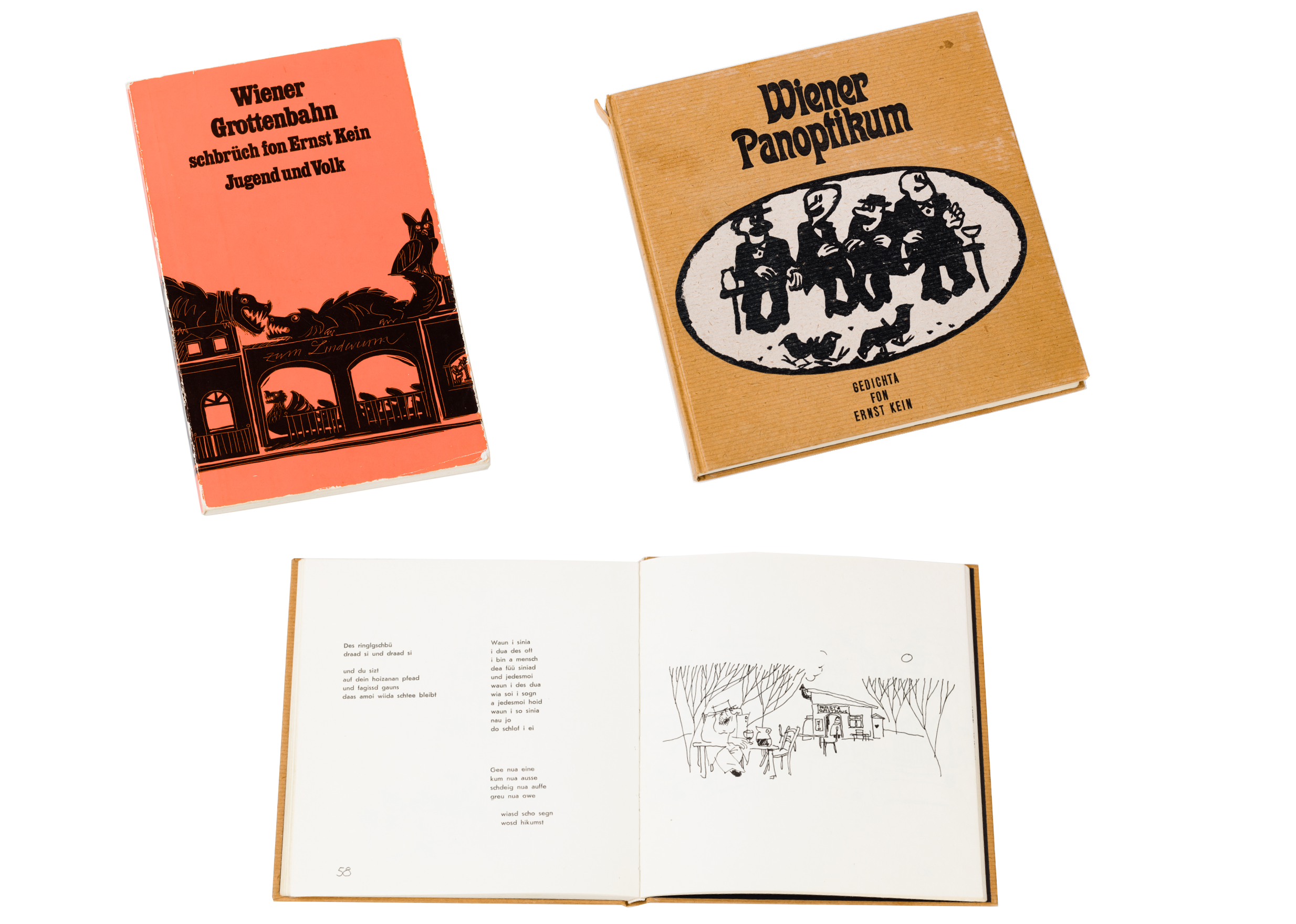

Ernst Kein, Wiener Panoptikum, cover

In 1970, Ernst Kein published a collection of poems in Austrian dialect titled Wiener Panoptikum. For the cover, Jörg Hornberger sketched four older men sitting on a park bench feeding pigeons. One of the poems features a humorous take on the annoying excretions of this type of urban wildlife.

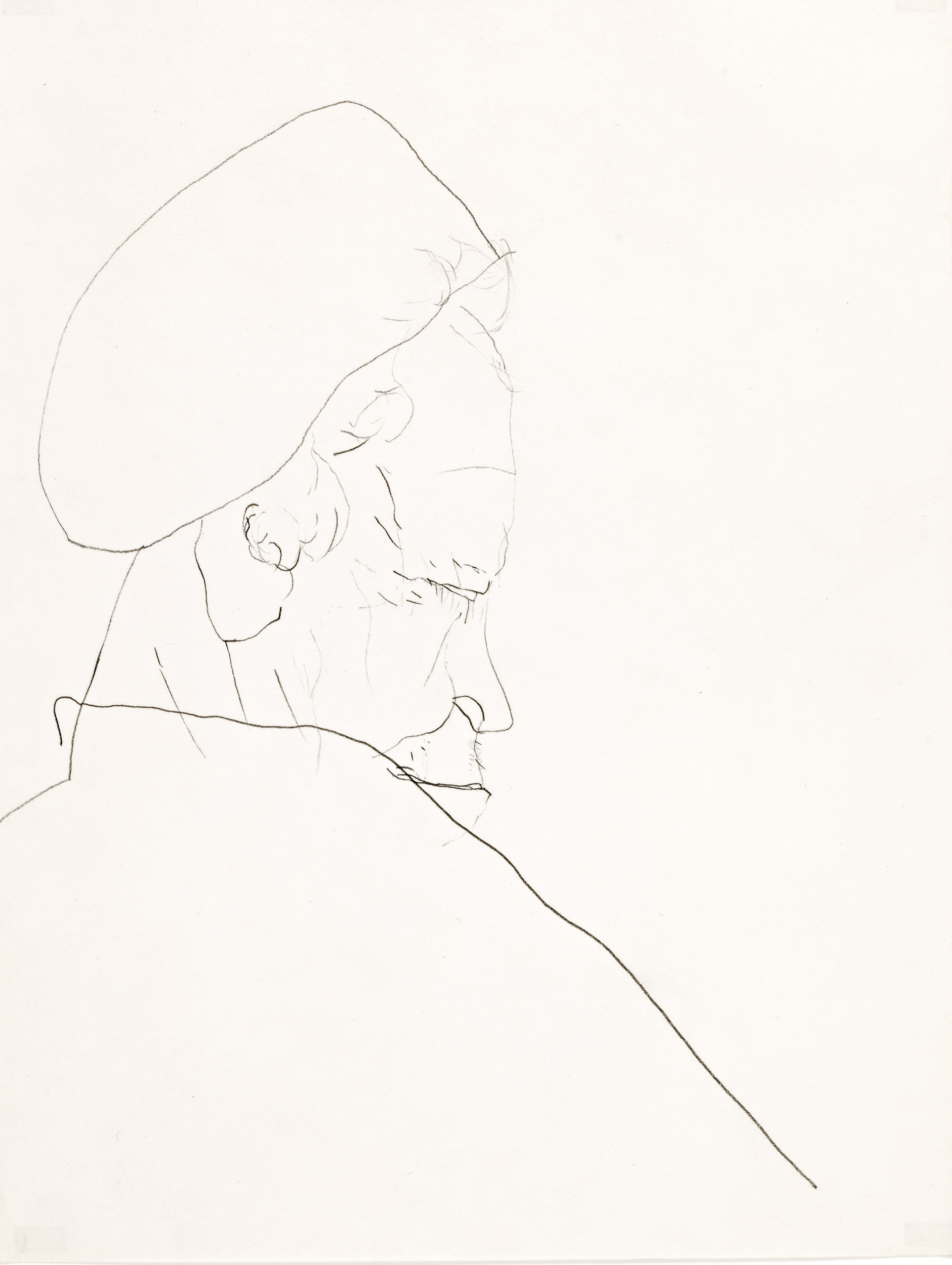

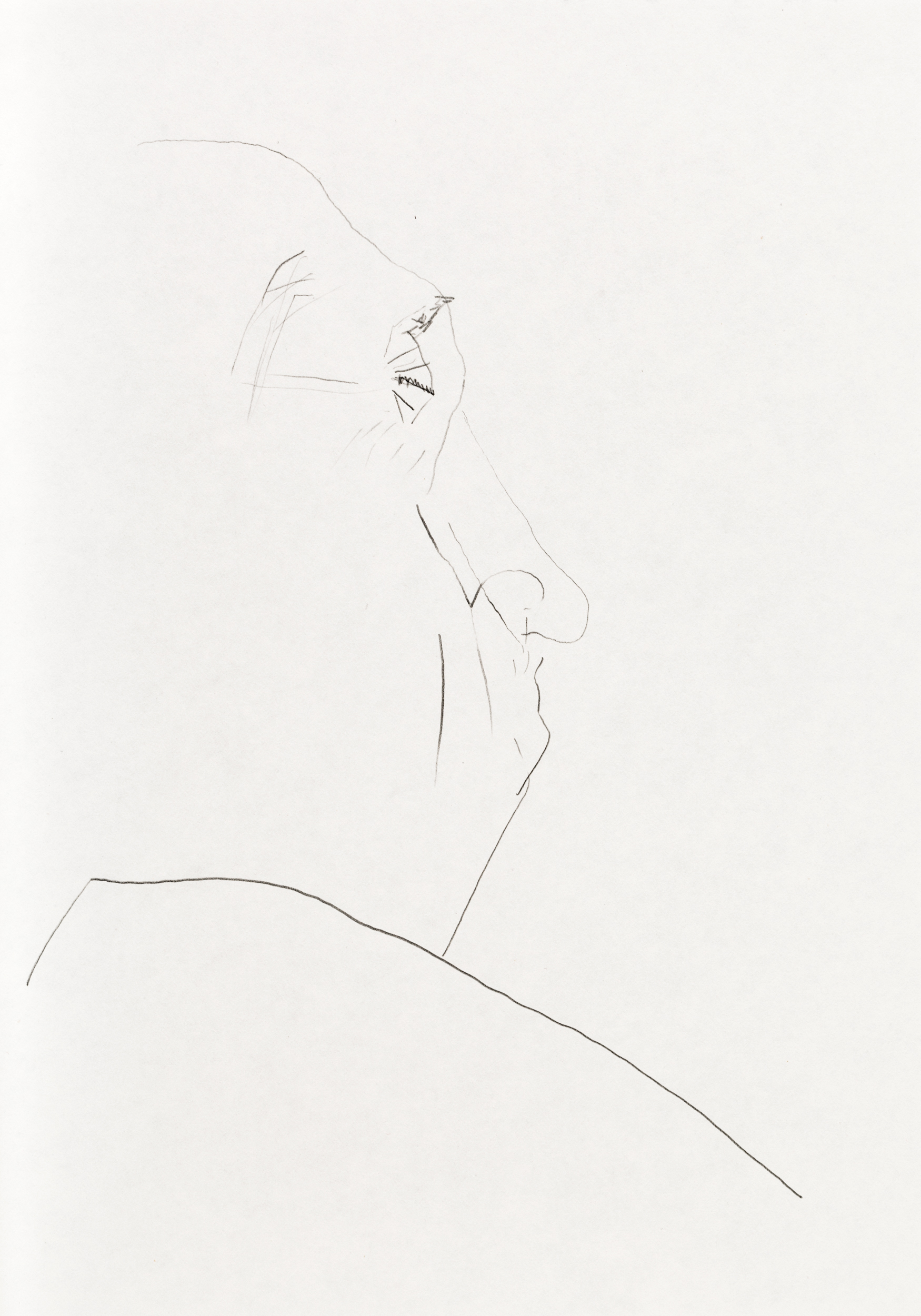

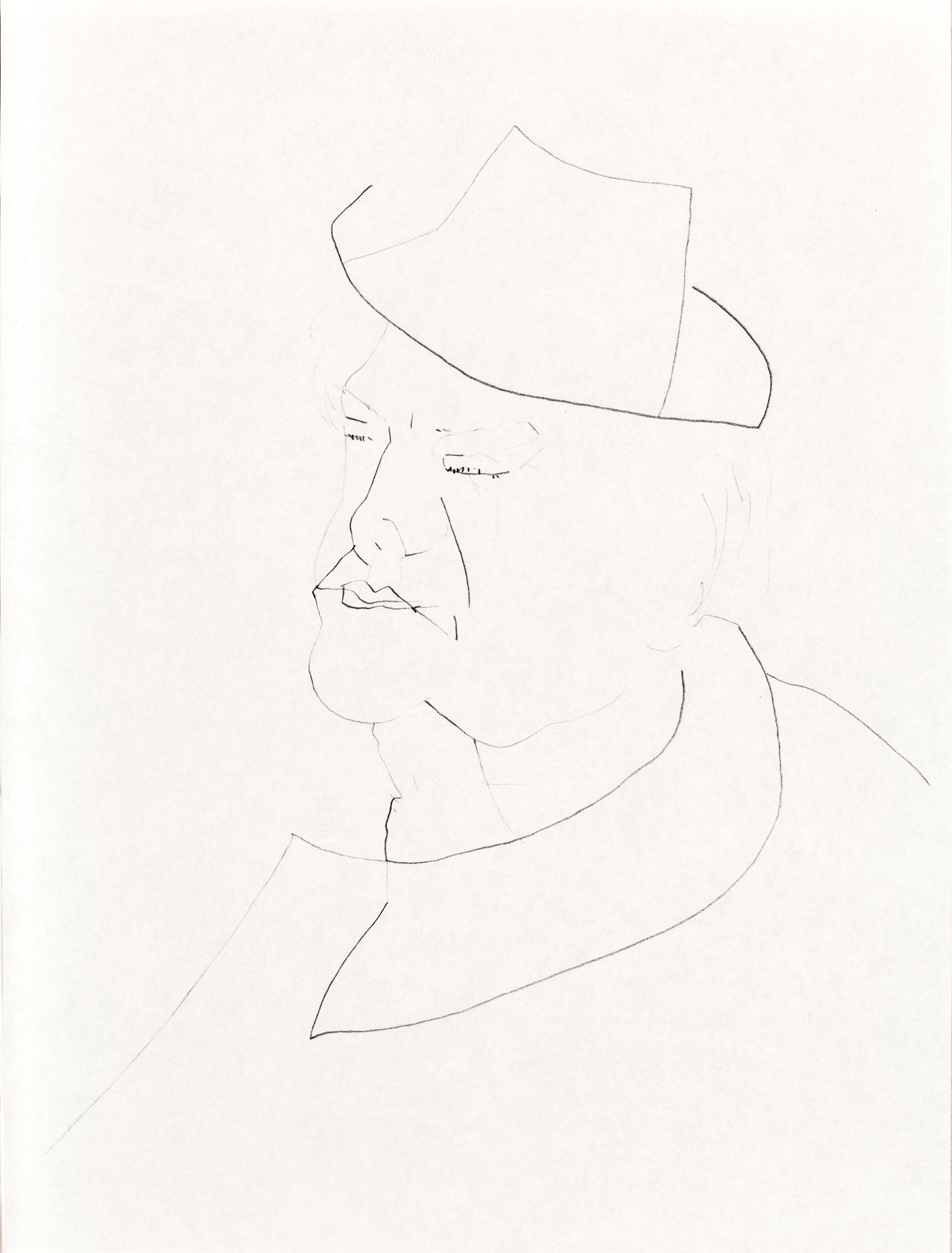

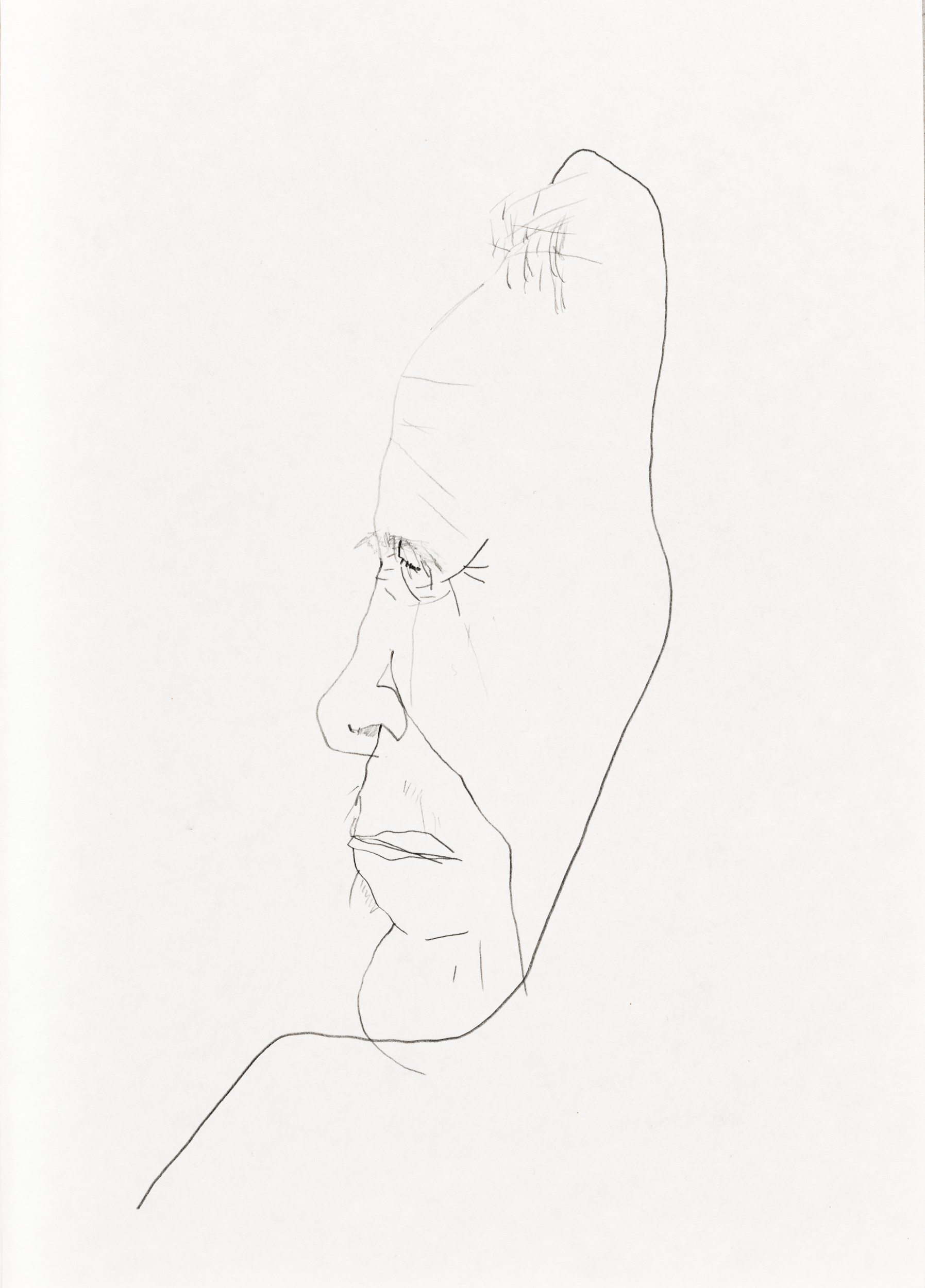

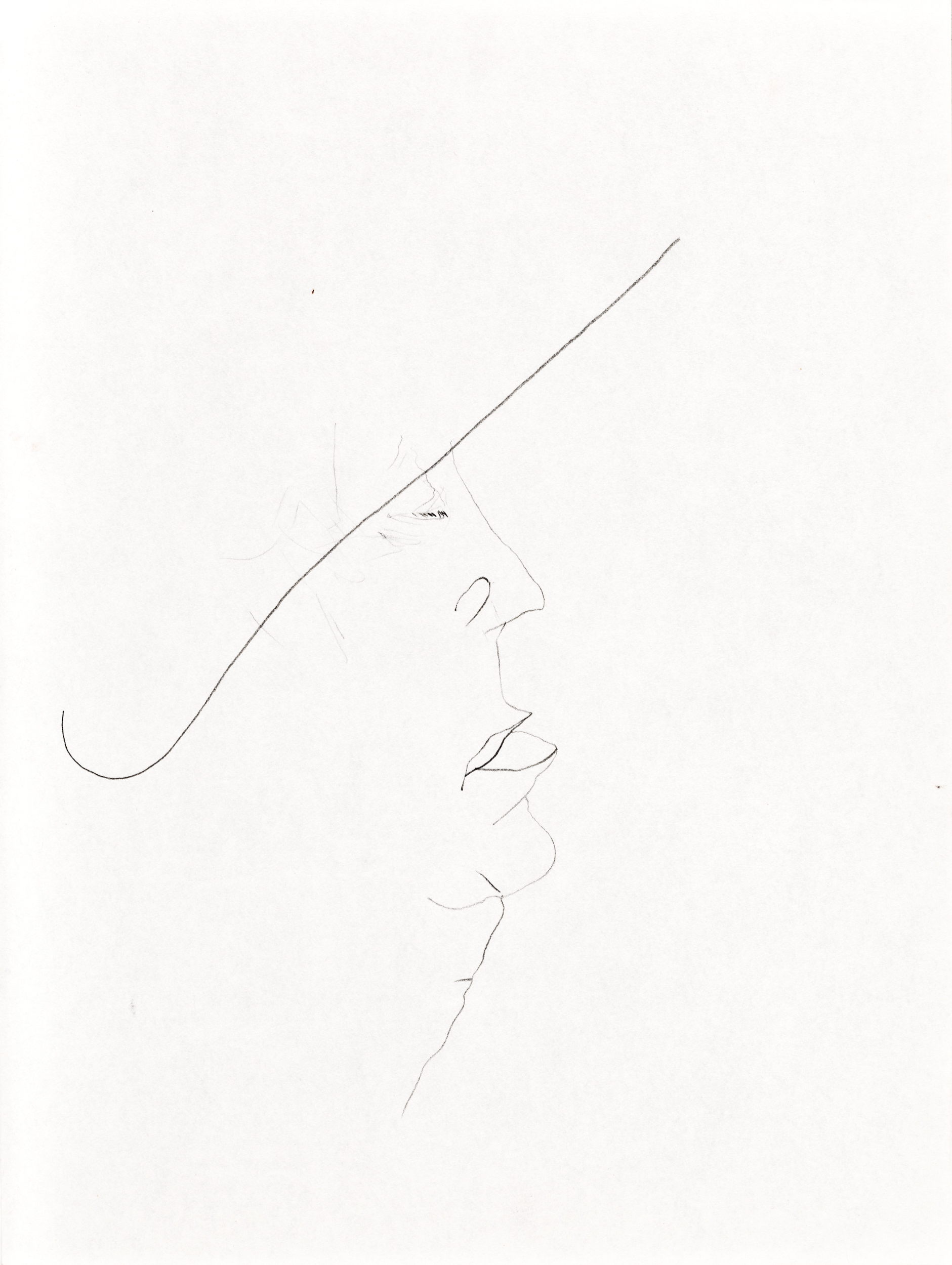

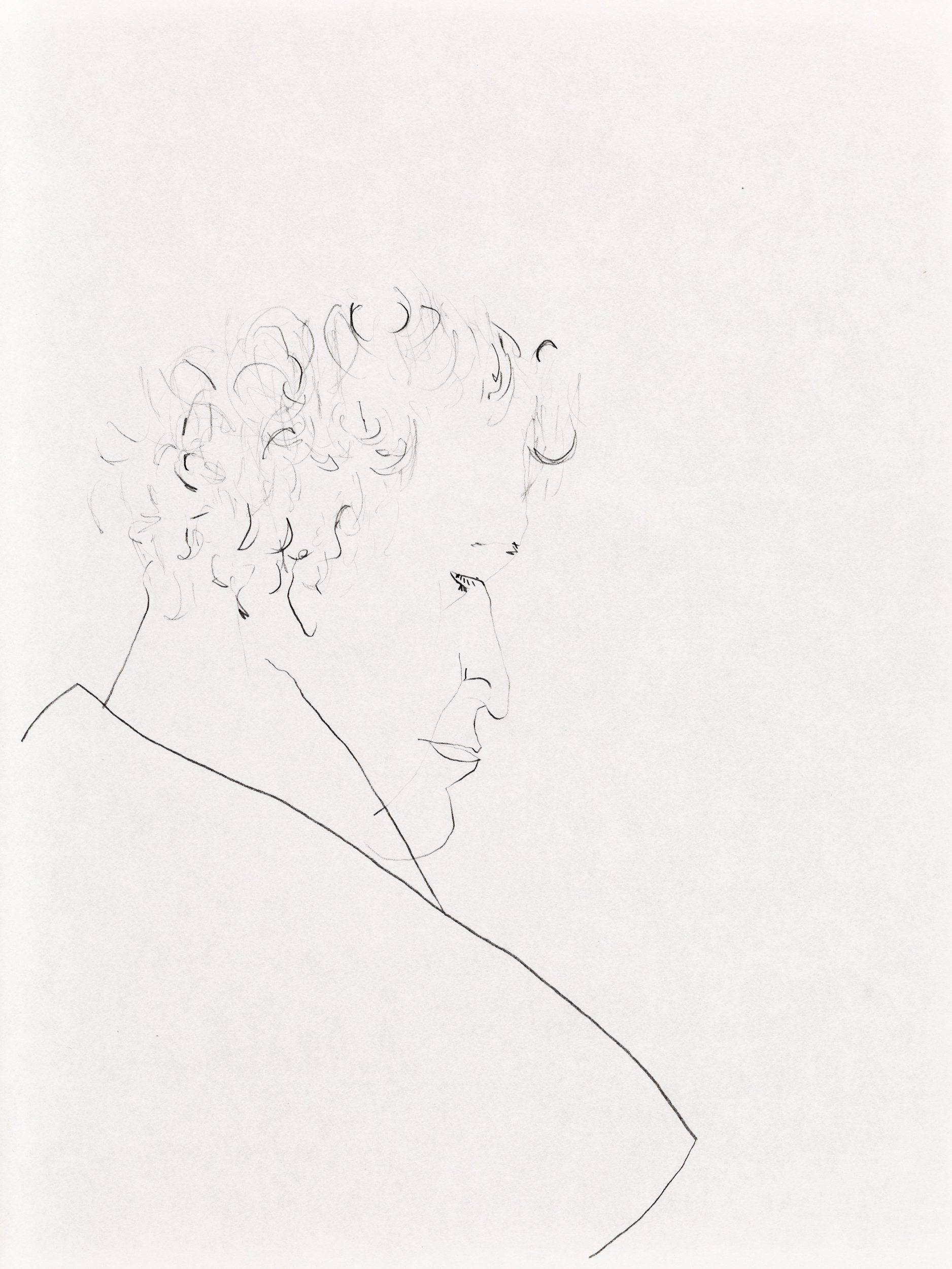

Friedrich Cerha’s Keintaten revolve around “Viennese types”—

as does a series of drawings by his daughter Irina.

Foto: Christoph Fuchs

The character studies capture the stubbornness of Viennese society very well, revealing characteristics like arrogance, reserve, and scepticism, but also grace, wisdom, and humour. The eccentric portraits were sketched in the early 1980s, a time when Friedrich Cerha was tackling a project that was related in spirit, his I. Keintate (a second Keintate was written a little later). It made sense to combine the music and the drawings, which was the beginning of the piece’s long history of mixing media. On the day of the premiere, 19 June 1983, Irina Cerha’s series of sketches was also exhibited. The soundscape that surrounded the Viennese audience that evening offered surprises: The music was entertaining in a way that many would not have expected from Cerha.

Außenansicht

In the time that passed between Vergnügliche Musik and the first Keintate (composed 1980–1982), Cerha’s path to his own roots took rambling diversions. After coming into contact with the international avant-garde, he wound his way back to an increasingly traditional musical language—which in turn paved the way to Keintate. However, the path was by no means straightforward. One of the most formative “detours” was Cerha’s interest in non-European musical culture, which began early in comparison to when it bore compositional fruit, in around 1990. However, it was only through this gazing into the distance that his interest in the nearby, in his own cultural region, was renewed. The discovery of the unknown led to the rediscovery of the known, Viennese folk music, which Cerha had had in his blood “since childhood”Thomas Meyer, interview with Friedrich Cerha, February 2012, https://www.evs-musikstiftung.ch/de/preise/preise/archiv/hauptpreistraeger/friedrich-cerha/interview.html, but as a composer had “completely ignored” for years.

For a long time, it was important for me to see myself as a citizen of the world, and I also saw myself as making music that fit this view. It actually took me a long time to realize that this was not true and that there are roots right here that I had not seen or, if I had seen them, may not have wanted to really internalise them, as is true of so many of my generation. It has always been one of my principles to examine things carefully, to not let them go unchecked, when I notice a certain phenomenon or tendency. And this is the path that brought me back to my own past, so to speak.

Friedrich Cerha

Thomas Meyer, interview with Friedrich Cerha, February 2012, https://www.evs-musikstiftung.ch/de/preise/preise/archiv/hauptpreistraeger/friedrich-cerha/interview.html

Brücke

Deceptive harmlessness and the concealment of bitter evil are also themes in Cerha’s Keintate. The word Keintate is blended from the German word Keintate (cantata), something to sing, and the name of the poet Ernst Kein.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 246 Although it was H. C. Artmann who hugely boosted the popularity of Viennese dialect poetry by publishing his volume med ana schwoazzn dintn in 1958, Ernst Kein was already writing in a similar fashion in 1954. He became known to a wide public through his columns in the Austrian daily newspaper Kronen Zeitung under the pseudonyms “Herr Strudl” and “Herr Habe”.

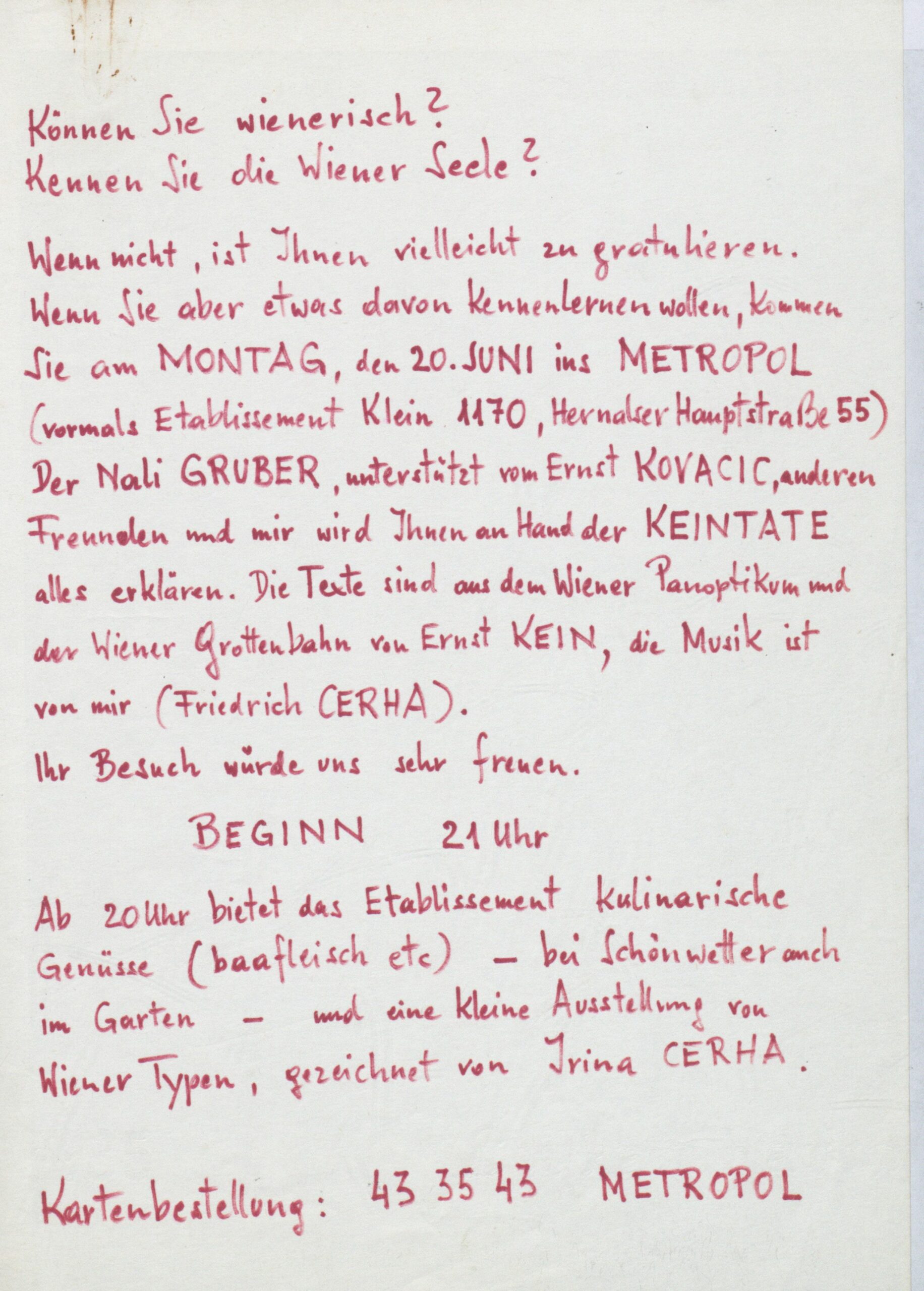

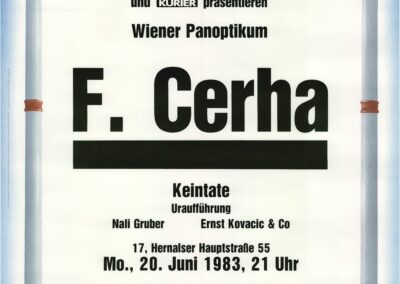

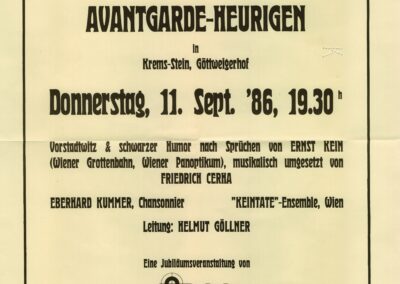

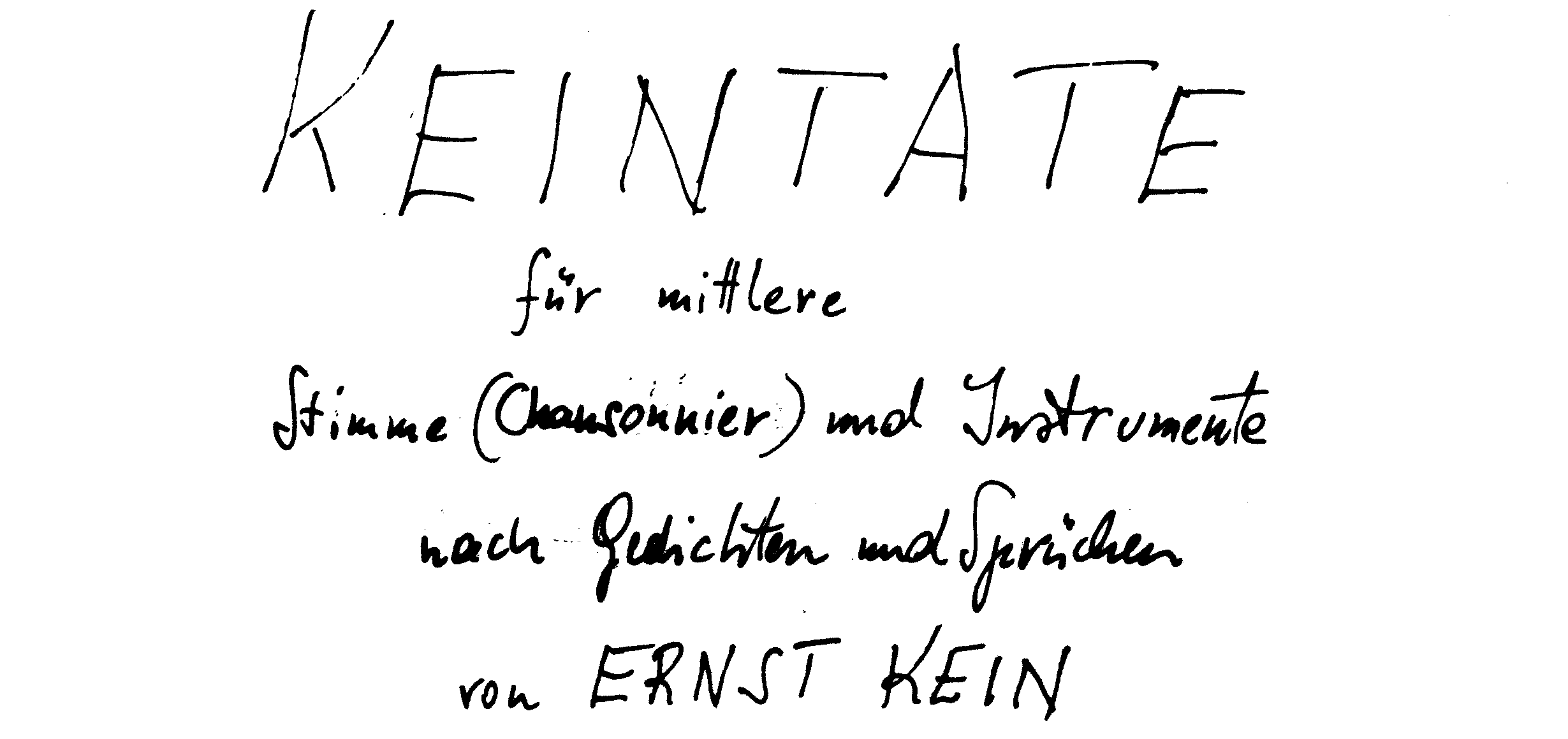

Cerha’s Keintate uses two sources from his poet friend: Wiener Panopticon (1970) and Wiener Grottenbahn (1972). Cerha combined selected texts from these two volumes of poetry into a libretto with its own dramaturgy. The work was premiered on 20 June 1983—naturally by Cerha, Gruber, and “friends”, according to the announcement (including Ernst Kovacic on the first violin). Contrary to the custom of performing in a concert hall, the musicians chose an unusual location for the premiere: the Metropol in the 17th district of Hernals, a place deliberately close to the people. A self-made, handwritten poster by the composer, inviting listeners to the Metropol concert, speaks volumes:

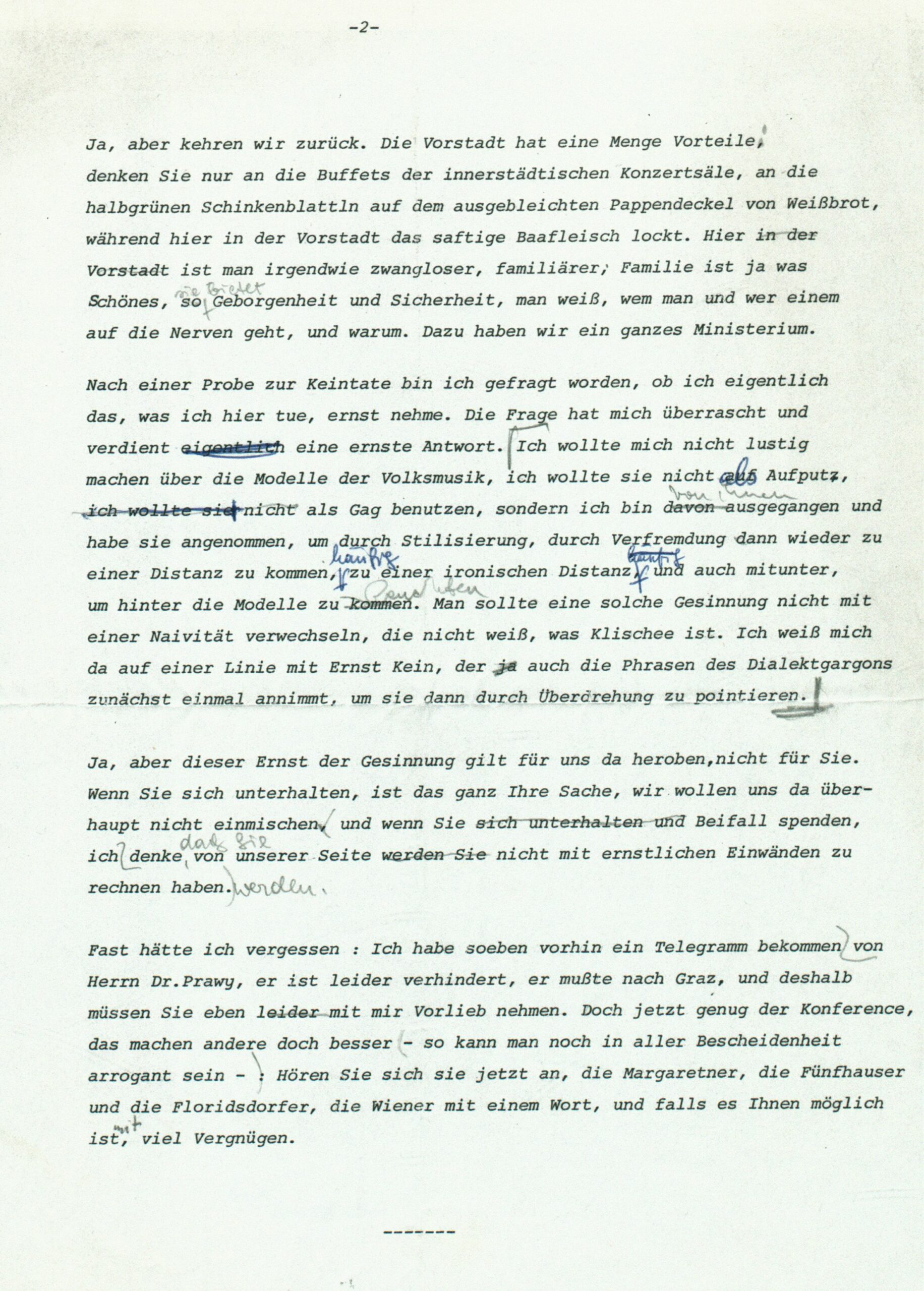

Cerha, “impromptu speech” at the premiere of I. Keintate, manuscript, 1983

Cerha, Stegreif-Rede, Metropol Wien, 20.6.1983

A clear reference to the Viennese popular music so familiar to Cerha can be seen in the instrumentation of the Keintate ensemble, made up of two clarinets and two horns, a button accordion, drums, and a string quintet with double bass. These instruments evoke “musically rich associations with a ‘Heurigenpartie’ (wine tavern band)”Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 247, states Cerha. The Schrammelharmonika in particular, a forerunner of the modern accordion with a much softer sound, is strongly associated with the “typical party music”Ernst Weber, “Heurigenmusik”, in: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online heard in Vienna’s wine pubs in the mid-nineteenth century. Violins, clarinets, and post horns, often used for two parts, were also considered “permanent fixtures of the instrumentation”Ernst Weber, “Heurigenmusik”, in: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online at the end of the century. Up until the First World War, performances by these popular ensembles at Heurige and city bars shaped Viennese musical life. The “globalisation of popular music” that took place after the warErnst Weber, “Heurigenmusik”, in: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online then gradually displaced the local music styles with Schlager hits, salon music, and jazz.

Innenansicht

Ernst Kein Wiener Grottenbahn (top left) and Wiener Panopticon (top right and below),

Cerha’s private copies

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

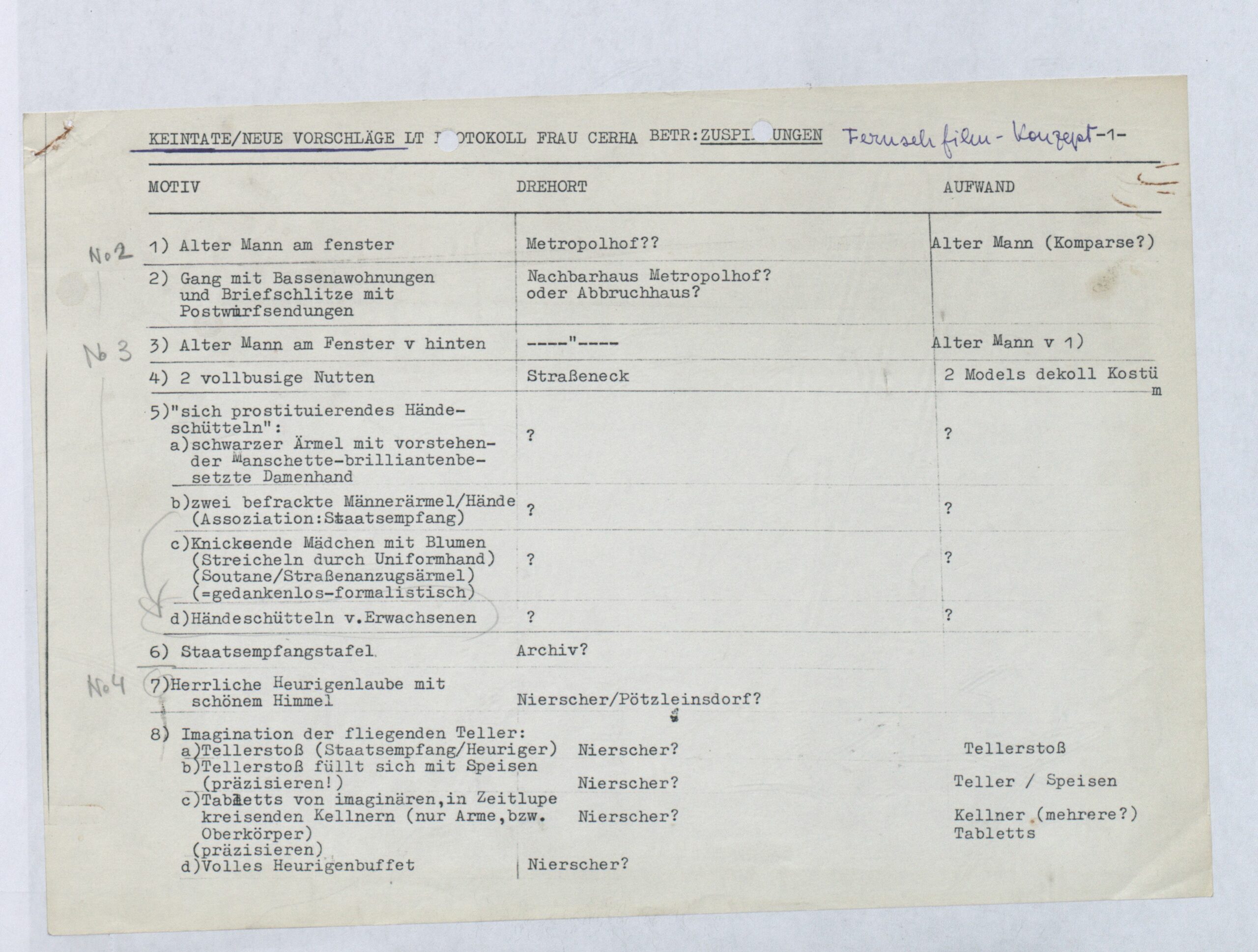

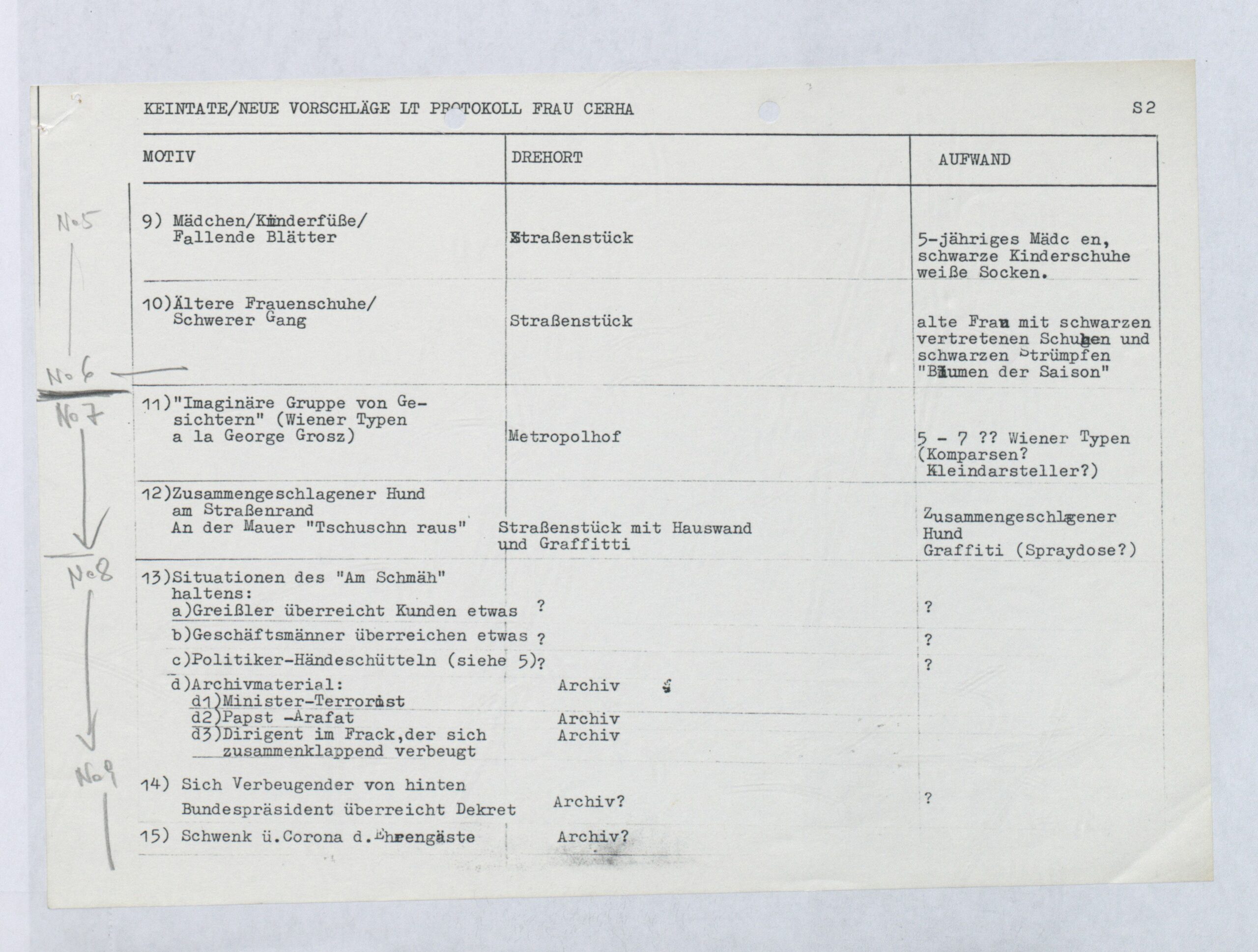

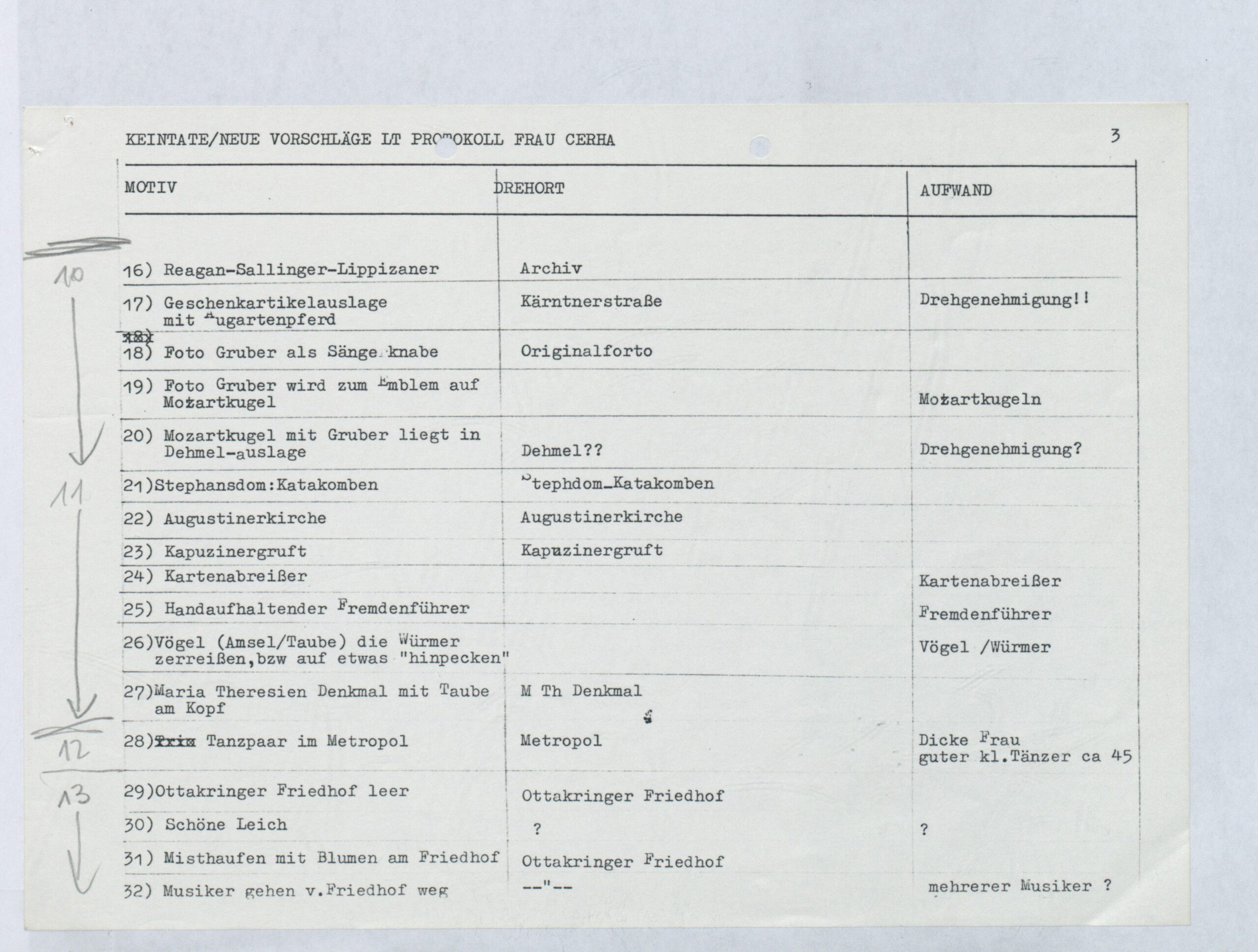

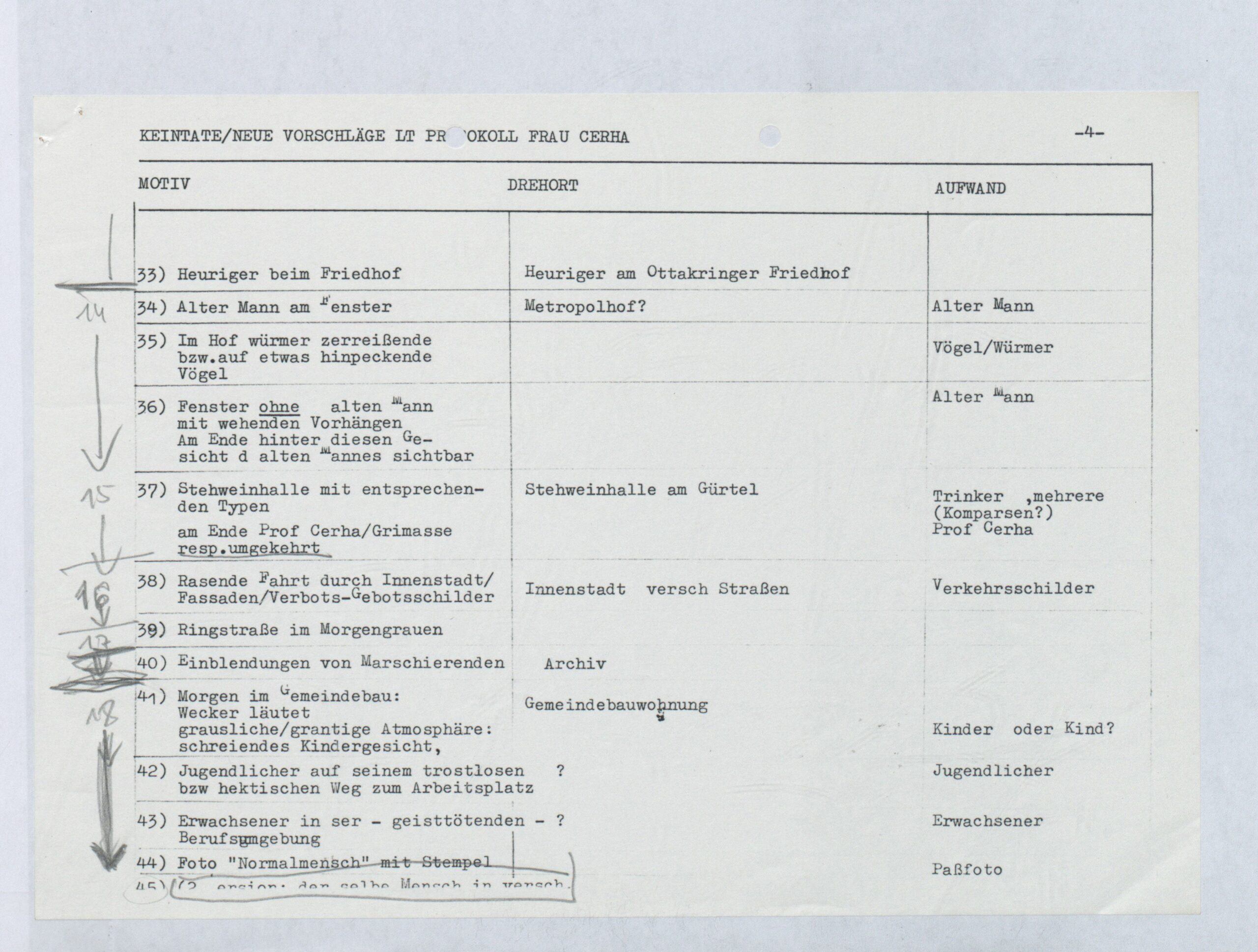

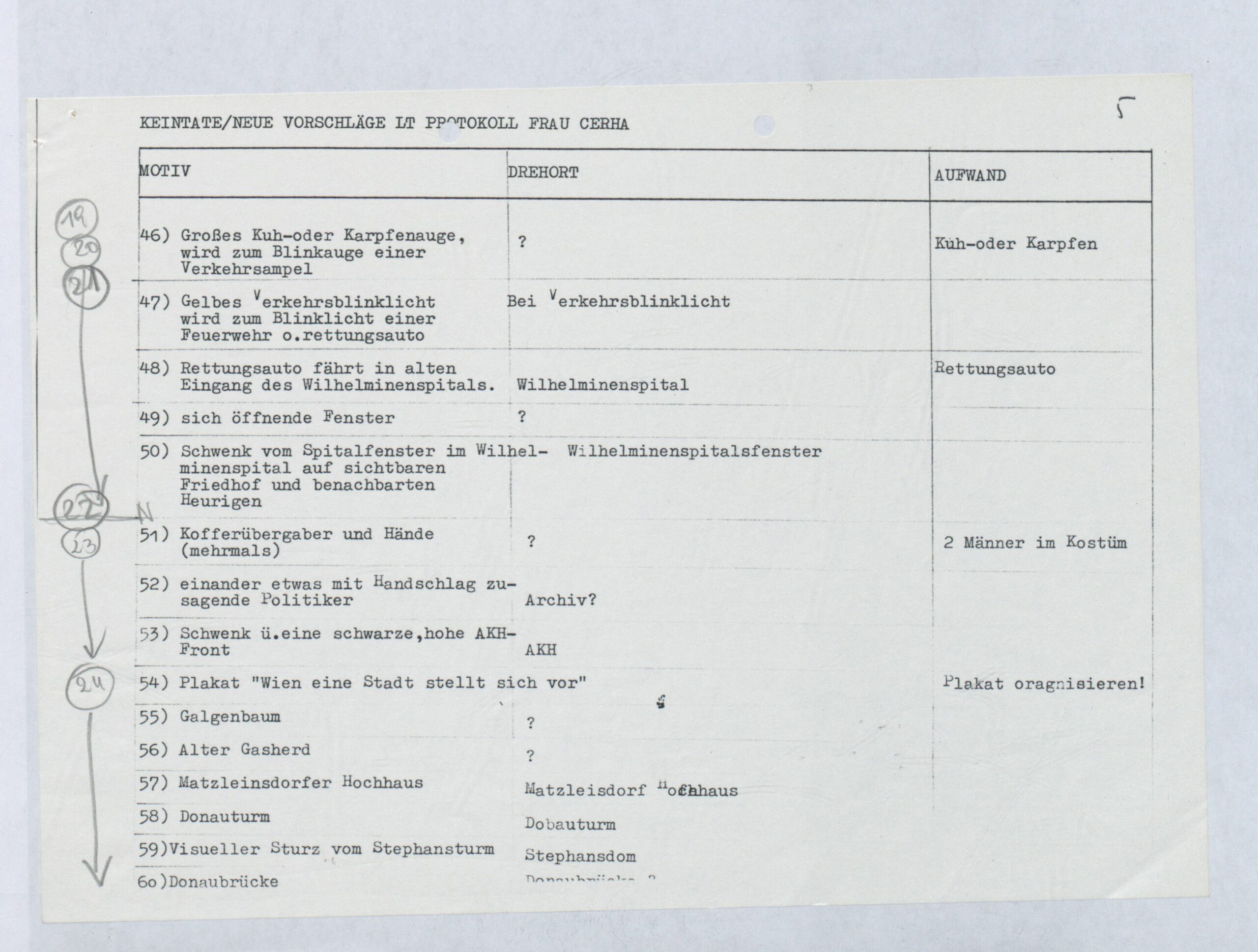

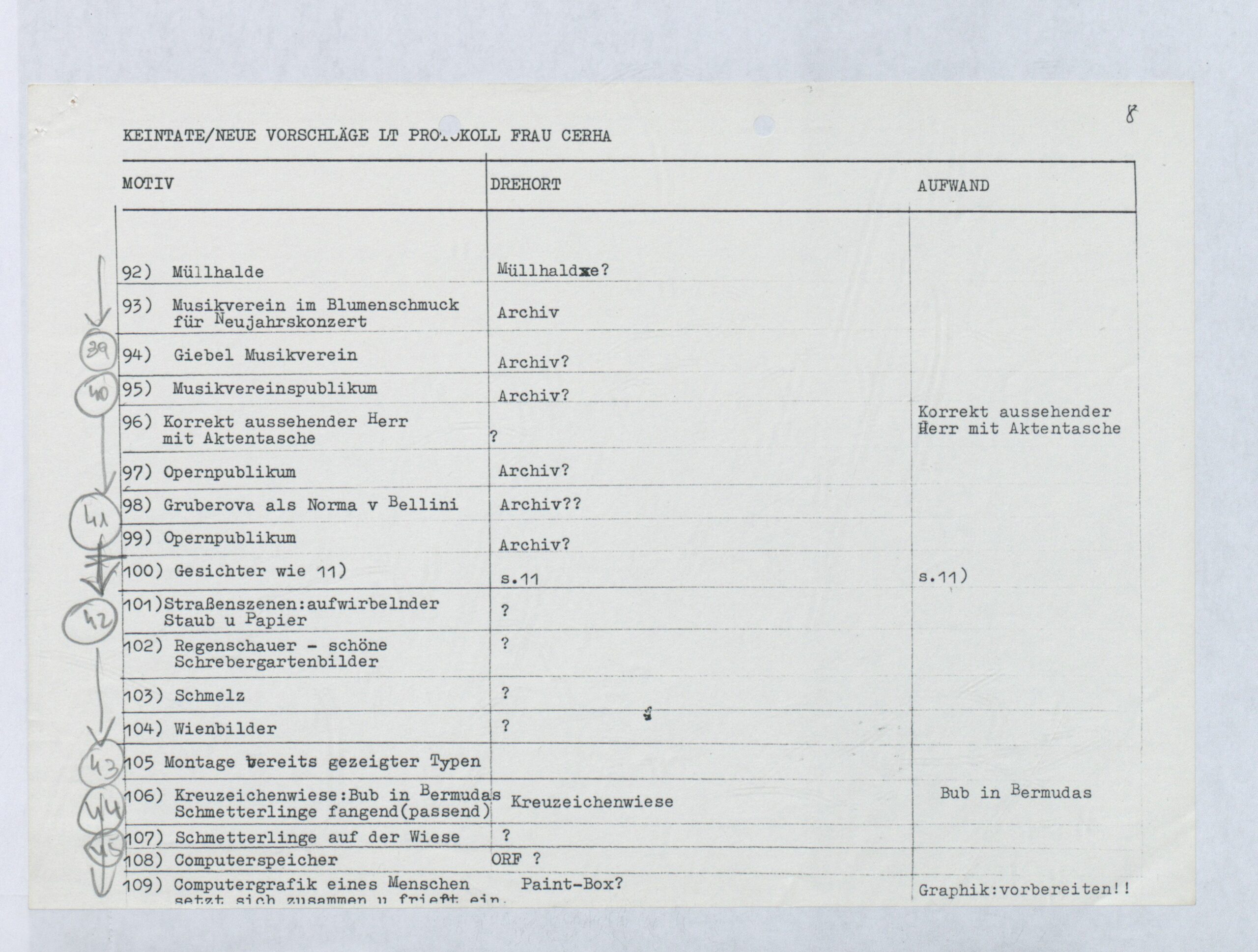

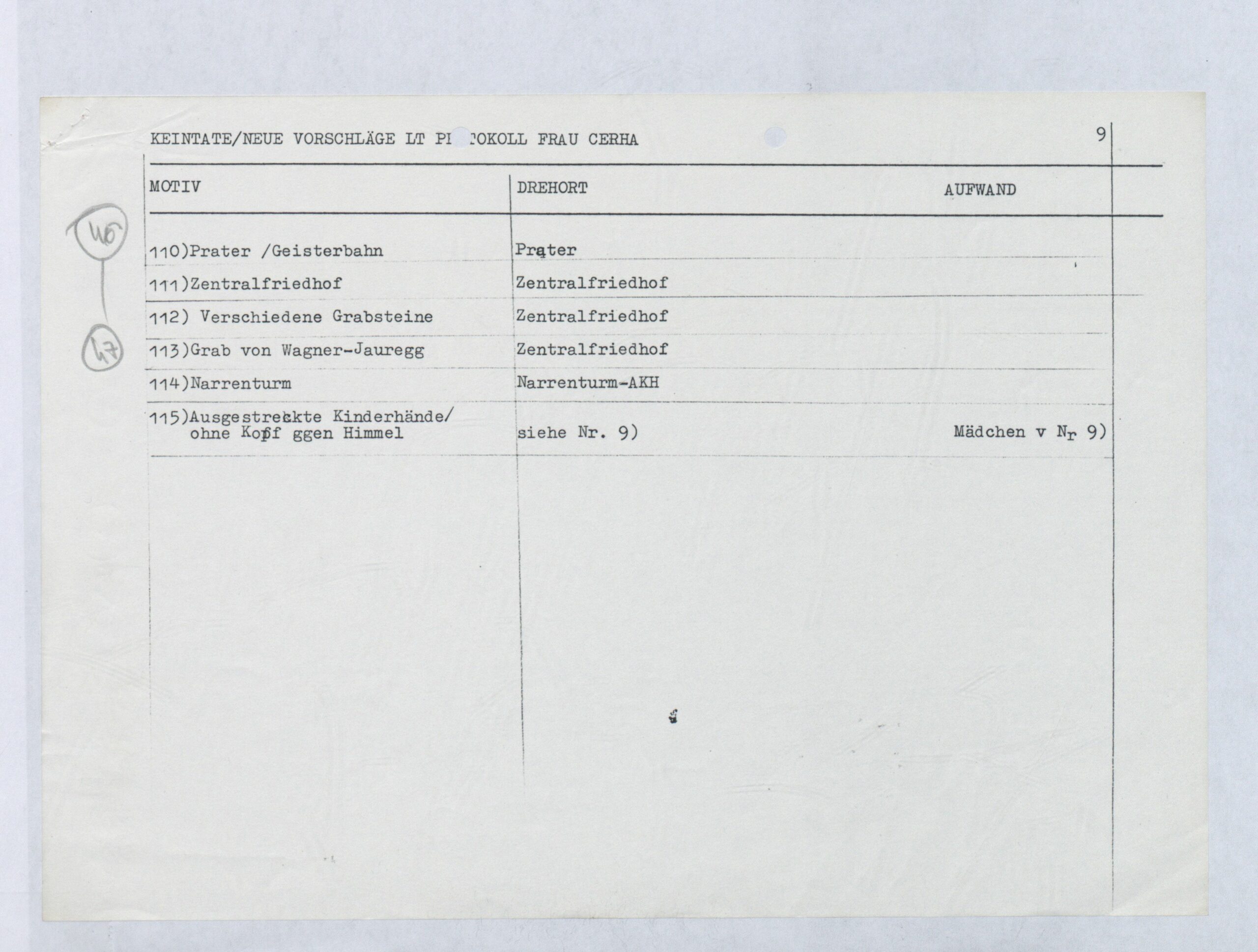

The visual potential of Keintate later paved the way to moving images. The fact that an underlying film concept is tucked away in the slide show was a first hint at the existence of plans for a filmic realisation. A preserved typescript, the date of which is unknown, impressively documents the planning of a television film. The planned shooting locations are all striking Viennese sites: The courtyard of the Metropol, Heurigen Nierscher in the Pötzleinsdorf district, Kärntner Straße in the old town, the catacombs of St. Stephen’s Cathedral, the Ottakringer Cemetary, and the Prater. The guiding theme of the cinematic sequence of locations appears to be a surrealistic foray through the city. For example, the manuscript includes an old photo of H. K. Gruber as a choirboy, superimposed on the Mozart ball logo, and a “cow or carp eye”Typescript of film concept for I. Keintate, AdZ, 000T0084/12 turning into the “blinking eye of a traffic light”—design elements at times reminiscent of Luis Buñuel’s early experimental films.

Typescript with film concept for I. Keintate, time of origin unknown

Although the fragmentation of Keintate sometimes causes it to resemble the colourful refractions of a kaleidoscope, it still creates an impressive arc of suspense. In the last part in particular, the city becomes “documentation of an essential layer of mentality”.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 247 Here, “the phenomena of decay dominate. Delirium, fatalism, and death—age-old themes in folk art and Viennese art”, says the composer. Cerha’s pupil Georg Friedrich Haas, meanwhile himself an internationally renowned composer, attended the Keintate premiere, which took place while he was still studying composition with Cerha. His memories of the performance vividly portray how the darkening of the dramatic arc reached the audience:

The Keintate premiere was unforgettable. Hearing it played for the first time, the audience was initially almost shocked: One would never have expected something so tangible from Cerha. But the early amiable humour drew everyone in with its charm, and soon the mood was downright exuberant and there was roaring laughter. But the humour became more and more bitter, more and more angry; a perfidy reminiscent of “Herr Karl” began to surface. The laughter gradually stifled. It became more and more quiet, until in the end only one woman was still laughing, almost hysterically, until she managed to get herself under control with the help of her partner and she, too, fell silent. An oppressive mood had spread; after all, Gruber was singing about death looking different every time and smelling different every time. Something like a two-layer counterpoint was created: on the one hand, a differentiated and expressive music with countless allusions and sham quotations and, on the other, the linearity of the audience’s reactions (from the carnival to the cemetery).

Georg Friedrich Haas

Georg Friedrich Haas, “Ohne ihn wäre ich ein Anderer geworden. Friedrich Cerha zum Geburtstag”, essay for the Klangforum Wien,

The dramaturgy of Keintate described above demonstrates Cerha’s special flair for integrating small elements into a greater process. Like the walk through Vienna that the planned film would have taken its viewers on, we now invite you for a stroll through the Keintate that is intended to provide at least a hint of the humour and dialect ballads of this work.

Prolog

1 Heans inas au

| Heans inas au | Hören Sie sie an |

| de magaredna | die Margarethner |

| und fünfhausa | und Fünfhauser |

| de flurisduafa | die Florisdorfer |

| und de simaringa | und die Simmeringer |

| de weana | die Wiener |

| miad an wuat | mit einem Wort |

| heans inas | hören Sie sie sich |

| uandlech au | ordentlich an |

| unds wiad ina | und es wird Ihnen |

| gauns woam ums heaz | ganz warm um’s Herz |

| oda se griang | oder Sie kriegen |

| de ganslhaut | die Gänsehaut |

| ans fon de zwaa | eines von beiden |

I. Teil

2 Bei da bost schdimmt aa wos ned

| Bei da bost | Bei der Post |

| schdimmt | stimmt |

| aa wos ned | auch etwas nicht |

| aundas kauni | anders kann ich |

| ma des ned | mir das nicht |

| eaglean | erklären |

| daas i scho | dass ich schon |

| seit ana | seit einer |

| glanan ewigkeit | kleinen Ewigkeit |

| kane libesbriaf | keine Liebesbriefe |

| mea griag | mehr bekomme |

3 Waun i da keisa gwesn waa

| Waun i | Wenn ich |

| da keisa | der Kaiser |

| gewsn waa | gewesen wäre |

| daun hed i | dann hätte ich |

| ole maln | alle Mädchen |

| in da keantnaschdrossn | in der Kärntnerstraße |

| in da brodaschdrossn | in der Praterstraße |

| und aum giatl | und am Gürtel |

| ausbrowiad | ausprobiert |

| und nocha | und nachher |

| hed i gsogt | hätte ich gesagt |

| es woa sea scheen | „Es war sehr schön, |

| es hod mi sea gefreid | es hat mich sehr gefreut“ |

4 Da hime fia uns weana

| Da himme | Der Himmel |

| fia uns weana | für uns Wiener |

| miast a grossa | müsste ein großer |

| schanigoatn sei | Gasthausgarten sein |

| aun an woaman | an einem warmen |

| sumadog | Sommertag |

| und de kona | und die Kellner |

| miastn schizln | müssten Schnitzel |

| und guaknsolod | und Gurkensalat |

| bringa und bia | bringen und Bier |

| sofüü ma wüü | soviel man will |

| und ollas umasunst | und alles gratis |

Cerha’s intention of working with nineteenth-century Wienerlied models is revealed right at the beginning. Sweet and catchy, the swaying melody is particularly distinct in the fourth song, principally in the voice of the two violins, which carry the melodic movement in the brief introduction. Taken on their own, the violin voices could actually have originated from an authentic Viennese song—their two-part melodies consistently moving in the tonal range of E-flat major. However, the clear harmonies are “polluted” by the surrounding voices,Hartmut Krones, “‘Wienerische’ Kompositionen von Friedrich Cerha”, in: Lukas Haselböck (ed.): Friedrich Cerha. Analysen, Essays, Reflexionen, Freiburg et. al 2006, pp. 187–213, here p. 195 f.

with subliminally bizarre notes repeatedly mixing in to create a somewhat “wobbly walk”. However, the direction is never entirely lost: A slow waltz shows the audience the way, the sweet sounds corresponding to the perfect dream world of the lyrics. With a wink, a nod, and a little punch line at the end, the poetry satirises the cosiness of the Viennese soul: “For us Viennese, heaven must be a pub garden on a warm summer day. And the waiters would bring us schnitzel and cucumber salad and all the beer we want. And all of it for free.” Accordingly, the singer’s expression is “dreamy”Designation for the singer, T. 5 and “simple” on the wistful verse, always following along with the violins in delight. Only later does the supposedly safe terrain begin to shudder noticeably, the violin melodies seeping into the murky web of other voices. The cloudiness increases with two brief flashes of musical reference: The two clarinets mockingly join together to play the Viennese folk song “O du lieber Augustin” (which Schönberg also cited in his Zweiten Streichquartett with an even more tragic undertone). Almost at the same time, but slightly offset, the start of the patriotic song “O du mein Österreich”—composed by Franz von Suppè, whom Cerha greatly esteems—can be heard in the two horns.Interview with Friedrich and Gertraud Cerha for “Cerha Online”, 10 September 2019

5 Waasd no wiasd ois weisses mal

|

Waasd no |

Weißt du noch |

|

wiasd ois |

wie du als |

|

weisses mal |

weißes Mädchen |

|

rosnblaln |

Rosenblätter |

|

gsdrad hosd |

gestreut hast |

|

|

|

|

jetzt kumst hintn |

jetzt kommst du hinten |

|

bei de oedn weiwa |

bei den alten Weibern |

|

waun da pfora |

wenn der Pfarrer |

|

midn himme |

mit dem Traghimmel |

|

scho umd nexte |

schon um die nächste |

|

ekn bogn is |

Ecke gebogen ist |

6 De sun is ma zhaas

| Di sun | Die Sonne |

| is ma zhaas | ist mir zu heiß |

| und da reng | und der Rege |

| is ma znos | ist mir zu nass |

| und di ködn | und die Kälte |

| fadrog i scho goaned | vertrag‘ ich schon gar nicht |

| fo miaraus | von mir aus |

| brauchads | bräuchte es |

| iwahaupt | überhaupt |

| ka weda gem | kein Wetter geben |

7 Im grund bin i a guada loodsch

| Im grund bin i | Im Grunde bin ich |

| a guada loodsch | ein gutmütiger Mensch |

| nua haas gee | nur zornig (heilaufen) |

| dua i leichd | werde ich leicht |

| und wauni | und wenn ich |

| haas gee | zornig werde |

| daun fagis i imma | dann vergesse ich immer |

| daas i im grund | dass ich im Grunde |

| a guada loodsch bin | ein gutmütiger Mensch bin |

8 I hoid di du hoidsd mi

| I hoid di | Ich halte dich |

| du hoidsd mi | du hältst mich |

| ea hoid si | er hält sie |

| si hoid eam | sie hält ihn |

| so hoid ana | so hält einer |

| in aundan | den anderen |

| aum schmee | zum Narren |

Kein’s poem “I hoid di du hoidsd mi” (I hold you you hold me) builds up an effective closing punch by means of a simple linguistic variation. The simplicity of the verses, almost like a nursery rhyme, leads to an equally transparent and witty setting with allusions to yodelling. The motif of the song is derived from the yodel hit “Hätt i di” (If I Had You), which was extremely popular in Austria. The typical echoing of sounds across the mountains can also be heard: What the singer sings, accompanied by the viola, is immediately repeated by the violin and cello—creating a veritable canon. The second voice comes in closer during the interlude. Again as a canon, the defining initial motif is unmistakable here, voiced by the folksy Alpine sound of the two clarinets. The busyness of the constantly circling music comes to a standstill in the last lines, casting doubt on what was just heard and leading the listener onto icy terrain.

9 Waunsd amoi brofessa wiasd

| Waunsd amoi | Wenn du einmal |

| brofessa wiasd | Professor wirst |

| daun greng di ned | dann kränk‘ dich nicht |

| des kaun bei uns | das kann bei uns |

| an jedn basian | jedem passieren |

10 An lipizana mecht i

| An lipizana | Einen Lipizzaner |

| mecht i gauns | möchte ich ganz |

| fia mi alaa | für mich allein |

| an lipizana | einen Lipizzaner |

| groos und | groß du |

| weis und | weiß und |

| ausgschtopft | ausgestopft |

| mecht i | möchte ich |

| oda wenigstns | oder wenigstens |

| an sengagnabn | einen Sängerknaben |

11 De darm san in de katakombm

| De darm | Die Gedärme |

| san in de katakombm | sind in den Katakomben |

| es heaz | das Herz |

| is in da augustinakiachn | ist in der Augustinerkirche |

| da keapa | der Körper |

| in da kapuzinagruft | in der Kapuzinergruft |

| so haums di keisarin | so haben sie die Kaiserin |

| marideresia fadeut | Maria Theresia verteilt |

| das ma deimoi | damit man drei Mal |

| zoen muaas | bezahlen muss |

| waumas seng wü | wenn man sie sehen will |

12 Intermezzo (Marsch)

—

II Teil

13 A leich aum otagringa friidhof

|

A leich |

Ein Begräbnis |

|

aum otagringa friidhof |

am Ottakringer Friedhof |

|

ist so schee |

ist so schön |

|

de fogaln singan |

die Vögel singen und die |

|

und d kastanien blian |

Kastanien blühen |

|

di witwe wand |

die Witwe weint |

|

de feterana schbün |

die Veteranenmusik spielt |

|

es riecht noch weirauch |

es riecht nach Weihrauch |

|

und da pfora ret |

und der Pfarrer redet |

|

na wiakli woa |

nein, wirklich |

|

nix schenas ken i ned |

wahr ich kenne nichts Schöneres |

14 I hob a wax heaz

| I hob a wax heaz | Ich hab‘ ein weiches Herz |

| und da winta | und der Winter |

| is schdreng | ist streng |

| und de aumschln | und die Amseln |

| de haum | haben nichts |

| nix zum fressn | zu fressen |

| und drum | und deshalb |

| hob i mei oede | hab‘ ich meine Frau |

| dawiagd und | erwürgt und |

| zaschtiklt | zerstückelt |

| und aufs fenstablech | und auf’s Fensterblech |

| gschdraad | gestreut |

| weu i hob a wax heaz | denn ich hab‘ ein weiches Herz |

| und da winta | und der Winter |

| is schdreng | ist streng |

| und ma deaf ned | und man darf nicht |

| aufd aumschln fagessn | die Amseln vergessen |

There is no shortage of grotesquery in Keintate. The piece “I hob a wax heaz” (I have a soft heart) is a prime example. Kein’s exaggerated murder fantasy tells of the chasm between the good intention of feeding the winter birds and the terrible act of slaughtering his wife. Cerha’s music follows the poem’s “babbling” tone. With no emphasis placed on individual words, the listener is confronted with concentrated fragments of speech that truly leave them speechless. The style of presentation is not based on singing, but rather on a natural way of speaking, with restless words that are supported by an easy-to-recognise accompanying musical pattern. Rapid harmonic sequences on the accordion follow the measured “parlando” of the singer, and the flageolet tones of the string quartet shimmer high above. Cerha uses this distinctive musical combination again in a later number, “das ringlgschbü draad si”, to suggest pleasure—perhaps an indication of Cerha’s interpretation of the macabre poem.

15 Waun i sinia

|

Waun i sinia |

Wenn ich so nachsinne |

|

i dua des oft |

das tu‘ ich oft |

|

i bin a mensch |

ich bin ein Mensch |

|

dea füü siniad |

der viel nachsinnt |

|

und jedesmoi |

und jedes Mal |

|

waun i des dua |

wenn ich das tu‘ |

|

wia soi i sogn |

wie soll ich sagen |

|

a jedesmoi hoid |

jedes Mal halt |

|

waun i so sinia |

wenn ich so nachsinne |

|

nau jo |

na ja |

|

do schlof i ei |

dann schlaf‘ ich ein |

16 Aufschbringa deafst ned

|

Aufschbringa |

Aufspringen |

|

deafst ned |

darf man nicht |

|

oschbringa |

abspringen |

|

deafst ned |

darf man nicht |

|

ausselaana |

hinauslehnen |

|

deafst di a ned |

darf man sich auch nicht |

|

ausschbukn |

ausspucken |

|

deafst ned |

darf man nicht |

|

min foara redn |

mit dem Fahrer sprechen |

|

deafst ned |

darf man nicht |

|

und do hasts ollaweu |

und da wird immer behauptet |

|

bei uns is ma |

dass man bei uns |

|

a freia mensch |

ein freier Mensch ist |

17 Do sans maschiad

|

Do sans maschiad |

Da sind sie marschiert |

|

de buagschandam |

die Hofburgwache |

|

es bundeshea |

das Bundesheer |

|

de deidschn und |

die Deutschen und |

|

de russn |

die Russen |

|

|

|

|

jo do aum ring |

ja, da über die Ringstraße |

|

do sans maschiad |

da sind sie marschiert |

|

da schuzbund und |

der Schutzbund und |

|

de haunanschwanzla |

die Heimwehr |

|

de nazi und |

die Nazis und |

|

de kumaln |

die Kommunisten |

|

|

|

|

und i |

und ich |

|

woa oeweu |

bin immer |

|

in schbalia |

im Spalier gestanden |

18 Glauma des ollas sumiad si

|

Glauma des |

Glaub‘ mir das |

|

ollas sumiad si |

alles summiert sich |

|

und wauns aa |

und wenn es auch |

|

nau a so gla is |

noch so klein ist |

|

heit wos |

heute etwas |

|

und muang wos |

und morgen etwas |

|

und iwamuang |

und übermorgen |

|

aa wos |

auch etwas |

|

sumiad si |

summiert sich |

|

und wiad da |

und wird dir |

|

amoi zu füü |

eines Tages zu viel |

19 Gee nua eine kum nua ausse

|

Gee nua eine |

Geh‘ nur hinein |

|

kum nua ausse |

komm‘ nur heraus |

|

schdeig nua auffe |

steig‘ nur hinauf |

|

greu nua owe |

kriech‘ nur hinunter |

|

|

|

|

wiasd scho segn |

wirst schon sehen |

|

wosd hikumst |

wo du hinkommst |

20 A glosaug miasd ma haum

|

A glosaug |

Ein Glasauge |

|

miasd ma haum |

müsste man haben |

|

daun ded ma |

dann würde man |

|

fon dem ölend |

von dem Elend |

|

umadum |

rundherum |

|

nua mea |

nur mehr |

|

di höfte seng |

die Hälfte sehen |

|

und des waa |

und das wäre |

|

aa nau gnua |

auch noch genug |

21 De retung und de feiawea

|

De retung und |

Die Rettung und |

|

de feiawea |

die Feuerwehr |

|

de heari geen |

die hör‘ ich gerne |

|

do deng i daun bei mia |

da denk‘ ich mir dann |

|

es brend oda jetzt hods |

es brennt, oder jetzt ist |

|

scho wiida an darend |

schon wieder einer verunglückt |

|

und i bin daun |

und dann bin ich |

|

a bissl draureg |

ein wenig traurig |

|

und a bissl froo |

und ein wenig froh |

|

i man |

i glaub‘ |

|

i dua mi daun |

ich fühl‘ mich dann |

|

genauso fün wia waun |

genau so, wie wenn |

|

de schramen schbün |

die Schrammeln spielen |

22 Intermezzo (Marsch)

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

III Teil

23 Daas ma laud schdadisdig

| Daas ma laud | Dass wir laut |

| schdadisdig | Statistik |

| wenig saf | wenig Seife |

| fabrauchn dan | verbrauchen |

| is logisch | ist logisch |

| weu bei uns | denn bei uns |

| woschd ee | wäscht ohnehin |

| a haund di aundare | eine Hand die andere |

24 Di daunau gibds

|

Di daunua gibds |

Die Donau gibt’s |

|

und hoche heisa |

und hohe Häuser |

|

hauma mea wia gnua |

haben wir mehr als genug |

|

an bam finst scho |

einen Baum findest du schon |

|

in glanstn bak |

im kleinsten Park |

|

de gas is aa ned |

das Erdgas ist auch nicht |

|

iwanesig deia |

übermäßig teuer |

|

|

|

|

mid an wuat |

mit einem Wort |

|

bei uns schdeen da |

bei uns stehen dir |

|

olle meglichkeitn offn |

alle Möglichkeiten offen |

gs.

25 Wauns da fua augn hoidsd

|

Waunsdaa |

Wenn du dir |

|

fua augn hoidsd |

vor Augen hältst |

|

wos heitzudog |

was heutzutage |

|

a leich kost |

ein Begräbnis kostet |

|

daun bleibt da |

dann bleibt dir |

|

goanix aundas iwa |

gar nichts anderes übrig |

|

ois wia weidazlem |

als weiterzuleben |

26 Schee woans jo ned de waunzn

|

Schee woans jo ned |

Schön waren sie ja nicht |

|

de waunzn |

die Wanzen |

|

ubd grochn haums |

und gerochen haben sie |

|

aa ned guad |

auch nicht gut |

|

|

|

|

owa ma is si |

aber man ist sich |

|

wenigstns ned |

wenigstens nicht |

|

so falossn fuakuma |

so verlassen vorgekommen |

|

wia jezt |

wie jetzt |

27 Daas ma oft de foam wexln

|

Daas ma oft |

Dass wir oft |

|

de foam wexln |

die Farben wechseln |

|

des is aa |

das ist auch |

|

so a faleimdung |

so eine Verleumdung |

|

nim zum beischbüü |

nimm zum Beispiel |

|

de magirungan |

die Markierungen (der Wege) |

|

in winawoed |

im Wienerwald |

|

de haum si |

die haben sich während |

|

de gaunze zeid |

der ganzen Zeit |

|

ned gendat |

nicht verändert |

28 Waun i a baafleisch iis

|

Waun i a |

Wenn ich |

|

baafleisch iis |

Beinfleisch esse |

|

do foin ma glei |

dann fallen mir gleich |

|

d fiaka ei |

die Fiaker ein |

|

da brodfisch |

der Bratfisch |

|

und di meri wetschera |

und die Mary Vetsera |

|

da graunprinz rudoif |

auch der Kronprinz Rudolf |

|

und a meialing |

und Mayerling |

|

und dafau kumts |

und daher kommt es |

|

daas i waun i |

dass ich wenn ich |

|

a baafleisch iis |

Beinfleisch esse |

|

oeweu so |

immer so |

|

melancholisch bin |

melancholisch bin |

29 Da fassldiwla san scho ausgschduam

|

De fassldiwla |

Die Biertippler |

|

san scho ausgschduam |

sind schon ausgestorben |

|

wia de dschikaretira |

so wie die Zigarettenstummel-Sammler |

|

de dschikaretira |

die Zigarettenstummel-Sammler |

|

san scho augschduam |

sind schon ausgestorben |

|

wia de balschdira |

so wie die Typen, die in den Abfällen nach Knochen stieren (um sie an Seifenfabriken zu verkaufen) |

|

de balschdira |

die Knochenstierer sind |

|

san scho ausgschduam |

schon ausgestorben |

|

wia de fassldiwla |

so wie die Biertippler |

|

|

|

|

und mia |

und wir |

|

mia kuman a |

wir kommen auch |

|

boid drau |

bald dran |

30 Des ringlgschbü draad si

| Des ringlgschbü | Das Ringelspiel (Karussell) |

| draad si und draad si | dreht sich und dreht sich |

| und du sitzt | und du sitzt |

| auf dein hoizanan pfead | auf deinem hölzernen Pferd |

| und fagissd gauns | und vergisst ganz |

| daas amoi | dass es einmal |

| wiida schtee bleibt | wieder stehen bleibt |

The word “ringlgschbü” is an Austrian dialect word for carouselhttps://www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Ringelspiel. Kein’s poem was originally published in his book of poems Wiener Grottenbahn, aptly referring readers to the site of the Wiener Prater. Carousels have been part of the famous amusement park since its beginnings in the eighteenth century, when they were still turned using sheer muscle power. In the poem, this symbol of amusement becomes a symbol of life, which—at some point—stops turning.

Taking the homage to the Prater literally, the musical setting of the poem implements the idea of the slowing carousel with great plasticity. The drummer brings the idea to life, making clinking sounds with Japanese panes of glass or chains bound together. The rest of the ensemble plays exaggerated carousel music. The bright overtones of the strings capture the sound of a badly oiled carnival ride, creating an acoustic tableau. The colourfully shimmering harmonies of the accordion transport the circus-like atmosphere of the Prater to the listener’s ear, but then the various elements are gradually dismantled. The slowing down spans almost the entire piece, allowing the carousel to come to a very perceptible stop.

31 Beredn dan sas de leid

|

Beredn dan sas |

Sie reden darüber |

|

de leid |

die Leute |

|

waunsd dschechasd |

wenn du säufst |

|

owara bessas mitl |

aber ein besseres Mittel |

|

gengan duaschd |

gegen den Durst |

|

des wissns ned |

wissen sie nicht |

32 De schlechte zeid hod uns ned guad dau

|

Di schlechte zeid |

Die schlechte Zeit |

|

hod uns ned |

hat uns nicht |

|

guad dau |

gut getan |

|

und di guade |

und die gute |

|

duad uns |

tut uns |

|

aa ned guad |

auch nicht gut |

|

wos woin mia |

was wollen wir |

|

eigndli |

eigentlich |

IV Teil

33 De ringldaum

| De ringldaum und | Die Ringeltauben und |

| de duatldaum und | die Turteltauben und |

| de waundadaum und | die Wandertauben und |

| de diakndaum und | die Türkentauben und |

| de schtrossndaum und | die Straßentauben und |

| de rauchfaungdaum und | die Rauchfangtauben und |

| de briafdaum und | die Brieftauben und die |

| de hausdaum und | Haustauben und |

| de lochdaum | die Lachtauben |

| de ludan scheissn | die Luder scheißen |

| oilas au | alles an |

The opening number of the fourth Keintate section is dedicated to an urban animal well-known to all: the pigeon. Like a visitor on a park bench, the poem observes and enumerates all possible types of the birds, at the same time opening the treasure trove of Viennese zoological dialect vocabulary. One of the listed species is not a bird at all. The Viennese word “Rauchfangtaube” (“chimney pigeon”) is a disparaging term for an old woman. The insult is not only brushed over in the poem—the music also ignores it with great indifference. Cerha starts out with a Viennese melody that almost seems like a quotation, but is actually not. The music first wraps the lyrics in a musical declaration of love—concealing the actual message (just as the insult is hidden). Like an operetta, the second stanza trails into the grotesque, which crescendos into an exhausting tongue twister. In the third stanza, the lyrical tone of the beginning is taken up again with equal emotionality. But the path leads one astray—or rather straight into a typical Kein punch line. As in the other numbers, the gracious timbre of the vocalist comes to an abrupt end, giving way to typical Viennese aggravation.

34 Fois se a fremda san

|

Fois se a fremda san |

Falls Sie ein Fremder sind |

|

und noch wean kuman |

und nach Wien kommen |

|

daun schdeigns glei |

dann sollten Sie gleich |

|

uam schdefansduam auffe |

auf den Stephansturm hinaufsteigen |

|

und schauns owe aum grom |

und auf den Graben hinunterschauen |

|

aufs rodhaus und |

auf’s Rathaus und |

|

auf di wotifkiachn |

auf die Votivkirche |

|

und daun ume zum koenbeag |

und dann hinüber zum Kahlenberg |

|

zua daunau und zum risnral |

zur Donau und zum Riesenrad |

|

und wauns des dau daum |

und wenn Sie das getan haben |

|

schdeigns owa fon schdefansduam |

dann steigen Sie herunter vom Stephansturm |

|

und foans gschwind wiida ham |

und fahren schnell wieder nach Hause |

35 I woa scho in kaoale

|

I woa scho |

Ich war schon |

|

in kaoale |

in Caorle |

|

in jesolo |

in Jesolo |

|

und auf da insl rab |

und auf der Insel Rab |

|

|

|

|

i ken di wöd |

ich kenne die Welt |

|

mia kenans nix |

mir können Sie nichts |

|

dazön |

erzählen |

36 De gmiadlichkeit des kaunst ma glaum

|

De gmiadlichkeit |

Die Gemütlichkeit |

|

des kaunst ma glaum |

das kannst du mir glauben |

|

de geed ma iwa ollas |

die geht mir über alle |

|

und waunstas |

und wenn du’s |

|

ned glaubst |

nicht glaubst |

|

schleich di glei |

dann scher‘ dich zum Teufel |

|

weu sunsta leansd |

sonst lernst du |

|

mi kena |

mich kennen |

37 Intermezzo (Galopp)

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

38 Wauma uns min dreg und midn leam

|

Wauma uns |

Wenn wir uns |

|

min dreg |

mit dem Dreck |

|

und midn leam |

und mit dem Lärm |

|

söwa umbrocht |

selbst umgebracht |

|

haum wean |

haben werden |

|

daun wiad |

dann wird |

|

ned amoi mea |

nicht einmal mehr |

|

ana do sei |

einer da sein |

|

dea sogt |

der sagt |

|

recht gschicht eich |

recht geschieht euch |

|

es depm |

ihr Idioten |

39 Intermezzo (Polka)

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

40 I sog da heit gibds nua mea gfrasta

|

I sog da |

Ich sag‘ dir |

|

heit gibds nua mea |

heute gibt’s nur mehr |

|

gfrasta |

unredliche Menschen |

|

wosd hischausd |

wo man hinschaut |

|

sogoa am söwa |

sogar sich selbst |

|

kauma nimma draun |

kann man nicht mehr trauen |

41 Waun i singa kent wiara kanari

|

Wauni singa kent |

Wenn ich singen könnte |

|

wiara kanari |

wie ein Kanarienvogel |

|

daun wari |

dann wäre |

|

in gaunzn dog |

ich den ganzen Tag |

|

schdüü |

still |

|

|

|

|

auf de oat |

auf diese Weise |

|

dedad i eich olle |

würde ich euch alle |

|

schdrofm |

bestrafen |

42 Zeascht schtingn de kaneu

| Zeascht schtingn | Zuerst stinken |

| de kaneu | die Kanäle |

| daun kumt da wind | dann kommt der Wind |

| und drogt | und wirbelt |

| de kasbabialn | die Papierfetzen |

| bis in dritn schtog | bis zum dritten Stock |

| und nocha schitts | und dann regnet es |

| fileicht a hoiwe schtund | vielleicht eine halbe Stunde |

| daasd glaubst | dass man glaubt, |

| di wöd geed unta | die Welt geht unter |

| waunsd owa daun | wenn du aber dann |

| es fensta wiida aufmoxt | das Fenster wieder öffnest |

| is di luft | ist die Luft |

| di fon da schmöz | die von der Schmelzwiese |

| umawaat | herüberweht |

| so gschmackig und küü | so würzig und kühl |

| ois wira mentoizukal | wie ein Mentholbonbon |

Many of the Keintate numbers convey more or less a single mood, though the song “Zeascht schtingn de kaneu” (the canals stink first) is an exception. It is one of the pieces with the most wide-ranging expression, due to the poem itself, which is littered with sensory impressions. It can be roughly divided into two halves: An apocalyptic atmosphere dominates the first, with a dark haze that clears in the second. A coming storm is described and illustrated through music: Ghostly strings echo the underground canal, agitated clarinets blow scraps of paper into a whirl, the harsh sounds of the wind instruments bring the rainstorm thundering down. In the second part, the mood changes to one of indulgence, albeit with a false bottom. The Schmelzwiese, the origin of the “peppery” smell, is a former training ground of the Austro-Hungarian Army—and here, the sound of the storm becomes indistinguishable from a military roar. The strings in particular underline the lyrical descriptions of the air smelling like a “menthol candy” in an unearthly way. The expressive aftermath is reminiscent of the particularly lyrical moments of the Vienna School. Here, the beautiful and the horrifying are united with great poetic power.

43 Mi kenan olle liawa hea

|

Mia kenan olle |

Mich können alle |

|

liawa hea |

lieber Herr |

|

de wochta und |

die Polizisten und |

|

de feiawea |

die Feuerwehrleute |

|

und a es |

und auch das |

|

gaunze mülidea |

ganze Militär |

|

de ralfora |

die Radfahrer |

|

de autofora |

die Autofahrer |

|

de oaman und |

die Armen und |

|

de reichn |

die Reichen |

|

de greisla |

die Gemischtwarenhändler (Greisler) |

|

de greila |

die Gemüsehändler (Kräutler) |

|

de müliweiwa |

die Milchweiber |

|

de rodn und |

die Roten und |

|

de schwoazn |

die Schwarzen |

|

de wiatn |

die Wirte |

|

und kafeesiada |

und Cafétiers |

|

de schuasta |

die Schuster |

|

schneida und de |

Schneider und die |

|

schdrossnkira |

Straßenkehrer |

|

de hean beaumtn |

die Herren Beamten |

|

und minista |

und Minister |

|

de bem |

die Tschechen (Böhmen) |

|

de gscheadn |

die Provinzler |

|

und growodn |

und Kroaten |

|

de hausmasta |

die Hausmeister |

|

de dramweia |

die Straßenbahner |

|

mi kenan olle |

Mich können alle |

|

liawa hea |

lieber Herr |

|

und se wauns woin |

und Sie, wenn sie wollen, |

|

se a |

Sie auch |

Epilog

44 Intermezzo

45 Wiama seinazeid auf da greizeichnwisn

|

Wia ma seinazeid |

Als wir damals |

|

auf da greizeichnwisn |

auf der Kreuzeichenwiese (im Wienerwald) |

|

babla gfaungt haum |

Schmetterlinge fingen |

|

hauma nau ned gwusd |

haben wir nicht gewusst, |

|

daas mar amoi |

dass wir einmal |

|

so gfaungt und daun |

so gefangen und dann |

|

mid ana |

mit einer |

|

unsichtboan nodl |

unsichtbaren Nadel |

|

auf an |

auf einem |

|

unsichtboan bopandekl |

unsichtbaren Karton |

|

gschbenld wean |

angenadelt würden |

46 A fietl und no a fietl

|

A fietl |

Ein Viertel(liter) |

|

und no |

und noch |

|

a fietl |

ein Viertel |

|

und no |

und noch |

|

a fiatl |

ein Viertel |

|

und no |

und noch |

|

a fietl |

ein Viertel |

|

|

|

|

und daun |

und dann |

|

waun |

wann |

|

daun |

dann |

|

|

|

|

a fiatl |

ein Viertel |

|

und no |

und noch |

|

a fietl |

ein Viertel |

|

und no |

und noch |

|

|

|

|

und daun |

und dann |

|

waun |

wann |

|

no daun |

na dann |

|

jo daun |

ja dann |

47 Fria hob i glaubt

| Fria hob i glaubt | Früher hab‘ ich geglaubt |

| daas da dod | dass der Tod |

| ollaweu gleich ausschaut, | immer gleich aussieht |

| so wi dea | so wie der |

| in da geistabaun | in der Geisterbahn |

| und noch leim riachd | und nach Leim riecht |

| und schtaub | und Staub |

| oba jetzt waas i | aber jetzt weiß ich |

| daas a ollaweu | dass er immer |

| aundas ausschaut | anders aussieht |

| und ollaweu | und immer |

| aundas riachd | anders riecht |

References to the Wienerlied can also be heard in the numbers of the epilogue. In the last part, however, the lovely aura of familiar music is lost, transformed into something gruesome that, aptly, corresponds with Kein’s morbidly revolving poems. In 1969, Georg Kreisler sang “Der Tod, das muss ein Wiener sein” (Death Must Be Viennese), not without reason—a focus on death and decay has a long tradition in the cultural history of the Austrian capital.

In the third to last song of the cycle, death takes on an especially clear shape. Kein’s poem is based on the unsophisticated depictions of death found in tunnels of horror, such as the one in the haunted house at the Wiener Prater, the oldest in Austria, built in 1933. The kitschy paintings on the fair ride contrast with the described personal experiences of death, which can arrive in an infinite number of forms.

Cerha meets the poem with a branching musical image. Right at the start, the cello develops a line, which is then taken up by other instruments shortly after the first notes. The lower instruments (including a bass clarinet) draw it downwards, while the higher ones (such as the violins) pull it upwards in an inverted form. The numerous variants infiltrate each another, intertwining, creating a soundscape for the singer’s story before finally flowing into darkness.

48 Da wagna jaurek is scho laung dood

|

Da wagna jaurek |

Der Wagner-Jauregg |

|

is scho laung dod |

ist schon lange tot |

|

und in hoff gibds |

und den Hoff gibt es |

|

jetzt a nimma mea |

jetzt auch nicht mehr |

|

|

|

|

schee schauma aus |

schön schau’n wir aus |

|

mia iaman noan |

wir armen Narren |

49 Waun an fiemling

|

Waun an fiamling |

Wenn einem Firmling |

|

da luflbalaun |

der Luftballon |

|

dafaufliegd |

davonfliegt |

|

daun sog i imma |

dann sag‘ ich immer |

|

waan ned glana |

wein‘ nicht, Kleiner |

|

wea waas fia |

wie weiß, |

|

wos guad is |

wofür’s gut ist |