The Violinist

Cerha on violin, Brussels 1958

Cerha’s activities as a concert violinist took on an equal footing with composing in the 1950s. When the world exhibition was held in Brussels in 1958, he played Hanns Jelinek’s new violin pieces in a class.

Photo: Archiv der Zeitgenossen

3/4 violin, Friedrich and Gertraud Cerha’s private collection, Vienna

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

Someone who starts playing the violin at a very early age usually ends up owning several instruments over the course of their life. In addition to the full-sized violin made for adults, there are six other sizes for children. Friedrich Cerha began studying the stringed instrument at the age of seven—and while he did not keep his childhood violin for long, he later bequeathed it to his daughter, Ruth. It was not until the 1950s that Cerha found his steady “companion”, a violin by Bavarian luthier Sebastian Klotz. Unfortunately, like his first violin, this instrument is no longer in good condition. Only his young-adult violin (see photo above) survived the decades for the most part unscathed.

Throughout European music history, the violin has been the chosen instrument of many composers, from Antonio Vivaldi to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Lili Boulanger, Paul Hindemith, and Caroline Shaw. Many of these musicians also played their own works—something that is now somewhat of an exception. Starting in his younger days, Cerha always closely related playing the violin with composing, and the two activities coexisted for him over the course of decades. In the 1950s and 1960s, he regularly performed as a concert violinist, only giving up performing when he (and the public) came to understand that his composed works were central, giving them a new intensity. Conducting and teaching also pushed playing the violin into the background. However, his experiences as an active maker of music taught him to always view imagination and interpretation as an enriching interplay, an understanding that shaped Cerha as an artist throughout his lifetime.

The Violin as a Door to the World of Music

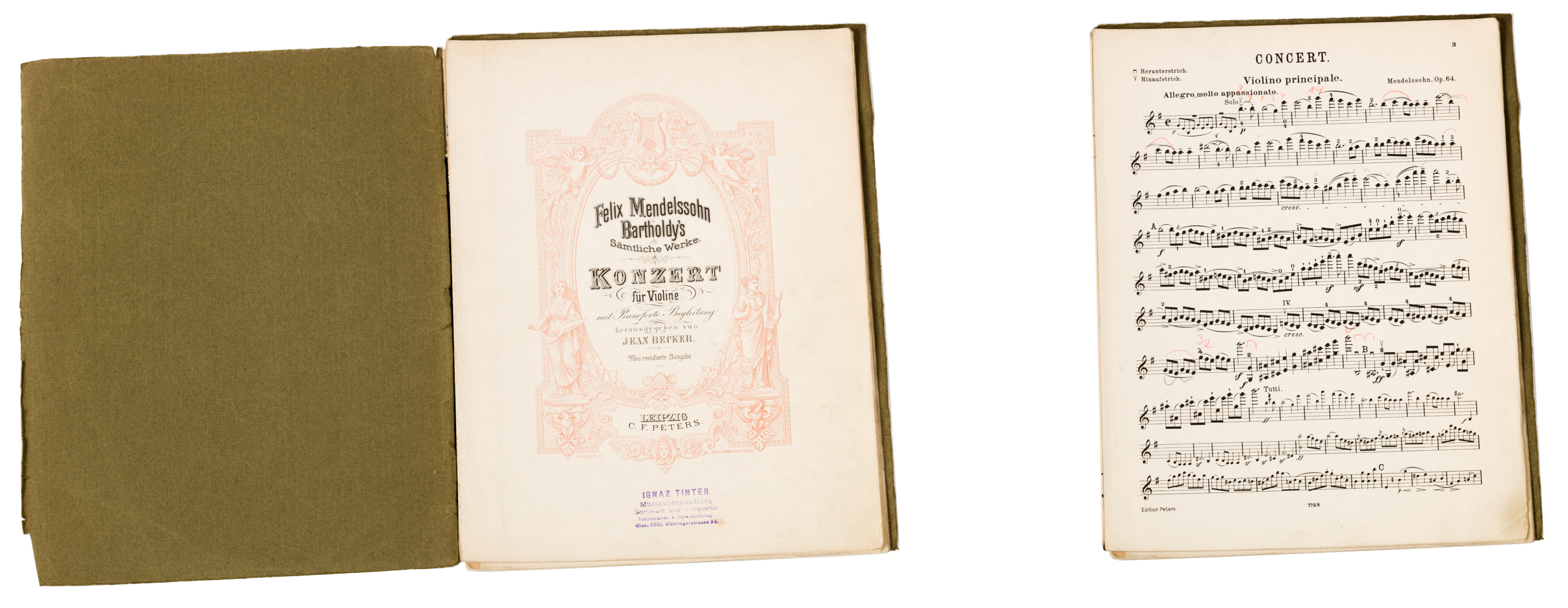

In fall of 1938—a year before the outbreak of the Second World War—a Jewish friend introduced him to “young pianist Hans Kann, who was also Jewish”.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 24 “We got along well, both sight-read well, and systematically devoured our way through a large part of literature for our two instruments,” remembers Cerha. Even then, works by Jewish composers were on the Nazis’ blacklist, including classics such as Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy’s Violin Concerto. Kann’s father owned a copy of the work and one day handed it to Cerha, who played it “passably from sight” and thus secured “the eternal affection” of the music lover. The score would remain in Cerha’s possession thereafter, even if the passage of time later threatened his friendship with the Kanns. With the war already raging, Father Kann walked up to the young violinist, who had just been rehearsing with Hans on the stairs and said: “Fritzl, I think it would be better if you didn’t come back any more. Otherwise, we will all get into trouble.”Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 24

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64, Cerha’s private copy

Photo: Christoph Fuchs

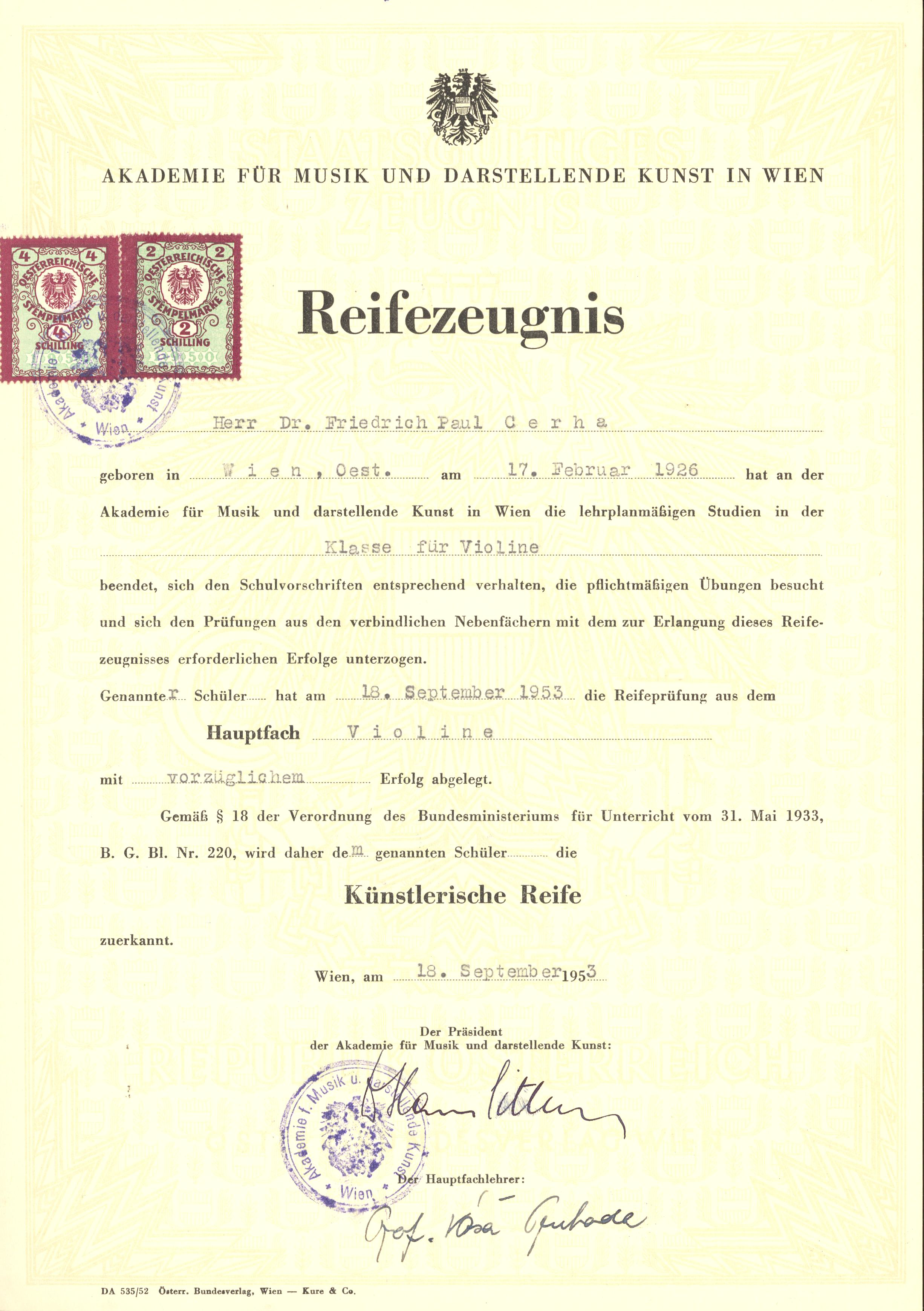

During this time of exploring the city, Cerha was also majoring in violin at the Academy of Music. His two professors, like Anton Pejhovsky, were both Czech: one of them was Gottfried Feist, the “best violin teacher the Academy ever had”.Elisabeth Th. Hilscher and Christian Fastl, “Feist, Gottfried”, in: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online Feist was the first to introduce his pupil to the works of the Vienna School.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 21 Feist’s authoritarian demeanour, however, was also impactful, and accompanied high moral principles: “He would throw students out the door with his own hands, right down the stairs and their violin case after them, if they dared speak of payment in connection with art. His motto was: ‘It is impossible to pay for music. One can, at most, compensate the artist.’” Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 27

Feist was followed by Váša Příhoda, celebrated as a “brilliant virtuoso” since the 1920s (particularly in Austria)Monika Kornberger, “Příhoda, Váša”, in: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online and considered a specialist on Paganini. Shortly after the end of the war, he “was initially no longer hired to play in Vienna, as the Viennese media held him responsible for the death of his first wife […].” However, he recovered quickly and was able to follow up on his earlier successes. Cerha remained “on friendly terms [with Příhoda] until his death”.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 21 The two were still playing together as late as the mid-1950s:

I was passed around in the Viennese home concert scene from early on in my student days, something that significantly expanded my knowledge of music literature. I often played in a string quartet three times a week. It was mainly doctors and lawyers who regularly sponsored string quartets. I generally played first violin, only when my teacher Váša Příhoda or Willi Boskovsky participated did I switch to second. Together with Rafael Kubelik, we played all the major piano chamber music pieces.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 29

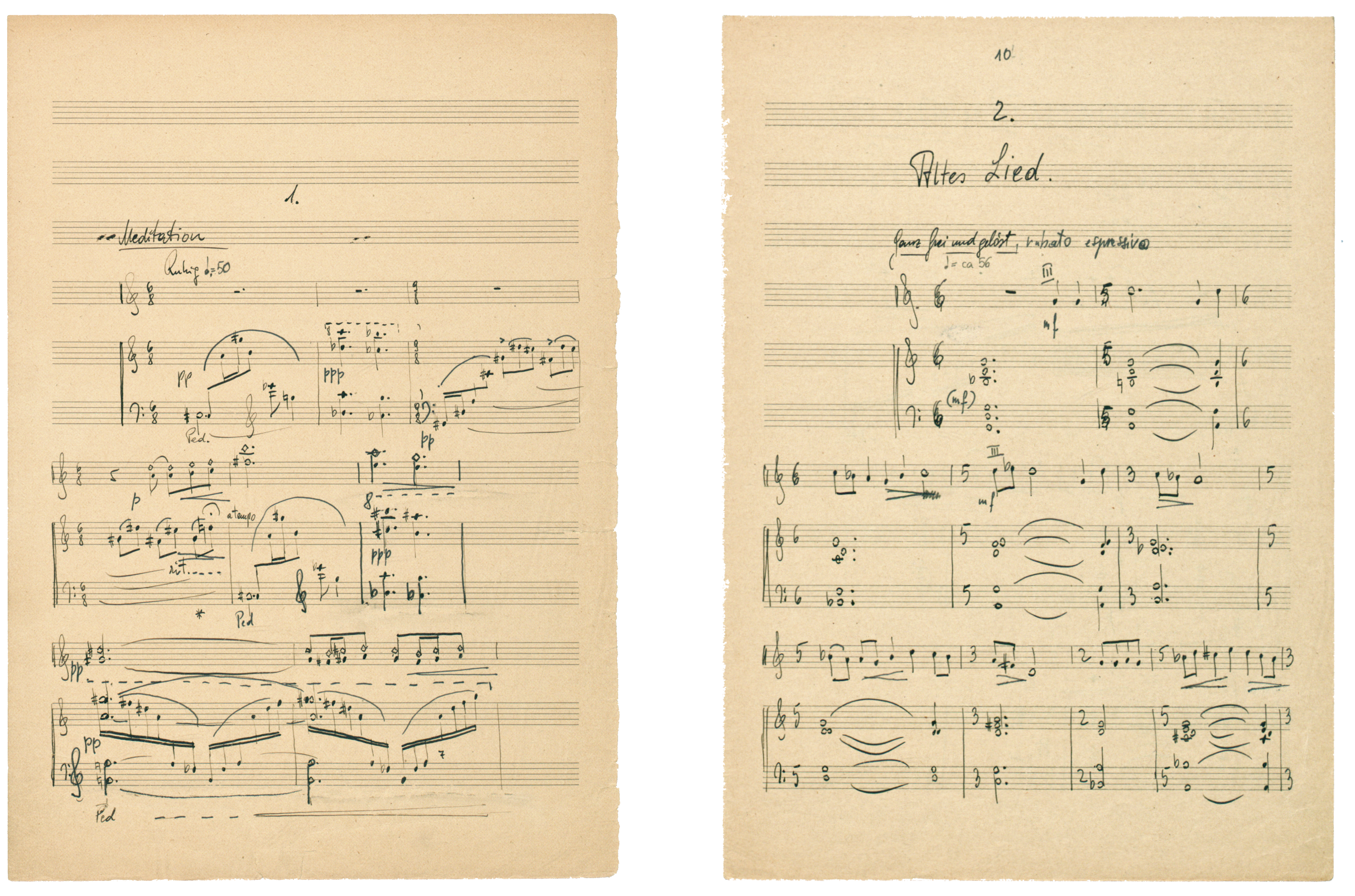

L.: Váša Příhoda with violin, ca. 1921. R.: Cerha, Meditation und Altes Lied, dedication in manuscript, 1951

Left: Thomas A. Edison, Inc./Wikimedia Commons

Right: The Archives of Contemporary Arts, 00000025/37

Cerha, Meditation (Beginn)

Cerha, Altes Lied (Beginn)

Ernst Kovacic (Violine), Mathilde Hoursiangou (Klavier), Produktion Toccata Classics 2013

Cerha graduated in violin and composition in 1953. Even into the 1960s, his commitment to each activity was roughly equal, with each benefitting from the other. As a violinist, Cerha became increasingly involved in the networks of the international avant-garde, focussing on the latest music.

Cerha’s diploma, violin, Academy of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, 1953

Dedicated to the New and Old

When I got out of the war, I was obsessed with an insatiable curiosity for music and devoured tremendous amounts of literature from our century, studying it every day, which brought me to Webern’s violin pieces. At the time, I was inwardly still far from the Vienna School, and was more amazed than fascinated that something like this existed. I initially felt challenged to interpret it musically and asked myself the question: How can one make such music understandable, how—and this is a prerequisite for the first question—can one possibly grasp it oneself, comprehend it? I played the pieces—as I did with much of the music that I wanted to learn about—for Joseph Marx (of all people!). He wasn’t dismissive, but found it “too spicy” and there was “too little meat” in the background for his taste.

Friedrich Cerha

Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Wien 2001, p. 170.

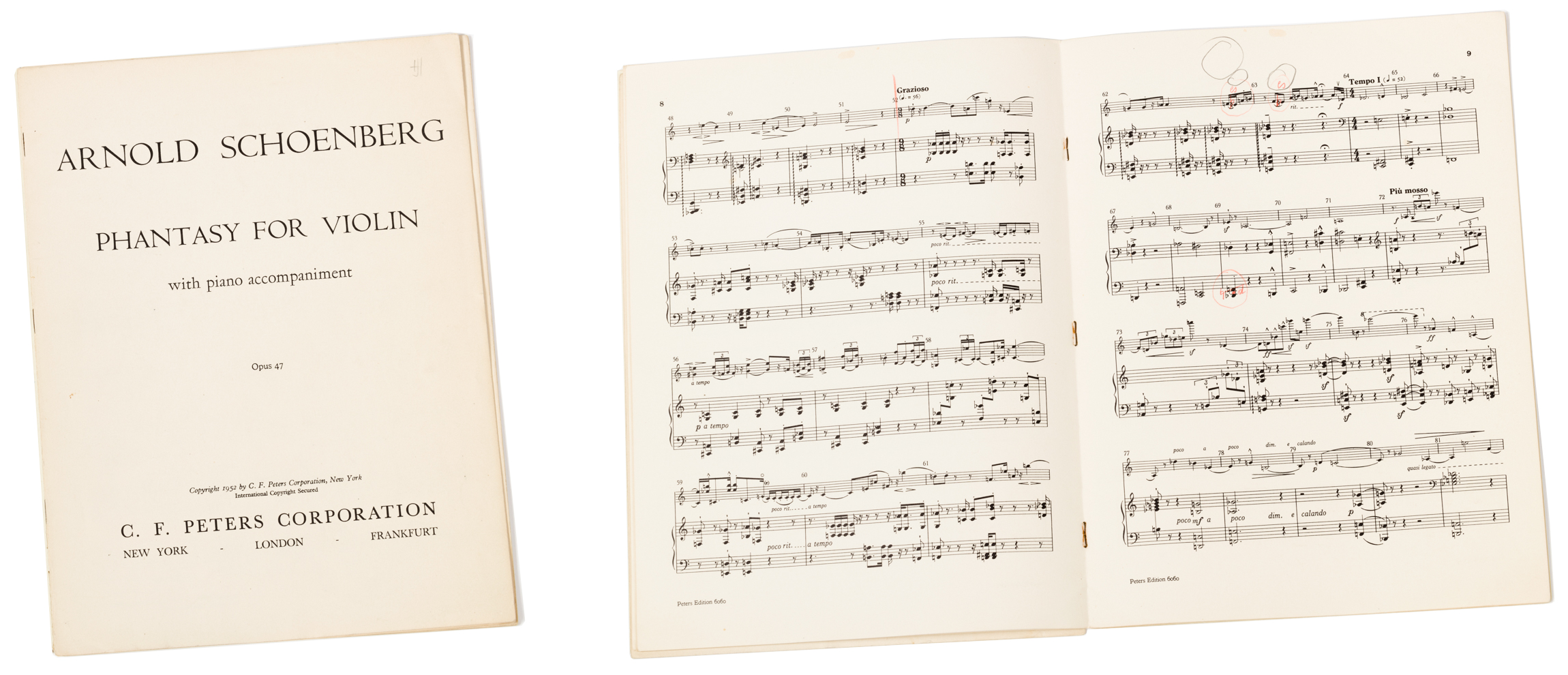

Cerha devoted himself with increasing zeal to the musical legacy of the Vienna School. On the tenth anniversary of Webern’s death (1955), the IGNM (International Society for New Music) held a memorial concert in the Schubert Hall of the Wiener Konzerthaus. Cerha played “all violin parts” under the baton of Michael Gielen.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 170 Equally memorable: a public workshop during the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. Hanns Jelinek, a student of both Schönberg and Berg who had only recently become a lecturer at the Vienna Academy of Music, taught pieces by the Vienna School at the Austrian Pavilion and brought Cerha in to join him as a violinist. There, he played “Schönberg’s Phantasie für Violine und Klavier Op. 47, Webern’s Vier Stücke für Violine und Klavier Op. 7 and Bagatellen Op. 9, and Jelinek’s very difficult 1956 solo sonata.”Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 31 Jelinek’s approach of “accurately deriving the consequences of technical performance by analysing the pieces” fascinated Cerha and contributed to the deepening of his musical understanding as an interpreter and composer.

Friedrich Cerha and Hanns Jelinek, Brussels World Exhibition, Austria Pavilion, 1958

Arnold Schönberg, Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment, Op. 47, Cerha’s private copy

Schönberg, Phantasy, Op. 47, Friedrich Cerha (violin), Ivan Eröd (piano)

Performance date unknown.

AdZ, CER-S1-97T-26/29/47/50

In addition to works of the Vienna School, Cerha also frequently performed pieces by his friends and fellow composers. Even while still at the music academy he played in the composition classes of various teachers, from Joseph Marx to Karl Schiske to Otto Siegl, performing new violin pieces by his associates—of course Hans Kann and Paul Kont, but Gerhard Lampersberg, Kurt Schwertsik, and Anestis Logothetis as well. Cerha was the first to arrange Logothetis’s piece Integration (1956), a trio for violin, violoncello, and guitar, which Logothetis had written using conventional notation before later turning to a graphic notation system (the interpretation of which was a subsequent focus of Cerha as a conductor).

Around the same time, the Darmstadt Summer Courses for New Music were also challenging Cerha as a musician. When participating in the courses, in 1956 he performed new violin music from America; together with David Tudor, John Cage’s “house pianist”, he performed a piece by Richard Maxfield, a pioneer of electronic music, for the first time.

In Darmstadt, Cerha made contact with other composers, for whom he often played as a violinist. Italian Sylvano Bussotti, a proponent of graphic notation, dedicated a piece to him, Sensitivo (1959), for “a solo string instrument”, of which Cerha performed the world premiere. He also made periodic appearances on violin as part of the ensemble activity of “die reihe”. In 1959, for example, at their third concert, he played Morton Feldman’s Extensions 1, once again in duet with Tudor.

Sylvano Bussotti, Sensitivo, detail from Cerha’s copy with handwritten entries

The ensemble played vocal and instrumental music in various instrumentations “with regularity for four years in the beautiful ambience of the Belvedere Palace”.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 29 Unfortunately, most documentation of Cerha’s phase as an interpreter of early music has been lost.See Sabine Töfferl, Friedrich Cerha: Doyen der österreichischen Musik der Gegenwart, Vienna 2017, p. 131 However, the ORF documentary Zu Gast bei Friedrich Cerha (1975) does provide some insight, as well as recordings of the violinist at his residence in Vienna. He is accompanied—naturally—by Gertraud Cerha on her home harpsichord.

Zu Gast bei Friedrich Cerha, documentary, ORF 1975

Cerha’s interest in old instruments is multifaceted, with a focus on honing his instrumental skills, bearing compositional fruit, and broadening his musical horizons. He has also been interested in questions regarding how instruments were made and the playing conditions of the time. His drawings of historic bows for “high string instruments”, part of the Vienna Art History Museum’s collection of old musical instruments, are quite informative in this regard. With an almost scientific curiosity, Cerha investigates the constructive details through drawing and comparing proportions, materials, shapes, and specialties. The result is a study testifying to his love for the violin in another medium.

Cerha, drawings of old bows for high string instruments, undated, AdZ, SCHR0009/3

Playing Music, Creating Music—Two Sides of the Same Coin

The violin is also responsible for launching Cerha’s career as a composer. The oldest piece still in existence today, a duet for two violins, dates from 1935. This means that Cerha composed it at the age of nine—probably playing it in lessons with his teacher Anton Pejhovsky. Two sonatas for solo violin followed in 1937, though the manuscripts did not survive: The first was lost, the second later destroyed, a fate that befell many of his early works.

Cerha, duet for two violins, folder and first page of the score, 1935, AdZ, 00000001

Cerha, Sonatas for Violin and Piano 1–3, title pages of the manuscripts (excerpts), 1946–1955

Cerha performed the premieres himself. He presented Deux éclats for the first time as part of the ICNM Vienna, and performed Formation and solution for an audience at the Darmstadt Summer Courses in 1958. In addition to their structure, the experimental sound of both pieces was impressive. In particular, Deux éclats en reflection is littered with “unusual ways of playing” that produce “bizarre sounds”, creating music that is “uniquely unpredictable”.Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 221

Cerha, Deux éclats en reflexion, instructions for the violin, 1957, AdZ, 00000047/4

Violin: Friedrich Cerha, piano: Ivan Eröd, performance date unknown.

AdZ, CER-S1-97T-26/29/47/50

Cerha, Concerto for violin and orchestra, II. Nachtstück (1st section)

RSO Wien, Ltg. Bertrand de Billy, Ernst Kovacic (Violine), Produktion col legno 2006