Piccola commedia

Theatre on the Fly

Konzert für Violine, Violoncello und Orchester

Klavierstücke für Kinder oder solche, die es werden wollen

Commedia dell’arte style masks

In the Italian commedia dell’arte, masks were a standard part of the costume. They made the characters into people and showed their social groups. Over time, the masks became more stylised—symbolising, for example, Harlequin (a hand puppet), Colombina (a seductive maid), or Pantalone (a shady merchant).

Source: Dagoos/Wikimedia

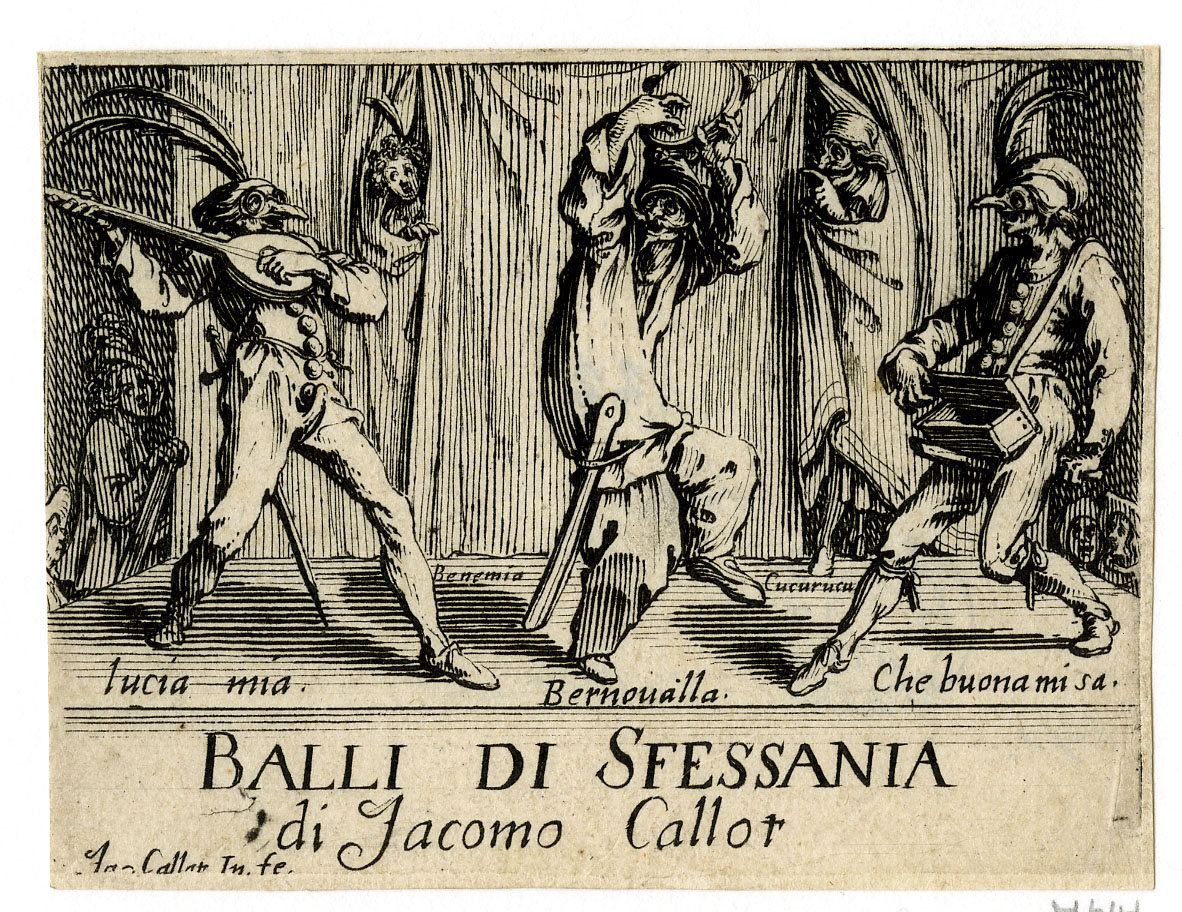

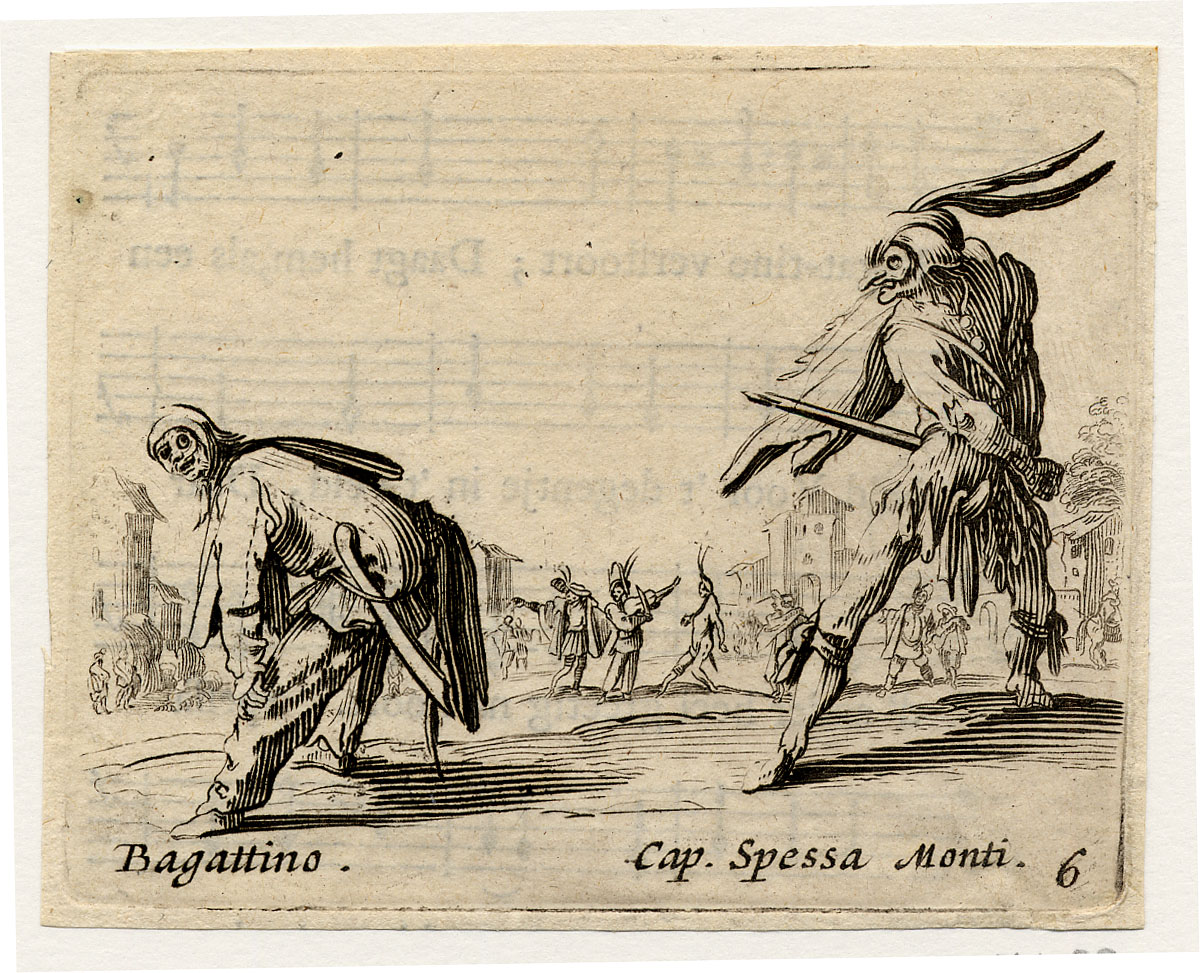

In around 1620, an artist from Lorraine set out for Italy,

soon recording his impressions in copper engravings that are a testimony of the theatrical spirit of the time.

The creator of these impressive engravings, held in great esteem by Cerha, is Jacques Callot. His series of 16 motifs, titled Balli di Sfessania, shows the theatre dances of the same name, which attracted throngs of audiences in Italy at the time. These dances were performed by the actors of the Commedia dell’arte, a folk theatre that originated in Venice and Naples and flourished in Europe from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. Its primary characteristics: The focus was not on individuals and their emotional worlds, but on stylised “types” with often grotesque masks. In Callot’s engravings, the characters often face each other in a duel, just as the charm of the Commedia came from human contrasts, for example between the “Zanni” (the commoners) and the “Vecchi” (the rich elite). At the age of 88, Commedia dell’arte inspired Cerha to compose a whimsical, entertaining play, the Piccola commedia.

Außenansicht

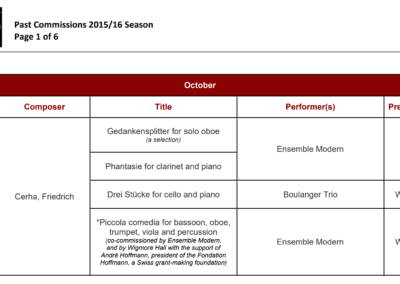

Ferruccio Busoni, orchestral suite for Gozzi’s Turandot, cover of the score, Breitkopf and Härtel, 1906

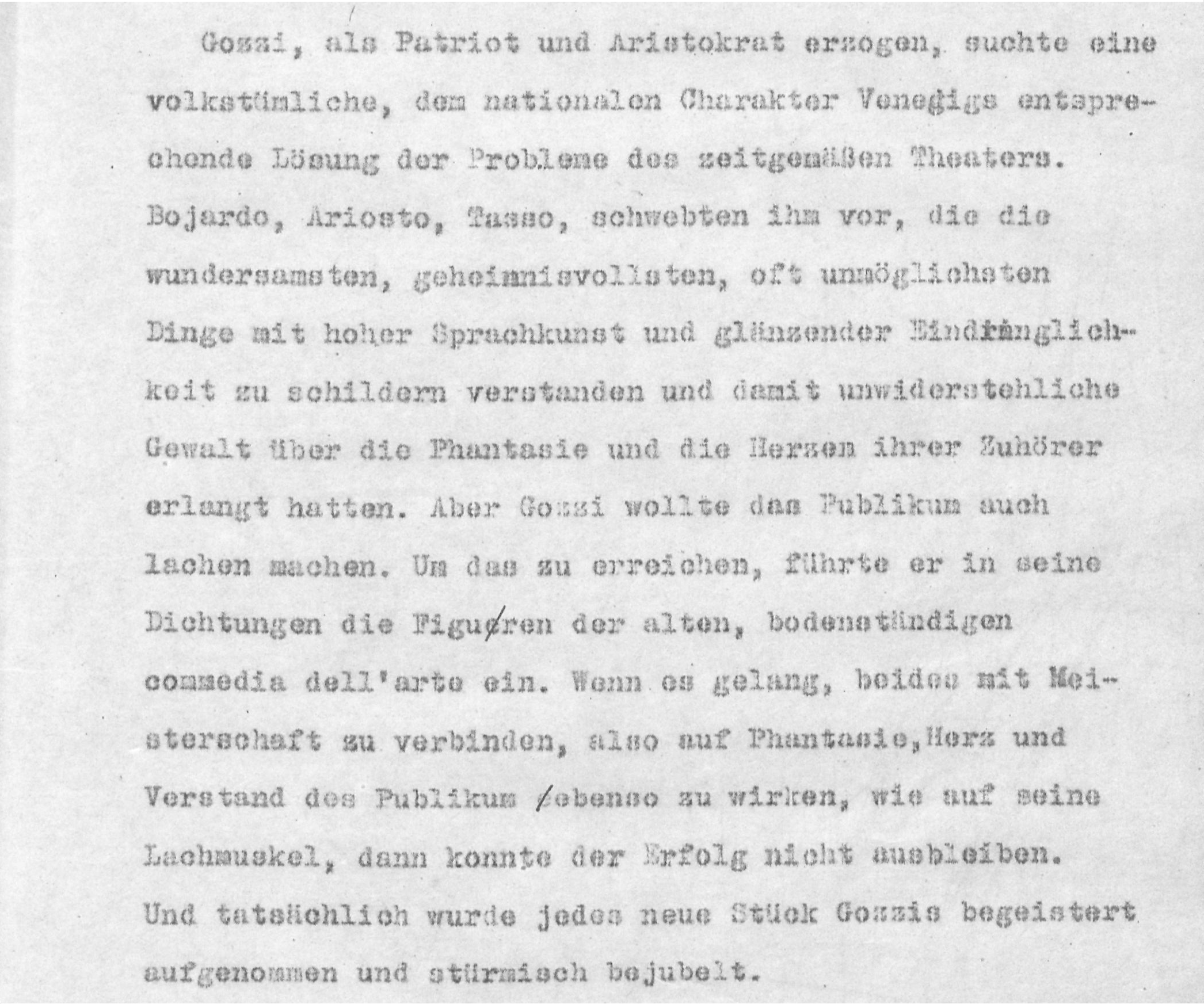

The connecting lines in Cerha’s oeuvre occasionally stretch far. In some places, aspects of earlier creative periods reappear to unexpectedly set new impulses—as is the case of the 2014 work Piccola commedia. Around this time, the plays of Carlo Gozzi, one of the great Italian dramatists of the eighteenth century, fell into Cerha’s hands. Gozzi’s specialty was fairy tale dramas (“fiabe teatrali”). Starting with Die Liebe zu den drei Orangen (1761), he tailored nine other fantastic stories for the stage within just a few short years, some of them later becoming operatic material: Richard Wagner used Gozzi’s La donna serpente for his debut piece Die Feen, for example, and Hans Werner Henze for König Hirsch in the 1950s. By far the most well-known fairy tale transformed into an opera is Turandot. Not only did Ferruccio Busoni put music to Gozzi’s theatre piece—Giacomo Puccini did the same, creating a repertoire piece with no equal for all posterity. Cerha dealt with both operas very early on, more precisely: In the late 1940s, when he was writing his doctoral thesis on “Turandot in German literature”. He even wrote a whole subchapter on Gozzi’s Turandot. There, he positions the poet in the Italian theatre landscape, connecting him to Commedia dell’arte, which Gozzi defended against efforts to modernise it in Venice at the time.

Cerha, Der Turandotstoff in der deutschen Literatur, II.2 “Carlo Gozzi’s Turandot”, p. 95

Between the time of Cerha’s dissertation and the years in which he wrote the Piccola commedia more than 60 years passed. However, Gozzi’s pieces did not lose their hypnotic spell on him during this time, quite the contrary: When Cerha re-read two of them (Turandot and The Raven) “with pleasure”, he remembered “the fascination that the commedia dell’arte had always held for [him].“Joachim Diederichs: Friedrich Cerha. Werkeinführungen, Quellen, Dokumente, Vienna 2018, p. 137 The reading experience was (as in many other cases) not without consequence, triggering a cascade of sound fantasies: A music matured in his head that followed his instinct for theatrical play.

Brücke

“The second time I broke out was in 2013/14,” the composer goes on to recall. “Suddenly, unplanned and unforeseen, the music for an imaginary comedy for five virtuoso players bubbled up”—and thus Piccola commedia was born. However, this surprising appearance must be classified differently than that of Keintate and Chansons. These two cases were based on writings that inspired the light-heartedness, countering the weighty operas being written at the same time (namely Baal und Der Rattenfänger) with a smile. The compositional examination of Viennese folk music was a different kind of reaction. Cerha’s preoccupation with non-European musical cultures had persuaded him to take a close look at the musical culture of his own country, both breaking it down and celebrating it at once.

Piccola commedia is also the result of a dialectical creative process in which one thing unleashes something completely opposite. In fact, the quintet seems to be a reaction to two massive orchestral pieces that were written immediately prior: Nacht (2011/2013) and Eine blassblaue Vision (2013/2014) are fully in the Cerha-specific tradition of sound composition. Seen this way, the desired contrast is also in opposition to an exclusive concept of music shaped by avant-garde ideas.

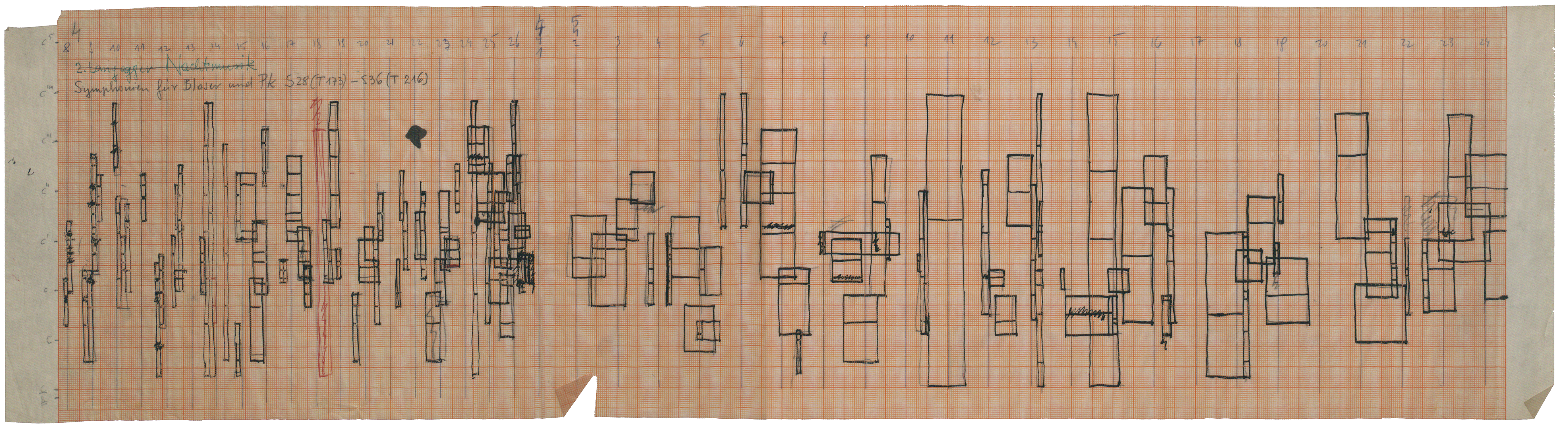

Similar reactions from Cerha can be observed much earlier. While working with mass structures was at the centre of his compositional activities around 1960, the pendulum swung in a different direction somewhat later. A new ideal emerged: “Clarté”—polished instead of blurred contours, transparency instead of concealment. He realised this idea for the first time in Symphonien für Bläser und Pauken (1964): Blocky, lacking fine transitions, the music literally chisels itself out. Looking at the graphic sketches, one sees Cerha’s statement almost sculpturally, “driven by a restlessness”, “not letting the fine design of a room make you forget how entire cities are built.“Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 237 Nevertheless, the Symphonien are, similar to several other of Cerha’s compositions, written in an orchestral style. Piccola commedia takes, much later, an entirely different path, yet does not give up on the ideal of “Clarté”.

After the turn of the millennium, the joy of playing itself increasingly led Cerha to compose new works. Numerous instrumental concerts were created in quick succession, celebrating virtuoso music-making in their own way (and yet were not mere ends in themself). On the other hand, chamber music was also experiencing new impetus. A desire for musical “conversation” was being realised in duos, trios, and quartets. The architecture of the sound took a back seat here. The focus was rather on “the experience of joyfully pushing forward the playing of music”, which Cerha saw as having “fallen into disrepair” since the 1950s.Joachim Diederichs: Friedrich Cerha. Werkeinführungen, Quellen, Dokumente, Vienna 2018, p. 129 This recapturing of lightness, symbolised by Piccola commedia, goes back not least to the fundamental experiences that accompanied the composer as a practicing musician (above all as a violinist) throughout his life.

Innenansicht

Note

Unfortunately, the Archive of Contemporary Arts to this day does not have a recording of Piccola commedia. “Cerha Online” therefore makes a call to all interested performers and programme planners to bring the work to the concert stage. If you want to offer us a recording, please contact: cerha-online@donau-uni.ac.at.

The story of Piccola commedia takes us to London. It was premiered at Wigmore Hall, one of the world’s acoustically finest concert halls for small ensembles. “Friedrich Cerha Day” was proclaimed here on 10 October 2015, with the support of the Austrian Embassy. In honour of the composer’s approaching 90th birthday, a cross-section of his chamber music was presented in two concerts, played by the Ensemble Modern. A look at the programme encourages the connection of Piccola commedia to a much earlier work: the Konzertanten Tafelmusik from 1947/48. The similarities in line-up are striking: In Tafelmusik, four winds (oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and trumpet); in Commedia, five instruments (oboe, bassoon, trumpet, percussion, and viola). The extensive and substantial branching of Cerha’s oeuvre suggest that this superficial parallel is not the only thing to be taken into consideration—an assumption confirmed by the composer’s commentary on the piece. “As in commedia dell’arte, numerous references are made: Satie, Schubert, my own 1980s work Chansons. Yes, there are even associations with 1947/48’s—more than sixty years ago—Tafelmusik.“Joachim Diederichs: Friedrich Cerha. Werkeinführungen, Quellen, Dokumente, Vienna 2018, p. 137

And Piccola commedia intertwines even more: It is not only a vessel for pre-existing music, but a nucleus for later music as well. Like “echoes”, two offshoots were created “based upon the material” in 2014: Bagatelle combines elements of Commedia and of Vorspiel zu einer Komödie “like a potpourri. Joachim Diederichs: Friedrich Cerha. Werkeinführungen, Quellen, Dokumente, Vienna 2018, p. 137 Both pieces expand the music of the quintet into an orchestra, also emphasising the importance of Piccola commedia in the composer’s late work.

Cerha, Bagatelle für Orchester, sketch, 2014, AdZ, 000S0186/1

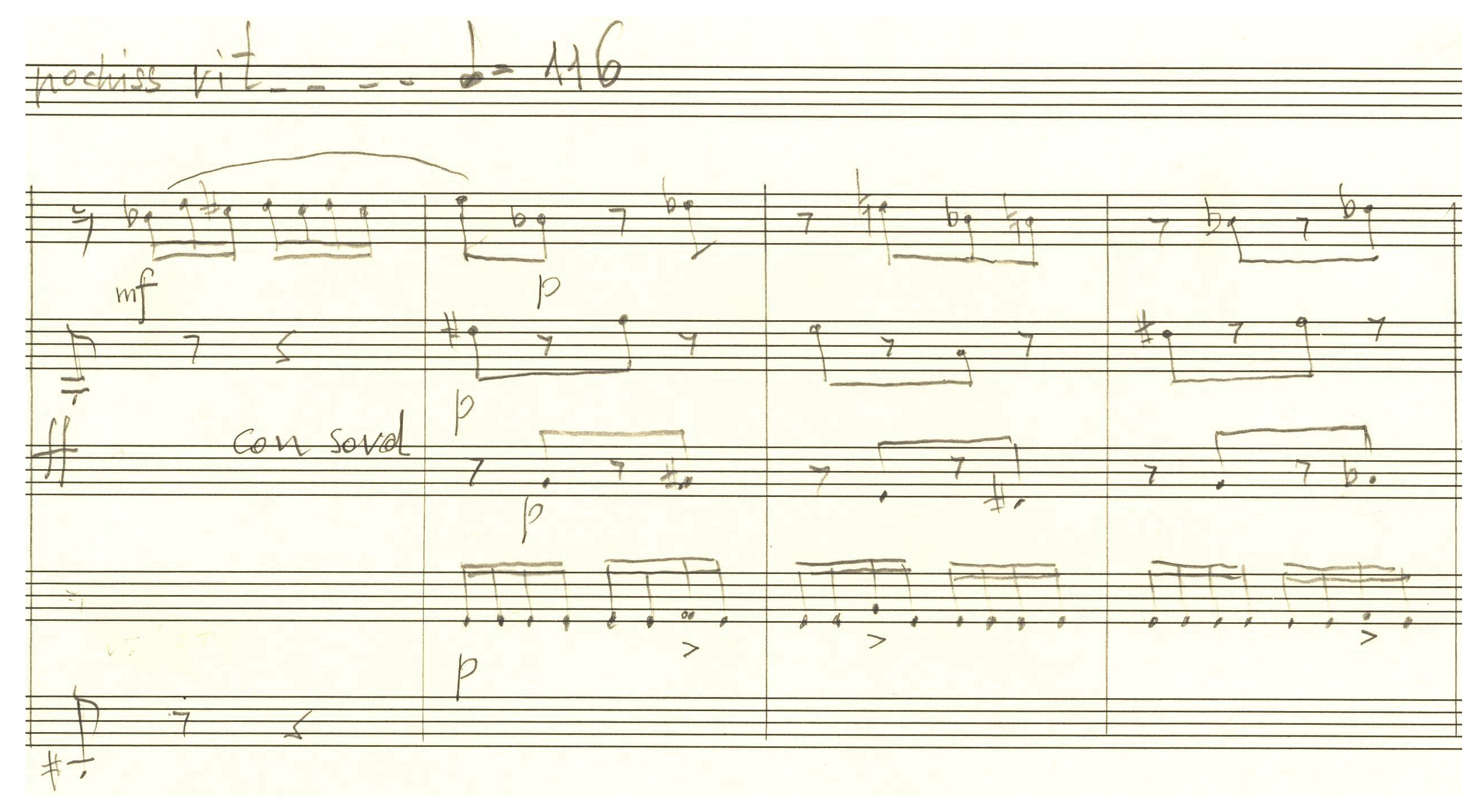

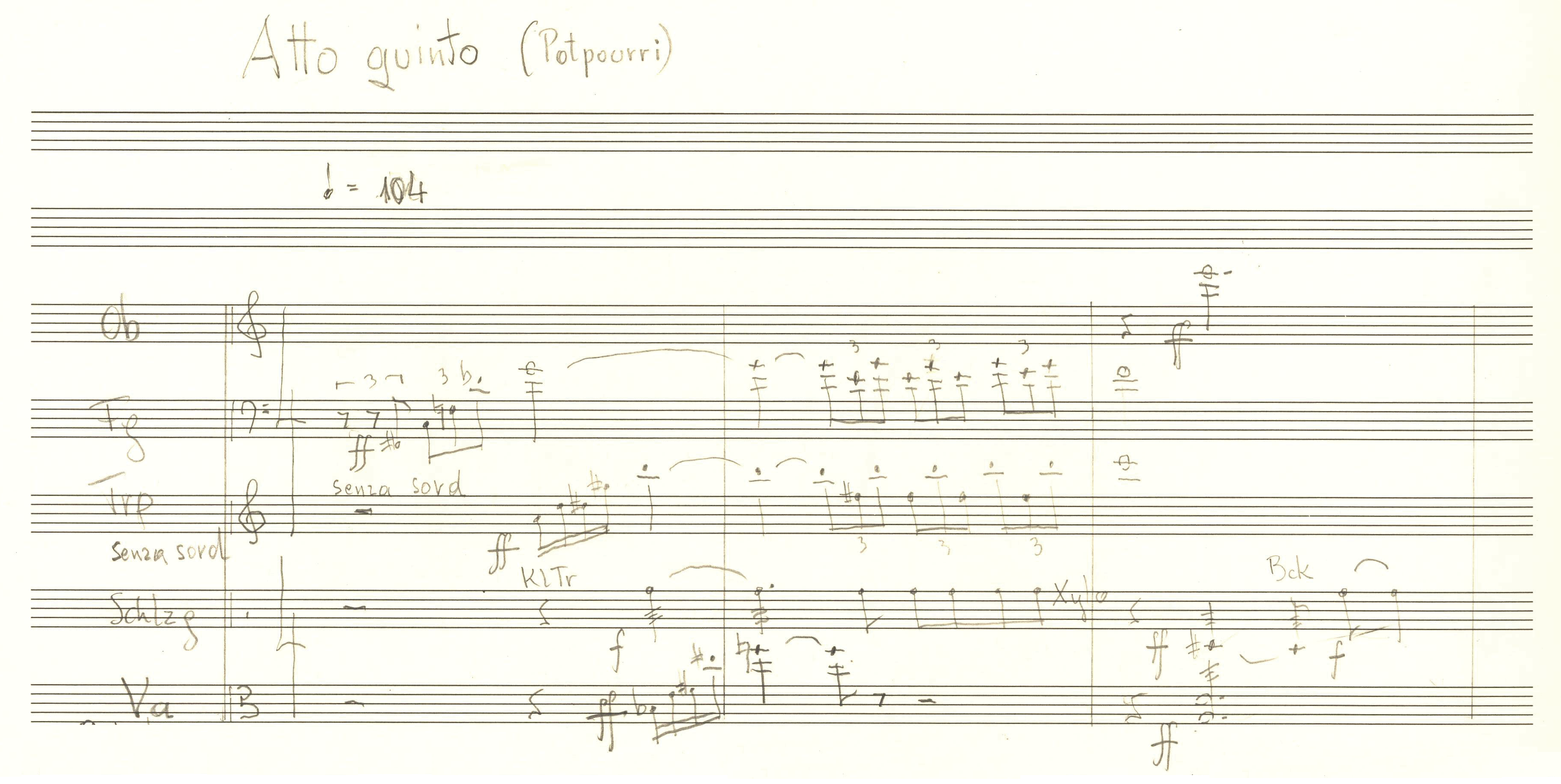

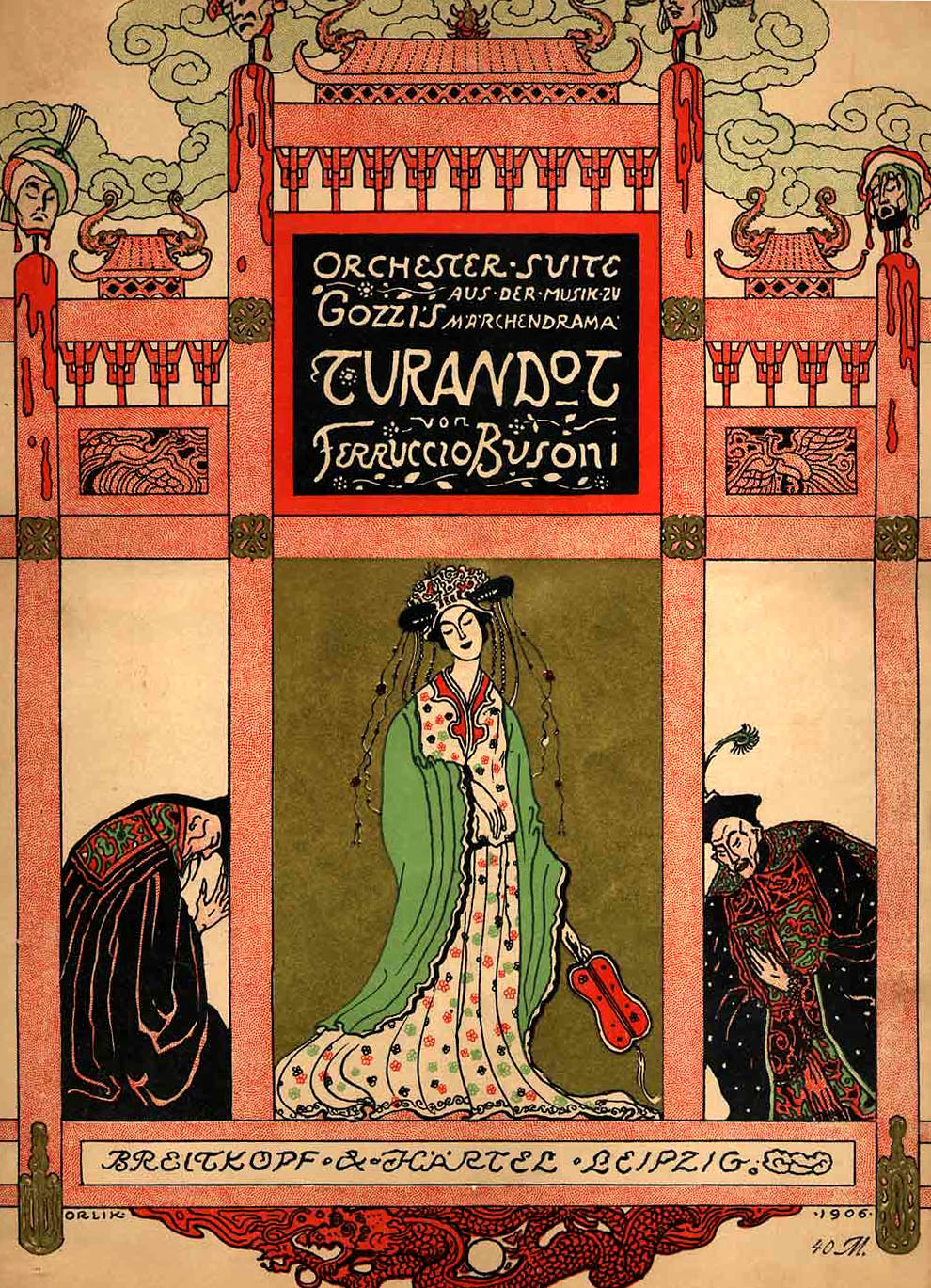

These two side pieces already emphasise aspects of the dramaturgy: Vorspiel zu einer Komödie flirts with the same overture that also opens Piccola commedia. Bagatelle, on the other hand, is connected to the final movement, which Cerha even names “Potpourri”. The composition mimics the overall structure of a play. After the overture, there are five acts plus “a rollicking intermezzo between the third and fourth acts.“Joachim Diederichs: Friedrich Cerha. Werkeinführungen, Quellen, Dokumente, Vienna 2018, p. 137 This structure is based on the classic dramatic construction that has dominated since the seventeenth century. The comedic poets of Roman antiquity (particularly Plautus and Terence) also consistently followed the five-act scheme. Cerha’s inspirational templates—Gozzi’s Turandot and Der Rabe—are also five acts long. The insertion of an intermezzo, on the other hand, is remarkable. In commedia dell’arte, musical interludes were quite common and was not unusual for songs to be sung or for dancing to take place between acts. However, such a clear intermission function is not given in the Piccola commedia, which has a musical number within a piece of music. The relationships to the piece as a whole are more the focus: As there is no set and no text, it is up to the listeners themselves to search out any narrative threads.

Cerha, Piccola commedia, handwritten score, movements and instrumentation, 2014

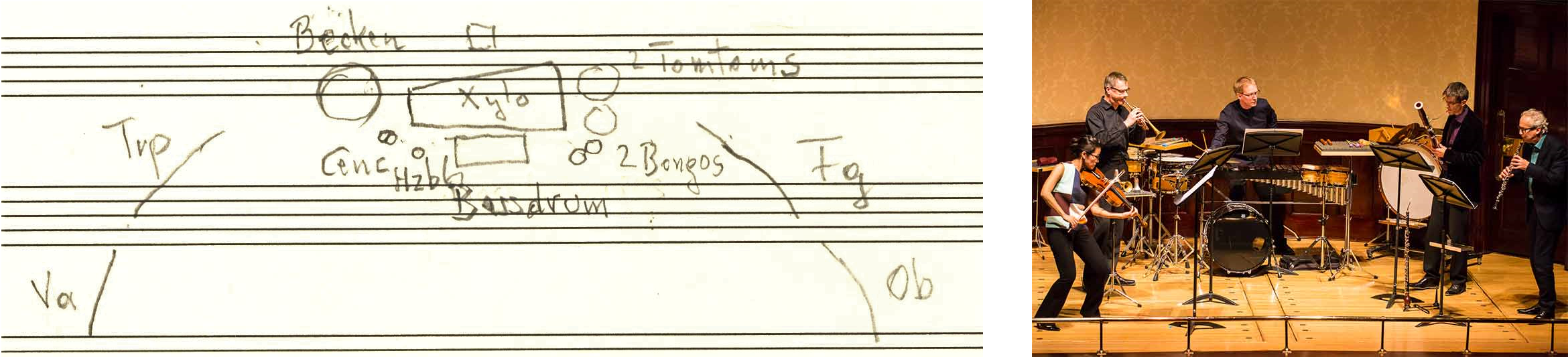

Piccola commedia, installation sketch (l.) and photo of the premiere (r.)

The fact that Piccola commedia was inspired by Commedia dell’arte can be seen not only in its outward structure, but also in the inner dramaturgy. “Music, virtuosic, enjoyable, cheeky, full of surprises—a circus,“Joachim Diederichs: Friedrich Cerha. Werkeinführungen, Quellen, Dokumente, Vienna 2018, p. 137 summarises the composer, “Only the third act is for pausing, contemplating, and reflecting.” While the Italian theatre style did attempt to depict tragedy, it was primarily the comedy of life that was brought to the stage. The themes are timeless, found in the interweaving of lust for life, intrigues, courtship, and slapstick. They primarily found “their intellectual breeding ground in the world of carnival”, historically anchored in the flourishing humanism of the Renaissance era, “which rebelled against […] the rule of the church and its ascetic turning away from life.“Ingrid Ramm-Bonwitt, Die komische Tragödie, Vol. 1: Commedia dell’arte, Frankfurt a.M. 1997, p. 18 Entertainment is at the core of Italian folk theatre, while its relationship to art remains ambivalent: The commedia dell’arte “is in its own self-contained world, where a free theatre unfolds that is based upon conventions, but also on strong stylisations, working in an almost musical manner with variations of well-known plot schemes and scenes.“Wolfram Krömer, Die italienische Commedia dell’arte, Darmstadt 1976, p. 28

This characteristic theatrical structure is also important for Cerha. Sound gestures appear throughout Piccola commedia, their expressive quality based on traditional musical symbolism. The overture begins with fanfare in the trumpet—the imaginary curtain draws open. Motoric movements follow—characterising the entire piece and conveying the physicality of the overall sound, which remains in the foreground. Percussive gestures drive the music forward again and again. Characteristic: A temporary pulsing in the drums. In the overture, there is a pounding and powerful pulsation on a bass drum (with pedal) and two tom-toms. In the third movement, the only quiet one, it returns as a soft xylophone sound, now “dull” and “bell-like“Cerha, Piccola commedia, handwritten score, AdZ, 00000185/41 in a cantabile environment.

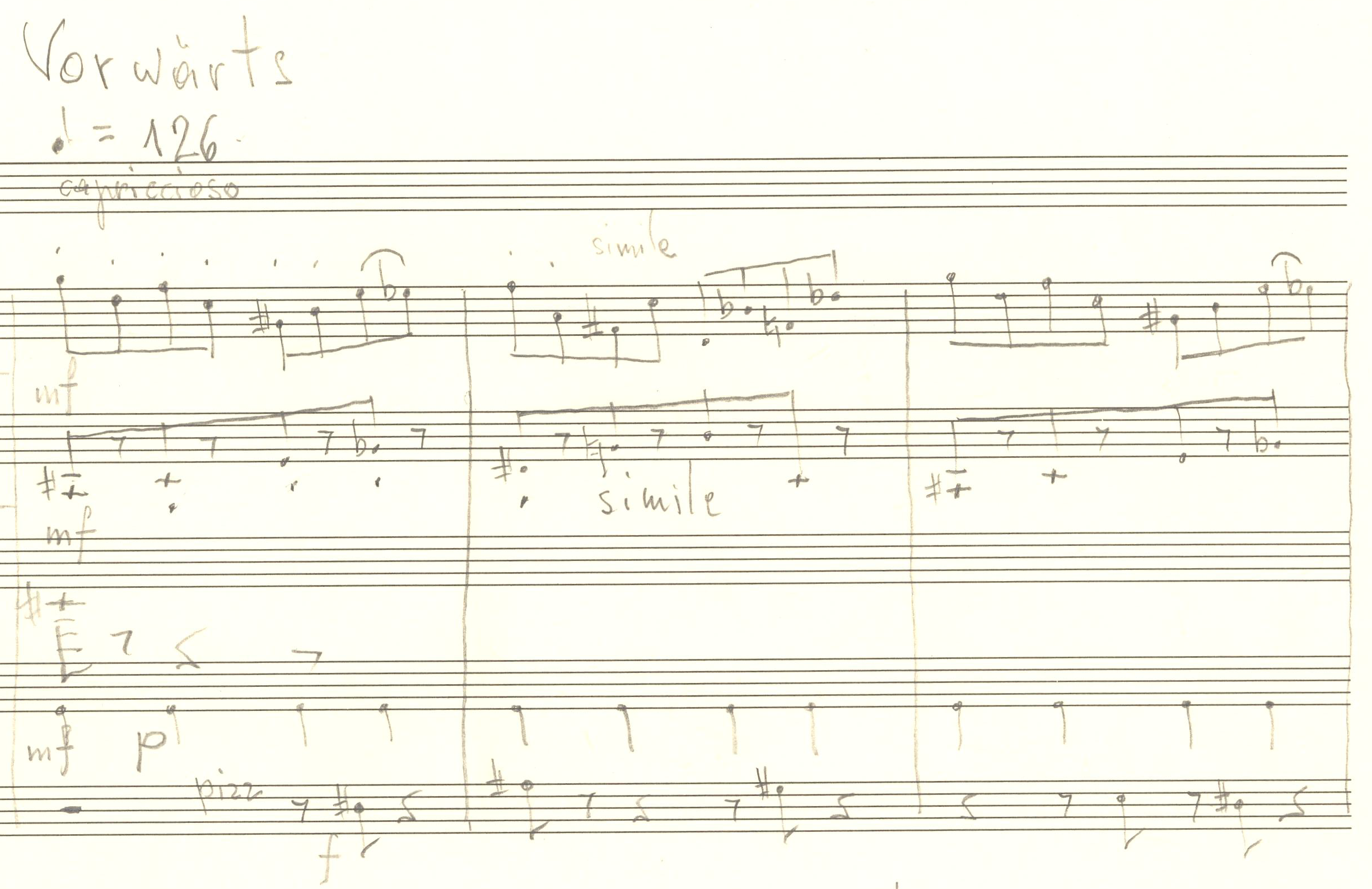

Cerha, Piccola commedia, handwritten score, overture, mm. 1–6, 2014

A certain temperament is almost typical of Piccola commedia. Changes in tempo and (sometimes sassy) interjections shape almost all the movements. The musical flow tends not to be uninterrupted and without barriers, but is instead repeatedly steered to another path for a short time by a side note, either staying there or returning. In this way, the musical development remains unpredictable, its moments always fresh. The resulting game of expectations is also a game of musical skill. Rhythmic emphasis and linear movements create two maxims. It is not by coincidence that these were also compositional ideals in the neoclassicism of the 1920s. Piccola commedia consciously flirts with the stylistic sense of that era, the “distant musical attitude“Schriften: ein Netzwerk, Vienna 2001, p. 217 of Stravinsky or Hindemith. The reason for the piece’s proximity to the matter-of-fact, entertaining idiom of the “Golden Twenties” is also rooted in its prior influence from Konzertante Tafelmusik. At the time, Cerha had been particularly interested in the neoclassical style, after all, it was the only modernist trend of post-war Vienna. The unique types of movement and rhythmic interlocking of Piccola commedia, evoke this early phase of Cerha’s work from a later perspective.

Cerha, Konzertante Tafelmusik, manuscript (early version), 1953, AdZ, 00000016/3

Cerha, Piccola commedia, handwritten score, overture, mm. 51–53, 2014

Cerha, Divertimento, Movement 1, beginning

Note: Divertimento is a later arrangement of Konzertante Tafelmusik.

Radio Symphonie Orchester Wien, Ltg. Friedrich Cerha, ORF Edition Zeitton 2001

Elsewhere, solo elements are exposed, revealing motor elements—Cerha gives the players numerous opportunities to briefly come to the fore. A striking example: In the intermezzo, the xylophone detaches itself from the overall ensemble with virtuosic runs. Its characteristic figure spirals around a central note that is struck again and again at a rapid tempo. Other sharply accentuated tones emerge from this chain from time to time. Dizzying runs then lead to further sequences of other central tones—requiring highly precise work from all performers. These musically acrobatic interludes are similar to the occasional artistic intermezzi of the Commedia dell’arte. Any possible form of expression could be included in the game—physical theatre dominated the stage.

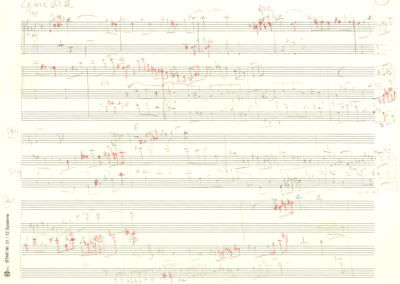

Wooden xylophone garlands are also a central part of Bagatelle für Orchester, which is based upon Piccola commedia. Running throughout the short piece, they are its most important guiding element. Cerha also uses this figure in Konzert für Schlagzeug und Orchester , written in 2007. There, it is staged in the virtuosic finale with equally expansive means.

Cerha, Piccola commedia, handwritten score, “Intermezzo”, mm. 26–29, AdZ, 00000185/48

Cerha, Bagatelle für Orchester, handwritten score, mm. 9 f., AdZ, 00000186/4

Cerha, Bagatelle für Orchester, xylophone passage

Bamberger Symphoniker, Jonathan Nott

(Recording of the world premiere)

With kind permission of BRKlassik

The numerous colourfully passing moments in the Piccola commedia lead to the “potpourri” of the last “act”. Characteristic episodes reappear from our memories and are melted together into a new piece. This flirtation with entertainment music goes far back into Cerha’s childhood. Potpourris, or medley, were a popular form of the early radio music that he was listening to in the 1930s. In order to appeal to a broader audience, it was customary to string well-known melodies from operas and operettas together, connecting them with transitions—often with a more or less deliberately parodying tone.

In Cerha’s own oeuvre, a potpourri completes the work Serenade, written in 2006. There, atmospheric images of the three previous movements alternate vivaciously, a “turbulent game with a variety of contrasting elements and memories.“Cerha, commentary on Serenade, AdZ, 000T0146/2 However, the process results in more than a mere stringing together. Fine transitions and emerging connections, stimulated by a prominent mandolin, tie the music together.

Cerha, Serenade, Potpourri IV (beginning)

Ensemble „die reihe“, Friedrich Cerha, Wiener Konzerthaus, 2009

Like the potpourri of Serenade, the one in Piccola commedia is also filled with drama. The amusing capers of the music convey a string of surprises. Sudden increases in speed on the one hand, accelerations that peter out on the other. Moments from the previous movements are cleverly inserted to create a miniature-like theatrical finale with many twists and turns. Here, there is room for the fanfares and drumbeats of the overture, short “singing” interludes, hopping sound shapes, and artistic cascades of notes. Even the xylophone is brought back into the limelight, reviewing its bravura piece once again. Cerha’s juggling of these diverse musical moments is characterised by a virtuoso improvisation with well-known elements. In Commedia dell’arte as well—famous not only for its improvisational aspects—free play was of great importance: The actors acted without a script, following a roughly outlined plot. Only the logic of the characters they embodied limited their scope.

Cerha, Piccola commedia, handwritten score, Potpourri, mm. 1–3, AdZ, 00000185/69

The music of Piccola commedia is free music in the best of ways—not only because of its improvisational playfulness, but also because of the informal approach behind it. According to Cerha, while composing, it was clear to him that any “recourse” to more traditional gestures “violated the currently prevailing aesthetic ‘rules’”.Joachim Diederichs: Friedrich Cerha. Werkeinführungen, Quellen, Dokumente, Vienna 2018, p. 137 And so he paid them little attention. “At the time, I drove the avant-garde development forward, but never bothered with a doctrine and never turned ideas into dogmas. And I really enjoyed writing the piece.”