Klavierstücke für Kinder

oder solche,

die es werden wollen

What do adults know anyway …

Piccola commedia

Konzert für Violine, Violoncello und Orchester

Irina Cerha, Kinderspielplatz (edited), undated

While some of Irina Cerha’s drawings relate directly to her father’s music, others stand on their own. The drawing Kinderspielplatz (Playground) is one of the artist’s early works and is not connected with any specific piece. Nonetheless, the playful design fits well with Klavierstücke für Kinder oder solche, die es werden wollen (Piano Pieces for Children, or Those Who Want to Become One).

Foto: Christoph Fuchs

Like father like daughter?

Source: Robert Neumüller/Irina Cerha

Director Robert Neumüller shot scenes for a film portrait of Cerha titled So möchte ich auch fliegen können (So, Too, Would I Like to Fly). He traces the story of Friedrich Cerha’s development as a person and a composer. While filming, Neumüller also interviewed his daughters Irina (*1956) and Ruth (*1963). Both are artistically active, but (despite learning to play instruments) did not choose music as their primary medium of expression. Ruth made her mark as a writer, and Irina’s passion was in the visual arts. As a child, she often reached for a pencil, capturing her mental images on sheets of paper. Several of her expressive childhood drawings are intertwined with her father’s work in a very special way; they accompany a cycle of piano pieces Friedrich composed for Irina.

Außenansicht

Klavierstücke für Kinder oder solche, die es werden wollen emerged in an environment that contradicted them in many respects. Almost all of the pieces were written in 1964, with a few composed earlier. The experimental and investigative spirit of the 1960s, and Cerha’s avant-garde orientation at the time, hardly fit with the miniature, witty, and simple pieces. The only piece composed a year earlier, Elegie for piano, is an indication of how greatly Klavierstücke für Kinder differ from the other works of this period.

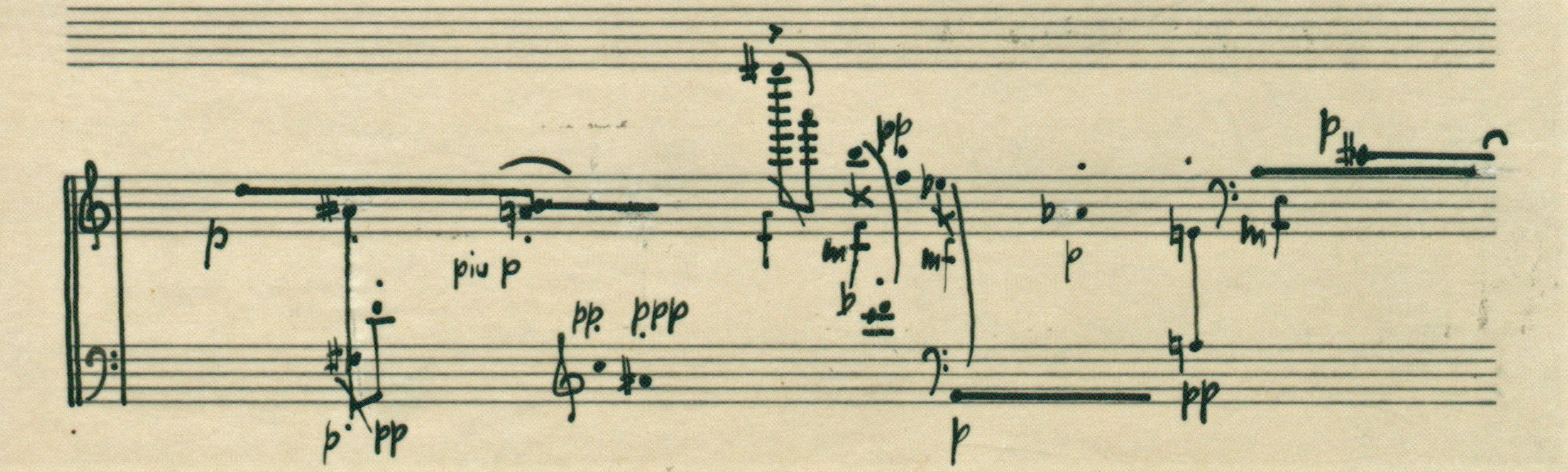

Cerha, Elegie for piano, handwritten score, line 1, 1963

Cerha, Elegie for piano (1963)

Interpreter: Wolfram Weiss

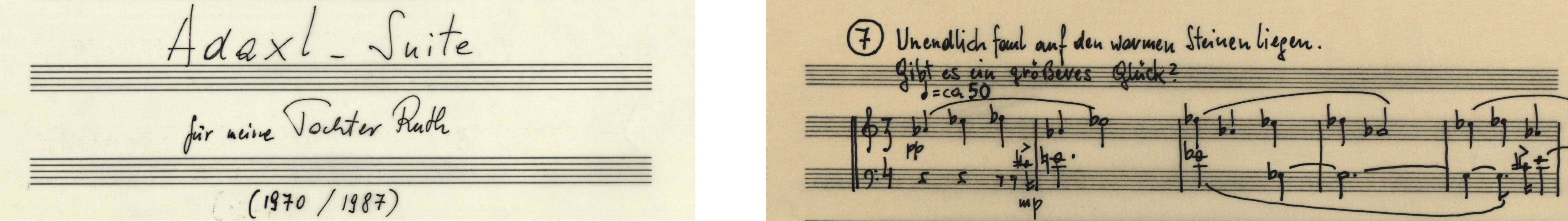

Elegie communicates a concentrated, exciting and solemn fabric of tonal abstraction — and Klavierstücke, a colourful game of gestures, movement, and imagery. Contrasts like this make it clear that Cerha’s oeuvre does not categorically exclude anything whatsoever. The arc of his artistic development is characterized just as much by a sense of broad coexistence as it is by stringent detail. At the same time, one can clearly recognize Cerha’s typical way of working in Klavierstücke: Smaller pieces are almost always composed in parallel to the large ones. They arise not from sustained exertion but from spontaneous expression. Cerha worked particularly intensively on his large-scale Exercises– project in 1964 — the same year that he wrote Klavierstücke and several other small pieces for piano, including Fünf kleine Stücke, a duet with clarinet, and Sieben Anekdoten, with flute. Of all these small works, it is the Klavierstücke that stand out, uniquely dedicated to Irina and “to children”. However, this was not Cerha’s only composition for young fingers and ears. He later also wrote a piano cycle for his second daughter, Ruth. In 15 imaginative pieces, Adaxl-Suite describes the life of a lizard (Adaxl in Austrian dialect), inspired by the lizards that Friedrich and Ruth “often observed on the warm stones“Cerha, text to Adaxl-Suite, AdZ, 000T0076/2 around Maria Langegg.

Cerha, Adaxl-Suite, handwritten score, excerpts, 1987, AdZ, 00000076

Brücke

In writing piano music for children, Cerha joined a tradition that produced particularly important works during the nineteenth century. This focus on young audiences was rooted in a broad cultural and historical background: With the dawn of the Enlightenment, people moved away from the idea of seeing children as flawed beings who only became full-fledged humans once they reached adulthood. Closer attention was paid to the first phase of life. “Childhood,” said Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “has its own way of seeing, thinking, and feeling, and nothing is more foolish than trying to substitute our own for them.“ Jean Jacques Rousseau, Émile, or Treatise On Education, D. Appleton and Company 1909, p. 54A logical consequence of this thinking was the idea that children should not play the same music pieces as their parents; it was necessary to create their own. This resulted in the emergence of a separate market segment of music for children. In many cases, the composers were established artists: Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Stephen Heller, Peter Tchaikovsky, and Carl Reinecke. One name in particular resonates to this day: Robert Schumann. He composed, for example, Zwölf vierhändige Klavierstücke für kleine und große Kinder (a title that relates to Cerha’s piano cycle) and, in 1848, the notorious Album für die Jugend—the yardstick for children’s piano pieces par excellence. Schumann’s Album reveals characteristics of the children’s music genre with particular clarity, divided into one section “for little ones” and another “for adults”. The pieces in the album are mostly quite short—many fill only about half a page of music—and convey moods that correspond with their titles: Soldatenmarsch, Jägerliedchen, Wilder Reiter, or Knecht Ruprecht.

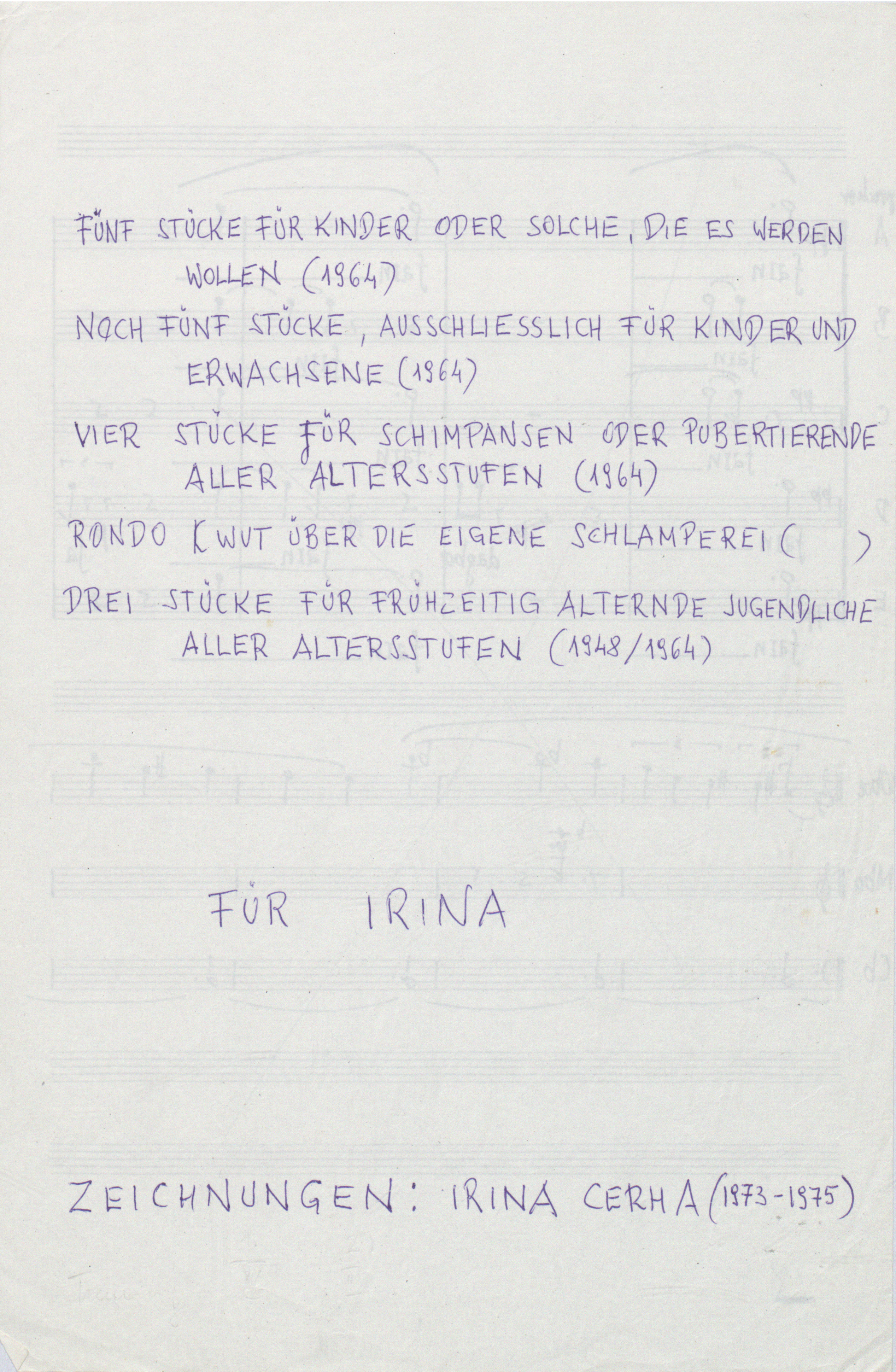

Both of these properties are also found in Cerha’s Klavierstücken für Kinder. Each composition has at least one name, sometimes even several, and most are just a few lines long. As in Romantic character pieces, each piece is imbued with a poetic idea that intertwines with the title. The multiple titles reveal a sense of humour and enjoyment of double meanings. They are also designed to stimulate the reader’s own imagination, issuing an open invitation to complete the titles any way one would like. Finally, like Schumann’s Albumblätter, Cerha’s pieces are divided into sections for pianists of different levels and ages. Although the target groups are deliberately left unclarified (using ambiguous designations such as “exclusively for children and adults”), they don’t lack focal points. The first ten pieces are dedicated to the younger child’s world of experience (however it is expressed), while the remaining eight focus more on older youth. On a manuscript page for the publisher, Universal Edition, Cerha summarizes the sections, including their year of origin.

A Duet, wood engraving for Harper's Young People, Vol. 9/419, 1887

Quelle: Hathi Trust Digital Library

Another aspect that distinguishes Cerha’s Klavierstücke is their often very personal nature. His daughter left her mark between the staves, and the predominantly “parodistic characters” Cerha, text on Klavierstücke für Kinder, oder solche, die es werden wollen, AdZ, 000T0067/2 can be traced back to her. Ever since she was a child, she “particularly loved […] goofing around” with her father—something the music gently captures. But Irina Cerha was also a creative contributor to the collection: “At around the age of 13, she began to draw intensively.” For the print edition of Klavierstücke, in the 1970s, she and her father selected a number of well-suited, “sometimes cartoonish drawings”. The small-format drawings were then printed alongside the music notes. This is yet another connection to Album für die Jugend, as Schumann had also planned to have his pieces illustrated—although he ultimately never realised the idea.Schumann wrote to his colleague Carl Reinecke that he was planning to include an illustration for each piece, however, it was not possible to carry this out due to the publisher’s schedule and too little time. See Erler, Robert Schumanns Leben, Vol. 2, p. 62

Irina Cerha, various drawings, in the 1970s

Foto: Christoph Fuchs

Irina Cerha returned to the pieces dedicated to her in the year 2020. She had played them since she was a child, but now, on the occasion of her father’s upcoming 95th birthday, she recorded all the compositions, played on her own piano, for the first time. She produced a video, combining the recordings with her drawings—a gift that celebrates a merging of visual and acoustic art and is at the same time a testament to the intimate relationship she had with her father.

Innenansicht

Cerha Online was able to acquire the viewpoint of an expert for their observations on Klavierstücke für Kinder: In 2019 Univ.-Prof. Dr. Anne Fritzen wrote her PhD thesis on the opera Der Riese vom Steinfeld and studied piano (both performance and education) at the University of Music and Theatre Leipzig. She is currently a professor at the Hochschule für Musik “Franz Liszt” in Weimar. She wrote a guest commentary for this platform:

Cerha’s Klavierstücke für Kinder oder solche, die es werden wollen (1964) is—as the name suggests—a collection, which in turn consists of four smaller collections plus a single piece.Take, for example, the titles (here all in translation), “Five Pieces for Children or Those Who Want to Become One”; “Five More Pieces, for Children and Adults Only”; “Four Piano Pieces for Chimpanzees or Adolescents of Any Age”; a rondo subtitled “Anger at One’s Own Sloppiness”; and “Three Pieces [For Precocious Youth (Of All Ages)]”.

Although a certain education focus can be found both in the increasing degree of difficulty of the pieces, from easy couplets to mid-level two-part pieces and in the title,This makes it one of Cerha’s few pedagogical works. His other pedagogical works include the Adaxl-Suite für Klavier (1970/1987), Volume 2 of Klavierstücke für Kinder (2016/17), Bekenntnis, for a children’s choir (2008), and—depending on your viewpoint—Cerha’s 21 naseweise Notizen für Klavier (2016) and Zebra-Trio (2010).the pieces are not aimed solely at children, as the titles of the collections and the individual compositions make abundantly clear. The music appeals to anyone who doesn’t take themselves too seriously, and who enjoys ironic undertones and nuances.

The topics of the first pieces touch on the questions children deal with during their first few piano lessons—for example, referring to the piano teacher, “Is He or She Strict? Or Not Strict?” The answer is demonstrated by how much precise attention the teacher pays to implementing Cerha’s detailed instructions on dynamics and articulation in the unisono movement. Cerha also plays with ever-tiresome topics such as “counting”: The piece “This Darn Counting” plays with repeated time signature changes and leaves it up to the performer to decide whether the crazy tangle of time changes is fun or not with the subtitle “What Do Adults Know About What’s Fun for Kids Anyway!”

In another “amusement”—this time probably more for the benefit of those already somewhat versed in music—Cerha makes references to various composers in “Pieces for Children”. “Grandma’s Dance”, for example, uses constantly changing time signatures and sharp accentuation to create humour, as does Igor Stravinsky. However, Cerha also places accents and motifs in such a way that the metre seem to “limp”, thus imitating the dance of an elderly, slightly frail lady. On the other hand, Cerha’s rondo, subtitled “Anger at One’s Own Sloppiness”, is inevitably reminiscent of Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Rondo a Capriccio” op. 129, “Rage Over a Lost Penny”. Cerha freely combines Beethoven motifs, sometimes “sloppily” skipping over beats and bars, as in the “raging” example. Further allusions and ironic observations range from Carl Czerny (“Looking in the Mirror Is Stupid!!” and “But Monotony Is So Pleasantly Soothing”) to Béla Bartók (“A Journey to the Balkans”) and Eric Satie (“Life Is Far Too Exciting” and “Children Have the Right to a Psychiatrist, Too”).

In addition to all the wackiness and irony, several pieces also resonate with seriousness and thoughtfulness, such as “The Bad Hand” and “Apparently the Police Are Necessary”. Here, the performer is asked to hit one hand with the other hand to create a sound, which is then picked up with the pedal to create an echo. This imitates the act of being punished, both literally and acoustically.

All of this creates an oscillation between fun and seriousness, between being a child and an adult, with the boundaries between who is fun and who is serious, who is reasonable and who is far-sighted remaining fluid and ironically shifting again and again. In all pieces, says Cerha, “all rights are reserved for the children (including writing new fingerings and suggestions for improvement).” This gives them both the opportunity to democratically participate in the lesson and also allows them to creatively engage with the material, because, as Cerha writes in the foreword: “Who really knows what’s fun for kids?”

We were able to win over two young students from the Gustav Mahler Private University as interpreters of the pieces, expressly for the Cerha Online project. Paula Liebhauser and Hannah Senfter worked on the piano pieces together with Anne Fritzen, recording them all in 2020. These video recordings guide us through the cycle again—this time, however, from a different perspective and supplemented by brief musical commentary.

Klavier: Paula Liebhauser

Ton & Schnitt: Bruno Singer

Klavier: Hannah Senfter

Ton & Schnitt: Bruno Singer